Abstract

Background

Numerous medications are available for the acute treatment of migraine in adults, and some have now been approved for use in children and adolescents in the ambulatory setting. A systematic review of acute treatment of migraine medication trials in children and adolescents will help clinicians make evidence‐informed management choices.

Objectives

To assess the effects of pharmacological interventions by any route of administration versus placebo for migraine in children and adolescents 17 years of age or less. For the purposes of this review, children were defined as under 12 years of age and adolescents 12 to 17 years of age.

Search methods

We searched seven bibliographic databases and four clinical trial registers as well as gray literature for studies through February 2016.

Selection criteria

We included prospective randomized controlled clinical trials of children and adolescents with migraine, comparing acute symptom relieving migraine medications with placebo in the ambulatory setting.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers screened titles and abstracts and reviewed the full text of potentially eligible studies. Two independent reviewers extracted data for studies meeting inclusion criteria. We calculated the risk ratios (RRs) and number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) for dichotomous data. We calculated the risk difference (RD) and number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) for proportions of adverse events. The percentage of pain‐free patients at two hours was the primary efficacy outcome measure. We used adverse events to evaluate safety and tolerability. Secondary outcome measures included headache relief, use of rescue medication, headache recurrence, presence of nausea, and presence of vomiting. We assessed the evidence using GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) and created 'Summary of findings' tables.

Main results

We identified a total of 27 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of migraine symptom‐relieving medications, in which 9158 children and adolescents were enrolled and 7630 (range of mean age between 8.2 and 14.7 years) received medication. Twenty‐four studies focused on drugs in the triptan class, including almotriptan, eletriptan, naratriptan, rizatriptan, sumatriptan, sumatriptan + naproxen sodium, and zolmitriptan. Other medications studied included paracetamol (acetaminophen), ibuprofen, and dihydroergotamine (DHE). More than half of the studies evaluated sumatriptan. All but one study reported adverse event data. Most studies presented a low or unclear risk of bias, and the overall quality of evidence, according to GRADE criteria, was low to moderate, downgraded mostly due to imprecision and inconsistency. Ibuprofen was more effective than placebo for producing pain freedom at two hours in two small studies that included 162 children (RR 1.87, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.15 to 3.04) with low quality evidence (due to imprecision). Paracetamol was not superior to placebo in one small study of 80 children. Triptans as a class of medication were superior to placebo in producing pain freedom in 3 studies involving 273 children (RR 1.67, 95% CI 1.06 to 2.62, NNTB 13) (moderate quality evidence) and 21 studies involving 7026 adolescents (RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.47, NNTB 6) (moderate quality evidence). There was no significant difference in the effect sizes between studies involving children versus adolescents. Triptans were associated with an increased risk of minor (non‐serious) adverse events in adolescents (RD 0.13, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.18, NNTH 8), but studies did not report any serious adverse events. The risk of minor adverse events was not significant in children (RD 0.06, 95% CI − 0.04 to 0.17, NNTH 17). Sumatriptan plus naproxen sodium was superior to placebo in one study involving 490 adolescents (RR 3.25, 95% CI 1.78 to 5.94, NNTB 6) (moderate quality evidence). Oral dihydroergotamine was not superior to placebo in one small study involving 13 children.

Authors' conclusions

Low quality evidence from two small trials shows that ibuprofen appears to improve pain freedom for the acute treatment of children with migraine. We have only limited information on adverse events associated with ibuprofen in the trials included in this review. Triptans as a class are also effective at providing pain freedom in children and adolescents but are associated with higher rates of minor adverse events. Sumatriptan plus naproxen sodium is also effective in treating adolescents with migraine.

Plain language summary

Drugs for the acute treatment of migraine in children and adolescents

Background and review question

Migraine is a painful and debilitating disorder that is common in children (under 12 years of age) and adolescents (12 to 17 years of age). Common symptoms reported during a migraine attack are headache, nausea, vomiting, and sensitivity to light and sound. Many treatments for migraine are available, of which the most common are paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen), ibuprofen and other anti‐inflammatories, and triptans. Not all triptan medications are approved for use in children or adolescents, and approvals vary from country to country.

Study characteristics

In our review, we looked at 27 randomized controlled trials of drugs compared to placebo to find out which treatments were effective at providing pain freedom two hours after treatment. We also wanted to know what side effects might be caused by the treatments. A total of 7630 children received medication in the studies. The evidence is current to February 2016. Each study had between 13 and 888 participants. Their average age was 12.9 years and ranged from 8.2 to 14.7 years. Nineteen of the studies were funded by the drug manufacturer.

Key results

Ibuprofen appears to be effective in treating children with migraine, but the evidence is limited to only two small trials. Ibuprofen is readily available and inexpensive, making it an excellent first choice for migraine treatment. Paracetamol was not shown to be effective in providing pain freedom in children, but we only found one small study. Triptans are a type of medication designed specifically to treat migraine and are often effective at providing greater pain freedom in children and adolescents. The triptans examined in children included rizatriptan and sumatriptan, while almotriptan, eletriptan, naratriptan, rizatriptan, sumatriptan, and zolmitriptan were examined in adolescents. The combination of sumatriptan plus naproxen sodium is also effective at treating adolescents with migraine. Overall, there is a risk that the triptan medications may cause minor unwanted side effects like taste disturbance, nasal symptoms, dizziness, fatigue, low energy, nausea, or vomiting. The studies did not report any serious side effects.

Quality of the evidence

The overall quality of the evidence provided by the review was moderate for the triptans, but low for paracetamol and ibuprofen, as we only identified a few studies. More studies need to look at the effects of each of the migraine treatments in children and adolescents separately.

Summary of findings

Background

Migraine is a common and disabling disease, affecting 3% to 10% of children and adolescents (Stovner 2007). Children as young as two years of age may be affected, and most adults with migraine have their first headache in early childhood or adolescence (Bille 1997). Quality‐of‐life studies indicate that migraine has a significant negative impact on a child (Powers 2003; Powers 2004). Indeed, migraines can be a tremendous source of anxiety for children, adolescents, and their parents, disrupting both school obligations and parental work responsibilities. These concerns may be amplified when there is uncertainty on the physician's part as to the best treatment.

The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition, beta version (ICHD‐3 beta), provides the most accepted and current definition of migraine. The presence of headache, often associated with nausea, vomiting, or both is common to adults, adolescents, and children with migraine. However, the criteria acknowledge that children and adolescents' migraines may be shorter but will last at least two hours, and the pain may be bilateral over the frontotemporal head regions or non‐pulsatile. Adolescents, like adults, will usually begin to report unilateral pulsatile pain. The presence of photophobia and phonophobia may need to be inferred from behaviour such as a preference for a quiet and dimly lit room during a migraine attack.

Treatments for migraine include symptom‐relieving and preventive strategies. Preventive medications are used to reduce the frequency and severity of migraine attacks. Symptom‐relieving therapies commonly aim to eliminate head pain and reduce the symptoms associated with migraine, including nausea, phonophobia, and photophobia. Oral analgesics such as paracetamol and ibuprofen are the mainstay of acute therapy for migraine in children and adolescents (Hämäläinen 2002). However, other agents such as ergot derivatives (e.g. dihydroergotamine) and the serotonin 1b/1d receptor agonists (triptans) have demonstrated efficacy in adults. Many of these medications have now been studied in children and adolescents, and some are approved for use in the pediatric age group. A practice parameter on this topic has been published by the American Academy of Neurology Quality Standards Subcommittee and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society (Lewis 2004). This systematic review will summarize and update the evidence base and provide a meta‐analysis of the data.

Objectives

To assess the effects of pharmacological interventions by any route of administration versus placebo for migraine in children and adolescents 17 years of age or less. For the purposes of this review, children were defined as under 12 years of age and adolescents 12 to 17 years of age.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all prospective, placebo‐controlled trials of pharmacological interventions for symptomatic or acute treatment of migraine in children and adolescents in the outpatient setting if allocation to treatment groups was randomized (see Differences between protocol and review). We included studies regardless of design (i.e. parallel‐group or cross‐over), publication status, or language of publication. We included cross‐over studies, as migraine is an episodic disorder, and we did not expect any carry‐over or period effects (see Differences between protocol and review). We excluded non‐placebo‐controlled studies, concurrent cohort comparisons and other quasi‐ or non‐experimental designs.

Types of participants

We included studies involving pediatric participants 17 years of age or less with a diagnosis of migraine with or without aura. For the purposes of the review, we defined children as under 12 years of age and adolescents as 12 to 17 years of age (see Differences between protocol and review). We recorded inclusion age criteria, including median and mean age of subjects. We excluded studies involving both pediatric and adult patients unless they reported results separately for the pediatric patients. We analyzed separately the data from studies that included both children and adolescents when possible. If studies did not report the data separately, we used the mean age as a surrogate. If the mean age in the study was less than 12 years, we considered the study population to be of predominantly childhood age. If the mean age was greater than or equal to 12 years, we considered the study population to be of predominantly adolescent age.

Migraine is defined by clinical symptoms and signs in the 3rd edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders, beta version (ICHD‐3 beta). ICHD‐3 beta includes revised comments for the diagnosis of migraine in children and adolescents, including shorter duration of headache (2 to 72 hours), bilateral frontotemporal location, and the presence of photophobia and phonophobia as inferred from behaviour. There have been two other versions of the International Classification of Headache Disorder and a proposed revision of the 1988 criteria in the context of children or adolescents (IHS 1988; ICHD‐2; Winner 1995). We included a study in this review if investigators used any version of the International Headache Society classification systems above or the proposed revision for pediatrics for the diagnosis of migraine with or without aura.

Types of interventions

We included studies allocating participants to receive a pharmacological intervention by any route of administration for symptomatic acute treatment of a migraine attack. Acceptable comparator groups included placebo or other active drug treatments. We identified the use of preventive medication and examined this in subgroup analysis, but discontinuation was not required for inclusion.

Types of outcome measures

We chose outcomes to assess both efficacy and safety. We selected the primary efficacy outcome based on the suggested guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine (Tfelt‐Hansen 2012). The primary outcome for safety was based on the report of adverse events. All outcome measures were reported for the treatment of a single attack (see Differences between protocol and review).

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome measure for efficacy was the percentage of pain‐free participants at two hours; we defined pain freedom as the absence of pain at two hours before the use of additional or rescue medication (see Differences between protocol and review). Headache relief is a frequently used primary outcome measure that is variably defined based on the scale used to assess pain. For example, if using the four level scale of none, mild, moderate, or severe pain, investigators or physicians may define headache relief as a decrease in pain from moderate or severe to mild or none. Some in the migraine research community have challenged the use of headache relief as a primary outcome measure; for example, migraine sufferers generally do not consider headache relief a success and expect pain freedom from an intervention (Davies 2000; Lipton 2002). Given these considerations, we classified headache relief as a secondary outcome measure (see Differences between protocol and review).

We used the percentage of participants with any adverse event(s) as the primary safety outcome measure, and this was required for inclusion in the analysis (see Differences between protocol and review). We defined adverse events as any unwanted effect that occurred during treatment. We also documented the proportion of participants reporting any serious adverse events when possible. Serious adverse events included death, any life‐threatening condition, hospitalization, disability or permanent damage, required intervention to prevent permanent damage, or any other important medical event that could jeopardize the participant or require medical or surgical intervention.

Some aspects of the original protocol were not necessary to implement given the way studies reported outcome data. We document these considerations in the Differences between protocol and review section.

Secondary outcomes

We assessed the following secondary outcome measures.

Headache relief (headache response): the percentage of participants with headache relief at two hours is typically defined as a decrease in headache intensity from severe or moderate to mild or none at two hours prior to the use of rescue medication. When studies used alternate definitions of pain intensity (e.g. numerical scale), they needed to describe a level of relief that would be meaningful to a participant and to reflect a decrease in headache intensity similar to that assumed in the above definition.

Rescue medication: the percentage of participants taking rescue medication at two hours or earlier to a maximum of six hours after the test drug. The definition of rescue medication was variable and often included any use of medication to treat the recurrence of headache within a specified timeframe (i.e. usually 24 hours). For the purposes of the review, rescue medication was defined as the use of any medication between 2 and 24 hours.

Headache recurrence: the percentage of participants who were initially pain‐free or achieved the study primary outcome of headache relief within 2 hours without the use of rescue medication but who experienced recurrence of any headache from 2 to 48 hours.

Presence of nausea: percentage of participants with nausea at two hours after taking the test drug.

Presence of vomiting: percentage of participants with vomiting within two hours of taking the test drug.

We did not include participant preference, presence of photophobia, or presence of phonophobia in the analysis as originally planned in the protocol (see Differences between protocol and review).

Search methods for identification of studies

We conducted a search of electronic databases in collaboration with a research librarian using search strategies to identify the highest level of evidence for the topic. In addition, we manually searched other sources listed below.

Electronic searches

We systematically searched the following databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (1991 to 2013, Issue 3).

OvidSP MEDLINE (1946 to February 2016).

Ovid MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations (2012 to February 2016).

EMBASE (1980 to February 2016).

Database of Abstracts and Reviews of Effects (1991 to April 2013).

International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (1970 to April 2013).

PsycINFO (1806 to April 2013).

EBSCOhost CINAHL (Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health) (1937 to April 2013).

The search strategies used a combination of text words and medical subject headings (MeSH), adapted for each database searched: concepts included migraine, headache, cephalgia or cephalalgia, drug therapy, drug treatment, antimigraine therapy, antimigraine treatment, and treatment outcome, combined with drugs and acute treatments known to be used for migraine in children and adolescents. These terms were combined with a pediatric filter designed by the librarian (Lisa Tjosvold) of the Cochrane Child Health Field.

Complete search strategies are given in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We conducted a gray literature search including reviewing the reference lists of included studies and handsearching meeting abstracts from the American Headache Society and International Headache Society Scientific meetings. The review authors attempted to contact primary authors, experts in the area, and drug manufacturers (GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Ortho‐McNeil, Merck, and Pfizer) for information on recent, ongoing, or unpublished trials. We searched ClinicalTrials.gov for new or ongoing studies and used Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled-trials.com) to search across multiple trial registries. GlaxoSmithKline (www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com) and AstraZeneca (www.astrazenecaclinicaltrials.com) have clinical trial registries and report on both published and unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We identified potentially relevant articles by reviewing the titles and abstracts from the original search. We considered studies with insufficient information in the title or abstract as potentially relevant articles for further assessment. We then reviewed the full text of potentially relevant studies for inclusion or exclusion. Two reviewers independently carried out both steps. A third, independent reviewer resolved any disagreements that arose between them.

Data extraction and management

One reviewer used a standardized data abstraction form to extract data, which a second reviewer then checked for accuracy and completeness. We recorded extracted data in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014). A third, independent reviewer resolved discrepancies.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two reviewers assessed risk of bias using the 'Risk of bias' table for each study. Reviewers assessed five domains before making a judgement: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreements by discussion. We did not use the Jadad scale as planned in the protocol, as per current recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration (Differences between protocol and review).

Assessment of quality of evidence in included studies

We assessed the overall quality of the evidence for each outcome using the GRADE system and included our assessment in the 'Summary of findings' tables in order to present the main findings of the review in a transparent and simple tabular format (GRADEPro 2015). In particular, we included key information concerning the quality of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on the main outcomes.

The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning a level of evidence.

High: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low: any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

We decreased the grade if we found:

serious (− 1) or very serious (− 2) limitations to study quality;

important inconsistency(s) (− 1);

some (− 1) or major (− 2) uncertainty about directness;

imprecise or sparse data (− 1);

high probability of reporting bias (− 1).

'Summary of findings' table

We decided post hoc to include four 'Summary of findings' tables to present the main findings in a transparent and simple tabular format. In particular, we included key information concerning the quality of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on the outcomes pain freedom at 2 hours and adverse events, for the four main comparisons.

Measures of treatment effect

We reported the risk ratio (RR) for all primary and secondary efficacy outcome measures with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) as well as the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB). We reported the risk difference (RD) with 95% CIs for the adverse events as the primary measure of harm as well as the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH).

Unit of analysis issues

We included cross‐over trials with binary outcomes in the analysis (Curtin 2002). None of the cross‐over trials reported any significant carry‐over or period effects, and none would be expected based on the acute episodic nature of migraine.

Dealing with missing data

We only analyzed the available data for all outcomes. We assessed the possibility of missing studies as described below (see Assessment of reporting biases). We considered variability in the reporting of outcomes to be random.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. We interpreted the I2 statistic as suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting biases qualitatively by visually examining the funnel plot and quantitatively using a modified version of Egger's test (Egger 1997; Harbord 2006), as implemented in the metabias module for Stata statistical software package on the triptan versus placebo studies in adolescents using the pain‐free outcome (Stata 14).

Data synthesis

We pooled studies using a Mantel‐Haenszel, random‐effects model. We pooled dichotomous outcomes, and calculated RRs with 95% CIs. We calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) for RRs of the primary outcome that were statistically significant. For adverse events, we combined data combined using RDs with 95% CIs. We calculated the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) for RDs of adverse events that were statistically significant. We included studies with small sample sizes and imprecise effect estimates, but we graded them lower for quality and weighted them accordingly in the meta‐analyses.

We combined trials of cross‐over design with parallel group trials in the meta‐analysis. We included outcome measures from each intervention period in the analysis as if the trial were a parallel group trial. We also included three‐way cross‐over studies with two intervention periods and one placebo period as if they were a parallel group trial, but we divided the placebo period in two to avoid double counting the placebo interventions. Paired analysis was not possible for any of the included studies (see Differences between protocol and review). This method of including cross‐over studies will tend to produce wider confidence intervals and is considered a more conservative assessment of treatment effect given that these studies will receive a lower weight in the meta‐analyses. We included study design in the sensitivity analysis to assess the influence of cross‐over design on our final conclusions.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We used the I2 statistic to determine the presence of heterogeneity and test for subgroup differences as implemented in RevMan, used to prepare this review (Higgins 2002; RevMan 2014). We performed all subgroup analyses for the pain‐free outcome measure using the placebo‐controlled studies of triptan medications versus placebo in adolescents (except for the age‐based subgroup analysis).

Post hoc subgroup analyses included the following.

Intranasal route.

Preventive medication permitted during the study.

Sensitivity analysis

We examined potential sources of heterogeneity using the following a priori sensitivity analyses (see Differences between protocol and review).

Allocation concealment (low, unclear, or high risk of bias).

Cross‐over versus parallel‐group study design.

Source of funding (pharmaceutical, non‐pharmaceutical, or unclear).

Reported in a peer‐reviewed indexed journal.

Small sample size ≤ 50.

We performed all sensitivity analyses for the pain‐free primary outcome using the studies of triptan medications versus placebo in adolescents.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

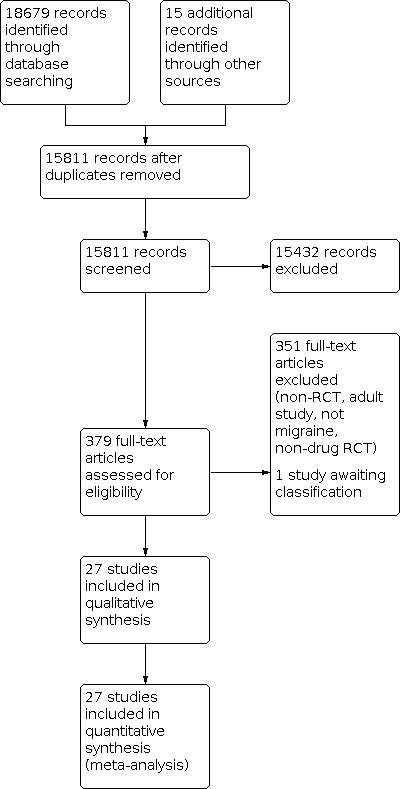

The literature search and review of the gray literature yielded 15,811 unique citations, 379 of which we assessed as full‐text articles for eligibility. Some of our data requests to manufacturers were met with referrals to trial registry websites or data were not made available. A total of 27 randomized placebo‐controlled trials of acute drug therapy for migraine met our inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The mean age of inclusion was 12.9 years with a range of means between 8.2 and 14.7 years. The minimum age of inclusion was 4 years in one study (Hämäläinen 1997a), and the maximum age for inclusion was 18 years in two studies (Evers 2006; Hämäläinen 1997b). Three studies included only children under 12 (Hämäläinen 2002; Lewis 2002; Ueberall 1999), and one study reported data for children and adolescents separately (Ho 2012). Six studies included children and adolescents, but they did not report the data separately (Ahonen 2004; Ahonen 2006; Evers 2006; Hämäläinen 1997a; Hämäläinen 1997b; Hämäläinen 1997c). Participants in two of the studies reporting children and adolescents combined had a mean age of less than 12 years and were included in the analysis as studies of predominantly children (Hämäläinen 1997a; Hämäläinen 1997c). Participants in the remaining four studies where children and adolescents were combined had a mean age of greater than 12 years, and we considered them to be studies of predominantly adolescents for the analysis. Finally, 17 studies included only adolescents over the age of 12 years (Callenbach 2007; Derosier 2012; Fujita 2014; Lewis 2007; Linder 2008; NCT01211145; Rothner 1997; Rothner 1999a; Rothner 1999b; Rothner 1999c; Rothner 2006; Visser 2004a; Winner 1997; Winner 2000; Winner 2002; Winner 2006; Winner 2007). The mean number of participants randomized was 359 with a range of 13 to 888. We summarize the characteristics of included studies in Table 5, and we summarize the individual studies in Table 6. We provide more details, including a risk of bias assessment, in Characteristics of included studies.

1. Summary of characteristics of included studies.

| Study characteristics | Criteria | N= 27a | % |

|

Study design |

Parallel | 16 | 59% |

| Cross‐over | 11 | 41% | |

|

Sponsorship |

Pharmaceutical | 19 | 70% |

| Non‐pharmaceutical | 5 | 19% | |

| Unclear | 3 | 11% | |

|

Age inclusion criteria |

Adolescents (12‐17 years) | 17 | 63% |

| Children and adolescents | 6 | 22% | |

| Children (< 12 years) | 4 | 15% | |

|

Pain scale |

4‐point scale | 21 | 78% |

| 5‐faces scale | 5 | 18% | |

| VAS | 1 | 4% | |

|

Preventive medication permitted? |

Yes | 9 | 33% |

| No | 13 | 48% | |

| Unclear | 5 | 19% | |

|

Route of delivery |

Oral | 19 | 70% |

| Intranasal | 8 | 30% | |

|

Medications |

Paracetamol | 1 | 4% |

| Ibuprofen | 3 | 7% | |

| Triptans | 24 | 85% | |

| DHE | 1 | 4% | |

|

Triptan medications |

Almotriptan | 1 | 4% |

| Eletriptan | 1 | 4% | |

| Naratriptan | 1 | 4% | |

| Rizatriptan | 4 | 17% | |

| Sumatriptan | 12 | 50% | |

| Sumatriptan + naproxen sodium | 1 | 4% | |

| Zolmitriptan | 4 | 17% |

DHE: dihydroergotamine; VAS: visual analogue scale.

aThe total number of studies listed in Medications does not add up to 27 as two studies (Hämäläinen 1997a & Evers 2006) compared multiple medications.

2. Summary table of included studies.

| Review Manager ID | Study design | Agent | Route |

Child. (< 12 yrs) |

Adolesc. (12‐17 yrs) |

Mean age | No | % Female |

| Paracetamol | ||||||||

| Hämäläinen 1997a | Cross‐over | — | PO | Yes | Yes | 10.7 | 80 | 50% |

| Ibuprofen | ||||||||

| Hämäläinen 1997a | Cross‐over | — | PO | Yes | Yes | 10.7 | 78 | 50% |

| Lewis 2002 | Parallel | — | PO | Yes | No | 9.0 | 84 | ND |

| Evers 2006 | Cross‐over | — | PO | Yes | Yes | 13.9 | 29 | 56% |

| Triptans (< 12 years) | ||||||||

| Ho 2012 | Parallel | Rizatriptan | PO | Yes | NA | ND | 200 | 44% |

| Ueberall 1999 | Cross‐over | Sumatriptan | IN | Yes | No | 8.2 | 14 | 50% |

| Hämäläinen 2002 | Cross‐over | Sumatriptan | IN | Yes | No | 9.7 | 59 | 54% |

| Triptans (12‐17 years) | ||||||||

| Linder 2008 | Parallel | Almotriptan | PO | No | Yes | 14.4 | 714 | 60% |

| Winner 2007 | Parallel | Eletriptan | PO | No | Yes | 14.0 | 274 | 57% |

| Rothner 1997 | Parallel | Naratriptan | PO | No | Yes | 14.3 | 300 | 54% |

| Ho 2012 | Parallel | Rizatriptan | PO | NA | Yes | ND | 570 | 61% |

| Visser 2004a | Parallel | Rizatriptan | PO | No | Yes | 14.2 | 476 | 55% |

| Winner 2002 | Parallel | Rizatriptan | PO | No | Yes | 14.0 | 296 | 54% |

| Ahonen 2006 | Cross‐over | Rizatriptan | PO | Yes | Yes | 12.0 | 116 | 54% |

| Callenbach 2007 | Cross‐over | Sumatriptan | IN | No | Yes | 13.6 | 46 | 78% |

| Rothner 1999b | Parallel | Sumatriptan | PO | No | Yes | 13.6 | 92 | 52% |

| Winner 2000 | Parallel | Sumatriptan | IN | No | Yes | 14.1 | 507 | 52% |

| Hämäläinen 1997b | Cross‐over | Sumatriptan | PO | Yes | Yes | 12.3 | 23 | 52% |

| Rothner 1999c | Parallel | Sumatriptan | PO | No | Yes | 13.5 | 102 | 42% |

| Fujita 2014 | Parallel | Sumatriptan | PO | Yes | Yes | 14.1 | 144 | 58% |

| Winner 1997 | Cross‐over | Sumatriptan | PO | No | Yes | 13.9 | 298 | 58% |

| Winner 2006 | Parallel | Sumatriptan | IN | No | Yes | 14.3 | 731 | 55% |

| Ahonen 2004 | Cross‐over | Sumatriptan | IN | Yes | Yes | 12.4 | 94 | 46% |

| Rothner 1999a | Parallel | Sumatriptan | PO | No | Yes | 14.1 | 273 | 57% |

| Derosier 2012 | Parallel | Sumatriptan and Naproxen Sodium |

PO | No | Yes | 14.7 | 490 | 59% |

| Lewis 2007 | Cross‐over | Zolmitriptan | IN | No | Yes | 14.2 | 171 | 57% |

| Evers 2006 | Cross‐over | Zolmitriptan | PO | Yes | Yes | 13.9 | 29 | 56% |

| Rothner 2006 | Parallel | Zolmitriptan | PO | No | Yes | 14.2 | 696 | 59% |

| NCT01211145 | Parallel | Zolmitriptan | IN | No | Yes | 14 | 584 | ND |

| Dihydroergotamine | ||||||||

| Hämäläinen 1997c | Cross‐over | — | PO | Yes | Yes | 10.3 | 13 | 38% |

IN: intranasal; NA: not applicable; ND: no data available; No: total number in efficacy analysis (intention‐to‐treat when available); PO: per os (by mouth).

Excluded studies

We excluded two studies, one that compared intravenous prochlorperazine versus ketorolac in children and adolescents presenting to the Emergency Department (ED) (Brousseau 2004) and one that compared intravenous metoclopramide to placebo in children and adolescents presenting to the ED (NCT00355394) from the analysis as our review is focused on outpatient acute drug therapy. All other excluded studies were either not controlled or were non‐drug clinical trials (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Awaiting classification

A single study was recently published and is awaiting classification (Winner 2015). It is a cross‐over study of sumatriptan + naproxen sodium in adolescents (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

Risk of bias in included studies

We illustrated the risk of bias in included studies in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Investigators described all studies as randomized (low risk of selection bias (random sequence generation)), but the method of randomization was unclear in 19 studies (unclear risk of bias). Authors frequently employed generic descriptions of sequence generation such as 'randomized 1:1' or 'block randomization to two age groups'. Eight studies adequately reported allocation concealment, and we judged them to be at low risk of selection bias (allocation concealment). We judged the remaining 19 studies to be at unclear risk of bias for this domain.

Blinding

Generally, authors described all studies as double‐blind, but 17 studies did not report their methods for blinding clearly (unclear risk of bias). All studies were either an oral or intranasal medication compared with placebo. Studies seldom described efforts to match for taste, color, smell, etc. We considered 10 studies to be at low risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

We considered incomplete reporting of outcome data to confer a high risk of bias in Winner 2002 and an unclear risk in Hämäläinen 1997c. We considered the remaining 25 studies to be at low risk.

Selective reporting

Six studies were reported only in the sponsors' clinical trial report registry and published only in abstract form (Hämäläinen 2002; Rothner 1997; Rothner 1999a; Rothner 1999b; Rothner 1999c; Winner 1997), while one study was reported only in the sponsor's clinical trial report registry (NCT01211145). All included studies reported the pain‐free primary efficacy outcome. The reports available through the sponsors' clinical trial registries were comprehensive in reporting all planned outcome measures and greatly enhanced the reported data that was published in abstract form. Also, there were no discrepancies between published abstracts and the reports released through the sponsor's clinical trial registry. Derosier 2012 was the only study that did not report the headache relief secondary outcome, and Lewis 2002 did not report adverse event data; we judged these two studies to be at unclear risk of bias for this domain. We judged the remaining 25 studies to be at low risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

We assessed publication bias based on the pain‐free outcome for all triptans versus placebo in adolescents. On visual inspection, the funnel plot showed some asymmetry (Figure 4), suggesting the possibility of publication or other sources of bias and small‐study effects. We used Egger's test to explore small‐study effects, which were not significant (P = 0.139). The inclusion of published and unpublished data from the clinical trial registries would suggest a reduced risk of publication bias, as many of these studies were negative.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 7 Triptans vs placebo in Adolescents, outcome: 7.1 Pain‐free.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Summary of findings 1. Should ibuprofen be used to treat children with migraine?

| Ibuprofen compared with placebo in children with migraine | |||||

| Patient or population: acute treatment of migraine in children Setting: ambulatory Intervention: ibuprofen Comparison: placebo | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effectsa (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Response with placebo | Response with Ibuprofen | ||||

| Pain freedom at 2 h | Study population | RR 1.87 (1.15 to 3.04) | 125 (2 RCTs) | ⨁⨁◯◯b,c Low | |

| 267 per 1000 | 499 per 1000 (307 to 811) | ||||

| Adverse events | 100 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (− 13 to 13) |

RD 0.00 (− 0.13 to 0.13) |

80 (1 RCT) |

|

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence

High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; RD: risk difference | |||||

aThe response in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). bIn the two studies, there were no serious risks of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, or publication bias. We downgraded quality of evidence by two levels due to very serious imprecision (small sample size, few events, and wide confidence interval).

cHigh (⨁⨁⨁⨁) = further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect; Moderate (⨁⨁⨁◯) = further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate; Low (⨁⨁◯◯) = further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate; Very Low (⨁◯◯◯) = any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

Summary of findings 2. Should triptans be used to treat children with migraine?

| Triptans compared with placebo in children with migraine | ||||||

| Patient or population: acute treatment of migraine in children Setting: ambulatory Intervention: triptans Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effectsa (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Response with placebo | Response with triptans | |||||

| Pain freedom at 2 h | Study population | RR 1.67 (1.06 to 2.62) | 345 (3 RCTs) | ⨁⨁⨁◯b,c MODERATE | Includes rizatriptan oral (1 study) and sumatriptan by nasal spray (2 studies) | |

| 276 per 1000 | 461 per 1000 (292 to 723) | |||||

| Adverse events | 176 per 1000 | 11 per 1000 (− 7 to 30) |

RD 0.06 (− 0.04 to 0.17) |

420 (3 RCTs) |

||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence

High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; RD: risk difference. | ||||||

aThe response in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed response in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). bIn the three studies, there were no serious risks of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, or publication bias detected. Quality of evidence was downgraded by one level due to serious imprecision (small sample size, few events, and wide confidence interval).

cHigh (⨁⨁⨁⨁) = further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect; Moderate (⨁⨁⨁◯) = further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate; Low (⨁⨁◯◯) = further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate; Very Low (⨁◯◯◯) = any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

Summary of findings 3. Should triptans be used to treat adolescents with migraine?

| Triptans compared with placebo in adolescents with migraine | ||||||

| Patient or population: acute treatment of migraine in adolescents Setting: ambulatory Intervention: Triptans Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effectsa (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Response with placebo | Response with Triptans | |||||

| Pain freedom at 2 h | Study population | RR 1.32 (1.19 to 1.47) | 6761 (21 RCTs) | ⨁⨁⨁◯b,c MODERATE | Includes almotriptan (1 study), eletriptan (1 study), naratriptan (1 study), rizatriptan (4 studies), sumatriptan (10 studies), and zolmitriptan (4 studies) | |

| 230 per 1000 | 303 per 1000 (273 to 338) | |||||

| Adverse events | 184 per 1000 | 24 per 1000 (15 to 33) |

RD 0.13 (0.08 to 0.18) |

7876 (21 RCTs) |

||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence

High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; RD: risk difference. | ||||||

aThe response in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed response in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). bSerious inconsistency was observed in the effect estimates. All of the triptans with only 1 study were not statistically superior to placebo (i.e. almotriptan, eletriptan, naratriptan) in producing pain freedom while the three triptans with 2 or more studies (i.e. rizatriptan, sumatriptan, and zolmitriptan) were statistically significant with a higher magnitude of effect. In the subgroup analysis of the individual triptan groups through, the subgroup differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.45).

cHigh (⨁⨁⨁⨁) = further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect; Moderate (⨁⨁⨁◯) = further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate; Low (⨁⨁◯◯) = further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate; Very Low (⨁◯◯◯) = any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

Summary of findings 4. Should sumatriptan plus naproxen sodium be used to treat adolescents with migraine?

| Sumatriptan + naproxen sodium compared with placebo in adolescents with migraine | ||||||

| Patient or population: acute treatment of migraine in adolescents Setting: ambulatory Intervention: sumatriptan + naproxen sodium Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effectsa (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Response with placebo | Response with Sumatriptan + naproxen sodium | |||||

| Pain freedom at 2 h | Study population | RR 2.66 (1.57 to 4.51) | 485 (1 RCT) | ⨁⨁⨁◯b,c MODERATE | Doses including sumatriptan + naproxen 10 mg + 60 mg, 30 mg + 180 mg, and 85 mg + 500 mg were all well tolerated and demonstrated similar efficacy | |

| 99 per 1000 | 262 per 1000 (163 to 394) | |||||

| Adverse events | 83 per 1000 | 2 per 1000 (− 2 to 7) |

RD 0.03 (− 0.02 to 0.09) |

490 (1 RCT) |

||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence

High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; RD: risk difference. | ||||||

aThe response in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed response in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). bThe confidence interval of the effect size is wide. The true effect may be substantially different than the estimated effect in producing pain freedom.

cHigh (⨁⨁⨁⨁) = further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect; Moderate (⨁⨁⨁◯) = further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate; Low (⨁⨁◯◯) = further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate; Very Low (⨁◯◯◯) = any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

We describe the measures of effect for each of the interventions below. In addition, we present 'Summary of findings' tables for all comparisons for which there was more than one study.

Paracetamol versus placebo in children

In the one three‐way cross‐over study that evaluated paracetamol (Hämäläinen 1997a), the participant age ranged from 4 to 15.8 years (N = 88), but investigators did not report results for children and adolescents separately. However, the mean age of inclusion was 10.7 years, so we deemed the study to be predominantly in children. Paracetamol was not superior to placebo for the pain‐free outcome ( RR 1.40, 95% CI 0.75 to 2.58). There was no statistically significant difference in headache relief (defined as a reduction in pain by two grades on a five point scale), rescue medication, headache recurrence, or adverse events. The study did not report the presence of nausea or vomiting.

Ibuprofen versus placebo in children

Ibuprofen was superior to placebo in the pooled analysis of two studies (Figure 5) ‐ Hämäläinen 1997a was a three‐way cross‐over study with paracetamol, with a mean participant age of 10.7 years (N = 88), and Lewis 2002 was a parallel group study that included only 6 to 12 year‐olds with a mean age of 9 years (N = 84). For the pain‐free primary outcome, the RR was 1.87 (95% CI 1.15 to 3.04; Analysis 1.1) with a NNTB of 4. Ibuprofen was also superior to placebo for headache relief (Analysis 1.3) but not for rescue medication (Analysis 1.4) or headache recurrence (Analysis 1.5). There was no difference in the proportion of adverse events between groups (Analysis 1.2). Lewis 2002 did not report adverse events, and Hämäläinen 1997a did not report on the presence of nausea and vomiting.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Ibuprofen vs placebo in Children, outcome: 2.1 Pain‐free.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Ibuprofen vs placebo in children, Outcome 1: Pain‐free

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Ibuprofen vs placebo in children, Outcome 3: Headache relief

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Ibuprofen vs placebo in children, Outcome 4: Rescue medication

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Ibuprofen vs placebo in children, Outcome 5: Headache recurrence

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Ibuprofen vs placebo in children, Outcome 2: Adverse events (any)

The quality of evidence for the pain‐free outcome was low, downgraded by two levels due to very serious imprecision (Table 1).

Ibuprofen versus placebo in adolescents

One small three‐way cross‐over study examined ibuprofen, zolmitriptan, and placebo (Evers 2006). While it included both children and adolescents, the mean participant age was 13.9 years (N = 29), so we considered the study to be predominantly in adolescents. Headache relief at two hours was the primary outcome measure reported, but investigators also reported pain freedom at two hours. The pain‐free outcome was not statistically significant (RR 7.00, 95% CI 0.99 to 49.69), but ibuprofen was statistically superior to placebo for headache relief (RR 2.50, 95% CI 1.02 to 6.10). There were no significant differences in other secondary outcome measures, including use of rescue medication, headache recurrence, presence of nausea, or presence of vomiting. There was no significant difference in adverse events observed.

Triptans versus placebo in children

Three studies examined two triptan medications in children under 12 years of age: rizatriptan (Ho 2012, N = 200) and sumatriptan (Hämäläinen 2002, N = 59; Ueberall 1999, N = 14). Triptans as a class of medication were superior to placebo in children for the primary outcome measure of pain freedom (RR 1.67, 95% CI 1.06 to 2.62; Analysis 2.1) with a NNTB of 13. There were no statistically significant differences in the effect size between rizatriptan and sumatriptan subgroups. Overall, we did not observe any statistically significant difference in the secondary outcomes of headache relief (Analysis 2.3), rescue medication (Analysis 2.4), headache recurrence (Analysis 2.5), presence of nausea (Analysis 2.6), or presence of vomiting (Analysis 2.7). There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of adverse events observed in the triptan versus placebo groups (Analysis 2.2).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Triptans vs placebo in children, Outcome 1: Pain‐free

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Triptans vs placebo in children, Outcome 3: Headache relief

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Triptans vs placebo in children, Outcome 4: Rescue medication

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Triptans vs placebo in children, Outcome 5: Headache recurrence

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Triptans vs placebo in children, Outcome 6: Presence of nausea

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Triptans vs placebo in children, Outcome 7: Presence of vomiting

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Triptans vs placebo in children, Outcome 2: Adverse events (any)

The quality of evidence for the pain‐free outcome was moderate, downgraded by one level due to serious imprecision (Table 2).

Triptans versus placebo in adolescents

Triptans as a class of medications were superior to placebo in adolescents for the acute treatment of migraine (Figure 6). Overall the pain‐free RR was 1.32 (95% CI 1.19 to 1.47; Analysis 3.1) with a NNTB of 6 and low (I2 = 26%), non‐significant heterogeneity (P = 0.13) between studies. Triptans for which there were two or more studies were statistically superior to placebo as a subgroup (Figure 6), but subgroup differences in effect size were not statistically significant. The individual triptans included were almotriptan (Linder 2008, N = 714), eletriptan (Winner 2007, N = 274), naratriptan (Rothner 1997, N = 300), rizatriptan (Ahonen 2006, N = 96; Winner 2002, N = 296; Ho 2012, N = 570; Visser 2004a, N = 476), sumatriptan (Ahonen 2004, N = 83; Callenbach 2007, N = 46; Fujita 2014, N = 144; Hämäläinen 1997b, N = 23; Rothner 1999a, N = 273; Rothner 1999b, N = 92; Rothner 1999c, N = 102; Winner 1997, N = 298; Winner 2000, N = 507; Winner 2006, N = 731), and zolmitriptan (Evers 2006, N = 29; Lewis 2007, N = 171; NCT01211145, N = 584; Rothner 2006, N = 696). There was, however, an increased risk of minor (non‐serious) adverse events in the triptan group when compared with placebo, with an RD of 0.13 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.18; Analysis 3.2) and NNTH of 8. The secondary efficacy outcomes that favoured triptans were headache relief (RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.24; Analysis 3.3), a reduction in the use of rescue medication (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.87; Analysis 3.4), and reduced risk of headache recurrence (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.93; Analysis 3.5). There were no statistically significant differences in the presence of nausea (Analysis 3.6) or vomiting (Analysis 3.7).

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 7 Triptans vs placebo in Adolescents, outcome: 7.1 Pain‐free.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Triptans vs placebo in adolescents, Outcome 1: Pain‐free

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Triptans vs placebo in adolescents, Outcome 2: Adverse events (any)

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Triptans vs placebo in adolescents, Outcome 3: Headache relief

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Triptans vs placebo in adolescents, Outcome 4: Rescue medication

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Triptans vs placebo in adolescents, Outcome 5: Headache recurrence

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Triptans vs placebo in adolescents, Outcome 6: Presence of nausea

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Triptans vs placebo in adolescents, Outcome 7: Presence of vomiting

The quality of evidence for the pain‐free outcome was moderate, downgraded by one level due to serious inconsistency (Table 3).

Sumatriptan plus naproxen sodium versus placebo in adolescents

We included one study of sumatriptan plus naproxen sodium versus placebo. The study included adolescents with a mean age of 14.7 years and randomized a total of 683 participants. The doses of sumatriptan + naproxen sodium, respectively, were 10 mg + 60 mg (N = 96), 30 mg + 180 mg (N = 97), and 85 mg + 500 mg (N = 152). The primary outcome reported was pain freedom at two hours, with data adjusted for age and baseline severity. The adjusted pain‐free rates at two hours were higher with sumatriptan + naproxen sodium 10 mg + 60 mg (29%; adjusted P = 0.003), 30 mg + 180 mg (27%; adjusted P = 0.003), and 85 mg + 500 mg (24%; adjusted P = 0.003) versus placebo (10%). Post hoc analyses showed no differences among the 3 doses or an age‐by‐treatment interaction. Calculating the RR for pain relief at 2 hours, sumatriptan + naproxen sodium was superior to placebo with an RR of 3.25 (95% CI 1.78 to 5.94) and NNTB of 6. The use of rescue medication was also significantly reduced with the combination medication when compared with placebo (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.64), but investigators did not report headache relief. There was no statistically significant increase in adverse events and no difference in the presence of nausea. Headache recurrence and presence of vomiting were also not reported.

The quality of evidence for the pain‐free outcome was moderate, downgraded by one level due to the width of the confidence interval of the effect size (Table 4).

Dihydroergotamine (DHE) versus placebo in children

One small cross‐over study of dihydroergotamine versus placebo included children and adolescents aged 5 to 15 years (Hämäläinen 1997c, N = 13). With a mean participant age of 10.3 years, we considered the study to be predominantly in children. DHE demonstrated no significant difference in the pain‐free outcome or any of the secondary outcomes, including headache relief or the use of rescue medications. There was no statistically significant increase in the proportion of adverse events between DHE and placebo. Authors did not report headache recurrence, presence of nausea, or the presence of vomiting.

Subgroup analysis for other sources of heterogeneity

We assessed potentially important sources of clinical heterogeneity using the pain‐free outcome of triptan studies in adolescents. Tests for subgroup differences showed that effect size estimates for intranasal studies of sumatriptan and zolmitriptan were significantly higher than oral triptan studies of almotriptan, eletriptan, naratriptan, rizatriptan, sumatriptan, and zolmitriptan (P = 0.02, I2 = 81.5%, Analysis 4.1). We observed a statistically significant difference in the comparison of oral versus intranasal zolmitriptan studies, where intranasal delivery was associated with a significantly higher effect size for the pain‐free outcome (P = 0.04)=, I2 = 77.1%; Analysis 4.3). However, the difference was not statistically significant when comparing oral versus intranasal sumatriptan studies (Analysis 4.2). The permitted concomitant use of migraine preventive medications in the triptan trials among adolescents was not associated with any significant difference in the effect size (Analysis 4.4). We did not observe any statistically significant differences in the overall effect size estimates between the triptan versus placebo studies that included only children, those where children and adolescents were mixed and not reported separately, and those studies that examined adolescents exclusively (P = 0.42, I2 = 0%; Analysis 5.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Triptans vs placebo in adolescents, subgroup analysis, Outcome 1: Pain‐free by route (oral or intranasal)

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Triptans vs placebo in adolescents, subgroup analysis, Outcome 3: Zolmitriptan vs placebo by route (oral or intranasal)

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Triptans vs placebo in adolescents, subgroup analysis, Outcome 2: Sumatriptan vs placebo by route (oral or intranasal)

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Triptans vs placebo in adolescents, subgroup analysis, Outcome 4: Pain‐free by preventive medication

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Triptans vs placebo by age, subgroup analysis, Outcome 1: Age group

Sensitivity analysis of other study characteristics

The overall heterogeneity was low for the triptan versus placebo studies in adolescents for the pain‐free outcome (Tau2 = 0.01; Chi2 = 27.15, degrees of freedom (df) = 20 (P = 0.13); I2 = 26%). We performed a sensitivity analysis to explore the effects of sponsorship; risk of bias in allocation concealment; study design (cross‐over versus parallel group); type of study report (journal article versus clinical trial registry and abstract); and small sample size (< 50). The cross‐over study design was associated with significantly higher effect size estimates for the pain‐free outcome (P = 0.004, I2 = 88.2%; Analysis 6.1). The effect estimate for the triptan versus placebo studies in adolescents was similar in direction, magnitude, and significance (i.e. RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.39) when we removed studies of cross‐over design. Similarly studies with a sample size of less than 50 had a significantly higher estimates of treatment effect (P = 0.03, I2 = 79.4%; Analysis 6.5). The overall effect estimate without studies having small sample sizes was similar to the reported effect estimate (RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.46). There were no significant subgroup difference for allocation concealment (Analysis 6.2), source of funding (Analysis 6.3), or type of study report (Analysis 6.4).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Triptans vs placebo in adolescents, sensitivity analysis, Outcome 1: Study design

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Triptans vs placebo in adolescents, sensitivity analysis, Outcome 5: Sample size

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Triptans vs placebo in adolescents, sensitivity analysis, Outcome 2: Allocation concealment

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Triptans vs placebo in adolescents, sensitivity analysis, Outcome 3: Source of funding

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Triptans vs placebo in adolescents, sensitivity analysis, Outcome 4: Reported in a journal

Discussion

Summary of main results

In total, we identified 27 moderate quality studies for inclusion. Most were at a low or unclear risk of bias and of varying size (a range of 13 to 888 participants in total). The mean age of inclusion was 12.9 years with a range of means between 8.2 and 14.7 years.

Paracetamol

There is insufficient evidence in favor of paracetamol for the acute treatment of migraine in children or adolescents. We only identified one small cross‐over study, predominantly in children, where oral paracetamol was not superior to placebo or ibuprofen.

Ibuprofen

Ibuprofen was more effective than placebo in producing pain freedom in two small studies involving children. In one small cross‐over study in adolescents, ibuprofen was not superior to placebo for pain freedom, but it was for headache relief (Evers 2006). While ibuprofen as a non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAID) may have some advantage in the treatment of a migraine attack, considering the presence of neurogenic inflammation (Levy 2008), it was not superior to zolmitriptan or paracetamol in two three‐way cross‐over studies (Evers 2006; Hämäläinen 1997a). Ibuprofen was not associated with an increase in adverse events overall.

Triptans

Triptans as a class of medication were more effective than placebo in producing pain freedom in 3 studies involving children and 21 studies involving adolescents. We did not observe any significant differences in the effect sizes between the subgroups of individual triptans, including almotriptan, eletriptan, naratriptan, rizatriptan, sumatriptan, or zolmitriptan. While there was some evidence to suggest that intranasal preparations of sumatriptan and zolmitriptan produce higher effect sizes than oral preparations of all the triptans listed above, the evidence was inconsistent. Evidence for the efficacy of the triptans was variable, as measured through the secondary outcomes of headache relief, use of rescue medication, headache recurrence, presence of nausea, and presence of vomiting, but in general it favored the triptans. The efficacy, however, is counterbalanced with an increased risk of minor (non‐serious) adverse events overall. However, there were no serious adverse events reported. Commonly reported adverse events included fatigue, dizziness, asthenia, dry mouth, and nausea or vomiting with oral preparations, and taste disturbance, nasal symptoms, and nausea with intranasal preparations. The combination of sumatriptan with naproxen sodium was also more effective than placebo in producing pain freedom in one adolescent study. We did not observe any significant differences in the effect sizes between studies that included children versus adolescents. The only significant study characteristic that was associated with a higher effect size was the use of a cross‐over design versus parallel group design.

Dihydroergotamine

There is insufficient evidence for oral dihydroergotamine in the treatment of migraine in children or adolescents. We only identified one small cross‐over study, which found that oral dihydroergotamine was not superior to placebo.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Of the 27 randomized controlled trials we identified on migraine symptom relieving medications used in the outpatient setting for children and adolescents, 24 belonged to the triptan class, including almotriptan, eletriptan, naratriptan, rizatriptan, sumatriptan, and zolmitriptan. Pharmaceutical companies sponsored most of the triptan studies (N = 19). We only identified three studies of the most frequently used pain medications (paracetamol and ibuprofen) and none examining other non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or early treatment (Goadsby 2008; Suthisisang 2010). We only identified one study on a combination medication (sumatriptan plus naproxen sodium).

Quality of the evidence

We judged the quality of evidence for the effect of triptans on pain relief to be moderate, having downgraded it due to serious inconsistency in adolescents and imprecision in children (small sample size, few events, and wide confidence intervals. For ibuprofen, we downgraded the quality of the evidence by two levels to low due to very serious imprecision (small sample size, few events, and wide confidence intervals). It is likely that future research will help to tighten the confidence intervals around the effect size of the above medications. More evidence is needed to assess the effect of paracetamol in children and adolescents. Although we identified heterogeneity between the results in the triptan studies, we believe that further research is unlikely to change the direction of the effect.

Potential biases in the review process

The reviewers searched the indexed and gray literature extensively to identify all published and unpublished studies of medications used in the treatment of migraine in children and adolescents. Pharmaceutical company clinical trial registries were available for sumatriptan, sumatriptan + naproxen sodium, rizatriptan, and zolmitriptan studies, and we identified some negative trials in these sources. The absence of trial registries for the other medications may bias the identification of other negative trials. The funnel plot examination suggested some potential for publication bias, but the Egger statistical tests for bias were not significant.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A number of similar systematic reviews have been published. The review by Major 2003 of triptan studies in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 years concluded that intranasal sumatriptan was effective, while other oral triptans were not. The American Academy of Neurology Quality Standards Subcommittee and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society have published a practice parameter on the pharmacological treatment of migraine (Lewis 2004). Our conclusions are similar with regard to the evidence for efficacy of ibuprofen in children but differ with regard to the efficacy of paracetamol. The practice parameter also concluded that sumatriptan nasal spray was effective for the acute treatment of migraine in adolescents. Damen 2005 evaluated all randomized controlled trials for the acute treatment of migraine in children and adolescents less than 18 years of age but identified a smaller number of trials (10 studies). The authors performed a meta‐analysis, and concluded there was evidence for the use of ibuprofen, paracetamol, and intranasal sumatriptan. Silver 2008 also included all medications for the acute treatment of migraine in their search, but identified only 11 studies in children and adolescents under 18 years of age. The authors concluded that there was evidence only for the use of ibuprofen and sumatriptan and did not differentiate between oral and intranasal sumatriptan preparations. A meta‐analysis and qualitative review of ibuprofen and paracetamol in adults, adolescents, and children concluded that ibuprofen was at least as efficacious as paracetamol (Pierce 2010). Eiland 2010 recommended the triptan class as an acute treatment option for children and adolescents with migraines, also concluding that there was evidence to recommend sumatriptan and zolmitriptan nasal sprays as well as rizatriptan or almotriptan tablets over the other triptans. Vollono 2011 examined 11 studies and concluded that triptans are an important option in the symptomatic treatment of childhood and adolescent migraine. Individually, they found that zolmitriptan and rizatriptan were superior to placebo in most studies, and almotriptan was well tolerated. Toldo 2012 recommended paracetamol and ibuprofen as first line treatments for migraine in children and adolescents. The triptans were deemed safe, and the authors concluded that sumatriptan nasal spray was more effective than placebo and that zolmitriptan nasal spray and rizatriptan tablets were likely effective. Wöber‐Bingöl 2013 examined 14 studies on triptans in adolescents and 6 studies in children and concluded that evidence for the acute pharmacological treatment of migraine in children was poor, but evidence for adolescents was better, albeit still limited. The authors outlined that sumatriptan nasal spray and zolmitriptan nasal spray were approved for adolescents in Europe; while in the United States almotriptan can be used for adolescents and rizatriptan is approved for patients aged 6 to 17 years. The combination of sumatriptan and naproxen sodium in adolescents has also since been approved for use in adolescents in the United States. Bonfert 2013 included 33 studies examining acute and preventive treatment for migraine and tension‐type headaches. The reviewers did not conduct a meta‐analysis but reviewed the individual studies, concluding that ibuprofen and paracetamol should be considered first and second line therapies for the acute treatment of migraine in children and adolescents, with almotriptan and rizatriptan as suitable third‐line agents.

Finally, a recent review identified only seven studies in adolescents aged 12 to 17 years and concluded that enrichment designs significantly reduced placebo response (Sun 2013). Our review includes a higher number of studies (N = 27), including negative studies published only in pharmaceutical‐industry sponsored trial registries. We draw similar conclusions with regard to the benefit and safety of ibuprofen in treating children and adolescents with migraine. As with previous reviews, the low cost, broad availability, and safety may make ibuprofen a preferred first choice. We differ however in our conclusion that there is insufficient evidence to recommend paracetamol. In general our conclusions are similar with regard to the triptans as a class of medication being effective in the treatment of children and adolescents with migraine. We differ in that we found insufficient evidence to recommend one triptan over the others in our meta‐analysis and sub‐group analyses. While rizatriptan, sumatriptan, and zolmitriptan were statistically superior to placebo as subgroups, the overall test for subgroup heterogeneity was not significant. In our meta‐analysis, we combined the studies of triptan medications irrespective of route of delivery and dosage.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We found low quality evidence from two small studies that ibuprofen appears to improve pain relief in children with migraine. We have only limited information on adverse events in the trials included in this review. There is insufficient evidence in favor of paracetamol. We did not identify evidence regarding early treatment, the use of other NSAIDs, or the combination of these analgesics with other medications (e.g. metoclopramide, caffeine) in children or adolescents.

For children and adolescents with migraine, triptans appear to be effective in the acute treatment of migraine. Sumatriptan plus naproxen sodium is effective in adolescents, but we did not find any studies in children. Triptans are generally safe but carry an increased risk of minor (non‐serious) adverse events.

For clinicians, the choice of triptan medication may be guided by factors such as patient preference, route of delivery, or palatability. A parent who responds well to one of the medications may be more likely to request that medication for their child. More than half of the triptan studies in children and adolescents were of sumatriptan, and this medication serves as the reference drug in this class. The choice of triptan may also be based on local availability, drug cost reimbursement, and regulatory approval. We found inconsistent evidence in our subgroup analysis of the intranasal versus oral triptan preparations, but patients may prefer one route over the other (e.g. intranasal if significant vomiting or oral if patient has chronic rhinitis).

For policymakers and funders, the triptan class of medications, as well as sumatriptan in combination with naproxen sodium, are suitable options for children and adolescents with migraine. One or more of these medications should be made available in situations where ibuprofen has failed to provide pain freedom or headache relief.

Implications for research.

General

Future studies should separate the childhood and adolescent age groups to enable separate meta‐analyses of these groups. More studies of simple analgesics commonly used in the treatment of migraine like paracetamol and ibuprofen, other NSAIDs, or head to head comparisons are warranted.

Design

Studies employing a cross‐over design were associated with significantly higher effect size estimates. Similar findings have been reported previously (Lathyris 2007). This may have been due to inadequate blinding in cross‐over studies or higher effect estimates due to the smaller sample size. Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine advocate the use of either cross‐over or parallel design (Tfelt‐Hansen 2012).

Measurement (endpoints)

Pain freedom as an outcome measure demonstrated low heterogeneity between studies and may be most suitable as a primary outcome measure. Data on other outcome measures (e.g. nausea, headache relief, etc.) should also be collected, as described in the guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine (Tfelt‐Hansen 2012).

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 October 2020 | Review declared as stable | See Published notes. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2005 Review first published: Issue 4, 2016

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 October 2018 | Review declared as stable | See Published notes. |

| 1 September 2010 | Feedback has been incorporated | Incorporated feedback from Editorial review and updated search. |

| 15 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Notes

This systematic review has not previously been published in full form. The data have been presented at the American Headache Society Annual Scientific meeting.

Assessed for updating in 2018

A full search was performed in February 2018 and after screening the results the authors did not identify any potentially relevant studies. At October 2018, this review has been stabilised following discussion with the authors and editors. New treatments for migraine are anticipated, and we will update the review if new evidence likely to change the conclusions is published, or if standards change substantially which necessitate major revisions.

Assessed for updating in 2020

At October 2020 we are not aware of any potentially relevant studies likely to change the conclusions, although this is an active area of research and new studies are expected in the next two to three years. Following discussion with the authors and editors, this review has now been stabilised and will be reassessed for updating in two years. If appropriate we will update the review sooner if new evidence likely to change the conclusions is published, or if standards change substantially which necessitates major revisions.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Lawrence Richer wishes to thank Dr. Brian Rowe for mentoring his Master of Science in Clinical Epidemiology training and thesis preparation.

Cochrane Review Group funding acknowledgement: The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of the Cochrane PaPaS Group. Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, National Health Service (NHS) or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Complete Search Strategy

LITERATURE SEARCH—Drugs for the acute treatment of migraine in children and adolescents

| Database | 2008 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2016 | Total | ||||||

| Number retrieved | After duplicates removed | Number retrieved | After duplicates removed | Number retrieved | After duplicates removed | Number retrieved | After duplicates removed | Number retrieved | After duplicates removed | Number retrieved | After duplicates removed | |

| MEDLINE | 2844 | 2742 | 639 | 616 | 90 | 75 | — | — | 326 | 231 | 3899 | 3664 |

| MEDLINE In‐Process | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 16 | 14 | — | — | — | — | 74 | 72 |

| CCRT | 153 | 126 | 153 | 126 | 10 | 2 | — | — | — | — | 316 | 254 |

| CDSR DARE | 664 | 650 | 664 | 650 | 324 | 169 | — | — | — | — | 1652 | 1469 |

| IPA | 109 | 27 | 40 | 10 | 7 | 4 | — | — | — | — | 156 | 41 |

| PsycINFO | 255 | 147 | 147 | 85 | 5 | 3 | — | — | — | — | 407 | 235 |

| EMBASE | 6357 | 5548 | 2884 | 2517 | 508 | 412 | 794 | 787 | 626 | 516 | 11,169 | 9780 |

| CINAHL | 712 | 190 | 263 | 70 | 31 | 21 | — | — | — | — | 1006 | 281 |