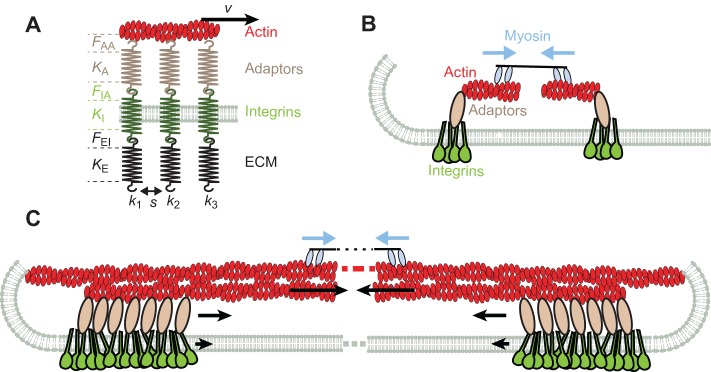

Fig. 2.

Summary of mechanical factors in integrin adhesions. (A) Role of stiffness. Whether and where a single connection between integrins and actin unfolds or breaks under force will depend on the stiffness of the ECM molecule (KE), integrin (KI), and adaptor protein (KA), and the maximum force that can be withstood by the ECM–integrin bond (FEI), the integrin–adaptor bond (FIA) and the adaptor–actin bond (FAA). These stiffness values will generally increase with protein stretching, and change after unfolding or unbinding events. To our knowledge, integrin stiffness (KI) or possible unfolding have not been described. The total stiffness of the chain (k1) will be determined by the softest element in it, and will operate in parallel with other chains in the cluster (k2, k3). The rearward speed v of the actin layer, multiplied by k1, will provide the rate of force loading in the chain, which will affect both individual rupture forces (FEI, FIA, and FAA) and the effectiveness with which the different chains in the cluster cooperate to withstand force. The spacing between integrins (s) will also affect cluster formation. (B) Nascent focal adhesions. In nascent adhesions, adaptor proteins mediate the formation of initial integrin clusters {containing talin, kindlin and PtdIns(4,5)P2}, and might promote actin polymerization from clusters (formins). Myosin II filaments exert local contractile forces between filaments (blue arrows). (C) Focal adhesion maturation. As adhesions mature and grow, they connect to actin fibers moving rearward towards the cell center due to global myosin contractility (blue arrows). Rearward moving actin pulls on bound adaptor proteins, which in turn pull on integrins. Because of transient stick-slip bonds, rearward speeds are reduced with respect to actin to a certain extent in adaptor proteins, and even further in integrins (black arrows).