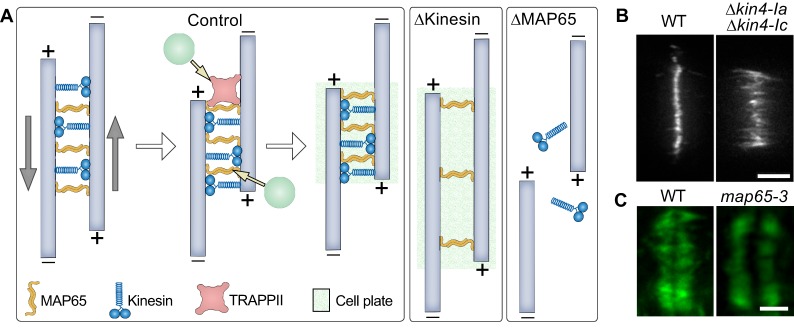

Fig. 3.

Mechanics of the phragmoplast midzone establishment. (A) MAP65 (orange) bundles anti-parallel microtubules (pale blue) in the midzone. Anterograde kinesins (blue) bind to anti-parallel microtubules and slide them apart in opposite directions, as shown by gray arrows. Eventually, the thickness of the midzone is determined by the balance of forces generated by kinesin movements and the affinity of MAP65 for microtubules. MAP65 interacts with the tethering complex TRAPPII. Tethering complexes can initiate cell plate assembly by recruiting vesicles (green circles) to the midzone. In the absence of kinesins (ΔKinesin), both the midzone and cell plate are wider. In the absence of MAP65 (ΔMAP65), kinesins slide microtubules away from each other. Consequently, cell plate formation is abrogated. (B) Example picture of the localization of MAP65a-citrine in Physcomytrella caulonemal tip cell. Reprinted from de Keijzer et al., 2017, with permission from Elsevier. Double knockout of Kin4-Ia and Kin4-Ic results in wider microtubule overlap as evident by MAP65a–citrine localization in living cells. (C) Example picture of how loss of MAP65-3 activity (Arabidopsis ple-6 allele) leads to a wider phragmoplast midzone. Reprinted from Muller et al., 2004, with permission from Elsevier. Microtubules were immunostained with anti-tubulin antibody (green). WT, wild type. Scale bars: 5 μm (B), 2 µm (C).