Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of traumatic dental injuries (TDIs) in the anterior teeth among children attending paramilitary and nonparamilitary schools in Benin City, Nigeria.

Materials and Methods:

A multistage sampling technique was used to select children aged 8–12 years with a previous history of trauma to the orofacial region. A self-administered questionnaire was then applied, and each participant was examined clinically. Data collected included demographic characteristics, etiology and place of injury, affected teeth, type of dental injury, lip competence, and overjet values. Analysis of data was done with the SPSS version 21.0 software. Pearson's Chi-squared test was used to determine the association between variables and odds ratio. Statistical significance was determined at P < 0.05.

Results:

A total number of 1352 children (mean age: 9.89 ± 1.4 years) were examined and 154 (11.4%) had a previous history of TDI. The prevalence among respondents in the paramilitary schools was 84 (6.2%) and those in nonparamilitary schools 70 (5.2%). Falls and play was the most common cause of TDI and was higher in children in paramilitary schools. Ellis Class I was the most prevalent type of injury in 91 (59.1%), tooth number 21 was the most traumatized, and the school environment was the most common place. Of the total number of respondents with TDI, the relationship between etiology with age, lip competence, and overjet was statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

The prevalence of TDI among the study participants was 11.4% and more in the paramilitary schools than the nonparamilitary.

Keywords: Dental trauma, nonparamilitary schools, paramilitary, traumatisme dentaire, écoles non paramilitaires, paramilitaires

Résumé

Objectif:

L’objectif de cette étude était de déterminer la prévalence des traumatismes dentaires traumatiques (TDI) dans les dents antérieures chez les enfants. fréquentant des écoles paramilitaires et non paramilitaires à Benin City, au Nigeria.

Matériels et méthodes:

Une technique d’échantillonnage en plusieurs étapes a été utilisée. utilisé pour sélectionner les enfants âgés de 8 à 12 ans ayant des antécédents de traumatisme dans la région orofaciale. Un questionnaire auto-administré a ensuite été appliqué, et chaque participant a été examiné cliniquement. Les données collectées comprenaient les caractéristiques démographiques, l’étiologie et le lieu de la blessure, dents affectées, type de lésion dentaire, compétence labiale et valeurs overjet. L’analyse des données a été réalisée avec le logiciel SPSS version 21.0. Le test du chi carré de Pearson a été utilisé pour déterminer l’association entre variables et odds ratio. La signification statistique a été déterminée à p <0,05.

Résultats:

Un nombre total de 1352 enfants (âge moyen: 9,89 ± 1,4 ans) ont été examinés et 154 (11,4%) avaient des antécédents de TDI. La prévalence parmi les répondants des écoles paramilitaires était de 84 (6,2%) et ceux des écoles non paramilitaires de 70 (5,2%). Des chutes et le jeu était la cause la plus Iréquente de TDI et était plus élevé chez les enfants dans les écoles paramilitaires. Ellis Classe I était le type le plus répandu de blessures chez 91 personnes (59,1%), la dent numéro 21 était la plus traumatisée et le milieu scolaire le plus fréquent. Du nombre total des répondants avec TDI, la relation entre l’étiologie, l’âge, la compétence labiale et l’overjet était statistiquement significative (p <0,05).

Conclusion:

La prévalence du TDI chez les participants à l’étude était de 11,4% et plus dans les écoles paramilitaires que dans les écoles non paramilitaires.

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic dental injury (TDI) is described as a lesion of variable extension, intensity, and severity caused by forces acting on teeth due to falls, fights, traffic accidents, collision against objects or people, and parafunction and/or as a result of an assault.[1,2] It has a great impact on the quality of life, affecting children physically, esthetically, and psychologically.[2] Oral injuries are most frequent during the first 10 years of life, decreasing gradually with age, and are very rare after the age of 30 years. On the contrary, nonoral injuries are most frequently seen in adolescents and young adults and are common throughout the life.[2,3] Although the oral region comprises an approximate area of 1% of the total body, it accounts for about 5% of all injuries for which patients seek treatment.[2]

Oral injuries are more frequent in children and young adolescents who are in school, which may be normal or special schools.[4,5] Paramilitary schools are special schools affiliated with the army, navy, or air force but have the same curriculum as normal schools.[4] However, one special aspect of the paramilitary school is the discipline they inculcate in their students, most of which might not be found in private or public schools. One other thing about these schools is that most of them are located within the barracks.[4] While these studies[4,5] found a higher prevalence in the incidence of lacerations followed by fracture of the teeth, studies on children in normal schools revealed a higher incidence of fracture of the teeth.[6,7,8]

Most studies on TDI were observed to be in children in normal schools[5,6,7,8] with a high prevalence of fractured anterior teeth in children with the maxillary incisors being more involved.[7] Other studies[8] determined a prevalence of dental injuries in children with an incisor overjet of >6 mm as well as incompetent lips. This was, however, not an observed factor or etiologic agent in those receiving military training from other studies.[2,3] Studies also showed that an increase in age was also a factor in the prevalence and causes of TDI to the permanent dentition, with a highly significant association between TDI and occupation type.[2,9,10] Gender has also been found to be a significant factor[11] in studies on TDIs with males being more prone to injuries than female.

Most studies on TDI, however, did not categorize school type, and with an increase in conflict worldwide, more paramilitary schools are being established for training.[5] The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of TDIs in the anterior teeth among children attending paramilitary and nonparamilitary schools in Benin City, Nigeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A list of schools was obtained from the State Ministry of Education and divided into two groups (normal schools and paramilitary schools). A multistage sampling technique was then employed in each group to select schools. All children who fell within the selected age range of 8–12-years were included within the pool. A convenience sampling method was now used to select the participants from each pool by asking a general question, i.e., “To simply identify by raising up their hands, if they have had any form of injury to their mouth/teeth.” All those who had a previous history of trauma to their orofacial region were then separated from the pool. A self-administered questionnaire was applied and thereafter examined clinically. A total sample size of 1352 children was now obtained.

Exclusion criteria included children below 8 years and over 12 years in paramilitary and nonparamilitary schools in Benin City, those from whom informed assent/consent could not be sought, and those indisposed as at the time of this study. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee of the College of Medical Sciences, University of Benin, Benin City. Informed consent was obtained from head teachers of the schools and the needed assent sought from the study participants.

Data collection

Data collection was done through clinical examination, and a self-administered questionnaire which was anonymous with no identifiers was used to elicit their demographic characteristics, cause, and place of injury. The clinical examination of the study participants was done by a single calibrated examiner (PU), using a mouth mirror and the community periodontal index probe. Information was recorded on teeth affected, type of injury, lip competence, and overjet values. Ellis and Davey's (1970)[12] classification was used for recording injuries. However, Type VI (root fracture) was not recorded as dental radiographs were not available for diagnosis in the in-school field condition.

Lip examination was done by visual inspection of the lip as the participant approached the examination chair without participants' awareness and was recorded as adequate if the lips covered the maxillary incisor at rest position and as inadequate if majority of the crown height was exposed.[8]

Overjet measurement was made with the teeth in centric occlusion; the distance from the labial incisal edge of the most prominent maxillary incisor to the labial surface of the corresponding mandibular incisor was measured using the community periodontal index probe, as described in the 1997 World Health Organization basic oral health survey guidelines.[12]

The skeletal pattern was assessed with the participant head in a neutral position, sitting upright, and relaxed. It was done by placement of the index and middle fingers at the soft tissue Point A and Point B, respectively. For Class I skeletal pattern, the hand is at the same level; for Class II skeletal pattern, the hand points upward, and for Class III skeletal pattern, the hand points downward.[8]

Data analysis

Data generated from the study were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0 software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Pearson's Chi-squared test was used to test for the association between variables and odds ratio. The level of statistical significance was P < 0.05.

RESULTS

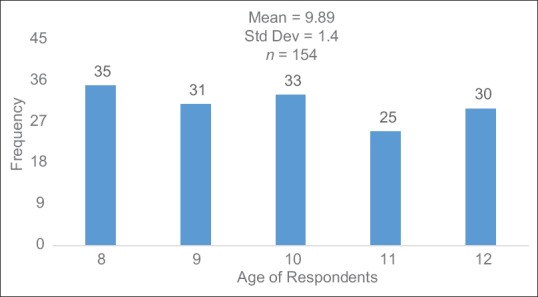

A prevalence of TDI was seen in 154 (11.4%) out of a total number of 1352 schoolchildren examined. Paramilitary schools recorded a prevalence of 84 (6.2%), while nonparamilitary schools showed a prevalence of 70 (5.2%). A mean age of 9.89 ± 1.4 years was identified in TDI. The 8 and 10 year old children in this study demonstrated the peak of traumatic injuries to their anterior teeth in 35 (22.7%) and 33 (21.4%) respectively [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution of age of all the respondents with traumatic dental injuries

The school environment was the most common place for TDI in 88 (57.1%), followed by the home in 64 (41.6%) and other environments in 2 (1.3%).

The prevalence of TDI among the respondents in the paramilitary schools was 84 (12.2%) and those in nonparamilitary schools 70 (10.5%). Most of the respondents in paramilitary and nonparamilitary schools were 49 (58.3%) and 41 (58.6%) males, respectively. The most prevalent age with TDI in the paramilitary school was 10 years in 21 (25.0%) and 8 years in normal schools in 30%. Other demographic characteristics are seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents in paramilitary and nonparamilitary schools with traumatic dental injury

| Variable | Frequency (%) |

Total (154), n (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paramilitary schools (84) | Nonparamilitary schools (70) | |||

| Age | ||||

| 8.00 | 14 (16.7) | 21 (30.0) | 35 (22.7) | 0.111 |

| 9.00 | 16 (19.0) | 15 (21.4) | 31 (20.2) | |

| 10.00 | 21 (25.0) | 12 (17.1) | 33 (21.4) | |

| 11.00 | 12 (14.3) | 13 (18.6) | 25 (16.2) | |

| 12.00 | 21 (25.0) | 9 (12.9) | 30 (19.5) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 49 (58.3) | 41 (58.6) | 90 (58.4) | 0.976 |

| Female | 35 (41.7) | 29 (41.4) | 64 (41.6) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Edo indigenes | 62 (77.5) | 47 (67.1) | 109 (70.8) | 0.365 |

| Non-Edo indigenes | 22 (22.5) | 23 (32.9) | 45 (29.2) | |

| Religion | ||||

| Christian | 81 (96.4) | 68 (97.1) | 149 (96.8) | 0.0803 |

| Islam | 3 (3.6) | 2 (2.9) | 5 (3.2) | |

| Class | ||||

| Primary 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.6) | 0.081 |

| Primary 2 | 3 (3.6) | 3 (4.3) | 6 (3.9) | |

| Primary 3 | 12 (14.3) | 16 (22.9) | 28 (18.2) | |

| Primary 4 | 23 (27.3) | 17 (24.3) | 40 (26.0) | |

| Primary 5 | 41 (48.8) | 25 (35.7) | 66 (42.9) | |

| Primary 6 | 5 (6.0) | 8 (11.4) | 13 (8.4) | |

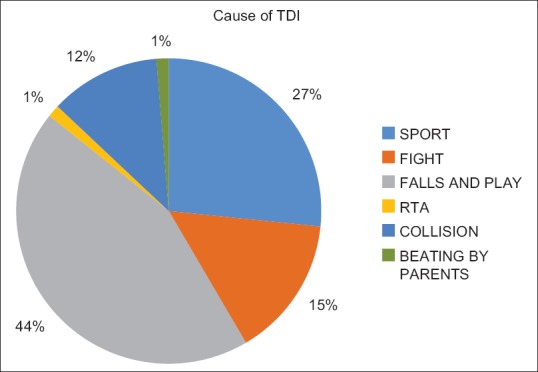

Figure 2 demonstrates the distribution of TDI according to the etiology with falls and play as the most common cause of TDI in 68 (44.2%) and least from beating and road traffic accident in 2 (1.3%).

Figure 2.

Distribution of traumatic dental injury according to the etiology

Table 2 shows the frequency distribution of TDI according to the Ellis classification. Class I was highest in 91 (59.1%) and least in Ellis Class III in 2 (1.3%).

Table 2.

Frequency distribution of traumatic dental injury (n=154)

| Categories of TDI | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Ellis Class I | 91 (59.1) |

| Ellis Class II | 29 (18.8) |

| Ellis Class III | 2 (1.3) |

| Ellis Class IV | 8 (5.2) |

| Ellis Class V | 16 (10.4) |

| Ellis Class VII | 8 (5.2) |

TDI=Traumatic dental injury

The most traumatized anterior tooth was 21 in 83 (53.9%) followed by tooth number 11 in 42 (27.3%) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Frequency distribution of traumatized teeth (n=154)

| Traumatized dentition (FDI) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| 11 | 42 (27.3) |

| 12 | 8 (5.2) |

| 21 | 83 (53.9) |

| 22 | 16 (10.4) |

| 32 | 1 (0.6) |

| 33 | 2 (1.3) |

| 41 | 2 (1.3) |

FDI=Fédération Dentaire Internationale (International Dental Association)

Table 4 shows the frequency distribution of lip competence, skeletal pattern, and overjet with a higher number 132 (85.7%) demonstrating lip competency. Class I skeletal pattern was highest in 151 (98.1%) and overjet values of ≤3 mm in 127 (82.5%).

Table 4.

Frequency distribution of lip competence, skeletal pattern, and overjet values of the respondents with traumatic dental injury (n=154)

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Lip competence | |

| Competent lip | 132 (85.7) |

| Incompetent lip | 22 (14.3) |

| Skeletal pattern | |

| I | 151 (98.1) |

| II | 2 (1.3) |

| III | 1 (0.6) |

| Overjet range (mm) | |

| ≤3 | 127 (82.5) |

| >3 | 27 (17.5) |

Table 5 demonstrates the relationship between the sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents and the etiologic factors implicated in TDI. A significant relationship was seen between the age of the respondents and TDI (P < 0.05).

Table 5.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents and cause of traumatic dental injury

| Variable | Etiology of TDI |

P | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sports, n (%) | Fights, n (%) | Falls and play, n (%) | RTA, n (%) | Collision, n (%) | Beating by parent, n (%) | Total 100% | ||

| Age | ||||||||

| 8.00 | 3 (8.6) | 4 (11.4) | 16 (45.7) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (28.6) | 2 (5.7) | 35 | 0.023* |

| 9.00 | 10 (32.3) | 7 (22.6) | 11 (35.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (9.7) | 0 (0.0) | 31 | |

| 10.00 | 8 (24.2) | 4 (12.1) | 19 (57.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.1) | 0 (0.0) | 33 | |

| 11.00 | 8 (32.0) | 3 (12.0) | 10 (40.0) | 1 (4.0) | 3 (12.0) | 0 (0.0) | 25 | |

| 12.00 | 12 (40.0) | 5 (16.7) | 12 (40.0) | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 30 | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 24 (26.7) | 16 (17.8) | 38 (42.2) | 1 (1.1) | 9 (10.0) | 2 (2.2) | 90 | 0.644 |

| Female | 17 (26.6) | 7 (10.9) | 30 (46.9) | 1 (1.6) | 9 (14.1) | 0 (0.0) | 64 | |

| School | ||||||||

| Paramilitary | 20 (23.8) | 15 (17.9) | 40 (47.6) | 2 (2.4) | 7 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 84 | 0.159 |

| Nonparamilitary | 21 (30.0) | 8 (11.4) | 28 (40.0) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (15.7) | 2 (2.9) | 70 | |

| Class | ||||||||

| Primary 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 0.000* |

| Primary 2 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (33.3) | 6 | |

| Primary 3 | 5 (17.9) | 3 (10.7) | 11 (39.3) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (32.1) | 0 (0.0) | 28 | |

| Primary 4 | 7 (17.5) | 6 (15.0) | 22 (55.0) | 1 (2.5) | 4 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 40 | |

| Primary 5 | 24 (36.4) | 10 (15.2) | 26 (39.4) | 1 (1.5) | 5 (7.6) | 0 (0.0) | 66 | |

| Primary 6 | 5 (38.5) | 3 (23.1) | 5 (38.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 13 | |

*Significant (P<0.05). TDI=Traumatic dental injury, RTA=Road traffic accidents

Table 6 demonstrates the relationship between the predisposing factors and TDI with lip competence, skeletal pattern, and overjet values. A highly significant relationship was seen between lip competence and overjet values (P < 0.05).

Table 6.

Relationship between the predisposing factors and traumatic dental injury with the lip

| Competence, skeletal pattern, and overjet values | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Cause of TDI |

P | ||||||

| Sport, n (%) | Fight, n (%) | Falls and play, n (%) | RTA, n (%) | Collision, n (%) | Beating by parents, n (%) | Total 100% | ||

| Lip competence | ||||||||

| Competent lip | 30 (22.7) | 22 (16.7) | 63 (47.7) | 2 (1.5) | 15 (11.4) | 0 (0.0) | 132 | 0.000* |

| Incompetent lip | 11 (50.0) | 1 (4.5) | 5 (22.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (13.6) | 2 (9.1) | 22 | |

| Skeletal pattern | ||||||||

| I | 41 (27.2) | 23 (15.2) | 65 (43.0) | 2 (1.3) | 18 (11.9) | 2 (1.3) | 151 | 0.953 |

| II | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 | |

| III | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 | |

| Overjet (mm) | ||||||||

| ≤3 | 29 (22.8) | 22 (17.3) | 59 (46.5) | 2 (1.6) | 15 (11.8) | 0 (0.0) | 127 | 0.004* |

| >3 | 12 (44.4) | 1 (3.7) | 9 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (11.1) | 2 (7.4) | 27 | |

*Significant (P<0.05). TDI=Traumatic dental injury, RTA=Road traffic accidents

DISCUSSION

This study recorded a prevalence of TDIs in 11.4%. Although children in paramilitary schools had a higher number of TDIs than children in nonparamilitary schools, the difference was not statistically significant in this study. Other studies on TDI[13,14] in children with special needs and those adolescents attending military schools[4,5] also demonstrated a difference on the average but with no statistical significance.

While prevalences of TDI from other Nigerian studies ranged from 6.5% to 19.5%,[7,8,9,10,15] other studies from Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and America revealed a prevalence of 4%–58%.[16,17,18,19] These results demonstrate that TDIs have a wide prevalence based on the study type. While this study compared paramilitary and nonparamilitary schools, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of TDI which is in agreement with the results of other comparative studies in other groups.[4,5,13,14]

This study determined that males in both schools were at a greater risk of TDIs when compared to females. Although this was not statistically significant in this study, this finding was observed in previous studies,[6,18,19] where a higher prevalence was seen in males. Studies have shown that males participate more actively in sporting activities,[4,5,6] preferably the more aggressive type of games,[5] demonstrate more violent behavior, and engage more often in contact sports.[18,19] On the contrary, other studies have indicated an increasing trend of dental trauma among females due to their increasing participation in sports or activities previously practiced by males only.[4,5,19,20]

In this study, the most common cause of trauma to the anterior teeth was due to falls and play. This study also determined that more males were involved in sports and fight while more females were involved in falls- and collision-related TDI. More participants in the paramilitary schools were involved in fights and falls while more participants in nonparamilitary schools were involved in sports- and collision-related TDI. This finding is in agreement with other studies,[9,13,14,21,22,23,24] where falls were a major factor in TDI. Other studies that compared military and nonmilitary TDIs[4,5] also determined that falls were the major cause in nonmilitary incidents.

This current study showed a highly significant difference between lip competence and the degree of overjet in the etiology of TDIs. This is in agreement with another study,[8] however, in contrast with the result from other studies on children in special schools which showed that there was no significant difference or correlation between the number of injuries and the size of the overjet.[14] Furthermore, their study[14] determined that excessive overjet, lip competency, or facial pattern did not increase the prevalence of trauma.

This study reported enamel fracture (Ellis Class I) as the most common type of injury and accounted for 59.1% of the total. This is in agreement with findings from another study[4,5] that compared military and nonmilitary dental injuries, where a high prevalence of 73% was observed.[4] This is at variance with the results of TDI in a group of children with cerebral palsy where a 30% prevalence was observed.[13]

The next most common type of dental injury recorded in this study was those involving the enamel and dentin (Ellis Class II). This study also showed the maxillary central incisors as the most commonly involved teeth. These findings are in accordance with previous studies,[13,15,21,22,23,24,25,26] and the reason adduced was that the position of these teeth makes them more susceptible to trauma as seen in other studies.[21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]

This study demonstrated that the place of common occurrence of TDIs was the school environment followed by home. This finding is in agreement with a previous study[4,5,23] although other studies have reported that the home was the most prevalent place for TDI.[9,21,26,27] This could be due to the fact that children tend to play unsupervised during recess periods in school. Rough play as a result of the excitement of closing and being freed from classroom restrictions could also be a factor implicated in traumatic injuries to the anterior teeth.[10]

Age and class were found to have a significant relationship in TDI from this study. There was an increase in TDI from Primary 4–6 due to fights and sporting activities but a decrease in falls from Primary 3 through to Primary 1. This is in agreement with other studies where older children are more prone to TDI.[6,7,9,10,16]

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of TDI in this study is 11.4%. The prevalence of TDI is higher on the average in the paramilitary schools than in the nonparamilitary, but there is no statistical difference. Older children accounted for more TDI than younger children. A highly significant relationship exists between an increased overjet, lip competency, and skeletal pattern.

Recommendations

Monitoring of schoolchildren during play and sporting activities, especially during break and immediately after the school

Making the play areas less traumatic with reduction of potentially dangerous hard surfaces

Raise awareness among the schoolchildren on need to promptly report rough and violent activities.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Losso EM, Tavares MC, Bertoli FM, Baratto-Filho F. Trauma in the deciduous dentition. Rev Sul Bras Odontol. 2011;8:e1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersson EE, Andersson L, Sörensen S. Traumatic oral vs. non-oral injuries. Swed Dent J. 1997;21:55–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glendor U, Andersson L. Public health aspects of oral diseases and disorders: Dental trauma. In: Pine C, Harris R, editors. Community Oral Health. London: Quintessence Publishing; 2007. pp. 203–11. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agbor AM, Nossi AF, Azodo CC, Kamga CL, Zing S. Training-related maxillofacial injuries in Cameroon military. SRM J Res Dent Sci. 2016;7:6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motamedi MH, Sagafinia M, Famouri-Hosseinizadeh M. Oral and maxillofacial injuries in civilians during training at military garrisons: Prevalence and causes. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114:49–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hegde R, Agrawal G. Prevalence of traumatic dental injuries to the permanent anterior teeth among 9- to 14-year-old schoolchildren of Navi Mumbai (Kharghar-Belapur Region), India. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2017;10:177–82. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agbelusi GA, Jeboda SO. Traumatic fracture of anterior teeth in 12-year old Nigerian children. Odontostomatol Trop. 2005;28:23–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otuyemi OD. Traumatic anterior dental injuries related to incisor overjet and lip competence in 12-year-old Nigerian children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1994;4:81–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263x.1994.tb00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adekoya-Sofowora CA, Adesina OA, Nasir WO, Oginni AO, Ugboko VI. Prevalence and causes of fractured permanent incisors in 12-year-old suburban Nigerian schoolchildren. Dent Traumatol. 2009;25:314–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2008.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taiwo OO, Jalo HP. Dental injuries in 12-year old Nigerian students. Dent Traumatol. 2011;27:230–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2011.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baldava P, Anup N. Risk factors for traumatic dental injuries in an adolescent male population in India. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2007;8:35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Oral Health Survey Basic Methods. 4th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.dos Santos MT, Souza CB. Traumatic dental injuries in individuals with cerebral palsy. Dent Traumatol. 2009;25:290–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2009.00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Acharya BS, Ritwik P, Fenton SJ, Velasquez GM, Hagan J. Dental trauma in children and adolescents with mental and physical disabilities. Tex Dent J. 2010;127:1265–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adekoya-Sofowora C, Bruimah R, Ogunbodede E. Traumatic Dental Injuries Experience in Suburban Nigerian Adolescents. The Internet J Dent Sci. 2004;3:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glendor U. Epidemiology of traumatic dental injuries – A 12 year review of the literature. Dent Traumatol. 2008;24:603–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2008.00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altun C, Ozen B, Esenlik E, Guven G, Gürbüz T, Acikel C, et al. Traumatic injuries to permanent teeth in Turkish children, Ankara. Dent Traumatol. 2009;25:309–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2009.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schatz JP, Hakeberg M, Ostini E, Kiliaridis S. Prevalence of traumatic injuries to permanent dentition and its association with overjet in a Swiss child population. Dent Traumatol. 2013;29:110–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2012.01150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel MC, Sujan SG. The prevalence of traumatic dental injuries to permanent anterior teeth and its relation with predisposing risk factors among 8-13 years school children of Vadodara city: An epidemiological study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2012;30:151–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.99992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costa AM, Maia S, Cruz GL, Rontani RM. Prevalence of dental trauma among children treated in the pediatric dentistry clinic of the state university of Amazonas. Rev Sul Bras Odontol. 2011;8:425–30. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naidoo S, Sheiham A, Tsakos G. Traumatic dental injuries of permanent incisors in 11- to 13-year-old South African schoolchildren. Dent Traumatol. 2009;25:224–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2008.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ain TS, Lingesha Telgi R, Sultan S, Tangade P, Ravishankar Telgi C, Tirth A, et al. Prevalence of traumatic dental injuries to anterior teeth of 12-year-old school children in Kashmir, India. Arch Trauma Res. 2016;5:e24596. doi: 10.5812/atr.24596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garg K, Kalra N, Tyagi R, Khatri A, Panwar G. An appraisal of the prevalence and attributes of traumatic dental injuries in the permanent anterior teeth among 7-14-year-old school children of North East Delhi. Contemp Clin Dent. 2017;8:218–24. doi: 10.4103/ccd.ccd_133_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravishankar TL, Kumar MA, Nagarajappa R, Chaitra TR. Prevalence of traumatic dental injuries to permanent incisors among 12-year-old school children in Davangere, South India. Chin J Dent Res. 2010;13:57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ajayi DM, Abiodun-Solanke IM, Sulaiman AO, Ekhalufoh EF. A retrospective study of traumatic injuries to teeth at a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Niger J Clin Pract. 2012;15:320–5. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.100631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rouhani A, Movahhed T, Ghoddusi J, Mohiti Y, Banihashemi E, Akbari M, et al. Anterior traumatic dental injuries in East Iranian school children: Prevalence and risk factors. Iran Endod J. 2015;10:35–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noori AJ, Al-Obaidi WA. Traumatic dental injuries among primary school children in Sulaimani city, Iraq. Dent Traumatol. 2009;25:442–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2009.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caldas AF, Jr, Burgos ME. A retrospective study of traumatic dental injuries in a Brazilian dental trauma clinic. Dent Traumatol. 2001;17:250–3. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-9657.2001.170602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]