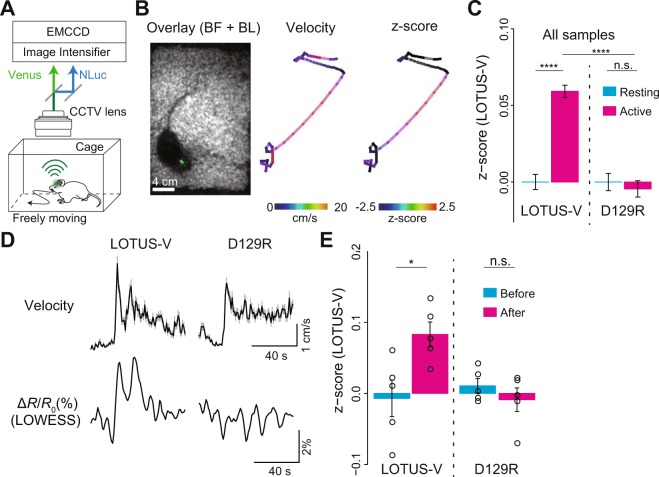

Figure 3.

Imaging of V1 activity in a freely moving mouse using LOTUS-V and an automatic tracking system. (A) Schematic diagram of imaging of a freely moving mouse. The mouse was placed in its home cage and the LOTUS-V bioluminescence was recorded. (B; left) Overlaid image of bright field and LOTUS-V bioluminescence (green). (B; middle and right) Pseudo-colored trajectories of mouse locomotion, indicating velocity (middle) and z-normalized ΔR/R0 (right) (see also Supplementary Videos 1 and 2). (C) Bar plots of z-normalized ΔR/R0 in the resting (<1 cm/s) and active (>1 cm/s) states of freely moving mice (p < 0.0001 for Kruskal-Wallis test with all four categories; resting and active states of LOTUS-V, n = 41005 and 69826 time-points from N = 5 mice; resting and active states of LOTUS-V(D129R), n = 31648 and 34006 from N = 3; p-values shown in the panel were calculated using a Steel-Dwass test). (D) Averaged time series of velocity and LOWESS-smoothed ΔR/R0 at the locomotion onset (LOTUS-V, n = 29 sessions from N = 5 mice; D129R, n = 39 sessions from N = 3 mice). The Granger causality test was applied to determine whether the velocity Granger-causes ΔR/R0 (p < 0.01 and n.s. for LOTUS-V and LOTUS-V(D129R), respectively) (E) The z-normalized ΔR/R0 before (−19 s to 0 s) and after (1 s to 20 s) the locomotion onset. While the circles indicate z-normalized ΔR/R0 at each time point, the bar plots show the average in each category. P-value shown in the panel was calculated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Time bin, 0.1 s (B,C), 1 s (D) and 4 s (E,F); Error bars indicate mean ± standard error; n.s., not significant; *p < 0.05; ****p < 0.0001.