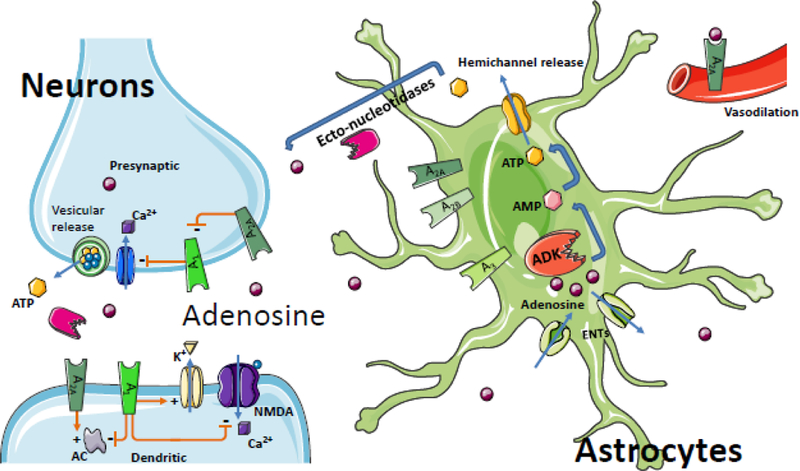

Figure 3.

Adenosine flux between neurons and astrocytes in the brain. Astrocytes serve as a sink for synaptic levels of adenosine. Equilibrative nucleoside transporters (ENTs) normally equilibrate extra- and intracellular adenosine levels; however conditions of increased intracellular ADK drive the influx of adenosine into the cell yielding reduced extracellular levels of adenosine and – consequentially – reduced adenosine receptor activation; ATP, the major source of adenosine, can be released from neurons and astrocytes via vesicles or directly through hemichannels from astrocytes. Adenosine can then be generated through the activity of ectonucleotidases to complete the balance of the ATP / adenosine conversion cycle. The physiological functions of adenosine receptors are more extensively covered in other articles of this Special Issue; briefly, the interactions of select adenosine receptors and metabolite transporters are shown here. Presynaptically, A2A receptors antagonize the inhibitory effect of the A1 receptor on inhibiting calcium (Ca2+) import, which ultimately modulates vesicular release of ATP and glutamate. Postsynaptically, the A1 receptor inhibits calcium import of the N-methyl-D- aspartate receptor (NMDA), increases the conductance of potassium (K+), and inhibits adenylate cyclase (AC); A2A receptors have an opposing stimulation of dendritic AC. A2A receptors also play a role in vasodilation of blood vessels in the brain and periphery. Because the implications of the adenosine system in oligodendrocytes and microglia for epilepsy are largely unknown, those cell-types have been omitted to enhance clarity.