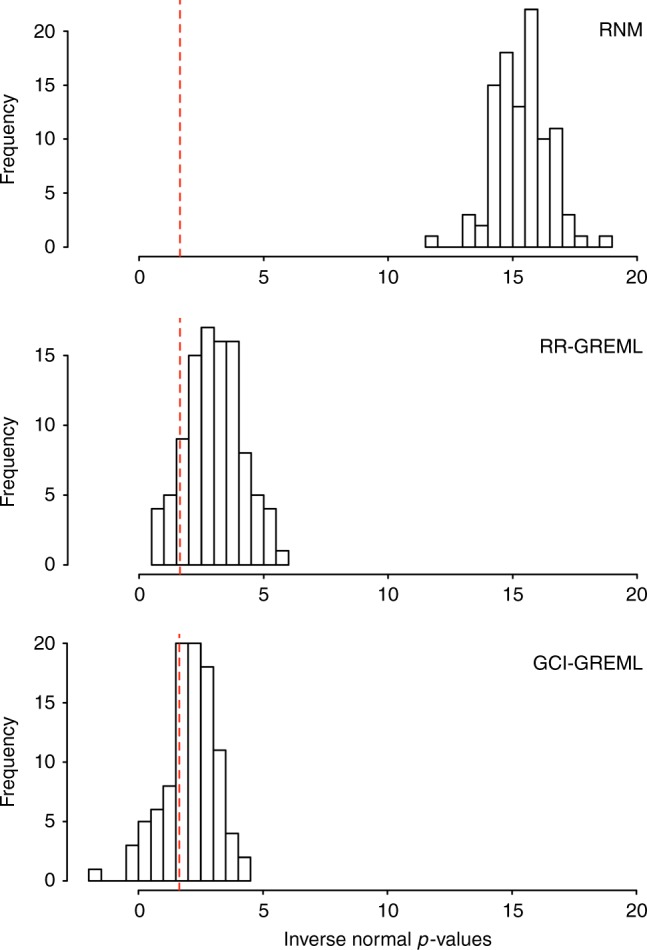

Fig. 3.

RNM has more statistical power than RR-GREML and GCI-GREML. One hundred replicates of data were simulated under a model that assumed the presence of a genotype–covariate interaction. Simulation was based QCed ARIC data consisting 7,263 individuals and 583,058 SNPs. The model is specified as y = α0 + α1 × c + e with c = β + ε, all effects drawn from a multivariate normal distribution, where the variance–covariance structure between α0, β, and α1 (in this order) is and that between e and ε is . For every replicate, each of the three models was fitted to obtain a p-value for the G–C interaction via a comparison between the null (H0) and alternative hypothesis (H1) models using a likelihood ratio test. For RNM, the H0 and H1 models were y = α0 + e and y = α0 + α1 × c + e. For RR-GREML and GCI-GREML, the H0 and H1 models were y = α0 + e and y = α0 + α1 × c + e. In RR-GREML and GCI-GREML, samples were arbitrarily stratified into four different groups according to the covariate levels. RR-GREML explicitly estimate residual variance for each of the four groups whereas GCI-GREML assumes homogeneous residual variance across the four groups and estimates a single residual variance. This figure shows the proportions of significant p-values, i.e., statistical power, for RNM, RR-GREML and GCI-GREML, which are 1, 0.9 and 0.69, respectively. Note that p-values are inverse normal transformed, such that the statistical significance level, i.e., 1.65, shown as dashed lines, is equivalent to the 0.05 level before the transformation