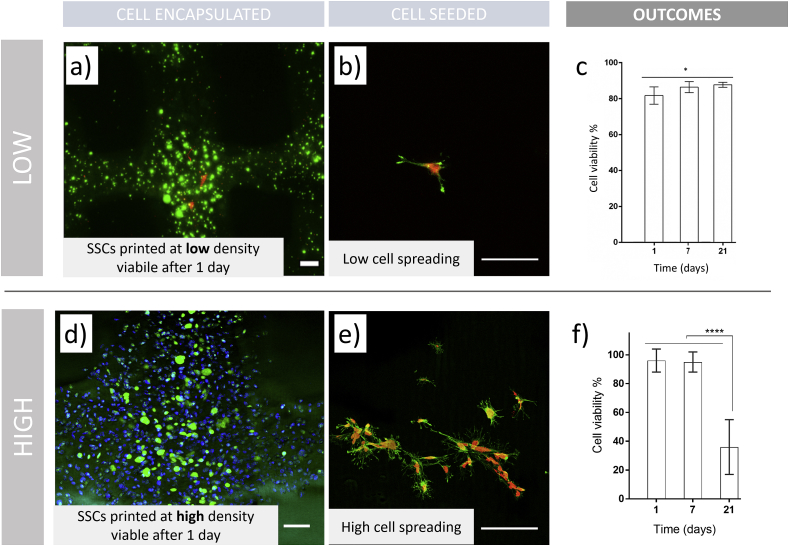

Fig. 6.

Viability of 3D constructs fabricated by cell printing depends on initial cell density. SSCs were encapsulated at (a–c) low density ( ≤1 × 106 cell ml−1) and (d–f) high density (>5 × 106 cell ml−1) GelMA bioinks. (a) Viability of 3D printed GelMA is adapted from Ref. [85] (Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society). Living cells are marked green, dead cells in red. (b) Low cell density seeded on 3D printed GelMA scaffolds. (c) Quantification of viability of 3D printed hMSCs in GelMA is adapted from Ref. [85] (Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society). (d) High cell density is encapsulated and printed in GelMA bioink. Living cells are in green, pre-labelled cells to visualise distribution in blue – from previously employed protocol [31]. (e) Equal density was seeded on top of the 3D printed scaffolds to show visual comparison between different cell seeding numbers. (f) Viability was determined by confocal microscopy (Leica SPS5) cell counting in a ROI 10 × . Pre-encapsulation staining of all cells in blue with lypophilic dye (Vybrant DiD, ThermoFisher) and metabolically active cells in green (Calcein AM, ThermoFisher) was done using previously employed methodology [31]. Statistical analysis was carried out using two-way ANOVA (*p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001). Scale bars: (a,d) 200 μm, (b,e) 100 μm. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)