Abstract

Introduction

In 2016, 2.6 million children died during their first month of life. We assessed the effectiveness of an integrated neonatal care kit (iNCK) on neonatal survival and other health outcomes in rural Pakistan.

Methods

We conducted a community-based, cluster randomised, pragmatic, open-label, controlled intervention trial in Rahim Yar Khan, Punjab, Pakistan. Clusters, 150 villages and their lady health workers (LHWs), were randomly assigned to deliver the iNCK (intervention) or standard of care (control). In intervention clusters, LHWs delivered the iNCK and education on its use to pregnant women. The iNCK contained a clean birth kit, chlorhexidine, sunflower oil, a continuous temperature monitor (ThermoSpot), a heat reflective blanket and reusable heat pack. LHWs were also given a hand-held scale. The iNCK was implemented primarily by caregivers. The primary outcome was all-cause neonatal mortality. Outcomes are reported at the individual level, adjusted for cluster allocation. Enrolment took place between April 2014 and July 2015 and participant follow-up concluded in August 2015.

Results

5451 pregnant women (2663 and 2788 in intervention and control arms, respectively) and their 5286 liveborn newborns (2585 and 2701 in intervention and control arms, respectively) were enrolled. 147 newborn deaths were reported, 65 in the intervention arm (25.4 per 1000 live births) compared with 82 in the control arm (30.6 per 1000 live births). Neonatal mortality was not significantly different between treatment groups (risk ratio 0.83, 95% CI 0.58 – 1.18; p = 0.30).

Conclusion

Providing co-packaged interventions directly to women did not significantly reduce neonatal mortality. Further research is needed to improve compliance with intended iNCK use.

Keywords: neonatal mortality, Pakistan, lady health worker, integrated intervention

Key questions.

What is already known?

There is a paucity of evidence on the effectiveness of integrated neonatal intervention packages that can be delivered by community health workers and implemented by women and families on improving neonatal health outcomes.

What are the new findings?

In this community-based, cluster randomised, pragmatic (effectiveness), open-label, controlled intervention trial, neonatal mortality rates were not significantly different between the intervention (25.4 per 1000 live births) and control group (30.6 per 1000 live births).

Caregiver implementation of the integrated neonatal care kit (iNCK) was effective at reducing the risk of omphalitis, which may predict or precede serious infection, and enabled caregivers to identify and take action to address fever, cold stress and hypothermia, symptoms that may indicate severe illness.

What do the new findings imply?

While the integration of evidence-based interventions for implementation by women and families is a promising idea that has several advantages, early uptake of some iNCK components was a challenge and the bundle of interventions did not translate into a statistically significant reduction in neonatal mortality.

Further research into the practical implications of the iNCK, including strategies to improve caregivers’ compliance with the intended use of the iNCK components, is necessary.

Introduction

In 2016, an estimated 2.6 million neonatal deaths occurred worldwide, accounting for 46% of all the deaths among children under 5 years of age.1 The third Sustainable Development Goal (SDG3) sets a target that all countries should aim to reduce neonatal mortality rates (NMRs) to no more than 12 deaths per 1000 live births by 2030.2 To meet this target, the accelerated scale-up of community-based interventions that are effective at reducing neonatal deaths is imperative.3–6

With 46 neonatal deaths per 1000 live births, Pakistan has the highest NMR in South Asia and the world.1 In 2015, the leading causes of neonatal death in Pakistan were prematurity (39%), birth asphyxia and trauma (21%) and sepsis (17%).7 If the average annual rate of reduction in NMR remains constant, Pakistan will not achieve the SDG3 target before 2081. Evidence-based interventions to improve neonatal survival exist4 8; however, their coverage is low, especially in rural communities, where many births and neonatal deaths occur at home.6 While some newborn interventions have been bundled into packages,9 very few packages have been delivered by community health workers (CHWs) and even fewer have been rigorously evaluated. One notable exception was the training and evaluation of traditional birth attendants in rural Zambia in the management of common perinatal conditions that led to significant reductions in newborn morality, especially those in the first 24 hours of life.10 Given that multiple barriers prevent CHWs from accessing a newborn soon after birth,11 efforts are needed to engage pregnant women and families as implementers of newborn interventions.5 The delivery of newborn intervention packages by CHWs for implementation by women and families has potential to sustainably reduce neonatal mortality.4

We conducted a community-based, cluster randomised, controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of delivering an integrated neonatal care kit (iNCK), and educating pregnant women and their families on its use, through an existing cadre of lady health workers (LHWs) on neonatal mortality. In Pakistan, LHWs are an important link between the health system and the community; each LHW provides primary healthcare to about 200 households in rural areas and urban slums.12 LHWs delivered the iNCK and education on its usage to participants. The iNCK contains a clean birth kit (CBK), 4% chlorhexidine solution, sunflower oil emollient, a temperature indicator sticker (ThermoSpot), a heat reflective polyester blanket, and a reusable heat pack. LHWs who delivered the iNCK were also provided a hand-held electronic scale. Each iNCK component was selected on the basis of evidence that it reduces the incidence of neonatal morbidities,13–18 or has potential to provide early identification of danger signs,19–21 or to enable caregivers to manage danger signs until healthcare is reached.22

Methods

Study design and oversight

We conducted a community-based, stratified cluster randomised, pragmatic (effectiveness), open-label, controlled, parallel two-arm intervention trial in Rahim Yar Khan (RYK) District, Pakistan from April 2014 until August 2015. Clusters were defined as villages and their associated LHWs. The protocol included two phases of work, separated by 11 months, that differed in the timing and frequency of data collection visits. Results of the first phase, during which frequent visits to households to collect compliance and outcome data were conducted, are reported here. The study protocol for the trial’s first phase was previously published22 and was approved by the Research Ethics Board at The Hospital for Sick Children (REB No. 100042963) and the National Bioethics Committee, Pakistan (No.4-87/13/NBC-133/RDC/2629). An independent data and safety monitoring board reviewed biweekly progress reports and a blinded interim analysis covering a period between April 2014 and February 2015. The trial is registered with Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02130856). Detailed study methods and protocol amendments (online supplementary table S1) are included in the online supplementary appendix.

bmjgh-2019-001393supp001.pdf (647.5KB, pdf)

Participants and procedures

All women in the third trimester of pregnancy within participating randomised clusters were considered eligible if they intended to stay in the study catchment area for at least 1 month after delivery. Participating LHWs identified pregnant women and notified the study team. A data collector visited pregnant women, explained the study and collected informed consent. The LHW delivered the iNCK and/or the standard of care12 (online supplementary panel 1). LHWs taught pregnant women how to use each iNCK component and were instructed to reiterate iNCK education at postdelivery visits. However, postnatal visits by LHWs were not incentivised or monitored by the study. LHWs were not financially compensated in this study. To encourage prompt birth notifications, a small monetary incentive was offered to the first person that reported the delivery to the study team. All liveborn newborns were prospectively followed.

bmjgh-2019-001393supp002.pdf (53.1KB, pdf)

Data collectors visited participants’ homes in both the intervention and control clusters as soon as possible after delivery, and on days 3, 7, 14 and 28. At the first visit, events surrounding delivery and the postnatal status of the newborn were documented. At subsequent visits, outcomes that arose since the previous visit were recorded. All questionnaires were administered as structured interviews. Newborns were weighed on the day of enrolment, and on days 7 and 28. Data collectors were trained to identify newborn danger signs (online supplementary appendix) and to refer cases to facilities. To minimise operational complexities while prioritising the collection of data as close to delivery as possible, births notified after day 3 were only visited on, or after, day 28; data on pregnancy outcome, iNCK use and newborn vital status were collected at these visits. In the event of neonatal death or stillbirth, a verbal autopsy was attempted.23

Intervention

The iNCK contains a CBK (gloves, soap, clean plastic sheet, sterile blade and cord clamps), 4% chlorhexidine solution, sunflower oil emollient, a continuous temperature indicator (ThermoSpot), a polyester blanket and an instant heat pack (online supplementary panel 1). At the time of iNCK delivery, LHWs individually taught expectant mothers how to use each iNCK component. If present, other caregivers (ie, mother-in-law, father, etc) were also engaged in the teaching session. Expectant mothers were instructed to take the entire iNCK to the facility at the time of delivery. In cases of home delivery, mothers were taught to provide the CBK to the birth attendant. Pregnant women were taught to apply chlorhexidine to the umbilical stump once daily from day 1 to day 10, and to apply one ThermoSpot sticker to the skin over the carotid artery on day 1 and leave it in place until day 14. Women were taught the meaning of each sticker colour and the actions to be taken if ThermoSpot indicated fever, cold stress or hypothermia. Sunflower oil was to be massaged over the newborn’s body once daily starting from day 3 until day 28. Each iNCK cost approximately US$10 to procure and assemble; however, at scale, the components of the iNCK can be sourced and assembled for less than US$5. LHWs in intervention clusters were provided a hand-held scale and were instructed to weigh newborns at their first postdelivery visit and to refer low birthweight (LBW) babies (<2500 g) to a health facility.

Outcomes

The primary study outcome was all-cause neonatal mortality. Neonatal deaths were documented by interview with caregivers at any study visit. Secondary outcomes include cumulative incidence of omphalitis, omphalitis severity (ascribed on the basis of observed inflammation) and severe infection24 (defined as the presence of any of the following symptoms: convulsions; tachypnea (60 breaths/min or more); fever; severe chest indrawing; movement only when stimulated or no movement; or feeding poorly or not feeding).24 With the exception of participant-reported feeding behaviours, symptoms were directly observed or measured by a data collector. Other secondary outcomes include the number of cases of hypothermia and fever identified by caregivers (using ThermoSpot), the proportion of newborns weighed within 3 days of birth by a LHW, and the proportion of LBW births identified by LHWs. Participants reported whether their newborns were weighed by a LHW and if so, the recorded weight. All outcome measures were recorded and analysed at the individual level accounting for cluster allocation. Additional secondary outcomes, which will be reported elsewhere, include neurodevelopment at 12 months, health facility use and the willingness to pay for the iNCK.

Sample size

The sample size of 75 clusters per arm was calculated based on an estimated crude birthrate of 25 per 1000 population, baseline NMR of 42 per 1000 live births and 35 live births per cluster during the study. These estimates were derived from survey data that were collected within RYK approximately 1.5 years before this trial launched (unpublished). We hypothesised a 40% reduction in all-cause neonatal mortality in the iNCK group compared with the control group. The magnitude of the anticipated effect size was in-part based on results from a clinical trial of chlorhexidine in Pakistan,16 in which the first application of chlorhexidine occurred by a traditional birth attendant and resulted in a 40% decrease in neonatal mortality. In addition to the estimated effect of chlorhexidine, we hypothesised that there would be a further additive mortality effect from the other iNCK components. With 90% enrolment of eligible mothers and up to a 10% loss-to-follow-up, and using a conservative intra-cluster correlation of 0.01 for NMR, 150 clusters (5250 newborns) were needed to detect a 40% reduction in mortality with at least 80% power.25

Stratification, randomisation and masking

To minimise contamination, randomisation occurred at the cluster level; however, data were recorded and analysed at the individual level, accounting for clustering. A scientist not directly involved in the study performed the cluster-stratified randomisation. Before randomisation, 157 villages were stratified into two groups: villages with 1 LHW or more than 1 LHW. Villages were not stratified based on location. To balance cluster size, one large village with five LHWs was excluded. In all, 150 clusters were randomly selected and allocated into either the iNCK (n=75) or standard of care (n=75) groups using a 1:1 allocation ratio and computer-generated numbers (Stata V.13). Study participants, LHWs and study team members were aware of group assignments. However, to reduce measurement bias, outcome data were collected by data collectors that were not involved in intervention delivery.

Statistical methods

Primary analyses of the effect of the intervention on outcomes were conducted as complete-case (ie, participants for whom vital status was known at the end of the neonatal period), intention-to-treat (ITT), irrespective of iNCK compliance and without imputation for missing data. Risk ratios (RR) were calculated using log-binomial regression on individual-level data and a robust variance estimator was used to account for cluster randomisation. Tests of significance were two-sided and did not adjust for baseline covariates. Post-hoc, complete-case, ITT analyses of the effect of the intervention on fever-alone and newborn mortality stratified by place of delivery, and age of death were conducted while accounting for clustering as described above. Post-hoc, complete-case, per protocol analyses of the effect of the intervention on neonatal mortality were also conducted (online supplementary appendix). Several additional post-hoc stratified analyses were performed (online supplementary appendix). Stata V.13 was used for all analyses.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the conceptualisation, design or conduct of this trial. The results of the trial will not be disseminated directly to participants.

Results

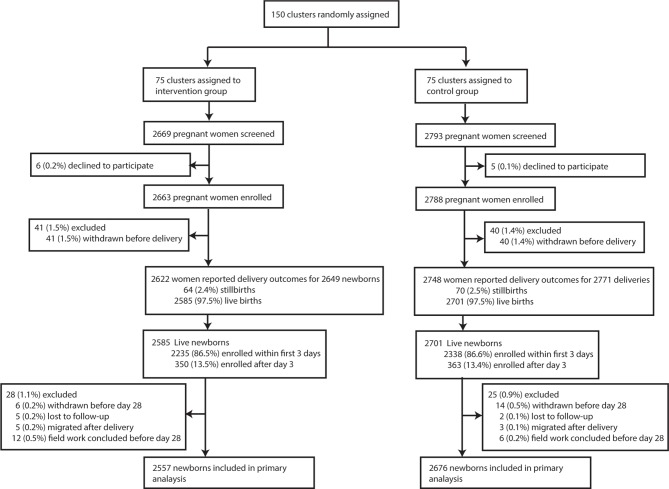

Between April 2014 and July 2015, 5451 pregnant women were enrolled in the study (2663 in the intervention group and 2788 in the control group) (table 1, figure 1). iNCKs were received between 1 and 22 weeks before delivery (median of 5 weeks) (online supplementary table S3). Delivery and newborn outcomes were collected between April 2014 and August 2015. A delivery outcome was collected for 5370 (98.5%) women (figure 1). There was no difference in place of delivery by treatment group with a total of 2107 (39.2%) women delivering at home (table 1). 5286 live-born deliveries were captured (2585 in the intervention and 2701 in the control arm). 134 (2.5%) stillbirths were reported and the stillbirth rate did not differ between groups (table 1). A total of 4573 visits (86.5%) occurred within 3 days of delivery (online supplementary table S4). Newborns enrolled after the first 3 days of life were equally distributed between arms (online supplementary table S4). Neonatal outcomes were available for 5233 (99.0%) newborns, 2557 (98.9%) in the intervention arm and 2676 (99.1%) in the control arm. About 80% of women in the intervention arm received some post-natal information by an LHW on how to use the iNCK (online supplementary table S3). However, only 28.6% (n=506) of women received their first post-natal LHW visit on day 1 of life (online supplementary table S3).

Table 1.

Maternal, delivery and newborn characteristics by treatment group

| Characteristics | Intervention | Control |

| Clusters randomised, n | 75 | 75 |

| Clusters contributed to enrolment*, n | 74 | 74 |

| Pregnant women enrolled per cluster, median (IQR) | 34 (24, 47) | 32 (21, 48) |

| Pregnant women enrolled by LHWs, n | 2663 | 2788 |

| Maternal age† (year), mean (SD) | 28.7 (4.3) | 28.7 (4.1) |

| Any ANC received†, n (%) | 2051 (92.7) | 2148 (92.7) |

| ANC4 coverage, n (%) | 738 (33.3) | 735 (31.7) |

| Tetanus toxoid coverage during pregnancy‡, n (%) | ||

| None | 292 (13.2) | 361 (15.6) |

| One | 310 (14.0) | 326 (14.1) |

| ≥Two | 1611 (72.8) | 1629 (70.3) |

| Gravidity†, median (min, max) | 3 (1, 18) | 3 (1, 18) |

| Place of delivery§, n (%) | ||

| Home | 1043 (39.8) | 1064 (38.7) |

| Facility | 1579 (60.2) | 1684 (61.3) |

| Type of delivery†, n (%) | ||

| Vaginal delivery | 1614 (72.9) | 1697 (73.2) |

| Caesarean section | 599 (27.1) | 621 (26.8) |

| Delivery attendant, n (%) | ||

| Doctor | 1082 (48.9) | 1195 (51.6) |

| Traditional birth attendant | 782 (35.3) | 785 (33.9) |

| Other | 349 (15.8) | 338 (14.6) |

| Delivery outcomes§, n (%) | ||

| Live singletons | 2533 (96.6) | 2660 (96.8) |

| Live multiples¶ | 25 (1.0) | 19 (0.7) |

| Stillbirth | 62 (2.4) | 68 (2.5) |

| One stillbirth and one live birth | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) |

| Twin stillbirths | – | 1 (0.0) |

| Total live born infants, n | 2585 | 2701 |

| Newborn sex**, n (%) | ||

| Male | 1189 (53.0) | 1238 (52.8) |

| Female | 1053 (47.0) | 1107 (47.2) |

| Gestational age at birth† (weeks) | ||

| Median, (IQR) | 39 (37, 40) | 39 (37, 40) |

| Preterm (<37 weeks), n (%) | 418 (18.7) | 447 (19.1) |

| Infant anthropometry | ||

| Birth weight†† (g), mean (SD) | 2752.2 (438.3) | 2731.4 (439.7) |

| Head circumference at birth‡‡(cm), mean (SD) | 32.4 (1.3) | 32.5 (1.3) |

| Age-/sex-standardised growth parameter | ||

| WAZ at birth,§§ mean (SD) | −1.08 (1.06) | −1.05 (1.02) |

| HCAZ at birth,¶¶ mean (SD) | −1.33 (1.04) | −1.29 (1.00) |

| Term low birth weight,*** n (%) | 362 (19.9) | 434 (23.0) |

| Small for gestational age, §§n (%) | 936 (42.6) | 938 (41.0) |

*Two clusters, one from each treatment group, did not contribute to enrolment. Each ‘missing’ cluster contained only 1 LHW and these LHWs remained inactive in their government position throughout the study period.

†n=2213 and n=2318 in intervention and control group, respectively. Gestational age at birth was calculated using self-reported first day of last menstrual period (LMP).

‡n=2213 and n=2316 in intervention and control group, respectively.

§Delivery outcomes were available for 2622 and 2748 women in intervention and control group, respectively.

¶In the intervention group, 25 twin pairs were delivered. In the control group, 17 twin pairs and 2 sets of triplets were delivered.

**n=2242 and n=2345 in intervention and control group, respectively.

††n=2186 and n=2278 in intervention and control group, respectively.

‡‡n=2006 and n=2081 in intervention and control group, respectively.

§§n=2196 and n=2288 in intervention and control group, respectively. WAZ at birth were calculated using the Intergrowth package.32

¶¶n=2017 and n=2094 in intervention and control group, respectively. HCAZ at birth were calculated using the Intergrowth package.32

***n=1817 and n=1891 in intervention and control group, respectively.

ANC, antenatal care; HCAZ, Head circumference for age z-scores; LHWs, lady health workers; WAZ, Weight for age z-scores.

Figure 1.

Trial profile (submitted as a separate file).

Most caregivers (n=2049, 91.7%) in the intervention arm reported that a CBK was used at the time of delivery compared with 1177 (50.3%) in the control arm (table 2). Almost every participant in the intervention group reported use of chlorhexidine (n=2209, 98.9%), sunflower oil (n=2209, 98.9%) and ThermoSpot (n=2204, 98.7%). However, compliance to instructions on timing of use varied. Only 704 (31.9%) participants who used chlorhexidine and 624 (28.3%) who used ThermoSpot started use, as intended, on day 1. Most participants (n=2079, 94.1%) in the intervention arm first applied sunflower oil on day 3. ThermoSpot enabled caregivers to identify 182 cases of fever, 15 cases of cold stress and 11 cases each of moderate and severe hypothermia (table 2). In the control arm, 1388 (60.7%) participants reported that Dettol, a locally available antiseptic, was applied to their baby’s umbilical stump (table 2) and mustard oil was commonly used for newborn massage (n=2291, 99.0%) (table 2).

Table 2.

Compliance to iNCK components in the intervention group and self-reported clean delivery, cord care and emollient practices in the standard of care group stratified by place of delivery

| Intervention | Control | ||||||

| Intervention | Utilisation | Total n=2233 | Facility delivery n=1351 | Home delivery n=882 | Total n=2338 | Facility delivery n=1440 | Home delivery n=898 |

| Clean birth kit | Used at time of delivery | 2049 (91.7) | 1213 (89.8) | 836 (94.6) | 1177 (50.3) | 1019 (70.8) | 158 (17.6) |

| Early initiation of breast feeding | Baby latched within 1 hour of delivery | 387 (17.3) | 176 (13.0) | 211 (23.9) | 372 (15.9) | 166 (11.5) | 206 (22.9) |

| Cord care | |||||||

| Any application of chlorhexidine | Used during neonatal period | 2209 (98.9) | 1330 (98.4) | 879 (99.7) | --- | --- | --- |

| First application on day 1* | 704 (31.9) | 350 (26.3) | 354 (40.3) | --- | --- | --- | |

| First application on day 2* | 725 (32.8) | 416 (31.3) | 309 (35.2) | --- | --- | --- | |

| First application on day 3* | 723 (32.7) | 519 (39.0) | 204 (23.2) | --- | --- | --- | |

| First application later than day 3* | 57 (2.6) | 45 (3.4) | 12 (1.4) | --- | --- | --- | |

| Exclusive application of chlorhexidine | Used during neonatal period† | 1621 (90.5) | 989 (90.8) | 632 (90.0) | --- | --- | --- |

| First application on day 1‡ | 484 (29.9) | 241 (24.4) | 243 (38.4) | --- | --- | --- | |

| First application on day 2‡ | 548 (33.8) | 315 (31.9) | 233 (36.9) | --- | --- | --- | |

| First application on day 3‡ | 561 (34.6) | 409 (41.4) | 152 (24.1) | --- | --- | --- | |

| First application later than day 3‡ | 28 (1.7) | 24 (2.4) | 4 (0.6) | --- | --- | --- | |

| Application of chlorhexidine and other substance | Used during neonatal period† | 170 (9.5) | 100 (9.2) | 70 (10.0) | --- | --- | --- |

| Surma§ | 82 (48.2) | 35 (35.0) | 47 (67.1) | --- | --- | --- | |

| Dettol§ | 65 (38.2) | 53 (53.0) | 12 (17.1) | --- | --- | --- | |

| Oil§ | 33 (19.4) | 19 (19.0) | 14 (20.0) | --- | --- | --- | |

| Turmeric§ | 10 (5.9) | 7 (7.0) | 3 (4.3) | --- | --- | --- | |

| Other§ | 9 (5.3) | 5 (5.0) | 4 (5.7) | --- | --- | --- | |

| Other substance only | Used during neonatal period¶ | 6 (37.5) | 5 (33.3) | 1 (100.0) | 2285 (97.7) | 1400 (97.2) | 885 (98.6) |

| Dettol** | 4 (66.7) | 4 (80.0) | --- | 1388 (60.7) | 1018 (72.7) | 370 (41.8) | |

| Surma** | 2 (33.3) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1174 (51.4) | 584 (41.7) | 590 (66.7) | |

| Ghee** | --- | --- | --- | 228 (10.0) | 113 (12.8) | 115 (8.2) | |

| Oil** | 2 (33.3) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (100.0) | 851 (37.2) | 475 (33.9) | 376 (42.5) | |

| Turmeric** | --- | --- | --- | 80 (3.5) | 39 (2.8) | 41 (4.6) | |

| Other** | --- | --- | --- | 93 (4.0) | 55 (3.8) | 38 (4.2) | |

| Emollient usage | |||||||

| Sunflower oil emollient | Used during neonatal period | 2209 (98.9) | 1331 (98.5) | 878 (99.5) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | --- |

| First application before day 3†† | 58 (2.6) | 28 (2.1) | 30 (3.4) | --- | --- | --- | |

| First application on day 3†† | 2079 (94.1) | 1243 (93.4) | 836 (95.2) | --- | --- | --- | |

| First application later than day 3†† | 72 (3.3) | 60 (4.5) | 12 (1.4) | --- | --- | --- | |

| Other emollient used | Used during neonatal period‡‡ | 42 (30.9) | 30 (26.3) | 12 (54.5) | 2315 (99.0) | 1419 (98.5) | 896 (99.8) |

| Mustard§§ | 36 (85.7) | 25 (83.3) | 11 (91.7) | 2291 (99.0) | 1402 (98.8) | 889 (99.2) | |

| Ghee§§ | 3 (7.1) | 2 (6.7) | 1 (8.3) | 197 (8.5) | 119 (8.4) | 78 (8.7) | |

| Lotion§§ | 5 (11.9) | 5 (16.7) | --- | 157 (6.8) | 121 (8.5) | 36 (4.0) | |

| Other§§ | --- | --- | --- | 67 (2.9) | 49 (3.4) | 18 (2.0) | |

| Intervention | Control | ||||||

| Intervention | Utilisation | Total n=2233 | Facility delivery n=1351 | Home delivery n=882 | Total | Facility delivery | Home delivery |

| Thermal care | |||||||

| TS | Used during neonatal period | 2204 (98.7) | 1329 (98.4) | 875 (99.2) | --- | --- | --- |

| First application on day 1¶¶ | 624 (28.3) | 298 (22.4) | 326 (37.3) | --- | --- | --- | |

| First application on day 2¶¶ | 686 (31.1) | 381 (28.7) | 305 (34.9) | --- | --- | --- | |

| First application on day 3¶¶ | 828 (37.6) | 591 (44.5) | 237 (27.1) | --- | --- | --- | |

| First application later than day 3¶¶ | 66 (3.0) | 59 (4.4) | 7 (0.8) | --- | --- | --- | |

| ThermoAction (ie, heat pack, reflective blanket, seeking healthcare) |

Number of time TS turned blue (fever)*** | 182 | 114 | 68 | --- | --- | --- |

| Healthcare Sought††† | 152 (83.5) | 94 (82.5) | 58 (85.3) | --- | --- | --- | |

| Number of times TS turned pale green (cold stress)*** | 15 | 8 | 7 | --- | --- | --- | |

| Skin-to-skin care initiated‡‡‡ | 15 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | --- | --- | --- | |

| Number of times TS turned red (moderate hypothermia)*** | 11 | 6 | 5 | --- | --- | --- | |

| All three: blanket, heat pack and healthcare§§§ | 5 (45.5) | 3 (27.3) | 2 (18.2) | --- | --- | --- | |

| Any two of: blanket, heat pack or healthcare§§§ | 4 (36.4) | 4 (36.4) | 4 (36.4) | --- | --- | --- | |

| Any one of: blanket, heat pack or healthcare§§§ | 1 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | --- | --- | --- | |

| None: blanket, heater or healthcare§§§ | 1 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | --- | --- | --- | |

| Number of times TS turned black (severe hypothermia) | 11 | 8 | 3 | --- | --- | --- | |

| All three: blanket, heat pack and healthcare¶¶¶ | 6 (54.5) | 4 (36.4) | 2 (18.2) | --- | --- | --- | |

| Any two of: blanket, heat pack or health care¶¶¶ | 1 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) | --- | --- | --- | |

| Any one of: blanket, heat pack or healthcare¶¶¶ | 1 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) | --- | --- | --- | |

| None: blanket, heat pack or healthcare¶¶¶ | 3 (27.3) | 3 (27.3) | 0 (0.0) | --- | --- | --- | |

*n=2209 in the total group, n=1330 in the facility delivery group, n=879 in the home delivery group. Denominators reflect the number of participants who used chlorhexidine.

†n=1791 in the total group, n=1089 in the facility delivery group, n=702 in the home delivery group. Denominators reflect the number of participants who used chlorhexidine and responded to queries regarding the use of other substance to the umbilical cord.

‡n=1621 in the total group, n=989 in the facility delivery group, n=632 in the home delivery group. Denominators reflect the number of participants who reported to have used chlorhexidine exclusively.

§n=170 in the total group, n=100 in the facility delivery group, n=70 in the home delivery group. Denominators reflect the number of participants who reported to have used chlorhexidine and applied other substance to the umbilical cord. When asked about the application of ‘other’ substances to the umbilical cord, participants could respond with more than one answer.

¶n=16 in the total group, n=15 in the facility delivery group, n=1 in the home delivery group. n=2338 in the control total group, n=1440 in the control facility delivery group, n=898 in the control home delivery group. Denominators reflect the number of participants who reported to have only applied a substance other than chlorhexidine to the umbilical cord.

**n=6 in the intervention total group, n=5 in the intervention facility delivery group, n=1 in the intervention home delivery group. n=2285 in the control total group, n=1400 in the control facility delivery group, n=885 in the control home delivery group. Denominators reflect the number of participants who reported to have only applied a substance other than chlorhexidine to the umbilical cord. When asked about the application of ‘other’ substances to the umbilical cord, participants could respond with more than one answer.

††n=2209 in the total group, n=1331 in the facility delivery group, n=878 in the home delivery group. Denominators reflect the number of participants who used sunflower oil emollient.

‡‡n=136 in the intervention total group, n=114 in the intervention facility delivery group, n=22 in the intervention home delivery group. n=2338 in the control total group, n=1440 in the control facility delivery group, n=898 in the control home delivery group. Denominators reflect the number of participants who used and responded to queries regarding the use of emollients other than sunflower oil.

§§n=42 in the intervention total group, n=30 in the intervention facility delivery group, n=12 in the intervention home delivery group. n=2315 in the control total group, n=1419 in the control facility delivery group, n=896 in the control home delivery group. Denominators reflect the number of participants who reported to have used an oil other than sunflower oil. When asked about the application of ‘other’ oil usage, participants could respond with more than one answer. Data were not available to distinguish between any oil application and exclusive oil application in the intervention group and only 136 participants in the kit group who used sunflower oil to massage their newborns were asked if they also used other oils for massage.

¶¶n=2204 in the intervention total group, n=1329 in the intervention facility delivery group, n=875 in the intervention home delivery group. Denominators reflect the number of participants who reported to have used TS.

***Fever was defined via TS as a temperature of ≥39.0°C; Cold stress was defined via TS as a temperature between 36.0°C and 36.4°C; moderate and severe hypothermia were defined via TS as temperatures between ≥35.5 and<36.0°C and <35.5°C, respectively.

†††n=182 in total group, n=114 in facility delivery group, n=68 in home delivery group. Denominators reflect the number of participants who reported that TS turned blue (indicated fever).

‡‡‡n=15 in the intervention total group, n=8 in the intervention facility delivery group, n=7 in the intervention home delivery group. Denominators reflect the number of participants who reported that TS turned light green (cold stress).

§§§n=11 in the intervention total group, n=6 in the intervention facility delivery group, n=5 in the intervention home delivery group. Denominators reflect the number of participants who reported that TS turned red (moderate hypothermia).

¶¶¶n=11 in the intervention total group, n=8 in the intervention facility delivery group, n=3 in the intervention home delivery group. Denominators reflect the number of participants who reported that TS turned block (severe hypothermia).

TS, ThermoSpot; iNCK, integrated neonatal care kit.

A total of 147 newborn deaths were reported, 65 in the intervention arm (25.4 per 1000 live births) compared with 82 in the control arm (30.6 per 1000 live births). The overall mortality risk was not significantly different between the two groups (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.18; p=0.30) (table 3). NMRs also did not differ between treatment arms when stratified by age of death and place of delivery (table 3). In a post-hoc per protocol analysis, a general trend emerged whereby increasing compliance improved the efficacy of the kit (online supplementary tables S8, S9).

Table 3.

All-cause newborn mortality by treatment group

| Intervention | Control | Risk ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| Intention-to-treat, complete case population | ||||

| Overall newborn mortality | ||||

| Live births, n | 2557 | 2676 | ||

| All newborn deaths, n | 65 | 82 | ||

| Neonatal mortality rate (per 1000 live births) | 25.4 | 30.6 | 0.83 (0.58 to 1.18) | 0.30* |

| Age of newborn death (days), median (IQR) | 3 (2, 8) | 3 (1, 5) | ||

| Newborn mortality by age of newborn death | ||||

| Early newborn mortality | ||||

| Live births, n | 2557 | 2676 | ||

| Early newborn deaths (fewer than seven completed days), n | 47 | 66 | ||

| Early neonatal mortality rate (per 1000 live births) | 18.4 | 24.7 | 0.75 (0.50 to 1.10) | 0.14† |

| Age of early newborn death (days), median (IQR) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 4) | ||

| Late newborn mortality | ||||

| Live births who survived the first week, n | 2510 | 2610 | ||

| Late newborn deaths (after 7 but before 28 completed days), n | 18 | 16 | ||

| Late neonatal mortality rate (per 1000 live births) | 7.2 | 6.1 | 1.17 (0.54 to 2.56) | 0.69‡ |

| Age of late newborn death (days), median (IQR) | 16 (9, 20) | 16 (14, 21) | ||

| Newborn mortality by place of delivery | ||||

| Home delivery | ||||

| Live births, n | 1011 | 1033 | ||

| Newborn deaths, n | 26 | 29 | ||

| Neonatal mortality rate (per 1000 live births) | 25.7 | 28.1 | 0.92 (0.55 to 1.52) | 0.74§ |

| Age of newborn death (days), median (IQR) | 3 (2, 4) | 2 (1, 5) | ||

| Facility delivery | ||||

| Live births, n | 1546 | 1643 | ||

| Newborn deaths, n | 39 | 53 | ||

| Neonatal mortality rate (per 1000 live births) | 25.2 | 32.3 | 0.78 (0.50 to 1.22) | 0.28¶ |

| Age of newborn death (days), median (IQR) | 3 (1, 9) | 3 (1, 5) | ||

Intracluster correlation coefficients have been calculated as *0.05, †0.04, ‡0.22, §0.00, ¶0.65.

The risk of omphalitis, irrespective of severity, was 32% lower in the intervention arm compared with the control arm (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.98; p=0.04) (table 4). The risk of moderate omphalitis was reduced by 62% (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.94; p=0.04). There was no significant difference in the risk of mild (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.03; p=0.07) or severe omphalitis (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.05 to 5.74; p=0.60) between groups (table 4).

Table 4.

Omphalitis, severe infection and identification of low birthweight newborns by LHWs by treatment group

| Intervention | Control | Risk ratio (95% CI) |

P value | |

| Any omphalitis*, n (%) | 101 (4.5) | 155 (6.7) | 0.68 (0.48 to 0.98) | 0.04† |

| Mild omphalitis, n (%) | 91 (4.1) | 133 (5.7) | 0.72 (0.50 to 1.03) | 0.07 |

| Moderate omphalitis, n (%) | 9 (0.4) | 25 (1.1) | 0.38 (0.15 to 0.94) | 0.04 |

| Severe omphalitis, n (%) | 1 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 0.52 (0.05 to 5.74) | 0.60 |

| Any sign severe infection*, n (%) | 426 (19.1) | 380 (16.3) | 1.17 (0.80 to 1.72) | 0.41‡ |

| Convulsions, n (%) | 3 (0.1) | 4 (0.2) | 0.79 (0.14 to 4.37) | 0.78 |

| Fast breathing, n (%) | 23 (1.0) | 41 (1.8) | 0.59 (0.32 to 1.08) | 0.08 |

| Indrawing, n (%) | 18 (0.8) | 24 (1.0) | 0.79 (0.40 to 1.53) | 0.48 |

| Fever, n (%) | 83 (3.7) | 136 (5.8) | 0.64 (0.47 to 0.87) | 0.004 |

| Poor feeding, n (%) | 363 (16.3) | 292 (12.5) | 1.30 (0.80 to 2.13) | 0.29 |

| Sign of abnormal activity level, n (%) | 222 (10.0) | 182 (7.8) | 1.28 (0.75 to 2.17) | 0.37 |

| Newborns born at home and weighed within 3 days by a LHW§, n (%) | 147 (16.6) | 31 (3.5) | 4.81 (1.96 to 11.80) | 0.001¶ |

| Day 1 | 89 (60.5) | 10 (32.3) | ||

| Day 2 | 46 (31.3) | 19 (61.3) | ||

| Day 3 | 12 (8.2) | 2 (6.5) | ||

| All LBW babies identified among home deliveries in the study population**, n (%) | 228 (25.9) | 251 (28.1) | 0.92 (0.75 to 1.13) | 0.43†† |

| LBW babies identified by a LHW, n (%) | 24 (2.7) | 7 (0.8) | 3.48 (1.00 to 12.10) | 0.05 |

| LBW babies identified by a study worker, n (%) | 226 (25.7) | 250 (28.0) | 0.92 (0.75 to 1.12) | 0.40 |

*Live births for whom at least one data collection visit was available in the intervention (n=2225) and control (n=2329) arms where umbilical cord or severe infection could be observed were included.

†Intracluster correlation coefficients have been calculated as 0.13.

‡Intracluster correlation coefficients have been calculated as 0.30.

§Live births born at home and visited within the first 3 days of life who self-reported whether a LHW weighed their baby soon after delivery in the intervention (n=886) and control (n=898) arms were included.

¶Intracluster correlation coefficients have been calculated as 0.62.

**Live births born at home and visited within 3 days of life in the intervention (n=881) and control (n=893) arms were included.

††Intracluster correlation coefficients have been calculated as 0.07.

LBW, low birthweight; LHWs, lady health workers.

The risk of severe infection was not different between groups (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.72; p=0.41) (table 4); however, the risk of fever was lower in the iNCK group compared with the control group (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.87; p=0.004). The proportion of newborns born at home and weighed by a LHW was higher in the intervention arm compared with the control arm (RR 4.81, 95% CI 1.96 to 11.80; p<0.001). Among home births, a larger proportion of LBW babies were identified by LHWs in the intervention arm compared with the control group (RR 3.48, 95% CI 1.00 to 12.10; p=0.05) (table 4).

No adverse events were reported.

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to assess whether a package of six evidence-based neonatal interventions in conjunction with teaching, when delivered directly to pregnant women and families by LHWs, would reduce neonatal mortality. In fact, the provision of the iNCK to pregnant women and families did not significantly lower neonatal mortality compared with the standard of care in RYK, Pakistan.

The absence of a significant mortality effect may be attributable to several factors. First, while overall utilisation of the iNCK components was high, instructions regarding the timing of usage were not always followed. For example, while 99% of participants in the iNCK group used chlorhexidine, only about 30% of these participants first applied chlorhexidine on day 1, as was instructed. Application of chlorhexidine within the first 24 hours of life is important for improving newborn survival.15 17 Similarly, while 99% of participants used ThermoSpot, only 28% of these participants applied ThermoSpot on day 1. Since most newborn deaths happen within 24 hours of delivery, the ability to detect fever and hypothermia soon after delivery is imperative. Second, the effect of the iNCK may have been diluted by the use of similar interventions in control clusters. For example, approximately 50% of women in the control group reported use of a CBK at delivery. Similarly, about 60% of participants in the control group reported that Dettol was applied to their newborn’s umbilicus. Chloroxylenol, the antiseptic in Dettol, reduces bacterial burden but, based on animal studies, may not do so as effectively as chlorhexidine.26 Third, the relatively low proportion of home deliveries (39%) may have attenuated the effect of chlorhexidine on mortality. Evidence suggests that chlorhexidine has a larger effect on neonatal mortality in settings with higher proportions of home deliveries and higher NMRs27; however, it is also important to highlight that meta-analyses, which have included both home and facility births, have concluded that chlorhexidine reduces the risk of both omphalitis and death in both of these settings.14 Fourth, frequent home visits by study personnel may have acted like a co-intervention28 and thus, improved neonatal health in all study participants; the NMR in the control group (30.6 deaths per 1000 live births) was lower than the anticipated NMR (42 deaths per 1000 live births). Similarly, among participants that had zero home visits in the first week of life, the NMR was 29% lower in the iNCK arm compared with the control arm (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.18). By contrast, among participants that had one or more home visits in the first week of life, NMR was only 5% lower in the iNCK arm compared with the control arm (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.53) (online supplementary table S5). Finally, given that the average temperature in RYK ranged from 21°C (January 2015) to 43C (July 2014) over the study period, the utility of the heater and blanket may have been diminished.

While the iNCK did not significantly reduce neonatal mortality, several findings support further investigation of the iNCK. First, existing community health infrastructure was leveraged to distribute the iNCK, demonstrating the feasibility of this platform for future programmes. Second, CBKs were more frequently used during home deliveries when provided directly to pregnant women in intervention clusters compared with pregnant women in control clusters (94.6% vs 17.6%). Third, caregiver utilisation of the iNCK was effective at reducing the risk of omphalitis and fever, both of which may predict or precede serious infection. Caregiver implementation of interventions is likely more sustainable and less costly than having CHWs conduct routine home visits to implement interventions. Fourth, ThermoSpot enabled caregivers to identify and act on cases of fever, cold stress and hypothermia, symptoms that may indicate severe illness. Fifth, providing a scale to LHWs increased the proportion of LBW babies identified; however, participant uptake for LBW referrals is unknown. LBW is a risk factor for neonatal mortality and early detection is important for referral and subsequent management. Sixth, mustard oil, for which there are documented adverse effects on epidermal structure and barrier function,29 was used by approximately 99% of participants in the standard of care arm. Newborn massage with sunflower oil offers a safer alternative to mustard oil that has documented benefits.29 While we are unable to report whether caregivers completely replaced the application of mustard oil with sunflower oil emollient in the intervention group, the greater than 98% uptake of sunflower oil in the iNCK arm suggests that there is potential for adapting an established cultural practice with one that is safer and has greater benefits.29 30 Finally, a general trend emerged whereby increasing compliance improved the efficacy of the iNCK.

There were some limitations to this study. First, since compliance data were self-reported, they may be distorted by social desirability bias. Second, gaps in the information collected during the trial prevent us from making inferences on how LHW engagement, acceptance of LHW referrals for LBW identification, barriers to timely LHW postnatal visits, LHW teaching quality and other process indicators may have influenced compliance and neonatal outcomes. Third, since villages were not stratified based on location, contamination may have occurred between clusters. However, data collected on the utilisation of iNCK components in control clusters suggests that contamination did not occur. Fourth, while the diagnosis of omphalitis was conducted by trained data collectors, we did not validate our diagnosis algorithm against a gold standard within this study population, photos were not taken of the cord to allow for post-hoc adjudication of infection, and inflammation, which was shown to have low sensitivity (12%) for community-based assessment of omphalitis in Nepal,17 was included as a sign within our diagnosis algorithm. Without real-time in-person parallel gold standard assessment,31 the validity of omphalitis diagnoses should be interpreted with caution. Finally, the effect size that was used to estimate the sample size (40%) and the fact that it was not realised, meant that statistical significance was not achieved. That said, the approximately 20% reduction in NMR that was estimated, while not statistically significant, may represent a genuine effect that is clinically meaningful and should not be discounted.

The integration of evidence-based interventions for implementation by caregivers has long been considered a promising means to improve neonatal survival.11 We demonstrated that, while the idea of integrating interventions, delivering packages by LHWs and engaging caregivers as implementers, has several advantages, it did not translate into improved neonatal survival. Further research into the practical implications of the iNCK, including strategies to improve caregivers’ compliance, is necessary.

Registration

The trial is registered with Clinicaltrials.gov, number NCT02130856, under the title ‘Newborn Kit to Save Lives in Pakistan’.

Protocol

The trial protocol was previously published.22

Footnotes

Handling editor: Douglas James Noble

Contributors: SKM and ZAB conceptualised the study idea. SKM, LGP, AT, DGB, SS, SA, MH and ZAB played a role in the study’s design, planning and implementation. LGP and JS analysed the data. LGP wrote the first draft of the manuscript and led revisions. All authors read, contributed edits and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This project was funded by Grand Challenges Canada (S4 0230-01), UBS Optimus Foundation (6793_UBSOF) and March of Dimes Foundation (#5-FY14-48). Baby Hero (https://babyhe.ro) further supported the study. SKM received support from the Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist Program. The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation or writing of the report.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Research Ethics Board at The Hospital for Sick Children (REB No. 100042963) National Bioethics Committee, Pakistan (No.4-87/13/NBC-133/RDC/2629).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality E Levels and trends in child mortality: report 2015. New York, NY: UNICEF; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. UN General Assembly Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development, 21 October 2015, A/RES/70/1. Available: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf [Accessed 25 mar 2019].

- 3. Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, et al. . Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet 2012;379:2151–61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Bahl R, et al. . Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost? Lancet 2014;384:347–70. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60792-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yoshida S, Martines J, Lawn JE, et al. . Setting research priorities to improve global newborn health and prevent stillbirths by 2025. J Glob Health 2016;6:010508 10.7189/jogh.06.010508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bhutta ZA, Hafeez A, Rizvi A, et al. . Reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health in Pakistan: challenges and opportunities. Lancet 2013;381:2207–18. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61999-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. UNICEF Maternal and newborn health disparities: Pakistan.

- 8. Bhutta ZA, Darmstadt GL, Hasan BS, et al. . Community-based interventions for improving perinatal and neonatal health outcomes in developing countries: a review of the evidence. Pediatrics 2005;115(2 Suppl):519–617. 10.1542/peds.2004-1441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haws RA, Thomas AL, Bhutta ZA, et al. . Impact of packaged interventions on neonatal health: a review of the evidence. Health Policy Plan 2007;22:193–215. 10.1093/heapol/czm009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gill CJ, Phiri-Mazala G, Guerina NG, et al. . Effect of training traditional birth attendants on neonatal mortality (Lufwanyama neonatal survival project): randomised controlled study. BMJ 2011;342:d346 10.1136/bmj.d346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Soofi S, Cousens S, Turab A, et al. . Effect of provision of home-based curative health services by public sector health-care providers on neonatal survival: a community-based cluster-randomised trial in rural Pakistan. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e796–806. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30248-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hafeez A, Mohamud BK, Shiekh MR, et al. . Lady health workers programme in Pakistan: challenges, achievements and the way forward. J Pak Med Assoc 2011;61:210–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seward N, Osrin D, Li L, et al. . Association between clean delivery kit use, clean delivery practices, and neonatal survival: pooled analysis of data from three sites in South Asia. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001180 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Imdad A, Mullany LC, Baqui AH, et al. . The effect of umbilical cord cleansing with chlorhexidine on omphalitis and neonatal mortality in community settings in developing countries: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2013;13(Suppl 3). 10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mullany LC, Darmstadt GL, Khatry SK, et al. . Topical applications of chlorhexidine to the umbilical cord for prevention of omphalitis and neonatal mortality in southern Nepal: a community-based, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2006;367:910–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68381-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Soofi S, Cousens S, Imdad A, et al. . Topical application of chlorhexidine to neonatal umbilical cords for prevention of omphalitis and neonatal mortality in a rural district of Pakistan: a community-based, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2012;379:1029–36. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61877-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arifeen SE, Mullany LC, Shah R, et al. . The effect of cord cleansing with chlorhexidine on neonatal mortality in rural Bangladesh: a community-based, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2012;379:1022–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61848-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Salam RA, Das JK, Darmstadt GL, et al. . Emollient therapy for preterm newborn infants – evidence from the developing world. BMC Public Health 2013;13(Suppl 3). 10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mole TB, Kennedy N, Ndoya N, et al. . ThermoSpots to detect hypothermia in children with severe acute malnutrition. PLoS One 2012;7:e45823 10.1371/journal.pone.0045823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Green DA, Kumar A, Khanna R. Neonatal hypothermia detection by ThermoSpot in Indian urban slum dwellings. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2006;91:F96–F98. 10.1136/adc.2005.078410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kennedy N, Gondwe L, Morley DC. Temperature monitoring with ThermoSpots in Malawi. The Lancet 2000;355 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)72592-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Turab A, Pell LG, Bassani DG, et al. . The community-based delivery of an innovative neonatal kit to save newborn lives in rural Pakistan: design of a cluster randomized trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14 10.1186/1471-2393-14-315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Organization WH Verbal autopsy standards: the 2012 who verbal autopsy instrument. WHO library Cataloguing-in-Publication data 2012.

- 24. World Health Organization Guideline: managing possible serious bacterial infection in young infants when referral is not feasible 2015. [PubMed]

- 25. Donner A, Klar N. Design and analysis of cluster randomization trials in health research. Great Britain: Arnold, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stubbs WP, Bellah JR, Vermaas-Hekman D, et al. . Chlorhexidine gluconate versus chloroxylenol for preoperative skin preparation in dogs. Vet Surg 1996;25:487–94. 10.1111/j.1532-950X.1996.tb01448.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Osrin D, Colbourn T. No reason to change WHO guidelines on cleansing the umbilical cord. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e766–8. 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30258-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gogia S, Sachdev HS. Home visits by community health workers to prevent neonatal deaths in developing countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:658–66. 10.2471/BLT.09.069369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Darmstadt GL, Mao-Qiang M, Chi E, et al. . Impact of topical oils on the skin barrier: possible implications for neonatal health in developing countries. Acta Paediatr 2002;91:546–54. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2002.tb03275.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Darmstadt GL, Saha SK, Ahmed ASMNU, et al. . Effect of skin barrier therapy on neonatal mortality rates in preterm infants in Bangladesh: a randomized, controlled, clinical trial. Pediatrics 2008;121:522–9. 10.1542/peds.2007-0213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Herlihy JM, Gille S, Grogan C, et al. . Can community health workers identify omphalitis? a validation study from southern Province, Zambia. Trop Med Int Health 2018;23:806–13. 10.1111/tmi.13074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Villar J, Cheikh Ismail L, Victora CG, et al. . International standards for newborn weight, length, and head circumference by gestational age and sex: the newborn cross-sectional study of the INTERGROWTH-21st project. Lancet 2014;384:857–68. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60932-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2019-001393supp001.pdf (647.5KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2019-001393supp002.pdf (53.1KB, pdf)