Introduction

In its current form, the Medicare annual wellness visit (AWV) is not reaching most older Americans, particularly lower-income or minority adults and those served by safety-net providers (Ganguli, Souza, McWilliams, & Mehrotra, 2018). Yet these underserved seniors face disparities in healthy aging, likely due to individual, social, and behavioral determinants of health, such as low income, limited education, social isolation, food insecurity, poor housing quality, and difficulty affording medications. New AWV models should move beyond traditional assessments of cognition, balance, and vision to identify and address important root causes of poor health, such as individual, social, and behavioral determinants of health. Incorporating these key determinants of health into AWVs has the potential to promote healthy aging among underserved seniors. In this paper, we present local opportunities for AWV-related practice transformation, including screening tools, electronic health record templates, care team member roles, and workflows. At the national level, we suggest updates to Medicare’s current AWV policy guidelines with regard to visit elements and funding models.

Disparities in Healthy Aging

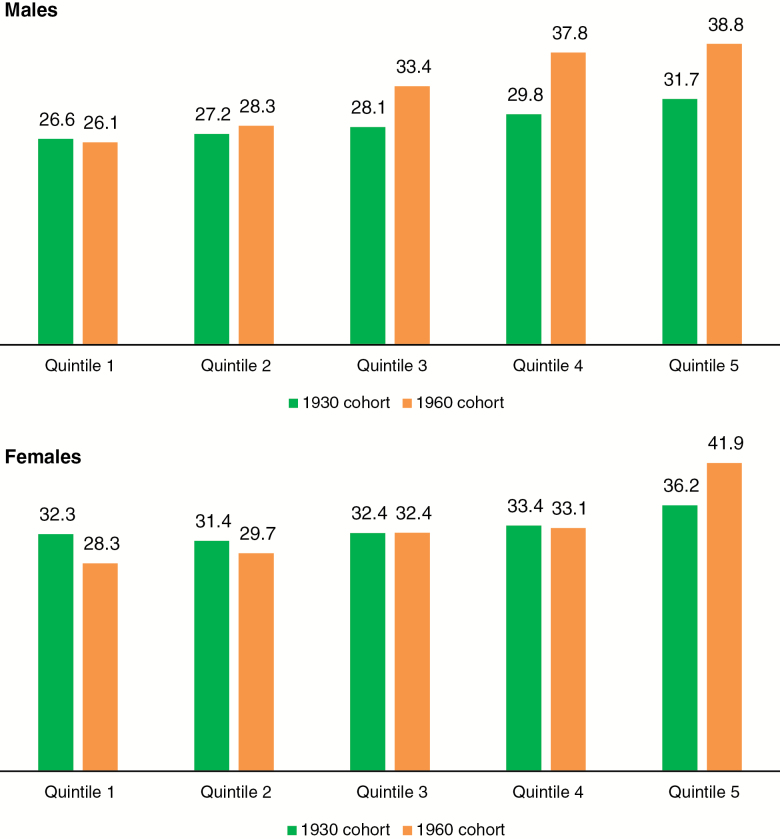

The gap in healthy aging between individuals of lower and higher socioeconomic status (SES) continues to grow in the United States. With regard to life expectancy, Chetty and colleagues (2016) found that between 2001 and 2014, the top 5% of income earners gained almost 3 years in life expectancy, while the bottom 5% made no real gains. There are similar disparities in life expectancy among those with less and more education. Olshansky and colleagues, building on earlier work by others, found that the difference in life expectancy between those with the greatest and least educational attainment ranged from 3 to 13 years (depending on race and gender), despite a steady rise in the average life expectancy for the population (Meara, Richards, & Cutler, 2008; Olshansky et al., 2012). According to a recent National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report, this disparity appears to have been cumulative; over the past several decades, the overall gap in life expectancy between the lowest and highest income quintiles has grown from 5.1 to 12.7 years among men and from 3.9 to 13.6 years among women (see Figure 1; The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2015).

Figure 1.

Estimated and projected life expectancy at age 50 for males and females born in 1930 and 1960, by income quintile. Data are from the Health and Retirement Study and the figure is from The National Academies of Sciences Engineering Medicine (2018).

Such disparities are likewise apparent in the general health status of older adults. While older adults who are White, well educated, or more affluent have become more likely to experience good health, older adults who are African-American, Hispanic, less educated, or less affluent have become less likely to report good health (Davis, Guo, Sol, Langa, & Nallamothu, 2017). Similarly, improvements in the control of key cardiovascular risk factors, such as smoking and hypertension, have been achieved among high-income U.S. adults in the past 15 years, but not among those living in poverty, leading to a widening of overall cardiovascular risk between rich and poor adults (Odutayo et al., 2017).

These differences may translate into functional disabilities and other impairments. Schoeni and colleagues found that between 1982 and 2002, the gap between adults aged 70 or older with lower and higher SES widened substantially in the ability to perform basic activities of daily living (Schoeni, Martin, Andreski, & Freedman, 2005). Low-SES baby boomers, in particular, appear to be experiencing a process of accelerated aging, characterized by greater numbers of chronic conditions and declines in general health, mental health, and functional status, compared with prior cohorts of Americans (Case & Deaton, 2015; Heiss, Venti, & Wise, 2014; Soldo, Mitchell, Tfaily, & McCabe, 2006).

Addressing these gaps will require a multi-pronged approach. As Schoeni writes, “Disability is a function of both underlying physical capacity and the environment in which a person lives and works … To close completely the gaps in late-life functioning may require a combination of medical, behavioral, and environmental interventions” (p. 2069) (Schoeni et al., 2005). Thus, healthy aging relies not only on the ability of older adults to maintain a minimum level of physical functioning, but also on (1) factors specific to the individual, such as income and education; (2) factors that are related to an individual’s social context, such as the ability to access healthy food and obtain stable housing; and (3) behavioral factors, such as smoking cessation and maintaining rich social connections with family and friends. Such “social determinants of health” often play a large role in determining the health trajectories of vulnerable populations at all ages (Wilensky & Satcher, 2009). In addition, cardiovascular risk factors, such as smoking and hypertension, are highly influenced by social determinants of health (e.g., ability to afford medications to quit smoking or control blood pressure).

Health-care system leaders and policymakers are increasingly recognizing the medical impact of these social determinants and the potential for health-care solutions to address the widening disparities in health and longevity for older adults with lower SES. While these recent efforts have been more common in Medicaid managed-care organizations and hospital systems, there is an opportunity for the Medicare program to further embrace this approach (Alley, Asomugha, Conway, & Sanghavi, 2016; Gottlieb, Ackerman, Wing, & Manchanda, 2017; Gottlieb, Garcia, Wing, & Manchanda, 2016; Johnson, 2018). The Medicare AWV may provide one pathway to addressing social determinants of health in health care and reducing gaps in healthy aging (Tipirneni & Langa, 2018).

Elements and Effectiveness of the Current Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) introduced the AWV in January 2011 in an effort to improve healthy aging among older adults. The AWV was meant to go beyond focusing on individual chronic diseases, to identifying and addressing broader health risks and promoting preventive health screenings in seniors. The AWV was also intended to promote a routine point of contact over time, facilitating the development of a continuous relationship with a health-care provider.

The visit builds on the initial Welcome to Medicare visit and includes assessments of older adults’ health status, psychosocial risks (including depression screening), behavioral risks, cognitive functioning, physical functioning (i.e., ability to perform activities of daily living, fall risk, hearing impairment, and home safety), and biometric health indicators (e.g., body mass index and blood pressure; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2017). At the conclusion of the visit, a primary-care provider and his or her patient create a tailored plan for preventive health screenings, lifestyle interventions, and other wellness goals.

Evidence to date on the benefits of AWVs is limited and mixed. Two studies—one of a large, multi-specialty health system (Chung et al., 2015) and the other of five outpatient, community-based clinics (Galvin et al., 2017)—showed greater use of some routine and preventive services (e.g., advance directives, abdominal aortic aneurysm screening, mammography, vaccines) and decreased use of others (e.g., colorectal cancer screening, bone density scans). A third study at a large, multi-site provider network found no change in depression screening rates, despite such screening being a required element of the AWV (Pfoh, Mojtabai, Bailey, Weiner, & Dy, 2015). A fourth study, using national survey data, found no significant change in self-reported preventive service rates before or after the AWV introduction (Jensen, Salloum, Hu, Ferdows, & Tarraf, 2015). Further research is needed to examine the health effects of AWVs in the United States.

Current Trends in the Use of Medicare Annual Wellness Visits

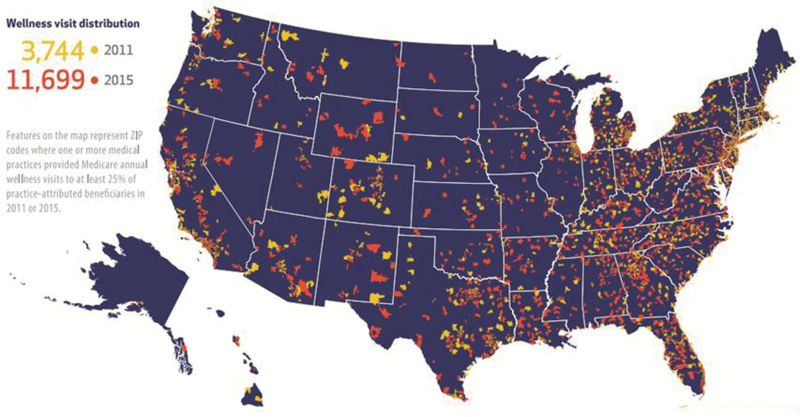

Since the introduction of the Medicare-covered benefit in 2011, the percentage of eligible beneficiaries receiving an AWV only increased from 7.5% in 2011 to 15.6% in 2014 and 18.8% in 2015 (Ganguli, Souza, McWilliams, & Mehrotra, 2017, 2018). There was also significant individual, practice-level, and regional variation in the AWV rates (Figure 2). Medicare beneficiaries were more likely to receive an AWV if they were White, female, lived in an urban or higher-income area, or had received the visit the year before. Practices participating in an accountable-care organization or the Medicare Electronic Health Record Incentive Program had higher rates of AWV use, as did practices with a larger proportion of primary-care physicians or more Medicare beneficiaries per primary-care physician (Ganguli et al., 2018).

Figure 2.

Distribution of annual wellness visit–adopting practices across the United States in 2015. The figure is from Ganguli, Souza, McWilliams, and Mehrotra (2018).

Using national Medicare data from 2008–2015, Ganguli and colleagues (2018) found that half of primary-care practices offered any AWVs. Lower AWV rates were noted among both underserved populations and the practices that cared for them. Eligible beneficiaries who were non-White, medically complex, or dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid (generally older adults with low incomes or those with disabilities) were less likely to receive a visit than other eligible beneficiaries in the same practice. In addition, practices that disproportionately cared for these historically-underserved populations were less likely to provide AWVs to any of their eligible beneficiaries.

To the extent that AWVs directly improve the health of seniors, these differences in AWV rates have the potential to worsen existing disparities for this population. In addition, physician practices that adopted AWVs have generated more revenue than non-adopters—in part because Medicare provides greater reimbursement for AWVs than for most traditional, problem-based medical visits—further widening resource gaps between the adopters and the non-adopters that disproportionately serve disadvantaged older adults (Ganguli et al., 2018).

Opportunities for Addressing Health Disparities Through Annual Wellness Visits

Underserved seniors who don’t receive an AWV may forego the potential benefits of the visit, such as increased engagement with their primary-care provider; identification of health risks, such as concerns for falls or depressed mood; counseling on health behaviors, including diet, exercise, or smoking cessation; and recommendations for preventive health services, such as cancer screenings and vaccinations.

A new approach to AWVs might encourage implementation by safety-net practices, such as federally-qualified health centers (FQHCs), and collaboration with Area Agencies on Aging (part of the national Aging Services Network, that assist with a wider variety of services for older adults in the community) in order to reach underserved seniors more effectively (O’Shaughnessy, 2008). As safety-net practices and local agencies frequently have limited resources, new models of AWVs should focus on enhancing activities already emphasized by such practices (Rosenblatt, Andrilla, Curtin, & Hart, 2006). Such activities would include assessments of older adults’ material resource needs (generally assessed by FQHCs to provide a sliding-fee scale) and connection to community-based supports and services, such as those provided by Area Agencies on Aging or other community-based organizations. To promote healthy aging for underserved populations, AWVs should focus on these issues, commonly encountered by vulnerable older adults. For example, while an assessment of fall risk and hearing impairment is certainly important for all older adults, low-SES Medicare beneficiaries may face additional barriers to health and health care, such as difficulty navigating transportation to medical visits, struggles with affording medications, or concerns about meeting basic needs, such as access to healthy food.

Screening for health-related social needs without addressing them may also contribute to patient stress (Garg, Boynton-Jarrett, & Dworkin, 2016). Therefore, screening for these issues should include appropriate referrals to community resources or to other skilled members of the health-care team.

Proposed Model for an Enhanced Annual Wellness Visit

To mitigate growing disparities in health and longevity for underserved seniors, we propose enhancing the traditional Medicare AWV by expanding screening and counseling for social determinants of health. This approach could include screening for behavioral health issues, such as anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorders, in addition to the depression screening already included in the traditional AWV. Screening for and addressing social determinants of health could go hand-in-hand with addressing cardiovascular risk factors that contribute to poor health among low-SES Medicare beneficiaries. At present, safety-net practices frequently consider social determinants of health when determining patient eligibility, but there is no uniform standard to guide which types of health-related social needs are screened for, which screening instruments are used, or how practices address identified needs in real time (Byhoff et al., 2017; Institute of Medicine, 2015).

Screening Tools

Several screening tools are available to assess multiple domains of social determinants of health and are currently being used by local and national organizations. One prime example is the Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences (PRAPARE) assessment tool, which was developed by the National Association of Community Health Centers (2018). This tool emphasizes social determinant measures that can be addressed in FQHCs or similar safety-net practices. PRAPARE core measures include race/ethnicity, education, income, employment, language, migrant status, veteran status, insurance status, socioeconomic status (including income, education, and employment), material resource needs (such as food or utilities), housing instability, transportation, neighborhood, stress, and social integration and support. Optional measures include assessments of home and neighborhood safety, domestic violence, refugee status, and incarceration history. The PRAPARE screening tool was developed and pilot tested in four states (Hawaii, Iowa, New York, and Oregon) before being disseminated in community health centers across the country; the tool shares similarities to other social determinant screening tools (LaForge et al., 2018; National Association of Community Health Centers, 2018). The PRAPARE developers have also created templates that can readily incorporate the tool into commonly-used electronic health record systems, such as Epic. Such electronic health record templates would ideally be interoperable across health-care systems. Initial pilot studies of electronic health record screening templates have demonstrated that they are feasible to implement (Gold et al., 2018).

In addition, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation in CMS recently initiated a broad, national experiment known as Accountable Health Communities, which emphasizes addressing social determinants of health in routine health care (Alley et al., 2016). CMS is spending $157 million over 5 years on this program, in which 32 organizations in 23 states are participating and conducting social interventions involving approximately 3 million patients annually (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2018; Gottlieb, Colvin, et al., 2017). Eligible patients are enrolled in Medicare and/or Medicaid coverage, including enrollees who receive care through managed-care organizations or accountable-care organizations. The program aims to link health-care systems with community services through hubs called “bridge organizations” that coordinate care for beneficiaries across health system and community settings. CMS has developed its own social determinant screening tool for the Accountable Health Communities participating sites, focusing on domains that could negatively impact health and health-care utilization (Billioux, Verlander, Anthony, & Alley, 2017). The tool includes 5 core domains (housing instability, food insecurity, transportation problems, utility needs, interpersonal safety) and 8 supplemental domains (financial strain, employment, family/community support, education, physical activity, substance use, mental health, disabilities), and is another model that could be incorporated into an enhanced AWV.

The two screening tools emphasize different items, with the PRAPARE tool focusing on identifying actionable needs and the Accountable Health Communities tool focusing on needs that can be associated with excess health-care utilization. At present, the PRAPARE tool may be easier to integrate into clinical workflows, as it has electronic health record templates, though electronic templates for the Accountable Health Communities tool may also be developed in the future.

Adding new requirements for AWVs comes with potential downsides, however. The current AWV’s complexity may have already contributed to low adoption, especially among safety-net practices that face greater patient complexity and workloads (Beran & Craft, 2015; Cuenca, 2012; Muldoon, Rayner, & Dahrouge, 2013). Therefore, CMS should couple expanded requirements for an enhanced AWV with greater flexibility in how practices implement expanded screening and linkage to resources, including which screening tools are selected.

Team Member Roles

To change practices for an enhanced AWV, it will be important to include all health-care team members, including nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurses, or health coaches, who can already perform AWVs within primary-care practices (Galvin et al., 2017). Practices might convene representative team members to develop new clinical workflows for enhanced screening and assign team member roles based on areas of expertise. For example, behavioral health screening may be performed by a social worker or mental health professional. Medical assistants or nurses may administer the multi-social determinant screening tool and document the findings in the electronic health record. Individual primary-care providers may review findings from the assessment and lead the team in creating a care plan for the patient that is tailored to their specific needs, resources, and supports.

Local agencies within the Aging Services Network could serve as a key potential partner for primary-care practices conducting an enhanced AWV. As individual, social, and behavioral needs are identified by practices, older adults may be referred to case managers in these local agencies to connect to resources. Area Agencies on Aging provide for a wide variety of services to support older adults in the community, including food assistance, transportation to services, legal assistance, personal care and caregiver support, and social support groups (O’Shaughnessy, 2008).

Another type of health-care worker that is growing in importance in safety-net clinics is the community health worker, a team member with expert knowledge of the patient’s community who serves as a liaison, connecting the patient to health and social services (American Public Health Association, 2018). Employing community health workers may be a cost-effective approach to implement an enhanced Medicare AWV in safety-net settings. Community health workers could partner with case managers in Area Agencies on Aging to provide comprehensive care that addresses social determinants of health and allows older adults to continue to live in their homes. Sustainable funding for community health workers will be fundamental to the success of their role in a new care model, and payment reforms will likely be needed to facilitate their recruitment, training, and continued employment as care team members.

Implementation of Best Practices

To implement the Enhanced AWV on a broad scale, challenges to practice transformation will need to be addressed. In creating the PRAPARE tool, for example, the National Association of Community Health Centers also developed an implementation toolkit that can be used by safety-net practices to incorporate new electronic health record templates, new workflows, and new roles for care team members. The toolkit is being updated over time and is freely available for download (National Association of Community Health Centers, 2018).

Policy Recommendations

To implement an enhanced AWV, the Medicare program should update its policies around required elements of the visit and the funding model supporting it. If the current demonstrations of the National Association of Community Health Centers’ PRAPARE tool or CMS’s Accountable Health Communities model prove successful, either of the social determinant screening tools developed could be suggested as core elements of the enhanced AWV. For efficiency’s sake, the screening tool should contain fewer than 10 elements and enhanced screening requirements should be broad and customizable to individual patient and practice needs, as noted above. The screening tool should also, ideally, have high validity and reliability in measurement.

To accommodate potential costs associated with the hiring of new care team members to both screen for and address social determinants of health, CMS should provide an enhanced payment for community health centers and similar safety-net practices that conduct enhanced AWVs, as these practices disproportionately serve older adults with greater social needs. An enhanced payment could also entice other safety-net practices, which are currently less likely to conduct traditional AWVs than practices serving more affluent older adults, to adopt enhanced AWVs.

Under the same paradigm as the Accountable Health Communities model, an Enhanced Medicare AWV would reflect “a growing emphasis on population health in CMS payment policy, which aims to support a transition from a health care delivery system to a true health system” (p. 11) (Alley et al., 2016). It also reflects a trend by CMS to coordinate programs across payers to improve health and lower costs. The new emphasis of the Accountable Health Communities model extends the established models of Medicaid wrap-around services and of the Aging Services Network to focus on addressing social determinants of health for vulnerable populations. Programming for addressing social determinants in the health-care setting should be coordinated across Medicare, Medicaid, and the Aging Services Network to efficiently direct funding toward addressing older adults’ individual, social, and behavioral needs.

Similar to evaluations of the Accountable Health Communities model and other demonstration programs being conducted by CMS, rigorous research is needed to assess the ideal modes of social determinant screening, as well as potential benefits and costs of current and future AWV models, with regard to quality of care and health outcomes. Ideally, evaluations would include experimental or quasi-experimental study designs and outcomes studied should include mediators of health disparities—such as cardiovascular risk factors and food insecurity—in addition to the overall health status of beneficiaries and program costs to CMS. In this way, policymakers and researchers can assess and refine the current and enhanced AWV models, as well as their payment mechanisms.

Conclusion

To reduce disparities in healthy aging faced by underserved seniors and the practices that care for them, the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit should be revamped to identify and address social determinants of health. In an enhanced AWV, Medicare beneficiaries would engage with primary-care teams to develop a tailored plan that moves beyond basic lifestyle counseling to identify and address social risk factors that contribute to health disparities. In this way, the enhanced AWV of the future may help to reduce disparities in healthy aging and longevity for the most vulnerable older adults.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institute of Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award number P01AG032952. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Alley D. E., Asomugha C. N., Conway P. H., & Sanghavi D. M (2016). Accountable health communities–addressing social needs through medicare and medicaid. The New England Journal of Medicine, 374, 8–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1512532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Public Health Association (2018). Community health workers Retrieved from https://www.apha.org/apha-communities/member-sections/community-health-workers [DOI] [PubMed]

- Beran M. S., & Craft C (2015). Medicare annual wellness visits. Understanding the patient and physician perspective. Minnesota Medicine, 98, 38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billioux A., Verlander K., Anthony S., & Alley D (2017). Standardized screening for health-related social needs in clinical settings: The accountable health communities screening tool Retrieved from https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Standardized-Screening-for-Health-Related-Social-Needs-in-Clinical-Settings.pdf

- Byhoff E., Cohen A. J., Hamati M. C., Tatko J., Davis M. M., & Tipirneni R (2017). Screening for social determinants of health in Michigan health centers. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine: JABFM, 30, 418–427. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2017.04.170079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A., & Deaton A (2015). Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among White non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112, 15078–15083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518393112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2017). The ABCs of the annual wellness visit (AWV) Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/AWV_chart_ICN905706.pdf

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2018). Accountable health communities model Retrieved from https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/ahcm/

- Chetty R., Stepner M., Abraham S., Lin S., Scuderi B., Turner N., … Cutler D (2016). The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. JAMA, 315, 1750–1766. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S., Lesser L. I., Lauderdale D. S., Johns N. E., Palaniappan L. P., & Luft H. S (2015). Medicare annual preventive care visits: use increased among fee-for-service patients, but many do not participate. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 34, 11–20. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca A. E.(2012). Making Medicare annual wellness visits work in practice. Family Practice Management, 19, 11–16. Retrieved from https://www.aafp.org/fpm/2012/0900/p11.html?printable=fpm [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. A., Guo C., Sol K., Langa K. M., & Nallamothu B. K (2017). Trends and disparities in the number of self-reported healthy older adults in the United States, 2000 to 2014. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(11), 1683–1684. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin S. L., Grandy R., Woodall T., Parlier A. B., Thach S., & Landis S. E (2017). Improved utilization of preventive services among patients following team-based annual wellness visits. North Carolina Medical Journal, 78, 287–295. doi: 10.18043/ncm.78.5.287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli I., Souza J., McWilliams J. M., & Mehrotra A (2017). Trends in use of the US Medicare Annual Wellness Visit, 2011-2014. JAMA, 317(21), 2233–2235. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.4342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli I., Souza J., McWilliams J. M., & Mehrotra A (2018). Practices caring for the underserved are less likely to adopt Medicare’s Annual Wellness Visit. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 37, 283–291. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg A., Boynton-Jarrett R., & Dworkin P. H (2016). Avoiding the unintended consequences of screening for social determinants of health. JAMA, 316, 813–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.9282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold R., Bunce A., Cowburn S., Dambrun K., Dearing M., Middendorf M., … Cottrell E (2018). Adoption of social determinants of health EHR tools by community health centers. Annals of Family Medicine, 16, 399–407. doi: 10.1370/afm.2275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb L., Ackerman S., Wing H., & Manchanda R (2017). Understanding Medicaid managed care investments in members’ social determinants of health. Population Health Management, 20(4), 302–308. doi: 10.1089/pop.2016.0092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb L., Colvin J. D., Fleegler E., Hessler D., Garg A., & Adler N (2017). Evaluating the accountable health communities demonstration project. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32, 345–349. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3920-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb L. M., Garcia K., Wing H., & Manchanda R (2016). Clinical interventions addressing nonmedical health determinants in Medicaid managed care. The American Journal of Managed Care, 22, 370–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiss F., Venti S. F., & Wise D. A (2014). The persistence and heterogeneity of health among older Americans Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w20306

- Institute of Medicine (2015). Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures in Electronic Health Records: Phase 2. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/18951 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen G. A., Salloum R. G., Hu J., Ferdows N. B., & Tarraf W (2015). A slow start: Use of preventive services among seniors following the Affordable Care Act’s enhancement of Medicare benefits in the U.S. Preventive Medicine, 76, 37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S. R. (2018). Hospitals address social determinants of health through community cooperation and partnerships. Modern Healthcare. Retrieved from http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20180602/TRANSFORMATION03/180609978

- LaForge K., Gold R., Cottrell E., Bunce A. E., Proser M., Hollombe C., … Clark K. D (2018). How 6 organizations developed tools and processes for social determinants of health screening in primary care: An overview. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 41, 2–14. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meara E. R., Richards S., & Cutler D. M (2008). The gap gets bigger: Changes in mortality and life expectancy, by education, 1981-2000. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 27, 350–360. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muldoon L., Rayner J., & Dahrouge S (2013). Patient poverty and workload in primary care: study of prescription drug benefit recipients in community health centres. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 59, 384–390. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2015). The growing gap in life expectancy by income. implications for federal programs and policy responses Retrieved from https://www.nap.edu/catalog/19015/the-growing-gap-in-life-expectancy-by-income-implications-for

- National Association of Community Health Centers (2018). PRAPARE implementation and action toolkit Retrieved from http://www.nachc.org/research-and-data/prapare/toolkit/

- Odutayo A., Gill P., Shepherd S., Akingbade A., Hopewell S., Tennankore K., … Emdin C. A (2017). Income disparities in absolute cardiovascular risk and cardiovascular risk factors in the United States, 1999-2014. JAMA Cardiology, 2, 782–790. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.1658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olshansky S. J., Antonucci T., Berkman L., Binstock R. H., Boersch-Supan A., Cacioppo J. T., … Rowe J (2012). Differences in life expectancy due to race and educational differences are widening, and many may not catch up. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 31, 1803–1813. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shaughnessy C. (2008). The aging services network: accomplishments and challenges in serving a growing elderly population. Retrieved from https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/sphhs_centers_nhpf/196/

- Pfoh E., Mojtabai R., Bailey J., Weiner J. P., & Dy S. M (2015). Impact of medicare annual wellness visits on uptake of depression screening. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 66(11), 1207–1212. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt R. A., Andrilla C. H., Curtin T., & Hart L. G (2006). Shortages of medical personnel at community health centers: implications for planned expansion. JAMA, 295, 1042–1049. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeni R. F., Martin L. G., Andreski P. M., & Freedman V. A (2005). Persistent and growing socioeconomic disparities in disability among the elderly: 1982-2002. American Journal of Public Health, 95, 2065–2070. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.048744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldo B. J., Mitchell O. S., Tfaily R., & McCabe J. F (2006). Cross-cohort differences in health on the verge of retirement Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w12762

- Tipirneni R. L., & Langa K. M. (2018). A key challenge for Medicare’s annual wellness visits: spreading the benefits to underserved seniors Retrieved from https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180213.276024/full/

- Wilensky G. R., & Satcher D (2009). Don’t forget about the social determinants of health. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 28, w194–w198. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.w194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]