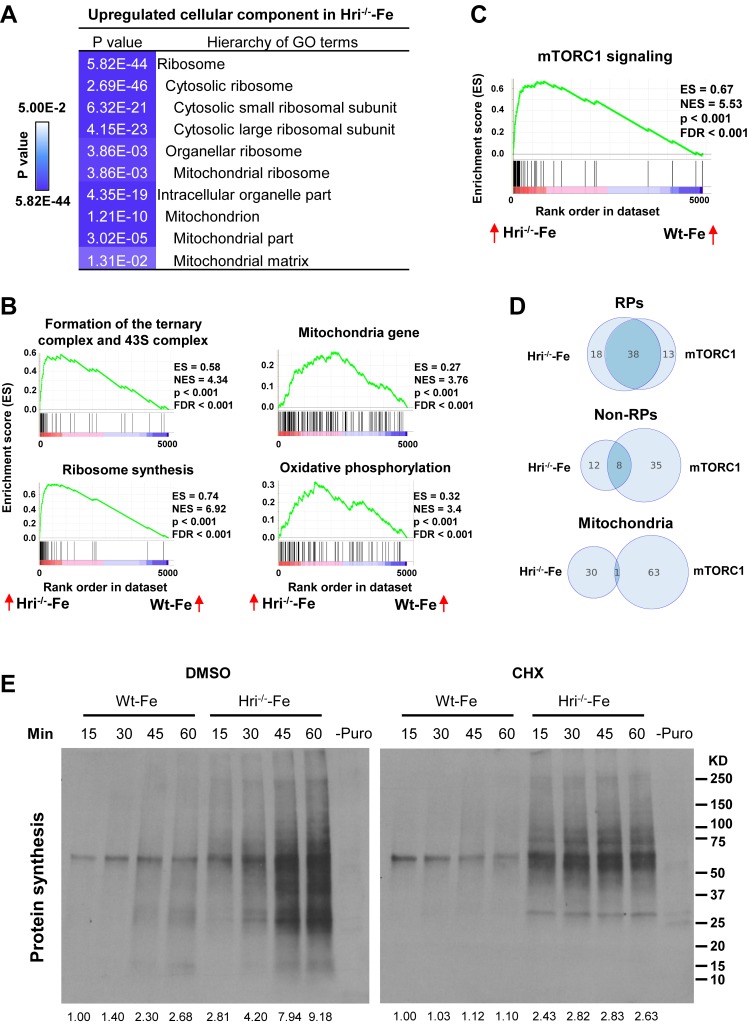

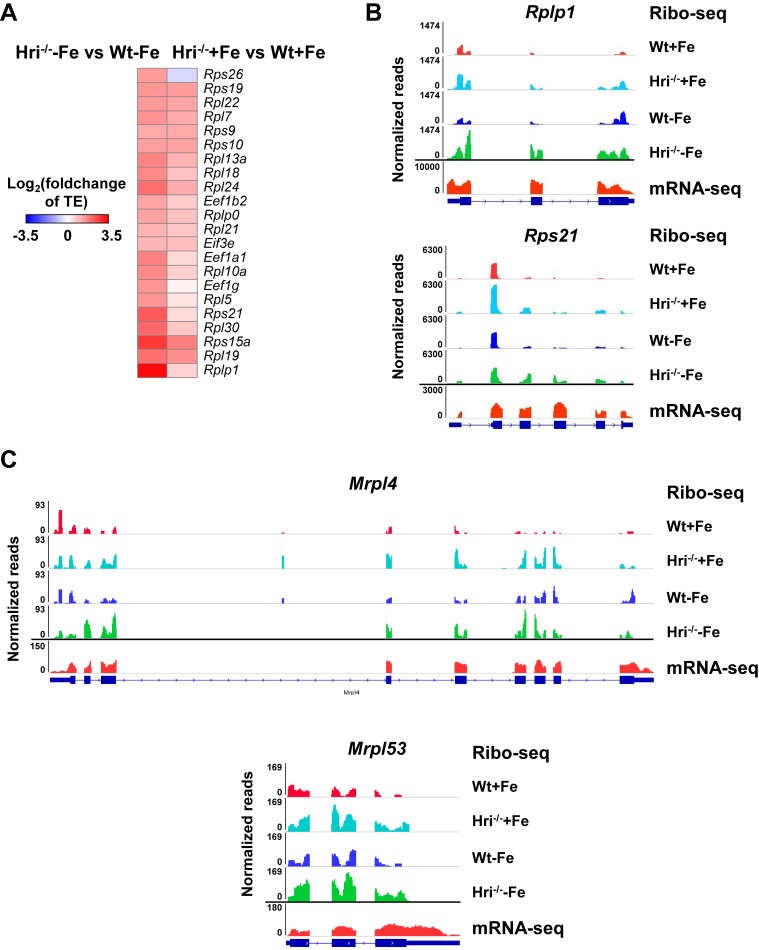

Figure 3. Analyses of the mRNAs that are differentially translated between Wt and Hri–/– EBs.

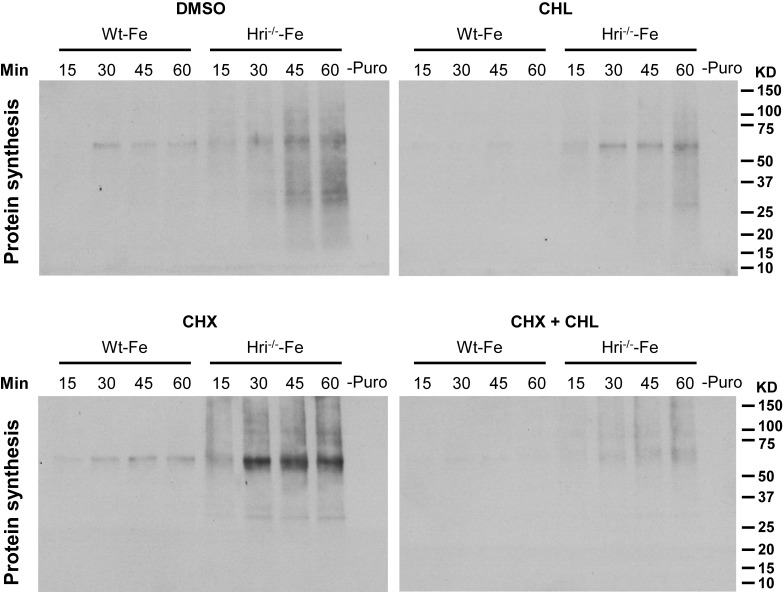

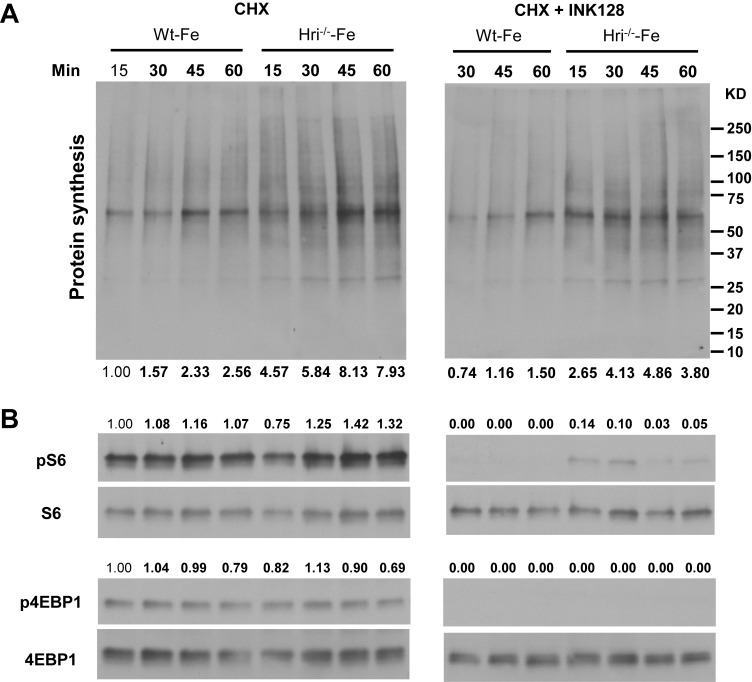

(A) GO analysis of the most highly translated mRNAs in Hri-/– –Fe EBs compared to Wt –Fe EBs. (B) Increased 43S initiation complex, ribosomal protein (RP) synthesis and mitochondrial pathways in Hri–/– –Fe EBs compared to Wt –Fe EBs by Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. (C) Increased mTORC1 signaling pathway in Hri–/– –Fe EBs compared to Wt –Fe EBs. (D) Venn diagrams comparing mRNAs that are differentially translated in Hri–/– –Fe EBs and Wt –Fe EBs, and that are known mTORC1 targets in the categories of RPs, non-RPs and mitochondrial proteins. (E) Protein synthesis (total (left) and in mitochondria (right)) of erythroid cells from the bone marrow (BM) of Wt –Fe and Hri–/– –Fe mice. Cells were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or cycloheximide (CHX) for 15 min before the addition of puromycin for 15–60 min as indicated. Protein synthesis was determined by the nascent polypeptides covalently linked by puromycin using anti-puromycin antibody. Equal numbers of nucleated cells were loaded to each lane. The numbers of cells loaded for cytoplasmic protein synthesis were 30% of those loaded for mitochondrial protein synthesis. The results shown are from the same exposure time for developing the Western blot. Puromycin signals from polypeptides of the entire lane were quantified for protein synthesis activity and the protein synthesis in the first lane was define as 1. –Puro indicates cells without puromycin treatment, which were used as a negative control for Western signals from anti-puromycin antibody. FDR, false discovery rate; NES, normalized enrichment score.