Abstract

Orexins/hypocretins are neuropeptides implicated in numerous processes, including food intake and cognition. The role of these peptides in the psychopathology of anorexia nervosa (AN) remains poorly understood. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the associations between plasma orexin-A (OXA) concentrations and neuropsychological functioning in adult women with AN, and a matched control group. Fasting plasma OXA concentrations were taken in 51 females with AN and in 51 matched healthy controls. Set-shifting was assessed using the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), whereas decision making was measured using the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT). The AN group exhibited lower plasma OXA levels than the HC group. Lower mean scores were obtained on the IGT in AN patients. WCST perseverative errors were significantly higher in the AN group compared to HC. In both the AN and HC group, OXA levels were negatively correlated with WCST non-perseverative errors. Reduced plasma OXA concentrations were found to be associated with set-shifting impairments in AN. Taking into consideration the function of orexins in promoting arousal and cognitive flexibility, future studies should explore whether orexin partly underpins the cognitive impairments found in AN.

Subject terms: Psychiatric disorders, Endocrine system and metabolic diseases, Cognitive neuroscience

Introduction

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a psychiatric disorder characterized by low body weight, severely restricted eating behavior, an extreme pursuit of thinness and an intense fear of weight gain1. In addition to the above-mentioned symptoms, patients with AN have repeatedly been found to present altered performance on neuropsychological tasks examining decision-making2,3, set-shifting4, central coherence5, and delay discounting6,7. There is also strong evidence to support that alterations in reward processing in AN patients are underpinned by altered reactivity in striatal regions8 and to the possibility of hypothalamic inputs being overridden by top-down emotional-cognitive control regions9. Additionally, innovative new lines of research suggest that increased activations in fronto-striatal circuits are strongly associated with the maintenance of restrictive eating habits in AN patients10. These deficits in executive functioning are thought to contribute to the severity of the disorder and hinder the effectiveness of treatment by encouraging reduced food intake, body image distortions, and rigid thinking styles11. Indeed, recent findings indicate that the undernourished state of AN may amplify the tendency to forgo immediate rewards in favor of longer-term goals, thereby perpetuating the symptoms of AN12.

Orexin-A (OXA), also known as hypocretin 1, is a neuropeptide synthesized in the hypothalamus that is implicated in the regulation of an array of complex behaviors, including sleep/wakefulness, reward, food intake, and cognition13–16. Although OXA neurons were until recently thought to be restricted to the lateral hypothalamus, studies have found that orexinergic fibers are extensively distributed in numerous brain regions, including the posterior hypothalamus and perifornical areas17. Orexins are increasingly understood to play a significant role in the pathology of psychiatric disorders18, narcolepsy-cataplexy19, neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease20, and in controlling energy homeostasis21,22. In the specific case of AN, results thus far have been inconsistent with studies finding plasma OXA levels in patients with AN to be higher23, lower24, or not significantly different in comparison to healthy controls (HC)25. Though few longitudinal studies have carried out in AN patients, it appears that OXA levels decrease following weight restoration23,24. However, it must be noted that these studies had relatively small sample sizes and did not follow patients for a long enough time span for full recovery to be reached. OXA levels in AN patients may also potentially be influenced by the diurnal intermittent fasting that is characteristic of the disorder26. Such fluctuations in OXA concentrations could have downstream effects on wakefulness14 and response to salient cues27, thereby influencing executive functioning.

Orexins are believed to be involved in higher cognitive functions due to their role in maintaining the excitability of pyramidal neurons in the prefrontal cortex18. One study determined elevated orexins in female rats following repeated exposure to stress to be linked to stress-induced cognitive deficits in the side reversal task of Attentional Set Shifting Test28. Likewise, the preclinical literature has consistently suggests that orexins enhance cognitive function, whereas orexin antagonists lead to impairments in different types of cognitive function, such as attention, spatial memory, and social memory29. Taking into consideration the aforementioned importance of cognition in treatment response, it would be of great interest to determine the associations between neurocognitive performance and OXA levels in patients with AN. Such findings could shed light on the emerging role of the orexinergic system in the pathophysiology of AN30.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Participants in this study included 51 women with AN (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) and 51 matched female healthy controls (HC; BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2). 65.8% of the sample included in this study was featured in Sauchelli et al.25. AN participants were consecutively recruited from the Department of Psychiatry at Bellvitge University Hospital (Barcelona, Spain) and were diagnosed by means of structured face-to-face interview, following DSM-5 criteria31. All diagnoses were established using an adapted version of the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I)32.

Participants were excluded if they were under 18 or over 60 years of age. Males were excluded from the study given the low prevalence of male AN patients in our sample. Several centers belonging to our Spanish Research Network (CIBEROBN) participated in this project. The HC group was a convenience sample (matched for age and education level) recruited via word-of-mouth and advertisements. To be eligible for the HC group, participants could not have a lifetime history of an eating disorder and current obesity.

As described previously16,25, clinical and physical assessments were conducted by experienced psychologists, psychiatrists and endocrinologists. Self-report questionnaires were completed as part of the evaluation process at the start of treatment. Patients with AN were voluntarily undergoing day-hospital treatment and all measures were collected upon admission to treatment. All participants completed the same self-reported questionnaires to coincide with the blood sample extraction. Anthropometric information was obtained using a bioimpedance scale.

All participants provided signed informed consent. The University Hospital of Bellvitge Ethics Committee of Clinical Research, the Hospital Universitari de Girona Doctor Josep Trueta Comitè Ètic d’Investigació Clínica, the Parc de Salut Mar Comitè Ètic d’Investigació Clínica, the Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria Subcomisión de Investigación Clínica, Universidad de Navarra Comité de Ética de la Investigación, and the Comissió Deontológica de la Universitat Jaume 1 approved the study, conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measures

Orexin-A plasma concentrations

Peripheral blood samples were collected from all participants after an overnight fast. Blood was drawn from an antecubital vein using a 10 mL ethylenediamietraacetic acid (EDTA) containing BD Vacutainer® tube. Samples were centrifuged at 3130 × g for 15 min at 4 degrees Celsius (°C). Plasma and serum were distributed in aliquots and stored at 80 (°C) until analysis. Several plasma bio-chemical variables were measured in duplicate. OXA/hypocretin-1 was measured using a Phoenix Pharmaceuticals Inc. EIA kit (Burlingame, California, USA). Multiple studies have demonstrated that it features a wide detection range, between 0–100 ng/mL, with a linear range of 0.2–2.66 ng/mL, a sensitivity of 0.2 ng/ml, an intra-assay variation <10%, and an inter-assay variation <15%. Our data provide a linear range of 0.30–3.08 ng/mL, a detection limit of 0.16 ng/ml, an intra-assay variation of 9.52% and an inter-assay variation of 13.70%. With respect to its specificity, this kit does not have cross-reactivity with OXA (16–33), orexin B (human), agouti-related protein (83–132)-amide (human), neuropeptide (human, rat), α-MSH (human, rat, mouse) and leptin (human). We did not analyze cross-reactivity with any other molecule.

Anthropometric measures

A Tanita BC-420MA was utilized to measure body composition and to calculate BMI. This noninvasive and validated device (Tanita BC-420MA) uses bioelectrical impedance analyses to obtain weight and body composition variables33. Height was taken via a stadiometer.

The Wisconsin card sorting test (WCST)

The WCST34 is a widely used measure to assess an individual’s capacity to plan, control impulsive responses, and be flexible under changing conditions. During this task, participants must match a target card with one of four category cards. After each trial, feedback is given to the participant, indicating whether they have matched the card appropriately. However, the classification rule for matching cards with categories changes during the task and participants must shift and update their previous strategy to perform well on the task. The test ends when the participant has completed six categories or 128 trials. A computerized version of the task was used for this study35.

The iowa gambling task (IGT)

The IGT36,37 is a commonly used measure of decision-making ability. During this task, participants must choose from four decks of cards (A, B, C and D) and each time the participant selects a deck, a specified amount of play money is awarded. The interspersed rewards among theses decks feature probabilistic punishments (monetary losses with varying amounts). Decks A and B are not advantageous as losses are higher than gains; whereas, decks C and D are advantageous since the punishments are smaller. This test is scored by subtracting the number of cards selected from decks A and B from the number of cards selected from decks C and D. Higher scores demonstrate better performance on the task while negative scores are indicative of choosing disadvantageous decks.

General psychopathology

The Symptom Checklist-revised (SCL-90-R)38 was used to explore general psychopathology. This 90-item, self-report questionnaire is answered on a five-point Likert scale. The items are grouped into nine primary symptom dimensions and it provides a global severity index (GSI) to indicate overall distress. The test has been validated in a Spanish population39, with a mean internal consistency of 0.75 (alpha coefficient).

Eating disorder symptomatology

The Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI-2)40 was used to examine eating disorder severity. This test, consisting of 91 items, each rated on a six-point Likert scale, evaluates eleven cognitive and behavioral characteristics observed in people with eating disorders. A total score is also provided to report overall eating disorder severity. This instrument has been validated in Spanish-speaking populations41 with a mean internal consistency of 0.63 (alpha coefficient).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out with Stata15 for Windows. Comparisons of means between groups (AN and HC) was based on analysis of variance (ANOVA). Associations between neuropsychological variables and orexin levels were estimated with correlation coefficients. In this study, due to the strong association between neuropsychological performance with age and education levels, these two variables were defined as covariates in the statistical analysis. Effect size was measured through Cohen’s-d coefficient for mean differences (|d| > 0.2 was considered low effect size, |d| > 0.5 was considered moderate and |d| > 0.8 was considered large)42. For the correlation estimates, and due to the strong association between this model and sample size, relevance was based on coefficient measures (|R| > 0.10 was considered low effect size, |r| > 0.24 was considered moderate and |r| > 0.37 was considered large)43. Finner’s method controlled for increases in Type-I error due to multiple statistical comparisons (this procedure is included in the Family-wise error rate stepwise procedures and provides a more powerful test than Bonferroni correction)44.

Results

Sample description and comparison between OXA, body composition and neuropsychological measures

Table 1 contains a description of the study variables, as well as comparisons between the groups. As mentioned above, HC were chosen to match their AN counterparts with respect to age and years of education and no differences were found between groups in these variables (p = 0.666 and p = 1.000, respectively). As expected, patients with AN exhibited significantly higher levels of psychopathology as measured by the SCL-90-R GSI score and higher levels of total eating disorder severity on the EDI-2.

Table 1.

Sample description and comparison between groups in orexin levels, body composition and neuropsychological performance.

| Anorexia (n = 51) | Control (n = 51) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p | |d| | |

| Age (years) | 27.43 | 8.65 | 26.75 | 7.32 | 0.666 | 0.09 |

| EDI-2 total score | 78.78 | 43.72 | 22.59 | 16.91 | 0.001* | 1.70† |

| SCL-90-R GSI | 1.48 | 0.74 | 0.56 | 0.39 | 0.001* | 1.56† |

| Plasma orexin-A levels (pg/ml) | 2.43 | 0.82 | 2.99 | 0.67 | 0.001* | 0.75† |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 17.11 | 1.27 | 21.37 | 1.81 | 0.001* | 2.73† |

| Body fat mass (%) | 6.37 | 3.11 | 15.32 | 4.42 | 0.001* | 2.34† |

| 1IGT Block 1 (raw score) | −1.95 | 4.20 | −2.44 | 7.48 | 0.714 | 0.08 |

| 1IGT Block 2 (raw score) | −0.77 | 4.41 | 5.69 | 8.35 | 0.001* | 0.97† |

| 1IGT Block 3 (raw score) | −0.20 | 5.36 | 7.01 | 8.48 | 0.001* | 1.02† |

| 1IGT Block 5 (raw score) | 0.42 | 6.69 | 9.30 | 9.28 | 0.001* | 1.10† |

| 1IGT Block 6 (raw score) | 0.79 | 9.26 | 6.80 | 10.61 | 0.007* | 0.60† |

| 1IGT Total (raw score) | −1.71 | 21.06 | 26.36 | 27.82 | 0.001* | 1.14† |

| 1WCST Trials (raw score) | 92.51 | 18.05 | 86.96 | 16.32 | 0.182 | 0.32 |

| 1WCST Correct (raw score) | 65.67 | 12.39 | 66.98 | 6.92 | 0.547 | 0.13 |

| 1WCST Errors (raw score) | 26.91 | 17.19 | 19.99 | 17.52 | 0.152 | 0.40 |

| 1WCST perseverative errors (raw score) | 13.57 | 9.87 | 9.53 | 5.22 | 0.045* | 0.51† |

| 1WCST non-perseverative errors (raw score) | 13.33 | 16.99 | 10.46 | 11.41 | 0.350 | 0.20 |

| 1WCST conceptual (raw score) | 57.90 | 18.90 | 61.76 | 11.33 | 0.250 | 0.25 |

Note. 1Results adjusted for age and education level. SD: standard deviation.

*Bold: significance (0.05 level). †Effect size in the moderate (|d| > 0.50) to high range (|d| > 0.80).

p-value includes Finner’s correction for multiple statistical comparisons.

EDI-2: The Eating Disorder Inventory-2; SCL-90-R: The Symptom Checklist-revised; BMI: body mass index; IGT: Iowa Gambling Task; WCST: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test.

Table 1 also contains the results of the ANOVA, adjusted for age and education level, comparing the mean scores between the groups. The AN group exhibited lower BMI and body fat mass % than the HC group. Lower means were obtained on all the IGT measures (except for block 1) in AN patients. WCST perseverative errors were significantly higher in the AN group compared to HC.

Correlation analysis

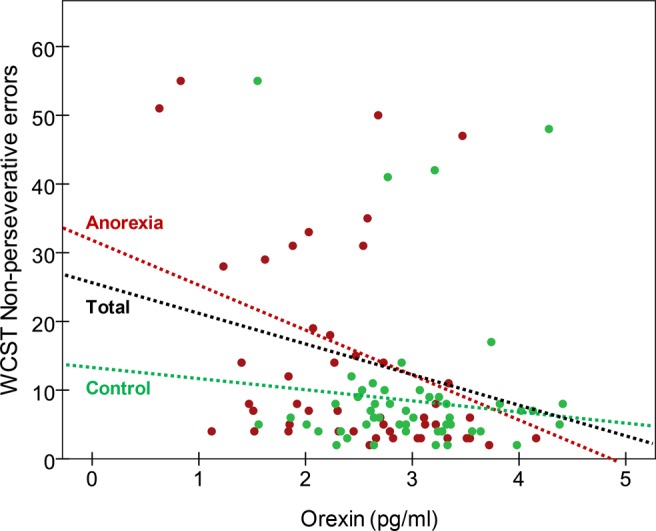

Table 2 contains the partial correlation matrix (coefficients adjusted for age, education and BMI) measuring the association between the neuropsychological measures and plasma OXA levels. Taking into account previous studies indicating an association between clinical state and neuropsychological performance2, we chose to run our correlational analyses including BMI as a covariate. Negligible differences in the results were found when BMI was not included as a covariate. In the AN group, OXA levels were negatively correlated with IGT block 1 performance, WCST number of trials, WCST errors and WCST non-perseverative errors. In the HC group, OXA levels were positively correlated with IGT block 4 scores and negatively correlated with WCST non-perseverative errors. Figure 1 presents a scatterplot of OXA levels and WCST non-perseverative errors in both groups and the whole sample. Regarding the potential associations between the measures of ED severity (EDI-2 total raw scores) and psychopathology (SCL-90R GSI) with OXA levels, the bottom of the Table 2 contains these partial correlations, whose effect sizes were in the low/null range.

Table 2.

Associations between neuropsychological measures with orexin levels (pg/ml): partial correlations (adjusted for age, education level and BMI).

| Anorexia (n = 51) | Control (n = 51) | |

|---|---|---|

| IGT Block 1 (raw score) | −0.331† | −0.097 |

| IGT Block 2 (raw score) | 0.089 | 0.142 |

| IGT Block 3 (raw score) | 0.104 | 0.205 |

| IGT Block 4 (raw score) | 0.080 | 0.241† |

| IGT Block 5 (raw score) | 0.136 | 0.175 |

| IGT Total (raw score) | 0.060 | 0.226 |

| WCST Trials | −0.300† | −0.206 |

| WCST Correct | −0.041 | 0.088 |

| WCST Errors | −0.241† | −0.227 |

| WCST perseverative errors | 0.014 | −0.172 |

| WCST Non-perseverative errors | −0.371† | −0.246† |

| WCST Conceptual | 0.126 | 0.200 |

| EDI-2 total score | 0.068 | 0.021 |

| SCL-90-R GSI | 0.078 | −0.027 |

Note. †Effect size in the moderate (|r| > 0.24) to high range (|r| > 0.37).

IGT: Iowa Gambling Task; WCST: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test.

Figure 1.

Scatterplot for orexin-A plasma levels (pg/ml) with WCST non-perseverative errors.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the association between OXA levels and cognitive impairments in patients with AN. Our findings indicate that OXA levels in AN patients were significantly lower than in HCs, though, it should be noted that diverging results in other AN samples have been found23. These discrepancies could stem from the numerous differences in the characteristics of the patients featured in the study at hand and other studies. For example, our study included patients with both AN restrictive subtype and binge-eating/purging subtype. One study utilizing an animal model of binge eating found that orexin antagonists reduced binge eating episodes preceded by stress and dietary restriction, suggesting that orexin could play distinctive role in AN patients that binge eat45. Other potential confounding factors include the effects of intermediate fasting26, sleep patterns46, and pharmacological treatment47. Recent research has also illustrated how insufficient up-regulation of orexin (Hcrt) genes during activity-based anorexia contributes to greater suppression of food intake and greater body weight loss in prenatal stress (PNS) exposed rats. This suggests that OXA may be useful for the discovery of biomarkers of weight loss vulnerability in order to gain a better understanding of neural circuits implicated in AN pathology30,48. Still, longitudinal studies are needed to determined whether such alterations in OXA are present before the onset of AN and after long-term recovery.

We also identified a significant correlation between non-perseverative errors on the WCST and orexin levels in both the AN and HC group. Non-perseverative errors are indicative of an inability to discern patterns and detect favorable choice. Our finding dovetails with the results of a recent study demonstrating that intra-basal forebrain infused OXA facilitated both the acquisition and reversal portions of an olfactory discrimination task49. Similarly, increased levels of OXA have been linked to fewer perseverative errors and reduced negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia50 compared to patients with lower orexin levels. Taking into consideration the function of orexins in promoting arousal and responding to stress, it could be posited that reduced OXA activity could partly underpin the cognitive impairments found in AN51,52.

In line with past research, we also identified decision-making deficits in patients with AN using the IGT2,3. Poor decision-making is known to be more pronounced during the acute phase than in the recovered state of AN2 and it would be of interest to explore whether such improvements coincide with changes in OXA levels. In the study at hand, OXA levels only negatively correlated with scores from the first block of the task in AN patients, but not with overall performance. Other studies have attempted to use intranasal administration of orexin peptides for age-related cognitive dysfunction53 and it may be of clinical interest to explore the possibility of using OXA to potentially offset the cognitive deficits found in certain psychiatric disorders54 or accompanying aging55. However, more basic research would be needed before such an endeavor could be undertaken.

This study must be interpreted in light of its limitations. For instance, diverging reports of increased or decreased levels of OXA in AN may result from sample heterogeneity (i.e. AN subtype, age and weight status). Another potential limitation of our study is the use of measured plasma OXA levels as a proxy for central orexin system activity. There is evidence in rodent studies to infer that OXA crosses the blood brain barrier56,57 and that the OXA plasma levels in humans are indicative of peptide release from both the brain and the gut58. However, no direct measure of CNS orexin levels were taken due to the high levels of invasiveness this procedure would entail. The kit used in this study could have other cross-reactivity than those mentioned by manufacturer. In this sense, we have not analyzed cross-reactivity with other molecules. However, our study does not intend to analyze this factor nor be a validation study of a kit that is already on the market and that has been widely used in other studies. Furthermore, no conclusions regarding causality can be made from our findings given the cross-sectional nature of our study. There is previous research to support that orexin levels could may in fact further decrease with treatment23,24, and it would be useful to examine orexin levels in individuals who have obtained full recovery from AN. Lastly, recent work has identified that orexins are regulators of sex differences in the behavioral adaptations to- and consequences of repeated stress28. Therefore, it would be beneficial for future studies to assess sex-related differences in orexin system functioning in patients with AN.

Acknowledgements

We thank CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya for institutional support. This manuscript and research was supported by grants from the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (PSI2015-68701-R), Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad (PR338/17), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) (FIS PI14/00290 and PI17/01167) and co-funded by FEDER funds/European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), a way to build Europe. CIBERObn and CIBERSAM are both initiatives of ISCIII. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. This research was supported by a PNSD (PR338/17-MSSSI) grant. GMB is supported by a predoctoral AGAUR grant (2018 FI_B2 00174), grant co-funded by the European Social Fund (ESF) “ESF”, investing in your future. With the support of the Secretariat for Universities and Research of the Ministry of Business and Knowledge of the Government of Catalonia. CVA is supported by a predoctoral Grant of the Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte (FPU16/01453). ABC is funded by a research contract “Miguel Servet” (CP17/00088) from the ISCIII.

Author Contributions

S.S., S.J.M., J.C.F.G., L.G.S., F.J.T., F.F.C., R.M.B., C.B., A.B.C., R.T., J.M.F.R., G.F., F.J.O., A.R., J.M.M. and F.F.A. designed the experiment based on previous results and the clinical experience of I.S. and N.R. T.S., G.M.B., R.G., F.F.A., C.V.A. and Z.A. conducted the experiment, analysed the data, and wrote a first draft of the manuscript. T.S., G.M.B. and C.V.A. further modified the manuscript and revised the manuscript following review.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association (2013).

- 2.Steward T, et al. Enduring Changes in Decision Making in Patients with Full Remission from Anorexia Nervosa. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2016;24:523–527. doi: 10.1002/erv.2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guillaume S, et al. Impaired decision-making in symptomatic anorexia and bulimia nervosa patients: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2015;45:3377–91. doi: 10.1017/S003329171500152X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith KE, Mason TB, Johnson JS, Lavender JM, Wonderlich SA. A systematic review of reviews of neurocognitive functioning in eating disorders: The state-of-the-literature and future directions. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018;51:798–821. doi: 10.1002/eat.22929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herbrich L, Kappel V, van Noort BM, Winter S. Differences in set-shifting and central coherence across anorexia nervosa subtypes in children and adolescents. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2018;26:499–507. doi: 10.1002/erv.2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steward T, et al. Delay Discounting of Reward and Impulsivity in Eating Disorders: From Anorexia Nervosa to Binge Eating Disorder. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2017;25:601–606. doi: 10.1002/erv.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinglass JE, et al. Temporal discounting across three psychiatric disorders: Anorexia nervosa, obsessive compulsive disorder, and social anxiety disorder. Depress. Anxiety. 2017;34:463–470. doi: 10.1002/da.22586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank GKW, et al. Association of Brain Reward Learning Response with Harm Avoidance, Weight Gain, and Hypothalamic Effective Connectivity in Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:1071–1080. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steward T, Menchon JM, Jimenez-Murcia S, Soriano-Mas C, Fernandez-Aranda F. Neural network alterations across eating disorders: a narrative review of fMRI studies. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018;16:1150–1163. doi: 10.2174/1570159X15666171017111532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foerde K, Steinglass JE, Shohamy D, Walsh BT. Neural mechanisms supporting maladaptive food choices in anorexia nervosa. Nature Neuroscience. 2015;18:1571–1573. doi: 10.1038/nn.4136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrison A, et al. Cognitive remediation therapy for adolescent inpatients with severe and complex anorexia nervosa: A treatment trial. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2018;26:230–240. doi: 10.1002/erv.2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Decker JH, Figner B, Steinglass JE. On weight and waiting: Delay discounting in anorexia nervosa pretreatment and posttreatment. in. Biological Psychiatry. 2015;78:606–614. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakurai T, et al. Orexins and orexin receptors: A family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92:573–585. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Lecea L, et al. The hypocretins: Hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:322–327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakurai T. The role of orexin in motivated behaviours. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014;15:719–31. doi: 10.1038/nrn3837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sauchelli S, et al. Interaction Between Orexin-A and Sleep Quality in Females in Extreme Weight Conditions. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2016;24:510–517. doi: 10.1002/erv.2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore RY, Abrahamson EA, Van Den Pol A. The hypocretin neuron system: An arousal system in the human brain. Arch. Ital. Biol. 2001;139:195–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Q, de Lecea L, Hu Z, Gao D. The hypocretin/orexin system: an increasingly important role in neuropsychiatry. Med. Res. Rev. 2015;35:152–97. doi: 10.1002/med.21326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peyron C, et al. A mutation in a case of early onset narcolepsy and a generalized absence of hypocretin peptides in human narcoleptic brains. Nat. Med. 2000;6:991–7. doi: 10.1038/79690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liguori C, et al. Orexinergic System Dysregulation, Sleep Impairment, and Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:1498. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernø J, Señarís R, Diéguez C, Tena-Sempere M, López M. Orexins (hypocretins) and energy balance: More than feeding. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015;418:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martins L, et al. A Functional Link between AMPK and Orexin Mediates the Effect of BMP8B on Energy Balance. Cell Rep. 2016;16:2231–2242. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bronsky J, et al. Changes of orexin A plasma levels in girls with anorexia nervosa during eight weeks of realimentation. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2011;44:547–52. doi: 10.1002/eat.20857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janas-Kozik M, et al. Plasma levels of leptin and orexin A in the restrictive type of anorexia nervosa. Regul. Pept. 2011;168:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sauchelli S, et al. Orexin and sleep quality in anorexia nervosa: Clinical relevance and influence on treatment outcome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;65:102–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Almeneessier A, et al. The effects of diurnal intermittent fasting on the wake-promoting neurotransmitter orexin-A. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2018;13:48. doi: 10.4103/atm.ATM_181_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi DL, Davis JF, Fitzgerald ME, Benoit SC. The role of orexin-A in food motivation, reward-based feeding behavior and food-induced neuronal activation in rats. Neuroscience. 2010;167:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grafe LA, Cornfeld A, Luz S, Valentino R, Bhatnagar S. Orexins Mediate Sex Differences in the Stress Response and in Cognitive Flexibility. Biol. Psychiatry. 2017;81:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grafe LA, Bhatnagar S. Orexins and stress. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2018;51:132–145. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berner, L. A. et al. Neuroendocrinology of reward in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: Beyond leptin and ghrelin. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 10.1016/j.mce.2018.10.018 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington D. C.: American Psychiatric Association (2013).

- 32.First, M. B., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. W. User’s guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I Disorders—Research version. (1996).

- 33.Browning LM, et al. Measuring Abdominal Adipose Tissue: Comparison of Simpler Methods with MRI. Obes. Facts. 2011;4:9–15. doi: 10.1159/000324546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heaton, R. K. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Manual. (Psychological Assessment Resources, 1981).

- 35.Lezak, M. D., Howieson, D. B., Bigler, E. D., & Tranel, D. Neuropsychological assessment (5th ed.). (Oxford University Press, 2012).

- 36.Bechara, A., Damasio, A. R., Damasio, H. & Anderson, S. W. Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex. Cognition50, 7–15 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Bechara A, Tranel D, Damasio H. Characterization of the decision-making deficit of patients with ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 11):2189–202. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.11.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Derogatis, L. SCL-90-R. Cuestionario de 90 síntomas. [SCL-90-R. 90-Symptoms Questionnaire]. Baltimore MD: Clinical Psychometric Research (1994).

- 39.Derogatis, L. SCL-90-R. Cuestionariode 90 Síntomas-Manual. Madrid: TEA Ediciones (2002).

- 40.Garner, D. M. Eating Disorder Inventory-2. (Psychological Assessment Resources, 1991).

- 41.Garner, D. M. Inventario de Trastornos de la Conducta Alimentaria (EDI-2)-Manual. Madrid: TEA Ediciones (1998).

- 42.Kelley K, Preacher KJ. On effect size. Psychol. Methods. 2012;17:137–152. doi: 10.1037/a0028086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosnow RL, Rosenthal R. Computing contrasts, effect sizes, and counternulls on other people’s published data: General procedures for research consumers. Psychol. Methods. 1996;1:331–340. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.4.331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Finner H. On a Monotonicity Problem in Step-Down Multiple Test Procedures. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1993;88:920. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1993.10476358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Piccoli L, et al. Role of orexin-1 receptor mechanisms on compulsive food consumption in a model of binge eating in female rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1999–2011. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Latifi B, Adamantidis A, Bassetti C, Schmidt MH. Sleep-wake cycling and energy conservation: Role of hypocretin and the lateral hypothalamus in dynamic state-dependent resource optimization. Frontiers in Neurology. 2018;9:790. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feng P, Vurbic D, Wu Z, Hu Y, Strohl KP. Changes in brain orexin levels in a rat model of depression induced by neonatal administration of clomipramine. J. Psychopharmacol. 2008;22:784–791. doi: 10.1177/0269881106082899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boersma GJ, et al. Failure to upregulate Agrp and Orexin in response to activity based anorexia in weight loss vulnerable rats characterized by passive stress coping and prenatal stress experience. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;67:171–81. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Piantadosi PT, Holmes A, Roberts BM, Bailey AM. Orexin receptor activity in the basal forebrain alters performance on an olfactory discrimination task. Brain Res. 2015;1594:215–22. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chien Y-L, et al. Elevated plasma orexin A levels in a subgroup of patients with schizophrenia associated with fewer negative and disorganized symptoms. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;53:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fagundo AB, et al. Executive Functions Profile in Extreme Eating/Weight Conditions: From Anorexia Nervosa to Obesity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43382. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weinbach N, Bohon C, Lock J. Set-shifting in adolescents with weight-restored anorexia nervosa and their unaffected family members. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2019;112:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Calva, C. B. & Fadel, J. R. Intranasal administration of orexin peptides: Mechanisms and therapeutic potential for age-related cognitive dysfunction. Brain Res, 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.08.024 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Abdel-Magid AF. Antagonists of Orexin Receptors as Potential Treatment of Sleep Disorders, Obesity, Eating Disorders, and Other Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;7:876–877. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fadel JR, Jolivalt CG, Reagan LP. Food for thought: The role of appetitive peptides in age-related cognitive decline. Ageing Research Reviews. 2013;12:764–776. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kastin AJ, Akerstrom V. Orexin A but not orexin B rapidly enters brain from blood by simple diffusion. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;289:219–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nobunaga M, et al. High fat diet induces specific pathological changes in hypothalamic orexin neurons in mice. Neurochem. Int. 2014;78:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arihara Z, et al. Immunoreactive orexin-A in human plasma. Peptides. 2001;22:139–142. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(00)00369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]