Abstract

Background:

The execution of resistance exercise against heavy loads promotes an acute intraocular pressure (IOP) rise, which has detrimental effects on ocular health. However, the effect of load on the IOP behavior during exercise remains unknown due to technical limitations.

Hypotheses:

IOP monitoring during isometric squat exercise permits assessment of IOP behavior during physical effort. Second, greater loads will induce a higher IOP rise.

Study Design:

Randomized cross-sectional study.

Level of Evidence:

Level 2.

Methods:

Twenty-six young adults (13 women, 13 men) performed an isometric squat exercise against 3 loads relative to their maximum capacity (low, medium, and high). IOP was measured before, during (1 measurement every 6 seconds), and after exercise (10 seconds of recovery).

Results:

There was a progressive IOP rise during exercise, which was dependent on the load applied (Bayes factor10 >100). Higher IOP values were found in the high load condition in comparison with the medium (mean IOP difference = 1.5 mm Hg) and low (mean IOP difference = 3.1 mm Hg) conditions, as well as when the medium load was compared with the low load condition (mean IOP difference = 1.6 mm Hg). Men reached higher IOP values in comparison with women during the last measurements in the high load condition. Ten seconds of recovery were enough to obtain IOP values similar to baseline levels.

Conclusion:

Isometric squat exercise induces an immediate and cumulative IOP elevation, which is positively associated with the load applied. These IOP increments return to baseline values after 10 seconds of recovery, and men demonstrate a more accentuated IOP rise in comparison with women when high levels of effort are accumulated.

Clinical Relevance:

These findings may help in better management of different ocular conditions and highlight the importance of an individualized exercise prescription in clinical populations.

Keywords: ocular health, eye care, glaucoma management, rebound tonometry, exercise prescription

It is well known that performing physical exercise on a regular basis promotes a number of beneficial physiological adaptations, which are highly dependent on the type of exercise and participants’ characteristics.11 In the field of ophthalmology and optometry, the influence of physical effort on the ocular physiology has been investigated because of its potentially beneficial or harmful effects on eye health.36 One of the ocular indices that has received significant research attention is intraocular pressure (IOP), since it is the only proven modifiable risk factor in the management of glaucoma.1 Managing glaucoma is of critical importance as it is one of the leading causes of irreversible blindness worldwide, and projections of glaucoma prevalence estimate that 76 million people will suffer from glaucoma in 2020.27 Therefore, identifying the most pertinent interventions, including physical exercise to properly manage glaucoma, are of great importance.37

Several factors are known to influence the IOP response to physical exercise, such as the type of physical exercise, participants’ fitness level, and exercise intensity, among others.32,36,37 Within these factors, the type of physical exercise is probably the factor that has received the most research attention. The majority of studies conclude that low-intensity aerobic exercise or endurance exercise performed against low relative loads reduce IOP in both the short and long term when IOP is assessed after exercise,20,29 whereas the execution of strength exercise with high relative loads is associated with an acute IOP increase.26,28,30,32,33 Taken together, these studies recommend avoiding the execution of strength exercises against heavy loads, especially in glaucoma patients or those at risk, and thus, an individualized exercise prescription is recommended for the appropriate management of ocular health.

Because of methodological limitations, IOP behavior while performing strength exercises remains largely unknown. Regarding strength exercises, the majority of studies have used a pre/post design (ie, IOP was assessed before and after exercise).26,28,33 However, since there is evidence that IOP values change quickly once the strength exercise has ceased,20,25,28 it is essential to continuously assess IOP behavior while performing strength exercises. Notably, isometric exercises where athletes maintained the same body position during the entire set allowed exploration of IOP variations during different modalities of this exercise.2,4 For example, Bakke et al2 investigated IOP variations by employing an electronic continuous-indentation tonometer while participants executed a 2-minute handgrip isometric exercise (40% maximal voluntary contraction of the forearm), whereas Castejon et al4 explored IOP behavior with a Goldman tonometer every 30 seconds during a 2-minute handgrip (30% of maximal voluntary contraction) and squat (knees flexed at 90° without any additional load) isometric exercises. These investigations provide evidence that isometric exercises induce a progressive IOP rise, in particular higher increments in the squat exercise compared with the handgrip exercise. Nevertheless, no study has continuously determined IOP behavior during the execution of isometric exercises performed against different loading magnitudes, as it has been carried out with dynamic strength exercises in a pre/post design.28,32 We consider it of interest to semicontinuously assess the impact of isometric exercise intensity on the IOP variations during isometric squat exercise against different loads.

To address this research caveat in related literature, the main objectives of the present study were (1) to evaluate IOP behavior during a 1-minute isometric squat exercise with semicontinuous IOP assessment and (2) to determine the impact of the load applied on IOP measurements. Complementarily, (3) we tested possible differences in IOP changes between men and women. We hypothesized that (1) IOP measurements would progressively increase during a 1-minute exercise period2,4 and (2) a significant IOP rise would be induced while executing strength efforts; a greater IOP rise was expected for higher relative loads, as shown with dynamic strength exercises.28 Finally, due to the lack of similar studies together with previous findings reporting that the between-sex differences in the physiological responses to isometric exercise are dependent on the variable assessed,16,35 (3) the null hypothesis was that no differences in IOP variations would be observed between men and women.

Methods

Participants

An a priori power analysis to determine the sample size, assuming an effect size of 0.20, alpha of 0.05, and power of 0.90, predicted a required sample size of 24 participants (12 per group) using mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA). At this point, 26 physically active university students recruited from the Faculty of Sport Sciences at the University of Granada took part in this study (13 men, age [mean ± SD] 23.4 ± 2.8 years and 13 women, age 22.1 ± 2.5 years). All of them were involved in approximately 8 physical activity classes per week, but none of them was an active athlete. Participants were free of any physical limitation that could compromise testing performance and had no history of any ocular or cardiovascular disease or surgery. Participants were instructed to avoid any strenuous exercise 2 days prior to each testing session. All participants had 2 or more years of experience in strength training, which was considered an inclusion criterion. Participants were first informed of the procedures involved and then signed a written informed consent form prior to initiating the study. The study protocol adhered to The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association and was approved by the institutional review board.

Experimental Design and Procedure

A mixed design was used to evaluate the influence of isometric squat exercise performed against different loads on IOP values in men and women. IOP measurements were taken before and after the exercise as well as during the 1-minute isometric exercise by semicontinuous IOP assessment. The within-participants factors were the load (low, medium, high) and the point of measure (before exercise, during exercise [points: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10], and recovery), and the sex (men and women) was the between-participants factor. IOP was the dependent variable.

Participants came into the laboratory on only 1 occasion. When they arrived, they read and signed the consent form and filled in the demographic questionnaire. Then, participants were instructed to warm up, and we described how to execute the isometric squat exercise correctly. At this point, an experienced strength and conditioning researcher individually determined the heaviest load that each participant could hold for 1 minute during the isometric squat exercise performed at a knee angle of 90°. Participants performed the exercise against a submaximal load and were told to stop after 20 seconds when they or the researcher believed that the load was too light. The load was then increased in agreement between the participant and the researcher until the participants performed a 1-minute effort and the participant and the researcher determined that it was a maximal effort. A maximum of 3 attempts were needed to determine the heaviest load. After this, participants rested for 10 minutes before the beginning of the first experimental condition. Participants randomly performed the isometric squat exercise against 3 different loads that were separated by 10 minutes. First, we conducted a baseline measure of IOP, and then participants adopted the squatting position while holding the corresponding load, and an experienced optometrist measured the IOP during the 1-minute period (see detailed exercise description below). When the isometric squat exercise ended, another IOP measurement was obtained after 10 seconds of passive recovery in standing position.

Squat Isometric Exercise

Participants performed the isometric squat exercise with their feet approximately shoulder-width apart and at a knee angle of 90°. Participants were instructed to hold the static position at 90° of knee flexion for 1 minute against 3 different loads, which were applied in a randomized order. The minimum loading condition represented the participant’s own body mass (ie, no external load was applied). The maximum loading condition represented the heaviest load with which the participants could hold the isometric squat position for 1 minute (45.9 ± 6.5 kg in men and 30.1 ± 5.1 kg in women). The medium loading condition represented half of the maximum load (26.2 ± 3.3 kg in men and 18.2 ± 2.2 kg in women). The external load for the medium and maximum loading conditions was applied by means of the barbell of a Smith machine (Technogym) positioned across the top of the shoulders and upper back. A rest period of 10 minutes was imposed between successive sets. Participants were instructed to maintain a proper inhalation and exhalation pattern during the exercise. Specifically, they were instructed to avoid the Valsalva maneuver, which has showed to increase IOP during maximal exertion, in absence of other factors.3

IOP Assessment

A rebound tonometer was used to assess IOP (Icare, TiolatOy, Inc), which has been previously clinically validated21 and employed in related research.26,31 This apparatus presents some advantages in comparison with other techniques (eg, Goldman applanation tonometry): (1) it is portable and handheld, (2) it can rapidly measure IOP, (3) the procedure is well tolerated, and (4) measuring does not require the use of topical anesthesia.21 The inherent characteristics of the tonometer and the exercise (static exercise with neutral neck position) allowed us to semicontinuously measure IOP. This constitutes the main novelty of this study in comparison with previous investigations, where the effects of different types of strength or endurance exercises were tested in a simple pre/post design.26,28,31-33 While exercising, participants were instructed to fixate on a distant target as consecutive measurements were taken against the central cornea. Every 6 measurements, the mean value is displayed, and the examiner vocalized the IOP value to a research assistant for data logging. During the 1-minute isometric exercise, the examiner acquired IOP values in a continuous fashion. Because of (1) the tonometer’s inability to acquire IOP measurements at exact time intervals, (2) the lack of exact time stamps for the measurements, and (3) the manual logging of the values, we describe a process to overcome these technical restrictions and obtain a set of equally distributed values at regular intervals with exact time stamps in the Data Processing subsection. In addition, a baseline IOP was measured before each exercise, and a recovery measurement was obtained 10 seconds after the exercise. All measurements were taken in the right eye.

Data Processing

We developed a procedure to obtain a set of equally distributed IOP measurements at regular intervals, thus overcoming the timestamping and lack of automatic logging restrictions of the rebound tonometer, described in the previous section. We based our method on multirate digital signal processing, in particular sample-rate conversion, which is the process of changing the sampling rate of a discrete sampled signal to obtain a new discrete representation of the underlying continuous signal, in this case the IOP signal.9 IOP is a continuous function, as when IOP values rise and fall between 2 pressures, IOP will always take all intermediate values between those 2 pressures. In our process, we treated the obtained samples as geometric points and created the necessary new points by polynomially interpolating those values, essentially approximating the source, continuous IOP signal, and then resampling at 10 discrete intervals for the 1-minute period, that is, every 6 seconds.

Simply stated, when measuring IOP using the rebound tonometer, we essentially sampled the continuous IOP function at slightly irregular intervals. The obtained values were the values of the IOP function at those moments in time. But because the function was continuous, we were able to reconstruct the IOP function from the sample measurements and then resample the function at specific, regular intervals, thus obtaining a fixed set of values at these exact intervals. The new data points were estimated within the range of the discrete set of sampled data points.

Statistical Analysis

We used a Bayesian approach to test the influence of isometric squat exercise performed against different external loads on IOP. This method of statistical inference presents numerous advantages in comparison with classical “frequentist” approaches.19,34 The interpretation of the Bayes factor (BF) enables the quantification of the evidence for one hypothesis relative to another (alternative vs null hypotheses), allowing us to determine whether nonsignificant results confirm the null hypothesis, or whether data are just not sensitive enough to accept any hypotheses. Based on the evidence categories for BF10 (alternative against null hypotheses) proposed by Jeffreys,14 a BF10 higher than 3 reveals substantial evidence for the alternative hypothesis, whereas a BF10 less than 1/3 determinates substantial evidence for the null hypothesis. However, a BF10 between 1/3 and 3 is considered nonsensitive for accepting any hypothesis (see table 1 of Wetzels et al34 for a detailed description of BF categories).

First, in order to test hypothesis 1, we used a mixed Bayesian ANOVA to evaluate the cumulative effect of a 1-minute isometric squat exercise on IOP, with the load (low, medium, high) and the point of measure (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10) as the within-participants factors, and with sex (men and women) as the between-participants factor. Complementarily, we calculated 3 separate linear regression analyses to assess the IOP behavior during the 1-minute isometric effort against each load. To examine the acute impact of the load on IOP (objective 2), we conducted a repeated-measures Bayesian ANOVA with the load (low, medium, high) and the point of measure (before exercise, during effort [average IOP value from the 10 measurements taken during the 1-minute exercise], and after 10 seconds of passive recovery) as the within-participants factor. We also reported Cohen effect sizes (ES), as they can provide additional evidence of how much the results deviate from the null hypothesis, and they were interpreted as negligible (<0.2), small (0.2-0.5), moderate (0.5-0.8), and large (≥0.8).7 The JASP statistics package (version 0.9) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Aiming to ensure that there were no differences from the baseline IOP values before any of the 3 exercises, we performed a 1-way Bayesian ANOVA with the load (low, medium, high) as the only within-participants factor. We found that there was substantial evidence for the null hypothesis when the 3 IOP measurements before effort were analyzed (BF10 = 0.203), and thus, the baseline IOP values between exercises were similar.

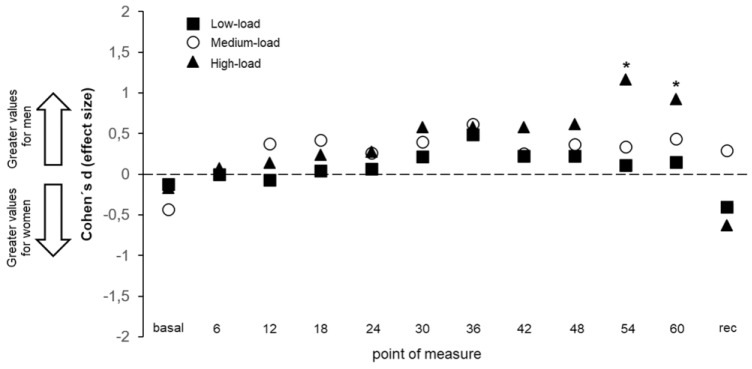

The first set of analyses to assess IOP behavior during the 1-minute isometric squat exercise (objective 1) revealed decisive evidence for the alternative hypothesis for the load, the point of measure, and the interaction load × point of measure (BF10 > 100 in the 3 cases). This means that significant differences (acceptance of the alternative hypothesis) were found for these factors. Post hoc comparisons for the different loads demonstrated substantial evidence for the alternative hypothesis between the low and high loads (BF10 > 100, ES = 1.41), the low and medium loads (BF10 > 100, ES = 0.67), and between the medium and high loads (BF10 > 100, ES = 0.63). This means that higher IOP values were obtained when the isometric effort was performed against greater loads. The IOP behavior during the 1-minute isometric squat exercise showed a linear increase over time, with a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.91 for the low load, 0.90 for the medium load, and 0.95 for the high load (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of performing 1-minute isometric squat exercise against 3 different loads on intraocular pressure. The recovery value was taken 10 seconds after exercise, and the gray area represents the 1-minute isometric physical effort. Error bars show the SE. All values are calculated across participants (n = 26). Rec = recovery.

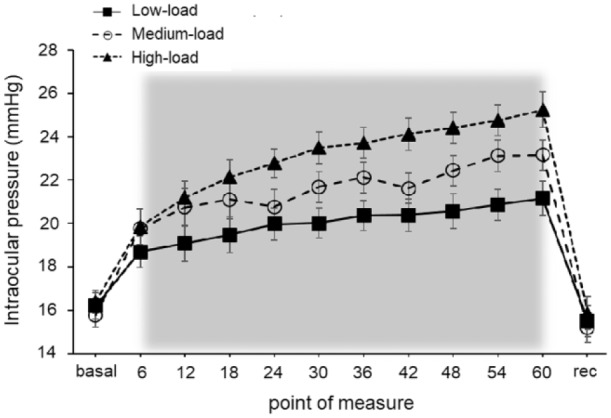

Second, we analyzed the impact of the load applied on IOP variations (objective 2); the load factor showed substantial evidence for the null hypothesis (BF10 = 0.288), whereas decisive evidence for the alternative hypothesis was found for the point of measure and the interaction load × point of measure (BF10 > 100 in both cases). This means that IOP values were considerably different between the 3 points of measure (baseline, during effort, and during recovery), although the load did not have a significant impact on IOP behavior in this case. Post hoc comparisons for the different loads demonstrated substantial evidence for the alternative hypothesis between the low and high loads (BF10 = 9.403, ES = 0.51), whereas the comparison between the medium and high loads provided anecdotal evidence for the alternative hypothesis (BF10 = 2.062, ES = 0.37); and last, when the low and medium loads were compared, we found substantial evidence for the null hypothesis (BF10 = 0.167, ES = 0.12). Regarding the point of measure, there was decisive evidence for the alternative hypothesis in the comparison of the IOP value obtained before effort and the average value from those taken during isometric effort (BF10 > 100, ES = 2.24). Similarly, decisive evidence for the alternative hypothesis was found when the average IOP obtained during effort was compared with the recovery IOP measurement (BF10 > 100, ES = 2.12). Hence, higher IOP values were found for the high load in comparison with the low load, as well as when the IOP values obtained during effort were compared with those taken before effort and during recovery. However, substantial evidence for the null hypothesis was revealed for the comparison between the baseline and recovery IOP values (BF10 = 0.32, ES = 0.24) (Figure 2), suggesting that baseline and recovery IOP values were comparable.

Figure 2.

Effects of performing 1-minute isometric squat exercise against 3 different loads on intraocular pressure (IOP). The effort value depicts the average IOP from the 10 IOP measurements taken during exercise. # and * indicate statistically significant differences between the different points of measure and loads, respectively (corrected P value <0.05). Error bars show the standard error. All values are calculated across participants (n = 26).

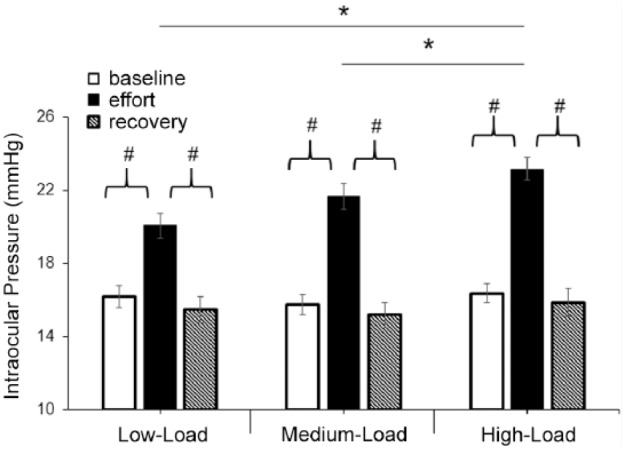

Regarding sex (objective 3), our data were not sensitive enough for the main effect of sex (BF10 = 0.586), whereas the interactions sex × load and sex × point of measure demonstrated substantial evidence to accept the alternative hypothesis (BF10 > 100 in both cases). Figure 3 displays all the post hoc comparisons carried out for all the points of measure and loads, demonstrating that men reached higher IOP values in comparison with women during the last measurements conducted with the high-load condition.

Figure 3.

Standardized differences (Cohen d effect size) in the intraocular pressure changes between men and women when performing the isometric squat exercise against 3 different loads. All values are calculated across participants (n = 26). Rec = recovery.

Discussion

The main finding of the present study revealed that IOP linearly increases over time during a 1-minute isometric squat exercise. In addition, the application of higher loads was also associated with larger IOP increments, while trivial differences in IOP behavior were observed between men and women. These results are in line with previous studies that showed an IOP rise during isometric exercises2,4; however, the present study shows that load is an important modulator of IOP behavior during isometric effort. Relevantly, although IOP measurements were meaningfully incremented at the end of the 1-minute effort (by 4-8 mm Hg), IOP returned to baseline levels after only 10 seconds of recovery, which evidences the transient nature of IOP changes caused by physical effort once the effort has ceased. Taken together, these findings highlight that isometric strength exercises, especially when performed against heavy loads, should be avoided when low and stable IOP values are desirable. These findings may have important implications not only for glaucoma patients but also for the management of other ocular conditions such as myopic fundus pathology or keratoconus where abrupt IOP elevations may provoke stretching of the fundus or cone progression, respectively.18

Regardless of the load imposed, our data indicate that the time under tension provokes a strong linear IOP rise (R2 = 0.90-0.95). This linear tendency of IOP values to increase over time agrees with recent evidence on the influence of the accumulated level of effort during resistance training on the structural and neuromuscular adaptations induced by the progressive accumulation of fatigue.22 Similar results have been published by Bakke et al,2 who found a linear IOP increase during the handgrip isometric exercise while participants exerted 40% of the maximal voluntary isometric force; or Castejon et al,4 who also showed a linear IOP rise, as measured every 30 seconds during a 2-minute period, while the participants adopted the squatting position without the application of any additional load. Here, we found that the accumulated effect of isometric exercise on IOP is independent of the exercise intensity, and interestingly, the semicontinuous IOP assessment of our study indicates that these effects are essentially instantaneous.

The main novelty of the present investigation is that the magnitude of the load applied during the isometric squat exercise significantly influenced IOP variations, that is, IOP values further increased under higher loading conditions. The average IOP increment during the 1-minute isometric squat exercise was 24% for the low load, 37% for the medium load, and 41% for the high load, whereas after 1 minute of exercise (ie, last point of measure during effort) the IOP was incremented by 36%, 52%, and 59% for the low, medium, and high loads, respectively. These findings present preliminary evidence with respect to the role of intensity when performing isometric exercises, which are of special relevance since external loads are commonly applied during isometric training.17 Our data converge with the results found for blood pressure, which have shown that blood pressure increases as a consequence of executing isometric exercises in an intensity-dependent manner.12 In line with these results, during dynamic strength exercises IOP measurements were positively and linearly correlated with the magnitude of the load applied.28,31 Nevertheless, the IOP rises obtained in this study were substantially higher than those found when performing dynamic strength exercises. Based on the present outcomes, it is reasonable to recommend abstaining from isometric exercise when maintaining stable IOP levels is desired or necessary, since a higher short-term IOP fluctuation (within a daily IOP curve) has been identified as a considerable risk factor for glaucoma onset and progression.8,10

We only found a significant difference in IOP measurements between men and women when the high load was applied, with women showing a more stable IOP behavior during the last 2 measurements (Figure 3). This result is preliminary, since to the best of our knowledge, no previous study has compared IOP variations during isometric exercise between men and women. These results are in line with accumulated evidence of sex-related differences in cardiovascular and autonomic regulation,23 with women exhibiting lower reactivity in comparison with men. In this regard, Wong et al35 found a smaller cardiovascular response to isometric exercise in women related to their greater suppression of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex activity, which has been linked with sympathetic control of the cardiovascular system. Hence, a similar mechanism to the lower physiological reactivity and stronger sympathetic control of the cardiovascular system in women may explain the reduced IOP reactivity observed in women in this study.

Our results revealed that IOP values returned to baseline levels after 10 seconds of passive recovery in all the tested conditions. This finding corroborates that IOP changes induced by isometric exercise are very transient,2 which, consequently, has 2 important implications: (1) the side effects of isometric exercise on the ocular health may only occur during physical effort, and therefore (2) the assessment of IOP variations to different exercises in a pre/post design should be cautiously interpreted, since the post measurements may not reflect the actual IOP variation induced by the corresponding exercise.

There are some factors that may limit the generalizability of the findings observed in this pilot study. The current findings should be cautiously interpreted because of our relatively small sample size, along with the novelty of our experimental design and data processing. Further studies with larger sample sizes should be performed to explore the generalizability of the results found in this pilot study. First, the present results are of special interest for the management of different ocular conditions; however, our experimental sample was formed by young, healthy individuals. The inclusion of glaucoma patients, who demonstrably have an altered autoregulatory control of the ocular hemodynamics and aqueous humor dynamics and suffer higher IOP fluctuations to a variety of stress tests,6 is warranted in future studies. Of note, De Moraes et al10 recently showed that even these transient IOP spikes during the day (when measured with a contact lens sensor) have a detrimental effect on the visual fields of glaucoma patients. Second, previous investigations have stated that fitness level is an important modulator of the IOP response to dynamic strength exercise,32 with trained individuals showing a smaller IOP change than untrained counterparts. Third, in our study, we continuously evaluated IOP behavior during a 1-minute isometric squat exercise, obtaining an abrupt IOP rise, but it is desirable to continuously monitor IOP behavior after exercise as well, in order to test IOP recovery after isometric exercise. Fourth, the execution of the Valsalva maneuver provokes IOP fluctuation,3 and although participants were asked to avoid it, we cannot rule out that they did it unintentionally. It would be of special interest to assess the role of the breathing pattern during isometric exercise on the IOP behavior. Fifth, postural changes are known to alter the ocular hemodynamics.13,24 Here, all exercises were performed in standing position, and thus, we consider it of interest to study the possible influence of adopting different head and body positions on the eye physiology while performing isometric exercises (eg, abdominal planks). Sixth, ocular physiology is known to be dependent on age and ethnicity.5 Continuous technological advancements in ocular imaging techniques (eg, optical coherence tomography angiography or anterior segment optical coherence tomography) may be incorporated into this line of research to further deepen our understanding of ocular physiological responses (eg, optic nerve integrity and function, retinal oxygenation, aqueous humor drainage) caused by exercise, aiming to develop the recommendations for exercise prescription in patients with different ocular conditions.15

In summary, isometric squat exercise provokes a rapid and progressive IOP elevation, and these IOP variations are positively associated with the magnitude of the external load applied during exercise. IOP drops shortly after ceasing the physical effort (10 seconds of recovery), and men exhibited a more accentuated IOP rise at the end of the exercise compared with women. These findings may contribute to establish the most appropriate guidelines for exercise prescription in terms of ocular health, particularly relevant for glaucoma patients or those at high risk of glaucoma. Based on the current findings, we recommend abstaining from isometric squat exercise, particularly under heavy loading conditions, when stable IOP levels are desirable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants who selflessly collaborated in this research.

Footnotes

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest in the development and publication of this article.

References

- 1. AGIS Investigators. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7. the relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;130:429-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bakke EF, Hisdal J, Semb SO. Intraocular pressure increases in parallel with systemic blood pressure during isometric exercise. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:760-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brody S, Erb C, Veit R, Rau H. Intraocular pressure changes: the influence of psychological stress and the Valsalva maneuver. Biol Psychol. 1999;51:43-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Castejon H, Chiquet C, Savy O, et al. Effect of acute increase in blood pressure on intraocular pressure in pigs and humans. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1599-1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chan MPY, Grossi CM, Khawaja AP, et al. Associations with intraocular pressure in a large cohort. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:771-782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clement C, Goldberg I. Water drinking test: new applications. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;44:87-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coleman AL, Miglior S. Risk factors for glaucoma onset and progression. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53:3-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crochiere RE, Rabiner LR. Multirate Digital Signal Processing. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 10. De Moraes CG, Mansouri K, Liebmann JM, Ritch R; Triggerfish Consortium. Association between 24-hour intraocular pressure monitored with contact lens sensor and visual field progression in older adults with glaucoma. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136:779-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1334-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greaney JL, Wenner MM, Farquhar WB. Exaggerated increases in blood pressure during isometric muscle contraction in hypertension: role for purinergic receptors. Auton Neurosci Basic Clin. 2015;188:51-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jasien JV, Jonas JB, Gustavo De, Moraes C, Ritch R. Intraocular pressure rise in subjects with and without glaucoma during four common yoga positions. PLoS One. 2015;10:1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jeffreys H. Theory of Probability. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jia Y, Bailey ST, Hwang TS, et al. Quantitative optical coherence tomography angiography of vascular abnormalities in the living human eye. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:e2395-e2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kent-Braun JA, Ng AV, Doyle JW, Towse TF. Human skeletal muscle responses vary with age and gender during fatigue due to incremental isometric exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:1813-1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kisner C, Colby LA, Borstad J. Therapeutic Exercise: Foundations and Techniques. Philadephia, PA: FA Davis; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18. McMonnies CW. Intraocular pressure and glaucoma: is physical exercise beneficial or a risk? J Optom. 2016;9:139-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mulder J, Wagenmakers EJ. Editors’ introduction to the special issue “Bayes factors for testing hypotheses in psychological research: Practical relevance and new developments,” J Math Psychol. 2016;72:1-5. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Najmanova E, Pluhacek F, Botek M. Intraocular pressure response to moderate exercise during 30-min recovery. Optom Vis Sci. 2016;93:281-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pakrou N, Gray T, Mills R, Landers J, Craig J. Clinical comparison of the Icare tonometer and Goldmann applanation tonometry. J Glaucoma. 200;17:43-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pareja-Blanco F, Rodríguez-Rosell D, Sánchez-Medina L, et al. Effects of velocity loss during resistance training on athletic performance, strength gains and muscle adaptations. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017;27:724-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Parker BA, Kalasky MJ, Proctor DN. Evidence for sex differences in cardiovascular aging and adaptive responses to physical activity. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;110:235-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Prata TS, De Moraes CGV, Kanadani FN, Ritch R, Paranhos A. Posture-induced intraocular pressure changes: considerations regarding body position in glaucoma patients. Surv Ophthalmol. 2010;55:445-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Price E, Gray L, Humphries L, Zweig C, Button N. The effect of exercise on intraocular pressure and pulsatile ocular blood flow in healthy young adults. Optom Vis Sci. 2003;87:1363-1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rüfer F, Schiller J, Klettner A, Lanzl I, Roider J, Weisser B. Comparison of the influence of aerobic and resistance exercise of the upper and lower limb on intraocular pressure. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014;92:249-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng CY. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:2081-2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vera J, Garcia-Ramos A, Jiménez R, Cárdenas D. The acute effect of strength exercises at different intensities on intraocular pressure. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2017;255:2211-2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vera J, Garcia-Ramos A, Redondo B, Cárdenas D, De Moraes CG, Jiménez R. Effect of a short-term cycle ergometer sprint training against heavy and light resistances on intraocular pressure responses. J Glaucoma. 2018;27:315-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vera J, Jiménez R, Garcia-Ramos A, Cárdenas D. Muscular strength is associated with higher intraocular pressure in physically active males. Optom Vis Sci. 2018;95:143-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vera J, Jiménez R, Redondo B, Cárdenas D, De Moraes CG, Garcia-Ramos A. Intraocular pressure responses to maximal cycling sprints against different resistances: the influence of fitness level. J Glaucoma. 2017;26:881-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vera J, Jiménez R, Redondo B, Cárdenas D, García-Ramos A. Fitness level modulates intraocular pressure responses to strength exercises. Curr Eye Res. 2018;43:740-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vieira G, Oliveira H, de Andrade D, Bottaro M, Ritch R. Intraocular pressure during weight lifting. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1251-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wetzels R, Matzke D, Lee MD, Rouder JN, Iverson GJ, Wagenmakers EJ. Statistical evidence in experimental psychology: an empirical comparison using 855 t tests. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6:291-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wong SW, Kimmerly DS, Masse N, Menon RS, Cechetto DF, Shoemaker JK. Sex differences in forebrain and cardiovagal responses at the onset of isometric handgrip exercise: a retrospective fMRI study. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:1402-1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wylegala A. The effects of physical exercises on ocular physiology: a review. J Glaucoma. 2016;25:e843-e849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhu MM, Lai JSM, Choy BNK, et al. Physical exercise and glaucoma: a review on the roles of physical exercise on intraocular pressure control, ocular blood flow regulation, neuroprotection and glaucoma-related mental health. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018;96:e676-e691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]