Abstract

Objectives

Doctors increasingly experience high levels of burnout and loss of engagement. To address this, there is a need to better understand doctors’ work situation. This study explores how doctors experience the interactions among professional fulfilment, organisational factors and quality of patient care.

Design

An exploratory qualitative study design with semistructured individual interviews was chosen. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed by a transdisciplinary research group.

Setting

The study focused on a surgical department of a mid-sized hospital in Norway.

Participants

Seven doctors were interviewed. A purposeful sampling was used with gender and seniority as selection criteria. Three senior doctors (two female, one male) and four in training (three male, one female) were interviewed.

Results

We found that in order to provide quality care to the patients, individual doctors described ‘stretching themselves’, that is, handling the tensions between quantity and quality, to overcome organisational shortcomings. Experiencing a workplace emphasis on production numbers and budget concerns led to feelings of estrangement among the doctors. Participants reported a shift from serving as trustworthy, autonomous professionals to becoming production workers, where professional identity was threatened. They felt less aligned with workplace values, in addition to experiencing limited management recognition for quality of patient care. Management initiatives to include doctors in development of organisational policies, processes and systems were sparse.

Conclusion

The interviewed doctors described their struggle to balance the inherent tension among professional fulfilment, organisational factors and quality of patient care in their everyday work. They communicated how ‘stretching themselves’, to overcome organisational shortcomings, is no longer a feasible strategy without compromising both professional fulfilment and quality of patient care. Managers need to ensure that doctors are involved when developing organisational policies, processes and systems. This is likely to be beneficial for both professional fulfilment and quality of patient care.

Keywords: ethics (see medical ethics), preventive medicine, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

In this exploratory study, given our priority to capture in-depth, nuanced aspects, individual doctor interviews were given priority over the potentially higher number of participants that could have been included in group interviews. The interdisciplinary research group, conducting the analytical work, further provides a methodological basis to find a rich interpretation towards an empirically grounded doctors’ voice.

This study has a potential limitation in that the empirical material was based on interviews with only seven doctors (this represented about 30% of the doctors working at the department). In order to capture input also from doctors not being interviewed, a feedback session was included, where the researchers presented tentative findings to the larger group of doctors at the department. Both those who participated in interviews and several doctors who had not been interviewed, confirmed the researchers understanding of the local work situation. This substantiates the findings.

Transferability of this study with a small sample of doctors from a hospital is not claimed; however, being consistent with previous research, our study findings can be useful to healthcare delivery organisations experiencing similar challenges in their specific context.

Introduction

High-quality healthcare depends on high-tech equipment, sufficient resources and reliable evidence and on health professionals who are engaged and find meaning with their work. Researchers have recently argued for expanding the traditional healthcare improvement goals. In addition to enhancing patient treatment, securing the population’s health and reducing the per capita cost of healthcare,1 they argue for promoting professional fulfilment.2–4 Bodenheimer and Sinsky5 expressed this succinctly as ‘care of the patient requires care of the provider’.

In order to improve quality of care, while containing costs, and promoting professional fulfilment, we seem to need additional knowledge. A review from 2013 found that 70% of interventions aiming to improve quality and reduce healthcare costs did not succeed in doing both.6 Common strategies were hospital or department mergers and downsizing, without attaining increased quality7 and leading to negative effects for work environment as well as increased stress, burnout and feelings of alienation among employees.8–10

Several studies have explored the links between professional fulfilment and different measures of quality of care (both as perceived by doctors themselves or more objectively measured in relation to treatment outcomes or patient complaints).11–15 Other studies have explored the relationships between different organisational factors and how they influence professional behaviour, motivation, engagement and satisfaction.16–22 Only few studies have studied the dynamic interaction among all three dimensions: organisational factors, quality of patient care and professional fulfilment.23–25 Although these studies indicate the importance of doctors’ active involvement in change processes, research informs us that such engagement is limited.26–29 We need to understand more about these relationships. To better care for the providers, a better understanding of the interactions among professional fulfilment, quality of patient care and organisational factors is needed.30 There seems to be a call for research to provide more practice-informed and actionable knowledge to facilitate local workplace development.30 31

In Norway, as in other countries, recent decades have seen a stronger emphasis on budget control and value for money. A number of reforms are implemented, all with the intention to improve quality, reduce waste and lead to better priorities. The many reforms and increased focus on budget constraints seem to have led to some scepticism among doctors.32 Norwegian doctors have expressed their worries about maintaining the quality of care through the many reforms and changes.33

The Norwegian healthcare system is a single payer, universal coverage system, funded by the State. Hospital care is organised as regional trusts with independent boards. Yearly contracts are made with the Ministry of Health. Primary care is organised with independent contractors to the healthcare system. General practitioners (GPs) are gatekeepers to specialist care, and patients need to first meet with a GP before having access to specialist care. Patients incur a nominal copayment when receiving care services and the bulk of the funding comes from the State. Although doctors in Norway34 (as in other Western countries35) have high scores on work satisfaction, there is a clear difference between specialties. Community doctors and GPs scored highest and doctors in surgical disciplines scored lowest.36 Qualitative interviews of hospital doctors have found that surgeons, as one of three specialties, experience conflicts between adhering to their views of what a good doctor is/does and the consequences this has for the interaction with healthcare leaders, their colleagues and for the balance between work and home.37 In 2008, more than 30% of senior and 18% of junior hospital doctors reported working under ‘unacceptably’ high rates of stress fairly often or often and over 75% of hospital doctors reported fairly or very high stress related to frequent reorganisations.38

Thus, exploring how Norwegian doctors understand the relationships among organisational factors, professional fulfilment and quality of patient care will inform and support commensurate interventions towards improving doctors’ well-being and the quality of patient care.39

Aim

The study aims to explore how doctors experience the interactions among professional fulfilment, organisational factors and quality of patient care.

Methods

Design

An exploratory qualitative study design was chosen. Such a design is appropriate when there is limited knowledge.40 This study was conducted as the first part of a multiyear and multisite interactive41 42 research project, interviewing doctors from two hospitals in Norway and one in the USA. This article focuses on the first set of doctor interviews from one of the Norwegian hospitals.

Setting

The study was done in a mid-sized emergency hospital in Norway. The hospital provides medical, surgical and psychiatric care with approximately 1400 employees who serve a population of about 135 000. This is also a teaching hospital for doctors and nurses. The hospital has, during the last years, reorganised the executive leaders and engaged in a hospital-wide leadership development programme to create alignment with how new societal requirements are integrated and to facilitate improvements of managerial processes and processes impacting quality of patient care.

Following a presentation about the study to the hospital management, the researchers received approval to approach department managers. The study’s aim and interactive study concept were presented to the group of doctors and head of the department. Following an internal discussion, the surgical department agreed to participate. Both doctors and the leader of the surgical department expressed appreciation of the cooperative aspects of the study and the explicit intent to listen to doctors’ voices about their local situation.

Participants

The participating surgical department asked us to work with a small study population in order to minimise time conflict with doctors’ clinical work, without compromising the quality of the study. Based on experience from the research field and from interviewing doctors in other hospital settings, we agreed on a minimum number of seven doctors. This is about a third of all doctors at the department. For the most effective use of the limited resources, we used a purposeful sampling, which is a widely used technique for identification and selection of information-rich cases.40 Gender and seniority were used as selection criteria to provide maximum variation43 in the empirical material. Three participants were senior doctors (two female, one male) and four were in training (three male, one female).

Data collection

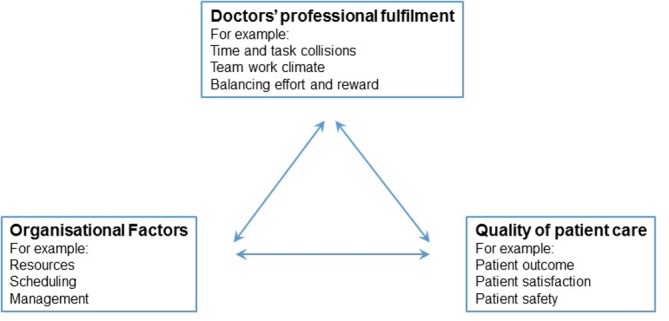

Data were collected via individual interviews. A semistructured interview guide was used to facilitate consistency between interviews.40 The questions were inspired by the quadruple aim5 and appreciative inquiry.44 The interview guide was initially developed by FB. It was then tested on KIR for readability and clarity. After adjustments and a new test with evaluation, it was accepted. All interviews were done in the local language. We constructed open-ended questions to allow the respondent to tell their own story.45 Each interview started with questions about number of years working as a doctor and the current position. Then the respondents were asked to describe a day when they felt satisfied or fulfilled at work and a day when they did not. After this, they were asked to reflect on the relationships among professional fulfilment, quality of patient care and organisational factors. To be consistent when introducing this question, the respondents were shown a conceptual model (figure 1). Each doctor received a written and oral description of the study before signing the written consent and before the interview started. An interview guide, translated into English, is available as online appendix 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework used in the interview situation.

bmjopen-2018-026971supp001.pdf (245.2KB, pdf)

The individual doctor interviews were conducted in November and December 2016. Interviews took place in a conference facility in the hospital area and were digitally recorded. Each interview was scheduled to last 60 min. The researchers allowed participants to use more time in order to provide information richness, given the limited numbers of interviews. This resulted in an average interview time of 74 min.

In order to capture rich information from this small number of participants,46 we were two experienced researchers with complementary experience participating in every interview but one. During the interview, one researcher was leading, while the other listened and took extensive notes, occasionally interacting to further probe interesting aspects relating to the study aim. Both researchers (PhD) had solid experience with physician interviews and knew the research field well. One interviewer (KIR) has a background as an occupational physician and many years of experience counselling doctors both individually and in groups. The other interviewer (FB) has a professional background as department head at a university hospital, working with organisational development for many years, educational background from industrial engineering and management and consultant level training in group relations theory.

Analysis

To provide for a multifaceted interpretation of the empirical material, the analytical process involved a team of four researchers with complimentary experiences. In addition to those two who conducted the interviews, a senior researcher (PhD) with experience in epidemiology and with professional background in surgical nursing took part (JR), as well as a senior healthcare researcher with a PhD in sociology (BB).

The analytical process started with a tentative analysis to capture the main content from the interviews. The two interviewers (FB+KIR) went through their notes and impressions from the interviews and started to create an overarching understanding. JR listened to all audio recordings and made notes with the targeted task to ask the material two key questions: what is the most pressing problem? and what do they do to handle/solve this problem? BB listened to most of the interviews and made notes about her first impressions. The research group then met and compared initial notes. This first step provided an overall perspective that was presented back to the department to allow them to react to it. This material provided good resonance with the participants and also with the other doctors who were present in the meeting but had not been interviewed. Also the head of the department confirmed that what the researcher presented back to the department was in line with his understanding.

The more developed analytical process was guided by Miles and Huberman47 and was done without specific analytical software. All interviews were transcribed verbatim in the local language. Based on the study aim, the interviews were read individually to capture words and sentences, meaning units, which showed similarities in terms of content. These meaning units were condensed and labelled with a descriptive code close to the textual meaning. Sometimes these codes were in English and sometimes they were in the local language. The research group met and each person presented their descriptive coding. Mostly there was congruence. When congruence was not experienced, face-to-face conversations were carried out to challenge each other’s perspective. Sometimes these conversations went back to the original text to find a common ground and interpretation before moving on. The researchers then worked to group the descriptive codes, and related meaning units, based on the ones having similar content. Each grouping received a tentative descriptive header. Once this was in place, two alternative routes of further sorting and abstraction were followed in a comprehensive analysis of the content. One was to use the conceptual framework from the interview (figure 1) and organise the different groupings in relation to if it concerned professional fulfilment, organisational factors or quality of patient care. This process created, at first, an experience of structure and cleanliness, but over time provided a blurred result, with a residual of empirical material that fitted in any or all of the three aspects. The other analytical route was to look for groupings that could be combined with only slightly broadening or altering the content, as symbolised by an adjustment of the descriptive header. This iterative process eventually contributed to form five empirical themes that integrated all interview material into a comprehensive understanding. Quotations are used in the result section to allow individual doctor voices to illustrate a central content.45

The interdisciplinary group of authors worked both individually and in a group to enrich the empirical interpretations and reduce the risk of any author overpowering the empirical material of doctors’ voices. During the analytical process we paid extra attention if we found data that did not fit with the other data, indicating there were some empirical nuances we were missing with our small sample of seven doctors. This did not happen, and regardless of gender or seniority, there was a high degree of commonality between the different doctor voices relating to the aim. During the analyses, it became clear that the seven information rich cases enabled a comprehensive understanding. It confirms, what Malterud et al 46 suggests, that a limited number of information rich interviews can contribute with new meaningful knowledge. During the analytical process alternative interpretations were continuously sought through critical reflections and ongoing conversations during face-to-face meetings. This process continued iteratively until alternative understandings and considerations were reconciled into a coherent result. Patton40 suggests that this type of research group triangulation is a way to reach comprehensive, robust and well-developed findings from a rich empirical material.

Ethics

This study followed the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki.48 The risk of harm to the participants was very low, and thus the project did not meet the criteria justifying a formal application to the ethics board, consistent with Norwegian law.49

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design or planning of the study.

Results

Analysing the interviewed doctors’ experiences about the interactions among professional fulfilment, organisational factors and quality of patient care resulted in an empirically grounded understanding with the following themes. (Quotes from participant are used to provide the original voice. Each doctor is assigned a random letter for anonymity.)

Quality of patient care crowded out by production numbers and economic data

Many doctors talked about how conversations at department meetings had changed. Previously, they were more about quality of clinical care, while now they mostly focused on the need to meet production targets and finding ways to handle budgetary constraints. The participant expressed how quality was starting to be experienced as an empty phrase, crowded out by production numbers and economic concerns.

Quality is more and more becoming an empty term in relation to what the hospital values are. What we hear about is mostly money issues and production numbers. (Doctor A)

Changes in workplace conversations, combined with an experience of limited recognition for good professional work, made some doctors express that they did not really ‘recognize the workplace’. Some of them also expressed concerns about who they were becoming in their role as doctors. One doctor experienced a change from being a trustworthy and autonomous professional to becoming more of a production worker.

I don’t feel that I come to work as a capable and autonomous resource anymore. I feel I come to work only to produce a certain number of procedures. (Doctor B)

While the interviewed doctors all appreciated swift and smooth operations, a new operating concept, with the explicit aim to increase output, troubled some. They expressed concerns about potential risks of patient complications since the allotted time was too limited to find anatomical landmarks and stop minor bleeding before proceeding to the next surgical step. With a dominating focus on quantity, there was an emergent worry as to whether individual quality standards were compromised.

Maybe the key dilemma is that you are pushed for quantity all the time. It leads you to start to feel, right after you go home from your on-call work, that you did not finish your task or finalize things the way you wanted to. You get pushed to increase quantity and it is affecting your own reference of good-quality work. (Doctor C)

The participants expressed unease about conversations focusing more on cost and production than quality, but at the same time, there was an awareness of the necessity of high productivity and cost control.

I am one of those doctors who consider that health care has an obligation to make sure we manage our resources and household with our tax-based money. (Doctor D)

‘Stretching oneself’ to deliver quality of patient care despite organisational shortcomings

The participants emphasised the importance of delivering good quality care, even if it meant ‘stretching themselves’ to overcome hindering organisational factors. The expression ‘stretching themselves’ is a descriptive term arising from the empirical analysis. It is used to capture the experience that an individual doctor had to find workarounds, which often involved overextending oneself, to balance the tension between production quantity versus quality and handling sudden resource shortages (‘due to illness you now also need to handle the ward in between doing your surgical cases’) and balancing the potential tension between work and home. This way of ensuring quality of patient care was considered common practice. However, several doctors had begun to wonder whether the individual workarounds could have negative consequences for the quality of patient care.

One starts to wonder if this constant stretching of oneself can have negative consequences. Like more patients expressing worries after their operations. (Doctor E)

One example of an organisational shortcoming concerned unforeseen variations in the daily operating schedule. This could result in long work hours for the doctors, impinging on the work–home balance. Another dimension of stretching relates to a so-called contract of conscience. This was not a formal contract but rather related to their professional identity as doctors. The ‘contract’ was driving them to further stretch themselves and spend considerable time at work on top of normal duties.

I have to be there until the operation is finished. I am really concerned whether I will be in time for kindergarten. It generates a lot of frustration, but I have an implicit contract with the patient and also to the hospital to make sure the operation is carried through. (Doctor E)

The accelerating struggle against time impacting well-being and quality of patient care

The struggle against time was a main concern in the interviews and the participants experienced that it influenced their overall well-being.

Suddenly you have one of these time and task collisions and it increases work strain and stress, impacting physical and mental health. You know, when you are expected to be in three places at once, it sort of triggers your stress level. (Doctor C)

The participants felt uncomfortable with an increasing number of time and task collisions and expressed concerns that this constant battle against time could jeopardise the quality of patient care.

There is a constant battle against time. We need time to make solid evaluations before and after operations. We are pushing the limits towards feeling uncomfortable. Definitely relating to quality of care. (Doctor A)

There were also experiences of stress in the operating room, a work place sanctuary where surgeons previously experienced that time was allowed to ‘stand still’.

Over the last years, operating programs have expanded. It is not seldom that we push really hard to get through the program. As we realize we are not making it, you feel how stress is building up also in the operating room. (Doctor A)

Quality of patient care as the basis for professional fulfilment

The participants expressed that quality of patient care was foundational for their experience of professional fulfilment. Some of the doctors emphasised how the two were mutually reinforcing.

Vital for job satisfaction is that we have an experience that things go well with our patients. (Doctor A)

The importance of continuity between the individual patient and the individual physician was also brought up as a central aspect of providing good care.

What gives me satisfaction is when I greet my patients, operate on them and follow up afterwards, so the patient is satisfied. That is all I wish for. (Doctor B)

Satisfied patients gave doctors a sense of accomplishment. A consequence was that a mistake made by a doctor that affected a patient discomposed the individual doctor.

A downside of being a surgeon are complications, it sort of comes with the job. I had a severe surgical complication last week and this is darkening everything, it affected me fundamentally for many days. (Doctor G)

Management not recognising quality of care challenges and providing limited support for doctor initiatives

The interviewed doctors experienced how the managerial focus on increasing volume conveyed an implicit assumption that more output, of the same quality, could be created by simply increasing the speed. This way of communicating about how to increase surgical volume created a strong dissonance with the everyday challenges experienced in the clinic.

Everyone expects that treatments are first class. We only measure waiting times and how soon we have written the discharge summary, and similar unimportant things. Everybody expects treatments to be the same and quality to be the same, no matter what. That is not true! (Doctor F)

A number of different individual initiatives to improve quality and facilitate everyday work had been initiated. One doctor described saving time and increasing quality and safety by making standard patient record templates for different operational procedures. Another doctor worked to schedule ward rounds to make them visible, instead of being something that the doctors were supposed to ‘squeeze in’ between other scheduled tasks.

We are measured on the number of operations we perform and on the number of patients we see in the outpatient clinic. But we are not measured on the time we spend on ward rounds. Talking with the doctor is a major part of what patients appreciate when measuring patient satisfaction. Now, ward rounds are scheduled. (Doctor G)

The participants expressed a sense of disappointment, and surprise, that the organisation neither seemed to appreciate the individual initiatives, nor provide a structure to go from the individual benefit towards benefiting the group of doctors. While many of the doctors had limited or no suggestions about what management ought to do differently, some suggested that the traditional hierarchical way of managing needs to be modernised.

I think this is about hospital management still struggling to find a more modern form. I find that teamwork is something that private enterprises have focused on for a long time. But the old way of leading is still what goes on in hospitals. With traditional hierarchies and top-down decisions. (Doctor A)

Several doctors experienced that management did not do enough to facilitate for doctors to participate in clinical development work. There were also some who clearly articulated the need for a major overhaul of the existing hospital culture, towards a situation where involvement from different employee groups was considered the norm.

If you are working with changes in such a fine-tuned and complex environment as a hospital, one must involve those affected by a change. You put small groups of surgeons and op-nurses together. Provide them some time to work on specific issues. Listen attentively to what they say about key pressure points and act accordingly. Not simply pushing decisions down at people! (Doctor A)

Discussion

This study explores how doctors experience the interactions among professional fulfilment, organisational factors and quality of patient care.

The participants described how providing quality of patient care was the single most important dimension contributing to their professional fulfilment. The interactions among professional fulfilment, organisational factors and quality of patient care were often experienced as resulting in complex and challenging situations. A doctor could be scheduled to operate while also having to run to the ward to check on patients, or run late to pick up children from daycare because shift times between operations ran longer than planned. The interviewed doctors primarily handled this tension individually by ‘stretching themselves’ and working around organisational hindrances in order to, no matter what, provide quality of patient care.

Quality of patient care is a key outcome for any healthcare organisation. One might consider that statement as self-evident. In particular when working as a doctor in a hospital that is part of the societal infrastructure in Norway, a well-functioning and affluent Nordic country. However, it might be prudent to remind ourselves that the amount of money available to spend on healthcare is limited. This restriction might be even clearer in a tax-financed healthcare system, like the Norwegian. There is thus a built-in tension that requires a constant balancing of clinical needs with budgetary means.

The participants expressed how conversations about quality of care were crowded out by production numbers and economic data. They conveyed that the essence of being a professionally fulfilled doctor, creating high-quality care for patients, no longer receives sufficient recognition.

This finding is in line with research pointing to changes in what society, patients and employers are expecting from a doctor, and how this is starting to create a job situation that is no longer what doctors expect.50 The research suggests that clinical leaders have a crucial role in supporting doctors to find meaning in a changing professional role.10 51 52 The inherent tension between an organisational focus on the bottom line and doctors’ focus on quality of patient care is found to increase the risk for experiencing meaninglessness, especially in combination with a lack of managerial recognition for work well done.53 According to this research, the interviewed doctors express an unfortunate combination of factors that are found to contribute to a sense of meaninglessness.

Faced with an accelerating struggle against time, the participants described ‘stretching themselves’ to deliver quality care despite organisational shortcomings. The experience of doctors having less time and more work is aligned with other studies.25 54–56 However, in our study, the participants describe how finding individual workarounds in order to handle organisational shortcomings, no longer is experienced as sustainable. Our participants relate how they have started to consider that quality of patient care, and their own well-being, both could suffer from this way of overextending themselves.

While limited time with patients was the primary concern, work–home balance was also an issue that troubled many of the participants. This is in line with recent studies in Sweden and Norway, where young doctors point to the importance of finding a job with good work–home balance.57 58 This view resonates with ‘downshifting’, a societal change defined by some researchers as an endorsement of the question, ‘In the last ten years, have you voluntarily made a long-term change in your lifestyle, other than planned retirement, which has resulted in you earning less money?’. More time with family was the most important reason for downshifting, followed by the desire to gain more control and personal fulfilment.59

That quality of patient care is foundational for professional fulfilment has been found in many previous studies.55 60–62 While the professional identity of doctors has long hinged on delivering good quality of patient care, more recently, the lack of physician well-being has been recognised as a potential threat to quality care.3 Research indicating a relationship between strain and stress in doctors and negative impact on quality and safety of patient care12 14 15 has also lead to an amendment of the Declaration of Geneva, as adopted by the World Medical Association in 2017: ‘I will attend to my own health, well-being and abilities in order to provide care of the highest standard’.63

The study participants experienced a hierarchical management culture and that management did not recognise quality of care challenges and provided limited support for doctor initiatives.

The respondents expressed frustrations with the limited possibility to participate in developing organisational policies, processes and systems. At the same time, there were few accounts of actual aspirations or doctors actively working to find solutions to organisational shortcomings. These findings are aligned with other research reporting that doctors’ engagement in development work has been a challenge.27 64 65 However, doctors who did engage had positive experiences from similar improvement initiatives and had experienced that also this type of work task contributed to their sense of professional fulfilment18 26 66

To involve doctors in development work, recognising their ideas and listening to understand what the difficulties are have been suggested as a central dimension to reduce burnout.25 67 A deliberate, collaborative process where managers commit scheduled doctor time for this type of work is key. What a manager says in conversations with the doctors and what a manager does really matter in relation to how clinicians participate in developing clinical policies, processes and systems.68–70 In order to support this process, organisational leaders in healthcare need to be attuned to how psychological and social needs relate to doctors’ motivation and engagement.70–72 In a participatory change study, where doctors analysed work-related problems and created local solutions that were then implemented, working conditions and patients’ perceived quality of care both showed positive changes.24 Another study showed that doctors who were actively involved in the process of changing the local ward round experienced better-informed clinical decisions, had fewer follow-up questions from their patients and increased their own professional fulfilment.73

Strengths and weaknesses of this study

This study included a feedback session where the researchers presented findings from analysing the interviews to the full group of doctors working at the surgical department. Both those who participated in interviews and several doctors who had not been interviewed confirmed the researchers’ understanding of the local work situation. This is a study strength that substantiates the findings. It confirms, in line with Malterud et al,46 that a limited number of information-rich interviews can contribute with new meaningful knowledge.

Having an interdisciplinary research group, with complimentary educational, research and work-related experiences analysing the interviews, contributed to a multifaceted and nuanced understanding of the empirical information.

In this study, we examine doctors’ perceptions about their work situation, without observing their actual behaviour. A potential weakness concerns if the interviewed doctors described their actual reality. Previous research has found that what people present in interviews reflect their perceptions, and these perceptions also inform their actions.43 74 By asking for clinical examples, we also strove to ensure close proximity to the local situation.

While this study focused on a single surgical setting, we suggest that other healthcare settings can learn from this study. We base this notion of transferability on research showing communality among doctors across different contexts75 by some researchers called one occupational community of practice.76

Conclusions

The interviewed doctors describe their struggle to balance the inherent tension among professional fulfilment, organisational factors and quality of patient care in their everyday work. They communicate how ‘stretching themselves’ to overcome organisational shortcomings is no longer a feasible strategy without compromising both professional fulfilment and quality of patient care. Managers need to ensure that doctors are involved when developing organisational policies, processes and systems. By including doctors, the lived experience of the inherent tension among professional fulfilment, organisational factors and quality of patient care is used in a meaningful way to improve organisational factors. This is likely to be beneficial for both professional fulfilment and quality of patient care.

Practice implications

Healthcare management has a central role in, and is responsible for, ensuring time and planned forums for doctors to engage and contribute in meaningful change. Engaging doctors in development work also challenges historical management practices, as this requires organisational leaders to consider how psychological and social needs contribute to individual doctor engagement and well-being.

Future research

This study has provided knowledge based on interviews with Norwegian doctors. It points to a need for future research to explore how the managerial side understands the interactions among professional fulfilment, organisational factors and quality of patient care.

Participatory interactive studies show positive effects from collecting doctors’ experiences, analysing the empirical material and feeding it back in a consolidated and actionable form. This external and structured view helps doctors and managers identify areas for local organisational change and facilitates the active involvement of doctors in the change process. There is a need for more research with participatory interactive methodologies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All four authors meet the conditions outlined in the ICMJE recommendations and have all contributed in all dimensions. Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. Final approval of the version published. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. There is no one who fulfils the criteria that has been excluded as an author.

Funding: This work was supported by Den norske legeforeningens fond for kvalitetsforbedring og pasientsikkerhet (Norwegian Fund for Quality Improvements and Patient Safety) grant number 16/5234. We confirm researcher independence from the funders and that all authors had full access to all data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data, the accuracy of the data analysis, results and conclusions.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Interview transcripts are the empirical source. These are only for the assigned research group in order to honour the commitment with interviewed physicians.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Berwick DM. Crossing the boundary: changing mental models in the service of improvement. Int J Qual Health Care 1998;10:435–41. 10.1093/intqhc/10.5.435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sikka R, Morath JM, Leape L. The quadruple aim: care, health, cost and meaning in work. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:608–10. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. West CP. Physician well-being: expanding the triple aim. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:458–9. 10.1007/s11606-016-3641-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Trockel M, Bohman B, Lesure E, et al. . A brief instrument to assess both burnout and professional fulfillment in physicians: reliability and validity, including correlation with self-reported medical errors, in a sample of resident and practicing physicians. Acad Psychiatry 2018;42:11–24. 10.1007/s40596-017-0849-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:573–6. 10.1370/afm.1713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hussey PS, Wertheimer S, Mehrotra A. The association between health care quality and cost: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:27–34. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-1-201301010-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leatt P, Baker GR, Halverson PK, et al. . Downsizing, reengineering, and restructuring: long-term implications for healthcare organizations. Front Health Serv Manage 1997;13:3–37. 10.1097/01974520-199704000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bourbonnais R, Brisson C, Malenfant R, et al. . Health care restructuring, work environment, and health of nurses. Am J Ind Med 2005;47:54–64. 10.1002/ajim.20104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nordang K, Hall-Lord ML, Farup PG. Burnout in health-care professionals during reorganizations and downsizing. A cohort study in nurses. BMC Nurs 2010;9:8 10.1186/1472-6955-9-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McKinlay JB, Marceau L. New wine in an old bottle: does alienation provide an explanation of the origins of physician discontent? Int J Health Serv 2011;41:301–35. 10.2190/HS.41.2.g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Firth-Cozens J, Greenhalgh J. Doctors' perceptions of the links between stress and lowered clinical care. Soc Sci Med 1997;44:1017–22. 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00227-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. West CP, Tan AD, Habermann TM, et al. . Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA 2009;302:1294–300. 10.1001/jama.2009.1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, et al. . Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:358–67. 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Angerer P, Weigl M. Physicians' psychosocial work conditions and quality of care: a literature review. Professions and Professionalism. 2015;5. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scheepers RA, Boerebach BC, Arah OA, et al. . A systematic review of the impact of physicians' occupational well-being on the quality of patient care. Int J Behav Med 2015;22:683–98. 10.1007/s12529-015-9473-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Le Grand J. Motivation, agency, and public policy: of knights and knaves, pawns and queens: Oxford University Press on Demand, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eijkenaar F, Emmert M, Scheppach M, et al. . Effects of pay for performance in health care: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Health Policy 2013;110:115–30. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lindgren Å, Bååthe F, Dellve L. Why risk professional fulfilment: a grounded theory of physician engagement in healthcare development. Int J Health Plann Manage 2013;28:e138–e57. 10.1002/hpm.2142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Khullar D, Chokshi DA, Kocher R, et al. . Behavioral economics and physician compensation--promise and challenges. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2281–3. 10.1056/NEJMp1502312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20., et al. The manager role in relation to the medical profession. 2012.

- 21. Shanafelt TD, Gorringe G, Menaker R, et al. . Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:432–40. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. von Knorring M, Alexanderson K, Eliasson MA. Healthcare managers' construction of the manager role in relation to the medical profession. J Health Organ Manag 2016;30:421–40. 10.1108/JHOM-11-2014-0192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bååthe F, Erik Norbäck L, Norback LE. Engaging physicians in organisational improvement work. J Health Organ Manag 2013;27:479–97. 10.1108/JHOM-02-2012-0043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weigl M, Hornung S, Angerer P, et al. . The effects of improving hospital physicians working conditions on patient care: a prospective, controlled intervention study. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:1 10.1186/1472-6963-13-401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc 2017;92:129–46. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dickson G. Anchoring physician engagement in vision and values: principles and framework. Saskatchewan: Regina Qu’Appelle Health Region, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Berwick DM, Nolan TW. Physicians as leaders in improving health care: a new series in Annals of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med 1998;128:289–92. 10.7326/0003-4819-128-4-199802150-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kaissi A. Enhancing physician engagement: an international perspective. Int J Health Serv 2014;44:567–92. 10.2190/HS.44.3.h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bååthe F. Physicians' engagement: qualitative studies exploring physicians' experiences of engaging in improving clinical services and processes [Doctoral thesis]: Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dyrbye LN, Trockel M, Frank E, et al. . Development of a research agenda to identify evidence-based strategies to improve physician wellness and reduce burnout. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:743–4. 10.7326/M16-2956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, et al. . In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med 2013;11:272–8. 10.1370/afm.1531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bringedal B. Styring for kvalitet og likebehandling. Norske legers syn på styringsinstrumentenes betydning. (Governance for quality and equity. Norwegian physicians' views on the effects of steering instruments.) : Aasen B, Prioritering, styring og likebehandling Utfordringer i norsk helsetjeneste. Oslo: Cappelen Akademiske, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 33. The Health Services Campaign. Helsetjenesteaksjonen. 2015. http://helsetjenesteaksjonen.no/ (Accessed 20 Dec 2018).

- 34. Nylenna M, Aasland O. Jobbtilfredshet blant norske leger [Job satisfaction among Norwegian doctors]. Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening 2010;130:1028–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Casalino LP, Crosson FJ. Physician satisfaction and physician well-being: should anyone care? 2015. 2015;5. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Aasland OG, Rosta J, Nylenna M. Healthcare reforms and job satisfaction among doctors in Norway. Scand J Public Health 2010;38:253–8. 10.1177/1403494810364559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hertzberg TK, Skirbekk H, Tyssen R, et al. . The hospital doctor of today - still continuously on duty. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2016;136:1635–8. 10.4045/tidsskr.16.0067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Aasland O, Rosta J. Hvordan har overlegene det? [The hospital consultant - how are they?] (In Norwegian). Overlegen 2011;1:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 39. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med 2018;283:516–29. 10.1111/joim.12752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. London: SAGE, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, et al. . Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q 2004;82:581–629. 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ellström PE, Rönnqvist D, Thunborg C. Omvärld, verksamhet och förändrade kompetenskrav inom hälso- och sjukvården: en studie av föreställningar hos centrala aktörer inom ett landsting: Linköpings universitet: Institutionen för pedagogik och psykologi, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Den kvalitativa forskningsintervjun (The Qualitative Research Interview). Lund: Studentlitteratur, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cooperrider D. The gift of new eyes: Personal reflections after 30 years of appreciative inquiry in organizational life. Research in organizational change and development. 2017:81.

- 45. Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook: SAGE Publications, Incorporated, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res 2016;26:1753–60. 10.1177/1049732315617444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 48. World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013;310:2191–4. 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. Lov om medisinsk og helsefaglig forskning (Helseforskningsloven=The Norwegian Health Research Act). https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2008-06-20-44. LOV-2008-06-20-44.

- 50. Edwards N, Kornacki MJ, Silversin J. Unhappy doctors: what are the causes and what can be done? BMJ 2002;324:835–8. 10.1136/bmj.324.7341.835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Royal College of Physicians. Doctors in society: medical professionalism in a changing world. Report of a Working Party of the Royal College of Physicians of London. 2005 London: RCP, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, et al. . A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: a guide for medical educators. Acad Med 2015;90:718–25. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bailey C, Madden A. What makes work meaningful - or meaningless. MIT Sloan management review. 2016;57:53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. . Burnout among health care professionals: a call to explore and address this underrecognized threat to safe, high-quality care. NAM Perspectives 2017;7 10.31478/201707b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. . Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy: RAND corporation. 2013. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56. Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. Lancet 2009;374:1714–21. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61424-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Diderichsen S. It’s just a job: a new generation of physicians dealing with career and work ideals: Umeå universitet, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hertzberg TK, Rø KI, Vaglum PJ, et al. . Work-home interface stress: an important predictor of emotional exhaustion 15 years into a medical career. Ind Health 2016;54:139–48. 10.2486/indhealth.2015-0134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hamilton C. Downshifting in Britain. A sea-change in the pursuit of happines. 2003:2.

- 60. Bovier PA, Perneger TV. Predictors of work satisfaction among physicians. Eur J Public Health 2003;13:299–305. 10.1093/eurpub/13.4.299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, et al. . Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: a prospective longitudinal study. JAMA 2006;296:1071–8. 10.1001/jama.296.9.1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bliss M. William Osler: a life in medicine. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Parsa-Parsi RW. The revised declaration of Geneva: a modern-day physician’s pledge. JAMA 2017;318:1971–2. 10.1001/jama.2017.16230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bååthe F, Norbäck LE, Erik Norbäck L. Engaging physicians in organisational improvement work. J Health Organ Manag 2013;27:479–97. 10.1108/JHOM-02-2012-0043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lee TH, Cosgrove T. Engaging doctors in the health care revolution. United States: Harvard Business School Publ. Corp 2014:104–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Davies H, Powell A, Rushmer R. Why don’t clinicians engage with quality improvement? J Health Serv Res Policy 2007;12:129–30. 10.1258/135581907781543139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Swensen S, Kabcenell A, Shanafelt T. Physician-organization collaboration reduces physician burnout and promotes engagement: the mayo clinic experience. J Healthc Manag 2016;61:105–27. 10.1097/00115514-201603000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Stacey R. The tools and techniques of leadership and management: meeting the challenge of complexity. London: Routledge, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Stacey RD, Mowles C. Strategic management and organisational dynamics: the challenge of complexity to ways of thinking about organisations. Harlow, United Kingdom: Pearson Education, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Swensen SJ, Shanafelt T. An organizational framework to reduce professional burnout and bring back joy in practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2017;43:308–13. 10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Herzberg F. One more time: How do you motivate employees: Harvard Business Review Boston, MA. 1968. [PubMed]

- 72. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol 2000;55:68–78. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Baathe F, Ahlborg Jr G, Lagström A, et al. . Physician experiences of patient-centered and team-based ward rounding–an interview based case-study. J Hosp Adm 2014;3:127. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Czarniawska B. Narratives in social science research. London: SAGE, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Van Maanen J, Barley SR. Occupational communities: culture and control in organizations. Res Organ Behav 1984:287–365. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wenger E. Communities of practice and social learning systems. Organization 2000;7:225–46. 10.1177/135050840072002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026971supp001.pdf (245.2KB, pdf)