Abstract

Objective

Harmful use of alcohol represents a large socioeconomic and disease burden and displays a socioeconomic status (SES) gradient. Several alcohol control laws were devised and implemented, but their equity impact remains undetermined.

We ascertained if an SES gradient in hazardous alcohol consumption exists in Geneva (Switzerland) and assessed the equity impact of the alcohol control laws implemented during the last two decades.

Design

Repeated cross-sectional survey study.

Setting

We used data from non-abstinent participants, aged 35–74 years, from the population-based cross-sectional Bus Santé study (n=16 725), between 1993 and 2014.

Methods

SES indicators included educational attainment (primary, secondary and tertiary) and occupational level (high, medium and low). We defined four survey periods according to the implemented alcohol control laws and hazardous alcohol consumption (outcome variable) as >30 g/day for men and >20 g/day for women.

The Slope Index of Inequality (SII) and Relative Index of Inequality (RII) were used to quantify absolute and relative inequalities, respectively, and were compared between legislative periods.

Results

Lower educated men had a higher frequency of hazardous alcohol consumption (RII=1.87 (1.57; 2.22) and SII=0.14 (0.11; 0.17)). Lower educated women had less hazardous consumption ((RII=0.76 (0.60; 0.97)and SII=−0.04 (−0.07;−0.01]). Over time, hazardous alcohol consumption decreased, except in lower educated men.

Education-related inequalities were observed in men in all legislative periods and did not vary between them. Similar results were observed using the occupational level as SES indicator. In women, significant inverse SES gradients were observed using educational attainment but not for occupational level.

Conclusions

Population-wide alcohol control laws did not have a positive equity impact on hazardous alcohol consumption. Targeted interventions to disadvantaged groups may be needed to address the hazardous alcohol consumption inequality gap.

Keywords: socioeconomic factors, inequality, hazardous alcohol consumption, alcohol control laws, education, occupation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Relatively large cross-sectional study spanning 20 years.

Use of relative and absolute inequality regression-based measures.

Equity impact of several alcohol control measures was evaluated.

No longitudinal data to clearly assess causality.

Possible confounding by the 2008 economic crisis cannot be excluded.

Introduction

Harmful use of alcohol is responsible for a large social, economic and disease burden. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), harmful use of alcohol is estimated to represent 5.9% of worldwide mortality, accounting for 3.3 million deaths per year. Additionally, the global burden of disease and injury attributed to alcohol represents 5.1% of the total disability-adjusted life years, being in the origin of an excess of 200 injury and disease conditions.1 Both mortality and morbidity related to alcohol consumption have increased over time.2–4

Considering the high burden of disease attributed to alcohol consumption, several legislative interventions were advocated by WHO5 and by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Many of these interventions aiming at the reduction of harmful consumption were implemented in several countries and were met with considerable success.6

As in other harmful behaviours, a social gradient in alcohol consumption was identified, with higher consumption existing in individuals with lower socioeconomic status (SES).7–9 Also, its effects on health are socially patterned with higher alcohol-related mortality in low-educated individuals and manual workers,10 and alcohol-related mortality significantly associated with the rise of unemployment rates.11 Some institutions, like WHO, have set practical measures to prevent the widening of alcohol-related inequalities and, ideally, to reduce them. Policies, such as alcohol taxation and price rising, age limits for purchase and drink-driving, and restriction of alcohol marketing, advertising and promotion, coupled with interventions for heavy drinkers and vulnerable groups are among those suggested.12 However, the impact of these policies on SES inequalities in alcohol consumption remains to be determined. Existing studies mainly focus on the equity impact of taxation policies with results suggesting that tax increases have a strong pro-equity effect, particularly for those with higher alcohol consumption.13 14

In Geneva (Switzerland), several alcohol control laws were implemented during the last two decades.15 In 2000, an alcohol advertising ban was introduced, while in 2004, there was a threefold increase in prices of alcopop beverages (eg, premixed drinks), a decrease in the alcohol driving limit, an off-premise sale interdiction between 21:00 and 7:00 hours, and an alcohol sale interdiction in video stores and gas stations. Smoking bans were suggested to reduce alcohol demand,16 17 and such a ban was implemented in Geneva in 2009. A recent study15 showed a decrease in overall alcohol consumption and in hazardous drinking, in men and women in Geneva between 1993 and 2014, independently of policy changes. Still, differential impact according to SES was not assessed.

The main aim of this study was, first, to determine if an SES gradient in hazardous alcohol consumption exists in the adult population of Geneva and, second, to assess the impact of the implemented alcohol control policies on this gradient, if any. As a secondary aim, we also sought to determine the impact of the successive legislative interventions on inequalities of total daily alcohol consumption, if they existed.

Methods

Participants

We used data from the Bus Santé study, a continuing population-based study in the State of Geneva (population of approximately 490 000 inhabitants in 2016) monitoring health and associated risk factors. As previously described,18 independent samples of residents were subjected to annual health examination surveys since 1993. A resident list provided by the local authorities was used to select participants who were aged 35–74 years until 2011 and 20–74 years afterwards. Gender and 10-year age strata were used for stratified random sampling. Each participant was invited to a Bus Santé study unit where trained collaborators would administer the questionnaires. One of the three study units was a mobile unit visiting different areas of the Geneva canton while the other two were based at the Geneva University Hospitals.

Individuals who did not respond to the invitation were telephoned up to seven times at different days of the week and times of the day. If contact was not established, two extra invitations were mailed. When participants were unreachable, they were considered as non-responders and replaced.

Participation rate varied with 60.1% for 1996–2003, 56.2% for 2004–2009 and 50.8% for the 2010–2014 period. Participant recruitment decreased during the period between 2005 and 2008 due to a simultaneous study taking place with shared logistical resources but not focusing on the same population.

Exclusion criteria

We included participants with ages between 35 and 74 years, the age group consistently recruited during the entirety of the Bus Santé study. We excluded abstinent participants (n=3059, 15.2%) and those with missing data on educational attainment (n=368, 2.2%), assumed to be missing completely at random. For occupational level analysis, participants who were not working (unemployed n=789, 4.7%; retired n=2753, 16.4% and housewives/househusbands n=1635, 9.7%) or with missing for this variable (n=257, 1.5%) were also excluded.

Outcome variable

The main outcome variable was hazardous alcohol consumption (>30 g/day for men and >20 g/day for women) established based on data from total daily alcohol intake in g/day. Hazardous alcohol consumption was defined according to the Swiss Institute for Alcohol and Drug Prevention guidelines in 2017 (http://www.iard.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Drinking-Guidelines-General-Population.pdf) and like previous studies on Swiss alcohol consumption.19 Total daily alcohol intake was determined using a validated Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ), as previously described,15 taking into account consumption frequency, type of alcoholic beverage (wine, champagne, beer, aperitifs such as anisette or martini and spirits like liqueur, brandy or whisky) and average serving size compared with a 10 g alcohol standard for each beverage (similar, bigger or smaller). The same FFQ was used throughout the totality of the study, with the resulting data having incorporated large international consortia.20

Covariates

We created a categorical variable identifying participants who were surveyed during periods that differed in the implemented alcohol control laws: period 1 (before 20 October 2000, baseline), period 2 (from 20 October 2000 to 1 February 2004—introduction of advertising ban), period 3 (from 2 February 2004 to 31 October 2009–300% increase in alcopop price, decrease of legal alcohol driving limit, off-premise sale interdiction of alcoholic beverages from 21:00 to 7:00 hours and gas stations and video stores are no longer allowed to sell alcohol) and period 4 (from 1 November 2009 onwards—implementation of a public smoking ban).

As in Huisman et al,21 we considered educational attainment in three levels: (1) primary—no end of school certification (‘Maturité’) or no professional apprenticeship, (2) secondary—obtaining ‘Maturité’ or professional apprenticeship and (3) tertiary (university degree).

Current occupation was categorised into three categories according to the British Registrar General’s Scale22: high (professional and intermediate professions), medium (non-manual occupations) and low (manual or lower occupations).

Age was used as a continuous variable; smoking status was classified into never smokers, current smokers and ex-smokers, and nationality as Swiss or other.

Statistical analysis

For descriptive statistics, continuous variables are presented as mean±SD deviation (SD) while categorical ones as absolute and relative frequencies.

X2 test of independence and one-way analysis of variance were used to assess the significance of group differences in categorical and continuous variables, respectively. All analyses were stratified by gender. Outcome proportions in different survey years, as displayed in figure 1 and online supplementary figure 1, were age adjusted using the age distribution of the Swiss population in 2014 (https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/population.html).

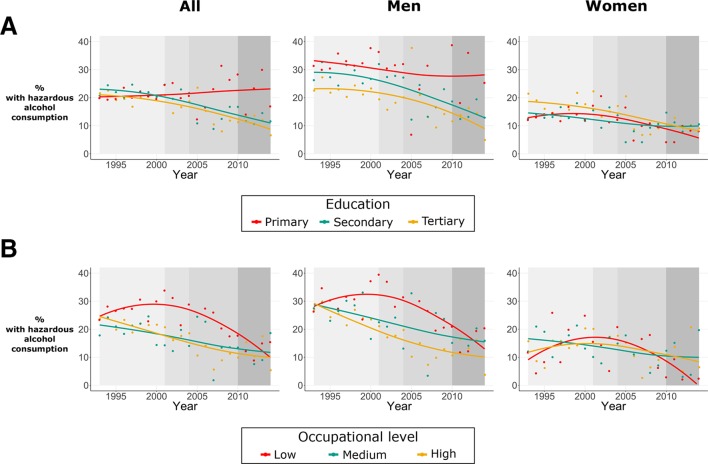

Figure 1.

Age-adjusted proportions of participants with hazardous alcohol consumption stratified by gender and (a) educational attainment and (b) occupational level. Trends were obtained using locally waited scatterplot smoothing. Each shaded period represents one of the periods with different alcohol control laws.

bmjopen-2019-028971supp002.pdf (544.8KB, pdf)

Time-series analyses were performed (overall and stratified by educational attainment or occupational level), using adjusted linear (for total consumption) or binomial (for hazardous consumption) regression models. Coefficients for the calendar year variable are reported.

Poisson regression models were used to test the association between exposure (educational attainment and occupational level) and outcome variables (hazardous alcohol consumption and total daily alcohol consumption), and to estimate prevalence ratios (PRs). Besides age, nationality and smoking status, models were also adjusted for survey date in calendar years to take secular trends into account.23–25

We used the STATA package RIIGEN26 27 to calculate SES variables adjusted for group size and relative SES position using a ridit scoring method. These variables were then used to calculate the Slope Index of Inequality (SII) and the Relative Index of Inequality (RII) which quantify absolute and relative differences between SES-defined strata, respectively. For total daily alcohol consumption, a continuous outcome variable, we chose to only calculate the SII since it is more interpretable than a relative measure in this context and this was not the main outcome variable of the study.

These regression-based indexes describe differences between the SES extremes taking into account the intermediate categories.27 For instance, RII=1.3 represents an added 30% outcome prevalence in the lowest SES group compared with the highest, similar to a PR. SII, an impact measure, indicates the absolute difference in outcome prevalence between lowest and highest SES groups. For example, SII=0.3 indicates 30 more individuals with the outcome per 100 individuals in the lowest SES group compared with the highest one. When used with continuous variables, as total alcohol consumption, SII=4 would indicate an excess consumption of 4 g/day in the lowest SES group when compared with the highest.

Both indexes were calculated for each of the four periods and compared between them using pairwise Wald tests.

Sensitivity analyses of the educational attainment and the occupational level-based models were performed through adjustment for a second SES indicator (occupational level or educational attainment, respectively). Adjustment of educational attainment model by occupational level included non-working individuals: retired, unemployed and housewives/househusbands. Reciprocal adjustment did not change the overall trends (sensitivity analyses can be found in online supplementary tables 1–3). A sensitivity analysis for interperiod differences in SES inequalities indexes was also performed through testing for significant interactions between the RIIGEN-generated SES variables and legislative period (online supplementary table 4).

bmjopen-2019-028971supp001.pdf (544.8KB, pdf)

Data were analysed using STATA V.13.1 and R V.3.2.2.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in developing the research question, study design or outcome measures. While direct dissemination of study results has not been planned, they will be communicated through our institutional media services.

Results

Characteristics of participants

Forty-three per cent of participants were surveyed in period 1, 21.2% in period 2, 14.8% in period 3 and 21.1% in period 4.

The participant characteristics stratified by gender and educational attainment can be found in table 1. For education-based analyses, we included 16 725 participants of which 18.0% had primary education, 45.0% secondary education and 37.0% tertiary education. The mean daily consumption of alcohol was 15.9±18.9 g/day and 18.2% were found to have hazardous alcohol consumption. When stratified by gender and educational attainment, higher educated participants of both genders were younger and less probably current smokers. Furthermore, daily alcohol consumption and the proportion of participants with hazardous alcohol consumption were higher in lower educated men, while no differences could be observed in women.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics according to educational attainment and gender (1993–2014, Bus Santé study, state of Geneva, Switzerland)

| Overall | Men | Women | |||||||

| Primary education | Secondary education | Tertiary education | P value | Primary education | Secondary education | Tertiary education | P value | ||

| N (%) | 16 725 (100) | 1257 (14.7) | 4119 (48.2) | 3173 (37.1) | 1750 (21.4) | 3414 (41.8) | 3012 (36.8) | ||

| Age, mean±SD | 52.1±10.6 | 52.8±10.9 | 52.8±10.7 | 51.0±10.6 | <0.001 | 54.6±10.6 | 52.9±10.4 | 49.8±10.1 | <0.001 |

| Swiss nationality, (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| No | 4704 (28.1) | 690 (54.9) | 964 (23.4) | 1054 (33.2) | 561 (32.1) | 568 (16.6) | 867 (28.8) | ||

| Yes | 12 013 (71.9) | 567 (45.1) | 3152 (76.6) | 2116 (66.8) | 1189 (67.9) | 2846 (83.4) | 2143 (71.2) | ||

| Total alcohol consumption (g/day), mean±SD | 15.9±18.9 | 26.3±24.7 | 22.3±23.2 | 17.8±18.1 | <0.001 | 10.7±13.3 | 10.0±12.7 | 10.2±12.7 | 0.22 |

| Hazardous alcohol consumption, (%) | <0.001 | 0.62 | |||||||

| No | 13 676 (81.8) | 840 (66.8) | 3089 (75.0) | 2641 (83.2) | 1510 (86.3) | 2979 (87.3) | 2617 (86.9) | ||

| Yes | 3049 (18.2) | 417 (33.2) | 1030 (25.0) | 532 (16.8) | 240 (13.7) | 435 (12.7) | 395 (13.1) | ||

| Smoking status, (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| Never smoker | 6812 (42.5) | 379 (30.2) | 1356 (33.0) | 1403 (44.3) | 819 (53.1) | 1441 (46.2) | 1414 (50.1) | ||

| Current smoker | 3829 (23.9) | 382 (30.4) | 1154 (28.0) | 625 (19.7) | 355 (23.0) | 794 (25.4) | 519 (18.4) | ||

| Ex-smoker | 5385 (33.6) | 496 (39.5) | 1605 (39.0) | 1140 (36.0) | 368 (23.9) | 886 (28.4) | 890 (31.5) | ||

| Law package period, (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| Period 1 (before 20 October 2000) | 7187 (43.0) | 587 (46.7) | 1914 (46.5) | 1120 (35.3) | 1022 (58.4) | 1429 (41.9) | 1115 (37.0) | ||

| Period 2 (20 October 2000 to 1 February 2004) | 3550 (21.2) | 269 (21.4) | 905 (22.0) | 632 (19.9) | 372 (21.3) | 707 (20.7) | 665 (22.1) | ||

| Period 3 (2 February 2004 to 31 October 2009) | 2467 (14.8) | 178 (14.2) | 571 (13.9) | 535 (16.9) | 186 (10.6) | 501 (14.7) | 496 (16.5) | ||

| Period 4 (after 31 October 2009) | 3521 (21.1) | 223 (17.7) | 729 (17.7) | 886 (27.9) | 170 (9.7) | 777 (22.8) | 736 (24.4) | ||

For the occupational level analysis, we included 11 659 working participants and their characteristics are reported in online supplementary table 5. Similarly to the educational attainment stratification, lower alcohol consumption and lower proportion of consumption at risk were found in men with high occupational level and no differences were observed among women.

Time trends of hazardous alcohol consumption

Alcohol consumption (online supplementary figure 2a) and the proportion of drinkers with hazardous consumption (online supplementary figure 2b) have decreased in both genders between 1993 and 2014 (online supplementary table 6). Yet, when time trends were stratified by educational attainment, we observed that the decrease has not occurred similarly across all educational attainment-related groups, since men with primary education did not display a reduction in hazardous alcohol consumption like their counterparts with secondary and tertiary education (figure 1A). However, when using the occupational level as an SES indicator, after an initial increase in hazardous consumption in participants with low occupational level, a decrease could be observed in later periods (figure 1B). To test if the observed time trends were not due to differences in participant characteristics other than educational attainment and occupational level, data were fitted into multivariable binomial models to obtain adjusted time trends (online supplementary table 6). We identified negative adjusted time trends for both outcomes, in both genders (βhazardous consumption in men=-0.04 (-0.04;−0,03) p<0.001, βhazardous consumption in women=-0.04 (−0.05;−0,03) p<0.001). As suggested by figure 1A and online supplementary table 6, adjusted time trend analysis stratified by educational attainment showed that hazardous consumption did not change among men with primary education (βprimary=−0.00 (−0.02; 0.02) p=0.75), while it decreased among men with secondary or tertiary education (βsecondary=−0.04 (−0.06; −0.03) p<0.001; βtertiary=−0.05 (−0.06; −0.03) p<0.001). For women, the time trends were all negative. Analyses stratified by occupational level revealed a harmonious decrease in hazardous alcohol consumption in all levels and for both genders (online supplementary table 6).

bmjopen-2019-028971supp003.pdf (487.3KB, pdf)

Similar results were observed when total daily alcohol intake was used as the outcome variable (online supplementary figure 1a,b and table 6). However, contrarily to hazardous alcohol consumption for which no inequalities in women were observed in any of the periods, significant inequalities favouring the lower SES groups were observed in periods 1 and 3 (online supplementary figure 3).

bmjopen-2019-028971supp004.pdf (918.6KB, pdf)

Association between educational attainment, occupational-level and hazardous alcohol consumption

We observed more hazardous consumption in lower educated men (PRprimary vs tertiary=1.58 (1.39; 1.80) p<0.001, PRsecondary vs tertiary=1.32 (1.18; 1.47) p<0.001) with this being reflected in the relative and absolute indexes of inequality (RII=1.87 (1.57; 2.22) p<0.001 and SII=0.14 (0.11; 0.17) p<0.001, respectively) (table 2). On the other hand, lower education was associated with less hazardous consumption in women (RII=0.76 (0.60; 0.97) p=0.026 and SII=−0.04 (−0.07; −0.01) p=0.008) (table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence ratio, RII and SII of educational attainment and occupational level as determinants of hazardous alcohol consumption

| Men | Women | |||

| Estimate (95% CI) | P value | Estimate (95% CI) | P value | |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| Prevalence ratio | ||||

| Primary versus tertiary | 1.58 (1.39 to 1.80) | P<0.001 | 0.84 (0.70 to 1.00) | 0.048 |

| Secondary versus tertiary | 1.32 (1.18 to 1.47) | P<0.001 | 0.86 (0.74 to 0.99) | 0.035 |

| RII (least to most educated) | 1.87 (1.57 to 2.22) | P<0.001 | 0.76 (0.60 to 0.97) | 0.026 |

| SII (least to most educated) | 0.14 (0.11 to 0.17) | P<0.001 | −0.04 (−0.07 to −0.01) | 0.008 |

| Occupational level | ||||

| Prevalence ratio | ||||

| Low versus high | 1.4 (1.24 to 1.59) | P<0.001 | 1.09 (0.81 to 1.45) | 0.58 |

| Medium versus high | 1.07 (0.93 to 1.24) | 0.31 | 0.83 (0.70 to 1.00) | 0.053 |

| RII (low to high) | 1.68 (1.38 to 2.06) | P<0.001 | 0.86 (0.62 to 1.20) | 0.38 |

| SII (low to high) | 0.11 (0.07 to 0.15) | P<0.001 | −0.02 (−0.05 to 0.02) | 0.30 |

Adjusted for age, nationality, smoking status and survey date.

RII, Relative Index of Inequality; SII, Slope Index of Inequality.

An occupational level-related gradient was observed in men, those with lower occupational level having a higher proportion of hazardous consumption (RII=1.68 (1.38; 2.06) p<0.001 and SII=0.11 (0.07; 0.15) p<0.001) (table 2). Conversely, no such gradient was found in women (table 2).

Similar findings were obtained for total daily alcohol intake, except for women with a lower occupational level which displayed lower daily alcohol consumption (online supplementary table 7).

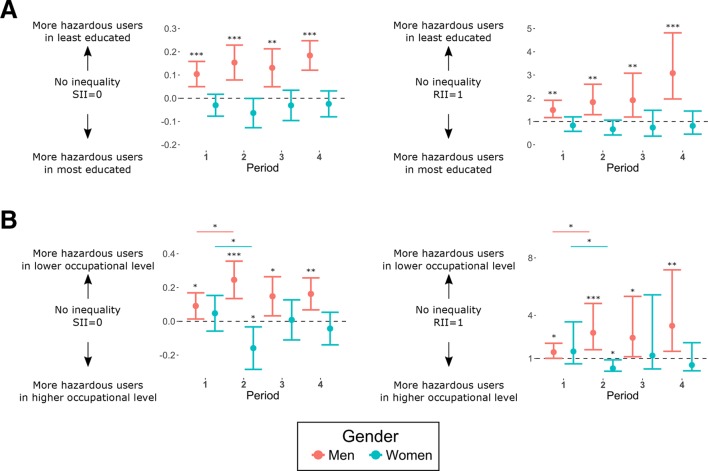

Alcohol laws, alcohol consumption and SES inequalities

In men, we identified absolute and relative education-related inequalities in hazardous alcohol consumption in all periods and favouring the most educated (figure 2A, online supplementary table 8). No differences between successive periods were observed (p>0.05) (figure 2A). In women, no education-related inequalities were observed during the various legislative periods (figure 2A, online supplementary figure 1).

Figure 2.

Absolute (SII) and relative (RII) inequalities in hazardous alcohol consumption for men (red) and women (blue) for (a) educational attainment and (b) occupational level. Estimates and 95% CIs are presented as well as the level of significance. Wald test p values comparing indexes between groups are presented when <0.05. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. RII, Relative Index of Inequality; SII, Slope Index of Inequality.

Occupational level-related inequalities in men were also observed in absolute and relative terms and increased between period 1 and 2 (p<0.05), remaining constant thereafter (figure 2B, online supplementary table 8).

In women, inequalities in favour of those with lower occupational level were only observed in period 2, with an increase being observed between period 1 and 2 (p<0.05) (figure 2B, online supplementary table 8).

Similar results were obtained concerning daily alcohol intake (online supplementary figure 3a,b and table 8).

Time trend interaction-based sensitivity analysis for education-related inequalities identified a difference in relative inequalities in period 4 (compared with the reference period 1), which seemed to increase (interaction=2.2 (1.3; 3.6), p=0.002, online supplementary table 4). The same analysis using occupation level as SES indicator identified the differences mentioned above between period 1 and 2 in both genders, but also an increase in relative inequalities in men in period 4 (interaction=2.6 (1.1; 6.2), p=0.02, online supplementary table 4).

Discussion

We identified a social gradient in alcohol drinking patterns among men, with lower SES being associated with a higher proportion of hazardous consumption and higher total daily alcohol consumption. In women, a less pronounced inverse gradient was observed with higher SES being associated with higher hazardous consumption and higher total daily consumption. Differently from men for whom the inequalities in hazardous consumption were observed using both SES indicators, in women the inequalities were only related to educational attainment.

These patterns were also found in other studies: low education and manual occupation males tend to have a higher prevalence of alcohol consumption, contrarily to women.6 7 This gender discrepancy in inequalities suggests that different mechanisms, other than those related to SES, are behind hazardous alcohol consumption in each of the genders. While the reasons behind this discrepancy are still elusive, it is possible that like tobacco smoking,28 among women, alcohol consumption started to be seen as a symbol of increased SES and emancipation.29 30 Like the tobacco industry, the alcohol industry seems to be exploiting this fact.31 As such, policies to address inequalities in alcohol consumption should be gender adapted and informed by further studies on their nature.

We also observed a discrepancy between time trends when educational attainment or occupational level was used as SES indicators. Sensitivity analyses showed that this was not due to the educational attainment-based analysis including non-working participants. SES indicators such as education and occupational level often display low to moderate correlations and cannot be used interchangeably.32–34 Furthermore, each indicator may be related to different causal mechanisms and can be differentially associated with a specific health-related outcome.32 It is thus possible that lower education has a wider impact on other SES-related determinants of persistent alcohol consumption than occupation, justifying the observed discrepancies in alcohol consumption trends.

Differently from previous studies, we studied the evolution of alcohol drinking patterns during a 22-year period. Though hazardous consumption decreased in both genders, inequalities in alcohol consumption remained stable among men, with relative inequalities in men potentially increasing during the latter period of the study when compared with earlier ones. No specific inequality patterns were identified for the periods with different legislative alcohol control measures (advertising ban, a threefold increase in alcopop price, a decrease of legal alcohol driving limit and ban of the off-premise sale of alcoholic beverages from 21:00 to 7:00 hours and at gas stations and video stores). The lack of equity impact of these measures can potentially be explained in light of the recommendations and reports by WHO12 and OECD.6 Though these institutions recommend raising the taxes of all alcoholic products, the OECD described Switzerland as having mild alcohol taxation with some of the lowest taxes on beer and wine.6 Moreover, increasing the tax on an alcoholic product does not directly reduce consumption, since it does not guarantee an increase in the final price of the product, or a relevant price increase considering the populations’ purchasing power. A recent report pointed out that price increases due to taxation were regressive measures in nature, with a bigger financial burden on individuals with low SES, thus with a potential positive equity impact.35 However, this study was mainly based on data from low-income/middle-income countries where the majority of consumers belong to high SES strata. Lack of data concerning high-income countries precluded the same analysis in this context. Our results suggest that the increase in tax on alcopop beverages did not have a positive equity impact in hazardous alcohol consumption and further increases in taxation of other alcoholic products are probably needed. Also, easy circulation between neighbouring regions and countries may have allowed smuggling of beverages to a lower price. This is particularly relevant for regions like Geneva due to its proximity to the France-Switzerland border. Finally, and even though our study covered a relatively long period, legislative measures may have a delayed impact in time, not observable in the time span of this study.

Strengths

We analysed a population-based sample of participants from a single region spanning a 22-year period. This relatively homogeneous sample allowed us to measure alcohol consumption and its inequalities in this population and to follow them in different periods according to which alcohol control laws were implemented. We used two SES indicators (educational attainment and occupational level) and the lack of effect of alcohol control measures on inequalities based on both indicators further increases the robustness of our findings. Furthermore, we measured inequalities and their trends complementing the relative with absolute measures in order to determine the impact that interventions to reduce inequalities could have had on the outcomes.27 36

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, it was based on self-reported repeated cross-sectional data instead of longitudinal, not allowing the follow-up of alcohol consumption and its inequalities at the individual level. Second, the participation rate, as in another cross-sectional survey studies, ranged between 51% and 60%, and, accordingly, selection bias cannot be excluded. Third, strong enforcement and coordinated multilevel approach are capital for effective implementation of alcohol control laws. Unfortunately, we could not evaluate the degree of law enforcement as no data on measure adoption were available, and we were not able to control for the price trends of the alcoholic products. Also, the implemented laws could have had a differential effect on population subgroups defined by factors other than SES indicators. The mental and general health status of the participants was also not taken into account and confounding by these variables cannot be excluded. The effects of each legislative package could have been delayed in time and appeared on subsequent periods or even beyond the time frame of this study. Moreover, the time span of this study included the 2008 economic crisis, which may have impacted on alcohol consumption and its inequalities, as noted by Stuckler et al.11 Finally, besides confounding by other unrecorded factors, our study is based on a single region of a high-income country, probably limiting the generalisability of the findings to settings that differ greatly from Geneva.

Conclusion

In the male adult population of Geneva, SES inequalities in hazardous alcohol consumption were identified, favouring the better off. An inverse, but less pronounced SES gradient was observed in women. The successive antialcohol legislation implemented in the last 20 years was unable to reduce the SES inequalities in men. To close the inequality gap in this harmful behaviour in settings similar to Geneva, evaluating the equity impact of legislative interventions and using adjuvant targeted measures could be of great importance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Bus Santé study participants whose data has made this study possible.

Footnotes

JLS and TL contributed equally.

Contributors: JLS and TL: conceptualisation, analysis and interpretation of results, manuscript writing and revision. J-MT, TF-C, BB, J-MG, PM-V: data collection, interpretation of results, manuscript reviewing and final editing the manuscript. IG: conceptualisation, data collection, interpretation of results, manuscript writing and revision.

Funding: The Bus Santé study is funded by the General Directorate of Health, Canton of Geneva, Switzerland and the Geneva University Hospitals.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Bus Santé study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, was granted approval by the Institute of Ethics Committee of the University of Geneva.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Consent has not been obtained to share the data publicly. However, data may be accessed on contacting the corresponding author. The same principle applies for statistical analysis scripts.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. : Poznyak V, Rekve D, Global status report on alcohol and health, 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization - Management of Substance Abuse Unit, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. GBD. Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1659–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. GBD. Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017;390:1345–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Forouzanfar MH, Alexander L, Anderson HR, et al. . Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;386:2287–323. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00128-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. WHO. European action plan to reduce the harmful use of alcohol 2012-2020. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization - Regional office for Europe, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sassi F, Tackling Harmful Alcohol Use: OECD Publishing, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bloomfield K, Grittner U, Kramer S, et al. . Social inequalities in alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems in the study countries of the EU concerted action ’Gender, Culture and Alcohol Problems: a Multi-national Study'. Alcohol Alcohol Suppl 2006;41:i26–i36. 10.1093/alcalc/agl073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuntsche E, Rehm J, Gmel G. Characteristics of binge drinkers in Europe. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:113–27. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, et al. . WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet 2012;380:1011–29. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61228-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mackenbach JP, Kulhánová I, Bopp M, et al. . Inequalities in alcohol-related mortality in 17 european countries: a retrospective analysis of mortality registers. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001909 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stuckler D, Basu S, Suhrcke M, et al. . The public health effect of economic crises and alternative policy responses in Europe: an empirical analysis. Lancet 2009;374:315–23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61124-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Loring B. Alcohol and inequities: guidance for addressing inequities in alcohol-related harm. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Meier PS, Holmes J, Angus C, et al. . Estimated effects of different alcohol taxation and price policies on health inequalities: a mathematical modelling study. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1001963 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Holmes J, Meng Y, Meier PS, et al. . Effects of minimum unit pricing for alcohol on different income and socioeconomic groups: a modelling study. Lancet 2014;383:1655–64. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62417-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dumont S, Marques-Vidal P, Favrod-Coune T, et al. . Alcohol policy changes and 22-year trends in individual alcohol consumption in a Swiss adult population: a 1993-2014 cross-sectional population-based study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014828 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kasza KA, McKee SA, Rivard C, et al. . Smoke-free bar policies and smokers' alcohol consumption: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Drug Alcohol Depend 2012;126:240–5. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Picone GA, Sloan F, Trogdon JG. The effect of the tobacco settlement and smoking bans on alcohol consumption. Health Econ 2004;13:1063–80. 10.1002/hec.930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guessous I, Bochud M, Theler JM, et al. . 1999-2009 Trends in prevalence, unawareness, treatment and control of hypertension in Geneva, Switzerland. PLoS One 2012;7:e39877 10.1371/journal.pone.0039877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gmel G, Klingemann S, Müller R, et al. . Revising the preventive paradox: the Swiss case. Addiction 2001;96:273–84. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96227311.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Shi P, et al. . Global, regional, and national consumption levels of dietary fats and oils in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis including 266 country-specific nutrition surveys. BMJ 2014;348:g2272 10.1136/bmj.g2272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huisman M, Kunst AE, Mackenbach JP. Educational inequalities in smoking among men and women aged 16 years and older in 11 European countries. Tob Control 2005;14:106–13. 10.1136/tc.2004.008573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Leete R, Fox J. Registrar Generals social classes: origins and uses. Population trends 1977;8:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Agaku IT, King BA, Dube SR. Current cigarette smoking among adults - United States, 2005-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63:29–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Regidor E, Pascual C, Giráldez-García C, et al. . Impact of tobacco prices and smoke-free policy on smoking cessation, by gender and educational group: Spain, 1993-2012. Int J Drug Policy 2015;26:1215–21. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Becker GS, Grossman M, Murphy KM. An empirical analysis of cigarette addiction. American Economic Review 1994;84:396–418. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kroll LE. RIIGEN: stata module to generate variables to compute the relative index of inequality. Boston College Department of Economics 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE. Measuring the magnitude of socio-economic inequalities in health: an overview of available measures illustrated with two examples from Europe. Soc Sci Med 1997;44:757–71. 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00073-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Amos A, Haglund M. From social taboo to "torch of freedom": the marketing of cigarettes to women. Tob Control 2000;9:3–8. 10.1136/tc.9.1.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Emslie C, Hunt K, Lyons A. Transformation and time-out: the role of alcohol in identity construction among Scottish women in early midlife. Int J Drug Policy 2015;26:437–45. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Eriksen S. Alcohol as a gender symbol. Scand J Hist 1999;24:45–73. 10.1080/03468759950115845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lyons AC, Dalton SI, Hoy A. ’Hardcore drinking': portrayals of alcohol consumption in young women’s and men’s magazines. J Health Psychol 2006;11:223–32. 10.1177/1359105306061183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Geyer S, Hemström O, Peter R, et al. . Education, income, and occupational class cannot be used interchangeably in social epidemiology. Empirical evidence against a common practice. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:804–10. 10.1136/jech.2005.041319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Muller A. Education, income inequality, and mortality: a multiple regression analysis. BMJ 2002;324:23–5. 10.1136/bmj.324.7328.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sandoval JL, Theler JM, Cullati S, et al. . Introduction of an organised programme and social inequalities in mammography screening: A 22-year population-based study in Geneva, Switzerland. Prev Med 2017;103:49–55. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sassi F, Belloni A, Mirelman AJ, et al. . Equity impacts of price policies to promote healthy behaviours. Lancet 2018;391:2059–70. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30531-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Charafeddine R, Demarest S, Van der Heyden J, et al. . Using multiple measures of inequalities to study the time trends in social inequalities in smoking. Eur J Public Health 2013;23:546–51. 10.1093/eurpub/cks083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-028971supp002.pdf (544.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-028971supp001.pdf (544.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-028971supp003.pdf (487.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-028971supp004.pdf (918.6KB, pdf)