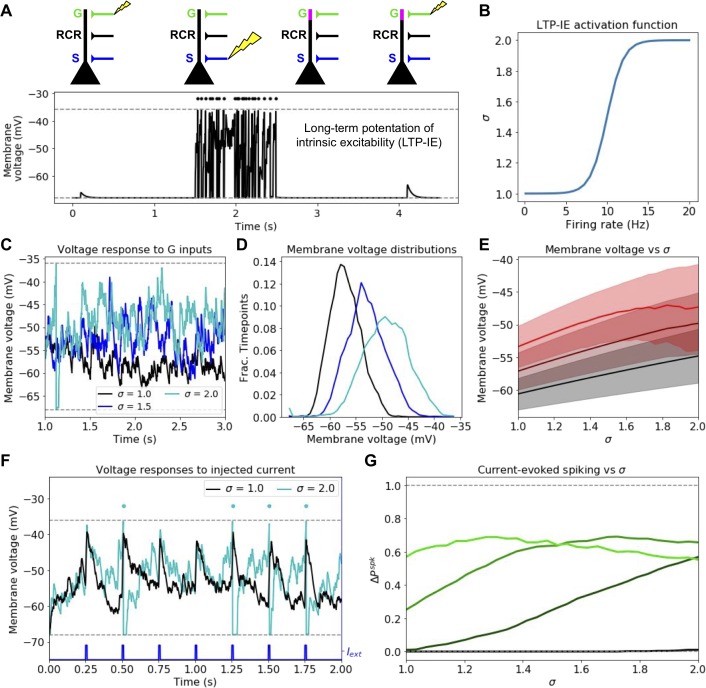

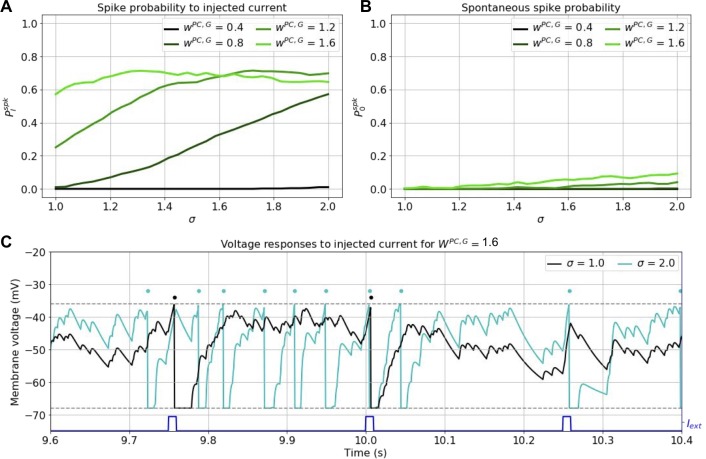

Figure 1. Mechanism and consequences of LTP-IE.

(A) Demonstration using leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) neuron model of fast activity-driven LTP-IE, which doubles membrane voltage responses to gate inputs as described in Hyun et al. (2013); Hyun et al. (2015). A spike in an upstream gate neuron (G) first elicits a small EPSP in the pyramidal cell (PC); a 1 s spike train (dots) at approximately 20 Hz is evoked by strong stimulation of sensory inputs S; when G spikes again, the EPSP has doubled in size. ‘RCR’ refers to recurrent inputs from other PCs (not used in this figure). Dashed lines show leak and spike-threshold voltages. (B) Shifted logistic function for LTP-IE strength (effective weight scaling factor) σ vs. PC firing rate over 1 s. (C) Example membrane voltages of PCs with different σ receiving stochastic but statistically identical gating input spikes. (D) Distribution of PC membrane voltage for σ values shown in C. (E) Mean (thick) and standard deviation (shading) of Vm as a function of σ for three gate firing rates. Black: rG = 75 Hz; dark red: rG = 125 Hz; red: rG = 175 Hz. (F) Example differential sensitivities of PC spike responses to injected current input (blue) for two different σ. Dashed lines show leak and spike threshold potential; dots indicate spikes (which only occur for the σ = 2 case [cyan]). (G) Difference between current-evoked spike probability and spontaneous spike probability as a function of σ for four initial gate input weights. Color code, in order of increasing lightness: wPG,G = 0.4,. 8, 1.2, 1.6 (see Materials and methods for units).