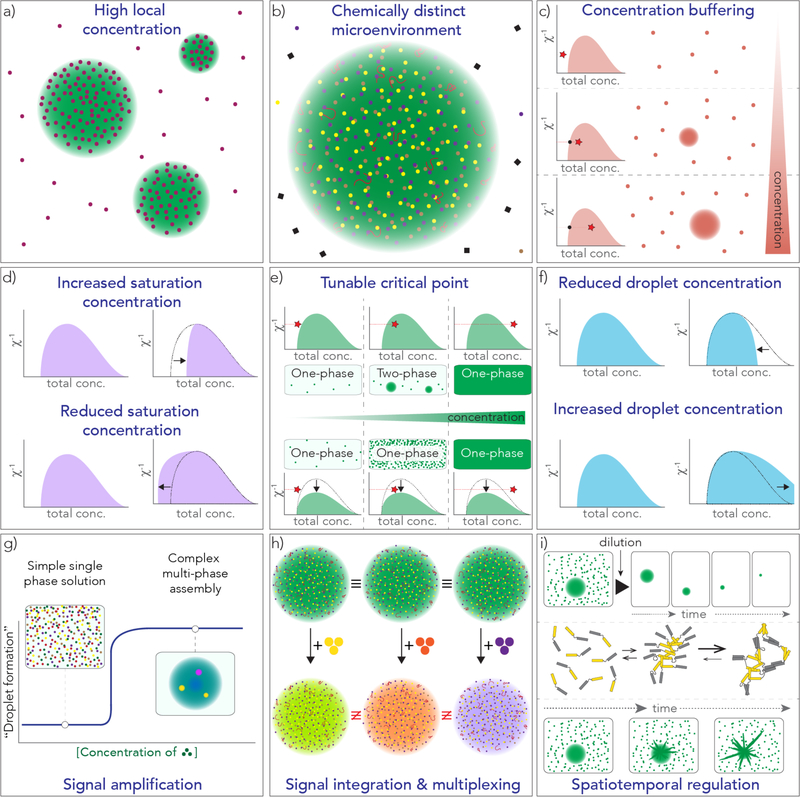

Figure 2. Summary of a subset of putative mechanistic and regulatory features that phase transitions might support.

For convenience, all phase diagrams drawn here are in the inverse χ (χ−1) versus concentration plane, but the ordinate could alternatively be one of any number of parameters such as salt concentration, pH, concentrations of binding partners etc. The parameter χ−1 provides a measure of the strength of interaction between constitutive components (high values reflect weaker interactions). These diagrams are meant to be illustrative of the types of phenomena one might expect to see. a) Condensates facilitate a high local concentration of scaffold and client components. b) Through the partitioning of distinct components, the condensate interior can provide a specific repertoire of macromolecules. c) A phase boundary provides a passive mechanism to fix the bulk concentration of scaffold components. At concentrations above the low concentration arm of the coexistence line, additional components partition into condensates, while the concentration in the soluble phase remains unchanged. In this way, the volumes of the two phases will change, but their concentrations will not. d) The low concentration arm of the coexistence curve can move right (top) or left (bottom), leading to an increase or decrease in the saturation concentration, respectively. e) The critical point can move up or down, such that for a system where the position on the ordinate was already close to the critical temperature a shifting of the critical point down could eliminate the ability to form condensates (bottom). f) The high concentration arm of the coexistence curve can move left (top) or right (bottom) indicating a decrease or an increase in the concentration of components inside the condensate, respectively. g) For multicomponent assemblies, the presence or absence of a single component can trigger the formation of an arbitrarily complex assembly with multi-phase behaviour. h) Condensates with similar components may have very different functional outputs in response to the presence of one specific component versus another. i) Condensate dissolution and disassembly dynamics may be complex and could depend on multiple different factors, leading to rates that are quite different to those predicted by simple mean-field models. A condensate could persist for long timescales even after the bulk concentration is below the saturation concentration if the droplet was kinetically trapped (top row). If the components contain multiple distinct interacting domains, once condensate formation has been driven by one set of domains, additional interactions may now occur via an orthogonal mechanism (middle row). A secondary nucleation-dependent process (such as solid formation, e.g. spherulite or amyloid growth, as depicted in the bottom row) could occur within the condensate, allowing a liquid-like droplet to transition into an alternative state according to some characteristic and sequence/composition dependent timescale.