An estimated 54.4 million (approximately one in four) U.S. adults have doctor-diagnosed arthritis (arthritis) (1). Severe joint pain and physical inactivity are common among adults with arthritis and are linked to adverse mental and physical health effects and limitations (2,3). CDC analyzed 2017 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data to estimate current state-specific prevalence of arthritis and, among adults with arthritis, the prevalences of severe joint pain and physical inactivity. In 2017, the median age-standardized state prevalence of arthritis among adults aged ≥18 years was 22.8% (range = 15.7% [District of Columbia] to 34.6% [West Virginia]) and was generally highest in Appalachia and Lower Mississippi Valley regions.* Among adults with arthritis, age-standardized, state-specific prevalences of both severe joint pain (median = 30.3%; range = 20.8% [Colorado] to 45.2% [Mississippi]) and physical inactivity (median = 33.7%; range = 23.2% [Colorado] to 44.4% [Kentucky]) were highest in southeastern states. Physical inactivity prevalence among those with severe joint pain (47.0%) was higher than that among those with moderate (31.8%) or no/mild joint pain (22.6%). Self-management strategies such as maintaining a healthy weight or being physically active can reduce arthritis pain and prevent or delay arthritis-related disability. Evidence-based physical activity and self-management education programs are available that can improve quality of life among adults with arthritis.

BRFSS is an ongoing state-based, landline and cellular telephone survey of noninstitutionalized adults in the United States aged ≥18 years that is conducted by state and territorial health departments in 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia (DC), and U.S. territories.† The combined (telephone and cellular) median response rate in 2017 among states was 45.9% (range = 30.6%–64.1%); 435,331 adults reported information about arthritis status and age, and among them, 144,099 reported having arthritis.§ Having arthritis was defined as a response of “yes” to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you have arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia?” No/mild, moderate, and severe joint pain were defined by responses of 0–3, 4–6, and 7–10, respectively, to the question “Please think about the past 30 days, keeping in mind all of your joint pain or aching and whether or not you have taken medication. On a scale of 0 to 10 where 0 is no pain or aching and 10 is pain or aching as bad as it can be, during the past 30 days, how bad was your joint pain on average?” Physical inactivity was defined as a response of “no” to the question “During the past month, other than your regular job, did you participate in any physical activities or exercises such as running, calisthenics, golf, gardening, or walking for exercise?”

All analyses, which accounted for BRFSS’s complex sampling design, were conducted using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute) and SUDAAN (version 11.0; RTI International). Sampling weights, using iterative proportional fitting (raking), were applied to make estimates representative of each state.¶ Age-standardized,** state-specific prevalences of arthritis among adults aged ≥18 years, and of severe joint pain and physical inactivity among adults with arthritis, were calculated by selected characteristics. Differences across subgroups were tested using t-tests, and orthogonal linear contrasts were conducted for tests of trends to detect linear patterns in ordinal variables (4); all differences and trends reported in the text are significant (α = 0.05).

In 2017, age-specific arthritis prevalence was higher with increasing age, ranging from 8.1% among those aged 18–44 years to 50.4% among those aged ≥65 years (Table 1). Age-standardized arthritis prevalence was significantly higher among women (25.4%) than among men (19.1%); non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Natives (29.7%) than among other racial/ethnic groups (range = 12.8%–25.5%); and those unable to work/disabled (51.3%), compared with retired (34.3%), unemployed (26.0%), or employed/self-employed (17.7%). Arthritis prevalence was higher with increasing body mass index, ranging from 17.9% among those with healthy weight or underweight to 30.4% among those with obesity. Arthritis prevalence was lower among Hispanics and non-Hispanic Asians than among other racial/ethnic groups, was inversely related to education and federal poverty level, and was higher among those living in more rural areas compared with urban dwellers.

TABLE 1. Age-specific and age-standardized* prevalence of arthritis† among U.S. adults aged ≥18 years, and among those with arthritis, prevalences of severe joint pain,§ and physical inactivity,¶ by selected characteristics — Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2017.

| Characteristic | Sample size (adults aged ≥18 yrs) | Unweighted no. with arthritis** | Arthritis, % (95% CI) | Severe joint pain,†† % (95% CI) | Physical inactivity,†† % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age group (yrs)

| |||||

| 18–44 |

122,340 |

11,615 |

8.1 (7.8–8.3) |

33.0 (31.3–34.7) |

31.0 (29.4–32.7) |

| 45–64 |

159,379 |

54,383 |

31.8 (31.3–32.3) |

35.6 (34.7–36.5) |

35.9 (35.0–36.8) |

| ≥65 |

153,612 |

78,101 |

50.4 (49.8–51.0) |

25.1 (24.3–25.9) |

37.0 (36.1–37.8) |

|

Sex

| |||||

| Men |

192,681 |

52,827 |

19.1 (18.8–19.4) |

27.3 (25.9–28.7) |

30.4 (29.1–31.7) |

| Women |

242,460 |

91,221 |

25.4 (25.0–25.7) |

36.0 (34.7–37.3) |

35.6 (34.3–36.9) |

|

Race/Hispanic ethnicity§§

| |||||

| White |

331,585 |

116,255 |

24.1 (23.8–24.3) |

27.4 (26.4–28.4) |

31.8 (30.8–32.8) |

| Black |

34,952 |

11,594 |

24.1 (23.3–24.9) |

50.9 (48.0–53.9) |

40.4 (37.3–43.5) |

| Hispanic |

32,064 |

5,800 |

16.9 (16.2–17.7) |

42.0 (38.7–45.4) |

36.0 (32.8–39.3) |

| Asian |

9,165 |

1,161 |

12.8 (11.2–14.5) |

27.7 (16.9–41.8)¶¶ |

36.1 (25.0–48.9) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native |

8,206 |

2,805 |

29.7 (27.2–32.4) |

42.0 (35.3–49.0) |

33.2 (27.7–39.1) |

| Other/Multiple race |

11,952 |

3,930 |

25.5 (24.1–27.0) |

37.4 (33.4–41.7) |

33.3 (29.1–37.7) |

|

Highest level of education

| |||||

| Less than high school graduate |

31,177 |

12,595 |

25.7 (24.9–26.6) |

54.1 (51.0–57.2) |

46.4 (43.1–49.6) |

| High school graduate or equivalent |

118,840 |

43,212 |

23.4 (23.0–23.8) |

35.5 (33.9–37.1) |

38.7 (37.0–40.3) |

| Technical school/Some college |

120,950 |

42,634 |

24.4 (23.9–24.8) |

30.2 (28.5–31.9) |

31.6 (30.1–33.2) |

| College degree or higher |

163,230 |

45,317 |

17.5 (17.1–17.8) |

15.1 (14.0–16.3) |

20.0 (18.7–21.4) |

|

Employment status

| |||||

| Employed/Self-employed |

217,384 |

44,544 |

17.7 (17.4–18.1) |

20.6 (19.5–21.8) |

29.2 (28.0–30.4) |

| Unemployed |

18,884 |

5,864 |

26.0 (24.9–27.2) |

39.9 (36.6–43.3) |

33.4 (30.4–36.7) |

| Retired |

129,618 |

64,620 |

34.3 (28.4–40.7) |

45.8 (35.0–57.1) |

31.1 (24.2–39.1) |

| Unable to work/Disabled |

31,689 |

20,443 |

51.3 (49.8–52.7) |

66.9 (64.9–68.9) |

51.2 (48.8–53.5) |

| Other |

34,662 |

7,965 |

21.1 (20.2–22.0) |

30.6 (27.3–34.2) |

29.4 (26.0–32.9) |

|

Federal poverty level***

| |||||

| ≤125% FPL |

59,064 |

23,120 |

28.6 (28.0–29.3) |

51.6 (49.6–53.6) |

42.6 (40.6–44.7) |

| >125% to ≤200% FPL |

55,134 |

22,702 |

24.7 (24.0–25.5) |

33.0 (30.5–35.5) |

36.7 (33.9–39.5) |

| >200% to ≤400% FPL |

89,104 |

32,172 |

22.4 (21.9–23.0) |

24.9 (22.6–27.3) |

31.1 (28.8–33.4) |

| >400% FPL |

117,078 |

30,457 |

18.4 (17.9–18.8) |

13.9 (12.0–16.1) |

20.7 (18.8–22.6) |

|

Sexual orientation†††

| |||||

| Straight |

185,994 |

63,300 |

22.1 (21.8–22.5) |

31.7 (30.1–33.3) |

33.4 (32.0–34.9) |

| Lesbian/Gay/Bisexual/Queer/ Questioning |

9,346 |

2,646 |

22.5 (21.1–24.0) |

40.7 (36.3–45.4) |

33.2 (29.2–37.5) |

|

Urban-rural status§§§

| |||||

| Large metro center |

68,712 |

18,857 |

19.5 (19.0–20.0) |

34.2 (31.5–37.0) |

30.7 (28.2–33.3) |

| Large fringe metro |

83,056 |

26,913 |

22.2 (21.7–22.6) |

28.6 (26.7–30.6) |

31.6 (29.7–33.6) |

| Medium metro |

90,803 |

29,572 |

23.1 (22.7–23.5) |

33.0 (31.3–34.7) |

34.0 (32.3–35.8) |

| Small metro |

60,652 |

20,685 |

24.0 (23.5–24.6) |

32.7 (30.8–34.7) |

35.0 (33.0–37.1) |

| Micropolitan |

65,752 |

23,315 |

26.3 (25.6–26.9) |

33.3 (30.9–35.7) |

37.0 (34.7–39.4) |

| Rural (noncore) |

66,356 |

24,757 |

27.7 (26.9–28.5) |

35.7 (33.2–38.3) |

38.7 (36.2–41.2) |

|

Body mass index (kg/m2)

| |||||

| Underweight/Healthy weight (<25) |

131,890 |

34,818 |

17.9 (17.5–18.2) |

29.1 (27.2–31.0) |

28.6 (27.0–30.3) |

| Overweight (25 to <30) |

145,099 |

46,441 |

20.4 (20.0–20.8) |

28.6 (26.7–30.5) |

27.8 (26.2–29.5) |

| Obese (≥30) | 125,421 | 53,342 | 30.4 (29.9–30.9) | 37.2 (35.7–38.7) | 39.3 (37.7–40.8) |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; FPL = federal poverty level.

* Except for age groups, estimates were age-standardized to the 2000 projected U.S. population aged ≥18 years using three groups (18–44, 45–64, and ≥65 years): https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/statnt/statnt20.pdf.

† Respondents were classified as having arthritis if they responded “yes” to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you have arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia?” Overall, 144,099 respondents reported arthritis.

§ Severe joint pain was defined as a response of 7–10 to “Please think about the past 30 days, keeping in mind all of your joint pain or aching and whether or not you have taken medication. On a scale of 0 to 10 where 0 is no pain or aching and 10 is pain or aching as bad as it can be, during the past 30 days, how bad was your joint pain on average?” Overall, 141,744 (98.4%) respondents with arthritis had severe joint pain data available.

¶ Physical inactivity was defined as reporting “no” to the question “During the past month, other than your regular job, did you participate in any physical activities or exercises such as running, calisthenics, golf, gardening, or walking for exercise?” Overall, 135,160 (93.8%) respondents with arthritis had physical inactivity data available.

** Categories might not sum to sample total because of missing responses for some variables.

†† Among adults aged ≥18 years with arthritis.

§§ Persons who identified as Hispanic might be of any race. Persons who identified with a racial group were all non-Hispanic.

¶¶ Estimate is potentially unreliable because the relative standard error was between 20% and 30%.

*** Federal poverty level is the ratio of total family income to federal poverty level per family size. Overall, 35,648 respondents had missing data.

††† Sexual orientation was not asked in every state. The 27 states that asked sexual orientation were California, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, Nevada, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin. A total of 1,049 respondents refused to answer.

§§§ Urban-rural status was categorized using the National Center for Health Statistics 2013 Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_166.pdf.

Among adults with arthritis, no/mild, moderate, and severe joint pain was reported by 36.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 35.7%–36.8%), 33.0% (CI = 32.4%–33.5%), and 30.8% (CI = 30.3%–31.4%) of respondents, respectively (unadjusted prevalences). Age-specific percentages for severe joint pain declined with increasing age, ranging from 33.0% among those aged 18–44 years to 25.1% among those aged ≥65 years. Age-standardized severe joint pain prevalence was ≥40% among the following groups: those unable to work/disabled (66.9%); those with less than a high school diploma (54.1%); those living at ≤125% federal poverty level (51.6%); non-Hispanic blacks (50.9%); retired persons (45.8%); Hispanics (42.0%); non-Hispanic American Indians/Alaska Natives (42.0%); and lesbian/gay/bisexual/queer/questioning (40.7%; reported by 27 states). Severe joint pain prevalence was similar across urban/rural geographic areas, ranging from 32.7%–35.7% in all areas, except for a lower prevalence (28.6%) in large fringe metro areas (Table 1).

Among adults with arthritis, age-specific physical inactivity prevalence was higher with increasing age (ranging from 31.0% among those aged 18–44 years to 37.0% among those aged ≥65 years). Age-standardized physical inactivity prevalence was ≥40% among the following groups: those unable to work/disabled (51.2%); those with less than a high school diploma (46.4%); those living at ≤125% federal poverty level (42.6%); and non-Hispanic blacks (40.4%). Physical inactivity prevalence increased with increasing rurality and with increasing joint pain levels (ranging from 22.6% among those with no/mild joint pain to 47.0% among those with severe joint pain).

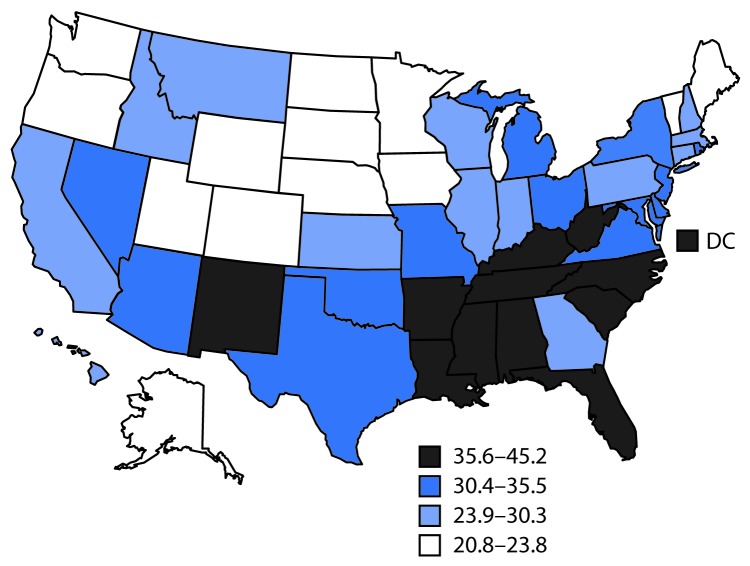

Median age-standardized state prevalence of arthritis among adults aged ≥18 years was 22.8% (range = 15.7% [DC] to 34.6% [West Virginia]) (Table 2) and was highest in Appalachia and Lower Mississippi Valley regions. Among 144,099 adults with arthritis, median age-standardized state prevalences of severe joint pain and physical inactivity were 30.3% (range = 20.8% [Colorado] to 45.2% [Mississippi]) and 33.7% (range = 23.2% [Colorado] to 44.4% [Kentucky]), respectively. Age-standardized severe joint pain (Figure) and physical inactivity prevalences were highest in southeastern states.

TABLE 2. State-specific crude and age-standardized* prevalence of arthritis† among U.S. adults aged ≥18 years and among those with arthritis, prevalences of severe joint pain,§ and physical inactivity¶ — Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2017.

| State | Arthritis |

Severe joint pain** |

Physical inactivity** |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. |

Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

No. |

Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

No. |

Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

|||||||

| Unweighted | Weighted (x 1,000) | Crude | Age-standardized | Unweighted | Weighted (x 1,000) | Crude | Age-standardized | Unweighted | Weighted (x 1,000) | Crude | Age-standardized | |

| Alabama |

2,778 |

1,241 |

33.3 (31.9–34.8) |

30.4 (29.0–31.8) |

1,050 |

477 |

38.9 (36.5–41.4) |

41.1 (37.0–45.3) |

1,158 |

519 |

44.6 (42.1–47.2) |

42.3 (38.1–46.6) |

| Alaska |

943 |

124 |

22.5 (20.4–24.8) |

22.8 (20.8–25.0) |

193 |

28 |

22.6 (18.2–27.7) |

23.8 (17.1–32.1) |

267 |

34 |

29.0 (24.2–34.3) |

29.1 (21.8–37.8) |

| Arizona |

4,925 |

1,285 |

24.3 (23.5–25.1) |

22.0 (21.3–22.8) |

1,248 |

384 |

30.3 (28.6–32.1) |

31.7 (28.6–35.0) |

1,472 |

405 |

34.5 (32.7–36.3) |

29.3 (26.4–32.4) |

| Arkansas |

2,298 |

700 |

30.9 (28.8–33.0) |

28.4 (26.3–30.5) |

734 |

260 |

37.6 (33.9–41.5) |

42.4 (35.8–49.3) |

920 |

265 |

40.6 (36.9–44.3) |

36.8 (30.8–43.2) |

| California |

2,095 |

5,873 |

19.5 (18.4–20.6) |

18.3 (17.4–19.3) |

547 |

1,682 |

28.9 (26.1–31.8) |

29.7 (24.6–35.3) |

461 |

1,432 |

26.6 (23.8–29.5) |

26.3 (21.8–31.3) |

| Colorado |

2,796 |

920 |

21.4 (20.5–22.3) |

20.3 (19.5–21.1) |

500 |

188 |

20.8 (19.0–22.8) |

20.8 (17.8–24.3) |

578 |

200 |

24.5 (22.4–26.7) |

23.2 (19.7–27.2) |

| Connecticut |

3,269 |

639 |

23.1 (22.1–24.1) |

20.1 (19.3–21.0) |

707 |

161 |

25.6 (23.5–27.9) |

28.5 (24.0–33.5) |

899 |

185 |

31.9 (29.7–34.2) |

30.5 (25.7–35.7) |

| Delaware |

1,247 |

189 |

25.3 (23.6–27.1) |

22.3 (20.7–24.0) |

381 |

62 |

33.6 (30.0–37.5) |

34.6 (28.2–41.6) |

443 |

67 |

38.5 (34.7–42.5) |

37.5 (30.6–45.0) |

| District of Columbia |

900 |

80 |

14.3 (13.2–15.5) |

15.7 (14.7–16.9) |

298 |

29 |

37.1 (33.1–41.3) |

40.4 (32.1–49.4) |

262 |

24 |

30.8 (27.1–34.8) |

29.9 (23.1–37.7) |

| Florida |

7,271 |

4,112 |

24.8 (23.6–26.0) |

20.5 (19.5–21.5) |

2,540 |

1,496 |

37.3 (34.7–40.0) |

42.0 (36.9–47.3) |

2,670 |

1,506 |

39.4 (36.7–42.1) |

34.4 (29.8–39.3) |

| Georgia |

1,826 |

1,734 |

22.3 (21.1–23.5) |

21.0 (19.9–22.1) |

606 |

562 |

32.9 (30.2–35.9) |

29.2 (25.0–33.9) |

743 |

697 |

43.7 (40.6–46.9) |

39.9 (34.8–45.2) |

| Hawaii |

1,942 |

232 |

21.0 (19.8–22.3) |

19.0 (17.9–20.1) |

411 |

51 |

22.2 (19.5–25.2) |

27.3 (22.5–32.7) |

463 |

66 |

30.1 (26.8–33.6) |

33.4 (27.8–39.6) |

| Idaho |

1,540 |

304 |

24.2 (22.7–25.7) |

22.2 (20.8–23.6) |

338 |

70 |

23.1 (20.4–26.1) |

26.1 (21.2–31.7) |

455 |

92 |

32.6 (29.3–36.0) |

30.9 (25.4–37.1) |

| Illinois |

1,726 |

2,405 |

24.5 (23.1–25.9) |

22.4 (21.2–23.7) |

388 |

633 |

26.4 (23.5–29.5) |

28.4 (22.5–35.1) |

495 |

688 |

30.5 (27.7–33.4) |

24.9 (20.5–29.9) |

| Indiana |

5,118 |

1,428 |

28.4 (27.5–29.3) |

26.1 (25.3–27.0) |

1,383 |

417 |

29.6 (28.0–31.3) |

30.3 (27.5–33.3) |

1,853 |

517 |

39.5 (37.7–41.4) |

36.9 (33.8–40.2) |

| Iowa |

2,309 |

588 |

24.6 (23.6–25.7) |

22.0 (21.0–22.9) |

434 |

123 |

21.1 (19.1–23.3) |

22.4 (18.7–26.6) |

698 |

179 |

32.7 (30.5–35.1) |

28.4 (24.6–32.4) |

| Kansas |

6,540 |

519 |

24.1 (23.4–24.7) |

22.2 (21.6–22.8) |

1,506 |

129 |

25.3 (23.9–26.7) |

26.6 (24.3–29.0) |

2,205 |

177 |

37.0 (35.4–38.5) |

34.6 (32.0–37.4) |

| Kentucky |

3,350 |

1,095 |

32.3 (30.7–33.8) |

29.4 (28.0–30.9) |

1,222 |

413 |

38.3 (35.5–41.2) |

39.2 (35.0–43.5) |

1,433 |

474 |

46.4 (43.5–49.3) |

44.4 (40.0–48.8) |

| Louisiana |

1,588 |

962 |

27.2 (25.7–28.8) |

25.5 (24.1–26.9) |

566 |

363 |

38.3 (35.2–41.5) |

39.0 (34.3–44.0) |

596 |

369 |

42.8 (39.5–46.1) |

41.7 (36.8–46.9) |

| Maine |

3,619 |

333 |

31.1 (29.8–32.5) |

26.5 (25.2–27.9) |

730 |

71 |

21.6 (19.6–23.7) |

22.2 (18.6–26.2) |

1,046 |

96 |

30.8 (28.6–33.1) |

26.4 (22.8–30.4) |

| Maryland |

4,907 |

1,146 |

24.9 (23.9–26.0) |

22.8 (21.9–23.8) |

1,140 |

304 |

26.8 (24.7–29.0) |

31.8 (27.5–36.4) |

1,520 |

367 |

35.2 (33.0–37.5) |

33.5 (29.0–38.3) |

| Massachusetts |

2,126 |

1,262 |

23.7 (22.2–25.4) |

21.3 (20.0–22.8) |

498 |

327 |

26.6 (23.3–30.1) |

25.9 (20.9–31.7) |

611 |

377 |

32.1 (28.5–35.9) |

27.9 (22.3–34.2) |

| Michigan |

3,953 |

2,338 |

30.5 (29.4–31.5) |

27.1 (26.2–28.1) |

1,079 |

749 |

32.4 (30.4–34.4) |

34.8 (31.4–38.4) |

1,217 |

781 |

35.2 (33.2–37.2) |

36.2 (32.7–39.8) |

| Minnesota |

4,269 |

833 |

19.8 (19.1–20.5) |

17.8 (17.2–18.5) |

811 |

165 |

20.2 (18.6–21.9) |

22.1 (19.3–25.2) |

1,319 |

253 |

32.7 (30.9–34.6) |

31.2 (28.0–34.6) |

| Mississippi |

1,915 |

657 |

29.3 (27.6–31.0) |

27.2 (25.6–28.8) |

709 |

272 |

42.0 (38.8–45.3) |

45.2 (39.7–50.7) |

725 |

256 |

43.1 (39.8–46.4) |

41.6 (35.9–47.6) |

| Missouri |

2,752 |

1,296 |

27.8 (26.5–29.1) |

24.9 (23.8–26.1) |

782 |

373 |

29.4 (27.0–31.9) |

30.8 (26.6–35.4) |

1,051 |

472 |

37.7 (35.1–40.3) |

35.4 (30.9–40.1) |

| Montana |

1,930 |

207 |

25.5 (24.0–26.9) |

22.6 (21.3–24.0) |

450 |

51 |

24.8 (22.1–27.8) |

27.2 (22.8–32.1) |

640 |

68 |

34.0 (31.0–37.2) |

32.2 (27.5–37.2) |

| Nebraska |

4,789 |

345 |

24.0 (23.1–25.0) |

22.0 (21.1–22.9) |

916 |

69 |

20.2 (18.4–22.1) |

22.9 (19.4–26.8) |

1,553 |

104 |

32.1 (30.1–34.2) |

29.5 (25.9–33.2) |

| Nevada |

1,112 |

462 |

20.3 (18.6–22.1) |

18.5 (17.0–20.1) |

286 |

136 |

29.8 (25.7–34.4) |

31.0 (24.4–38.5) |

322 |

150 |

33.9 (29.3–38.8) |

30.1 (23.2–38.1) |

| New Hampshire |

2,064 |

281 |

26.5 (25.1–28.1) |

23.0 (21.6–24.4) |

447 |

62 |

22.3 (19.9–24.9) |

24.7 (19.6–30.7) |

584 |

80 |

31.0 (28.2–34.1) |

33.7 (27.2–40.9) |

| New Jersey |

3,751 |

1,576 |

22.9 (21.8–24.1) |

20.4 (19.4–21.4) |

1,089 |

485 |

31.2 (28.6–33.9) |

34.0 (29.0–39.4) |

1,308 |

585 |

39.9 (37.1–42.7) |

36.1 (31.0–41.5) |

| New Mexico |

2,099 |

398 |

25.3 (24.0–26.8) |

23.0 (21.7–24.4) |

631 |

136 |

34.3 (31.3–37.5) |

38.7 (33.4–44.2) |

616 |

111 |

30.2 (27.4–33.1) |

25.6 (21.9–29.8) |

| New York |

3,509 |

3,445 |

22.6 (21.6–23.6) |

20.4 (19.6–21.2) |

976 |

1,083 |

32.0 (29.7–34.4) |

32.8 (28.9–37.1) |

1,086 |

1,085 |

34.8 (32.5–37.3) |

33.3 (29.2–37.7) |

| North Carolina |

1,477 |

1,921 |

24.4 (23.0–26.0) |

22.1 (20.8–23.5) |

517 |

695 |

36.9 (33.6–40.4) |

43.6 (38.2–49.2) |

524 |

663 |

36.0 (32.7–39.5) |

36.4 (30.8–42.3) |

| North Dakota |

2,307 |

141 |

24.3 (23.1–25.6) |

23.3 (22.1–24.5) |

378 |

27 |

19.3 (17.0–21.7) |

21.7 (17.7–26.2) |

749 |

46 |

35.0 (32.3–37.9) |

35.9 (31.1–41.0) |

| Ohio |

4,741 |

2,598 |

29.1 (28.0–30.2) |

25.9 (24.9–27.0) |

1,291 |

760 |

29.6 (27.5–31.7) |

32.4 (28.7–36.4) |

1,804 |

936 |

38.1 (36.0–40.3) |

34.0 (30.3–37.8) |

| Oklahoma |

2,423 |

814 |

27.8 (26.5–29.1) |

26.0 (24.8–27.2) |

667 |

257 |

32.4 (30.0–35.0) |

32.9 (28.8–37.2) |

947 |

314 |

41.4 (38.8–44.0) |

37.4 (33.3–41.8) |

| Oregon |

1,650 |

847 |

26.6 (25.2–28.0) |

23.9 (22.7–25.2) |

342 |

193 |

23.3 (20.8–25.9) |

23.7 (19.8–28.1) |

443 |

236 |

30.1 (27.3–33.0) |

27.0 (22.9–31.5) |

| Pennsylvania |

2,128 |

2,915 |

29.2 (27.8–30.6) |

25.4 (24.2–26.7) |

556 |

789 |

27.4 (24.9–30.0) |

28.9 (24.9–33.4) |

658 |

956 |

34.9 (32.1–37.8) |

35.2 (30.3–40.4) |

| Rhode Island |

1,968 |

229 |

27.4 (25.9–29.0) |

24.7 (23.2–26.1) |

508 |

64 |

28.1 (25.3–31.1) |

33.2 (27.4–39.6) |

616 |

74 |

35.1 (32.1–38.1) |

34.0 (28.2–40.4) |

| South Carolina |

4,286 |

1,082 |

28.0 (26.9–29.1) |

24.9 (23.9–25.8) |

1,340 |

371 |

34.9 (32.8–37.0) |

38.5 (34.4–42.7) |

1,445 |

362 |

36.1 (34.0–38.2) |

35.5 (31.4–39.7) |

| South Dakota |

2,077 |

145 |

22.2 (20.6–23.9) |

20.0 (18.5–21.6) |

468 |

32 |

22.6 (19.5–26.1) |

22.4 (17.6–28.1) |

621 |

46 |

33.0 (29.2–37.0) |

28.6 (22.7–35.3) |

| Tennessee |

2,107 |

1,540 |

30.1 (28.6–31.7) |

27.4 (26.0–28.8) |

710 |

547 |

36.1 (33.2–39.0) |

36.7 (32.1–41.5) |

799 |

562 |

40.5 (37.5–43.5) |

37.0 (32.7–41.5) |

| Texas |

3,818 |

4,438 |

21.3 (19.9–22.9) |

20.8 (19.5–22.3) |

1,127 |

1,572 |

36.0 (32.1–40.1) |

35.5 (29.1–42.4) |

1,474 |

1,697 |

41.8 (37.6–46.0) |

38.7 (32.2–45.6) |

| Utah |

2,512 |

414 |

19.3 (18.4–20.2) |

20.2 (19.4–21.1) |

531 |

89 |

22.0 (19.9–24.2) |

22.4 (19.4–25.7) |

695 |

110 |

27.6 (25.4–30.0) |

25.9 (22.6–29.5) |

| Vermont |

2,184 |

138 |

27.7 (26.4–29.1) |

23.7 (22.6–24.9) |

430 |

30 |

22.2 (19.9–24.6) |

22.5 (18.6–26.9) |

538 |

36 |

28.3 (25.8–31.0) |

27.0 (22.5–31.9) |

| Virginia |

3,184 |

1,628 |

25.1 (24.0–26.2) |

23.1 (22.2–24.1) |

835 |

481 |

29.9 (27.7–32.3) |

30.7 (26.9–34.9) |

1,064 |

567 |

36.6 (34.3–39.1) |

36.6 (32.4–41.0) |

| Washington |

4,154 |

1,359 |

24.1 (23.2–25.0) |

22.3 (21.5–23.2) |

808 |

294 |

21.9 (20.2–23.8) |

22.1 (19.3–25.1) |

1,002 |

327 |

25.5 (23.8–27.4) |

23.7 (20.9–26.8) |

| West Virginia |

2,501 |

561 |

39.2 (37.7–40.8) |

34.6 (33.1–36.0) |

856 |

206 |

37.3 (35.0–39.6) |

37.5 (33.7–41.4) |

996 |

226 |

41.4 (39.1–43.8) |

39.0 (35.1–43.0) |

| Wisconsin |

1,856 |

1,136 |

25.6 (24.2–27.1) |

22.9 (21.6–24.2) |

463 |

294 |

26.1 (23.4–29.0) |

26.9 (22.5–31.8) |

493 |

293 |

27.9 (24.9–31.0) |

26.2 (21.2–31.9) |

| Wyoming |

1,470 |

113 |

25.4 (23.9–26.9) |

23.4 (22.1–24.8) |

290 |

26 |

23.2 (20.4–26.1) |

23.6 (19.1–28.9) |

499 |

40 |

36.4 (33.2–39.6) |

35.4 (30.2–41.1) |

| State median | N/A | N/A | 24.9 | 22.8 | N/A | N/A | 28.9 | 30.3 | N/A | N/A | 34.9 | 33.7 |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; N/A = not applicable.

* Estimates were age-standardized to the 2000 projected U.S. population aged ≥18 years using three groups (18–44, 45–64, and ≥65 years).

† Respondents were classified as having arthritis if they responded “yes” to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you have arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia?”

§ Severe joint pain was defined as a response of 7–10 to “Please think about the past 30 days, keeping in mind all of your joint pain or aching and whether or not you have taken medication. On a scale of 0 to 10 where 0 is no pain or aching and 10 is pain or aching as bad as it can be, during the past 30 days, how bad was your joint pain on average?”

¶ Physical inactivity was defined as reporting “no” to the question “During the past month, other than your regular job, did you participate in any physical activities or exercises such as running, calisthenics, golf, gardening, or walking for exercise?”

** Among adults aged ≥18 years with arthritis.

FIGURE.

Age-standardized,* state-specific percentage of severe joint pain† among U.S. adults aged ≥18 years with arthritis§ — Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2017

* Estimates were age-standardized to the 2000 projected U.S. population aged ≥18 years using three age groups (18–44, 45–64, and ≥65 years).

† Severe joint pain was defined as a response of 7–10 to “Please think about the past 30 days, keeping in mind all of your joint pain or aching and whether or not you have taken medication. On a scale of 0 to 10 where 0 is no pain or aching and 10 is pain or aching as bad as it can be, during the past 30 days, how bad was your joint pain on average?”

§ Respondents were classified as having arthritis if they responded “yes” to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you have arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia?”

Discussion

The 2017 age-standardized prevalence of arthritis was highest in Appalachia and the Lower Mississippi Valley; prevalences of severe joint pain and physical inactivity among adults with arthritis were highest in southeastern states. Estimates for all three outcomes in 2017 were similar to those in 2015 (5). Except for age, urban-rural status, and sexual orientation, sociodemographic patterns for prevalences of severe joint pain and physical inactivity were similar and offer potential targets for interventions designed to reduce arthritis pain.

Joint pain is often managed with medications, which are associated with various adverse effects. The 2016 National Pain Strategy advises that pain-management strategies be multifaceted and individualized and include nonpharmacologic strategies,†† and the American College of Rheumatology recommends regular physical activity as a nonpharmacologic pain reliever for arthritis.§§ Although persons with arthritis report that pain, or fear of causing or worsening it, is a substantial barrier to exercising (6), physical activity is an inexpensive intervention that can reduce pain, prevent or delay disability and limitations, and improve mental health, physical functioning, and quality of life with few adverse effects (7,8).¶¶ Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommends that adults, including those with arthritis, engage in the equivalent of at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity per week for substantial health benefits.*** Adults who are unable to meet the aerobic guideline because of their condition (e.g., those with severe joint pain) should engage in regular physical activity according to their abilities and avoid physical inactivity. Even small amounts of physical activity can improve physical functioning in adults with joint conditions (9). Most adults with arthritis pain can safely begin walking, swimming, or cycling to increase physical activity.

Arthritis-appropriate, evidence-based, self-management programs and low-impact, group aerobic, or multicomponent physical activity programs are designed to safely increase physical activity in persons with arthritis.†††,§§§ These programs are available nationwide and are especially important for those populations that might have limited access to health care, medications, and surgical interventions (e.g., those in rural areas, those with lower income, and racial/ethnic minorities). Physical activity programs including low-impact aquatic exercises (e.g., Arthritis Foundation Aquatic Program) and strength training (e.g., Fit and Strong!) can help increase strength and endurance. Participating in self-management education programs, such as the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program, although not physical activity–focused, is also beneficial for arthritis management and results in increased physical activity. Benefits of the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program include increased frequency of aerobic and stretching/strengthening exercise, improved self-efficacy for arthritis pain management, and improved mood (10). Adults with arthritis can also engage in routine physical activity through group aerobic exercise classes (e.g., Walk with Ease, EnhanceFitness, Arthritis Foundation Exercise Program, and Active Living Every Day).

The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, BRFSS data are self-reported and susceptible to recall, social desirability, and related biases. Second, low response rates for individual states might bias findings. Finally, institutional populations are excluded from sampling, meaning prevalences of studied outcomes are likely underestimated. Strengths include a measurement of joint pain and large sample size that allows analysis of detailed characteristics and subgroups.

Effective, inexpensive physical activity and self-management education programs are available nationwide and can help adults with arthritis be safely and confidently physically active. This report provides the most current state-specific and demographic data for arthritis, severe joint pain, and physical inactivity. These data can extend collaborations among CDC, state health departments, and community organizations to increase access to and use of arthritis-appropriate, evidence-based interventions to help participants reduce joint pain and improve physical function and quality of life.¶¶¶

Summary.

What is already known about this topic?

Approximately one in four U.S. adults has arthritis. Severe joint pain and physical inactivity are common among adults with arthritis and are linked to poor mental and physical health outcomes.

What is added by this report?

In 2017, marked state-specific variations in prevalences of arthritis, severe joint pain, and physical inactivity were observed. Physical inactivity was more prevalent among persons with severe joint pain than among those with less pain.

What are the implications for public health practice?

State-specific data support efforts to promote participation in arthritis-appropriate, evidence-based self-management education and physical activity programs, which can reduce pain, increase physical activity and function, and improve mood and quality of life.

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Appalachia region: all of West Virginia; parts of Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Virginia (https://www.arc.gov/appalachian_region/MapofAppalachia.asp). Lower Mississippi Valley region: Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee (https://www.mvd.usace.army.mil/Media/Publications/Our-Mississippi/About/Lower-Mississippi/).

Estimates were age-standardized to the 2000 projected U.S. population aged ≥18 years using three age groups: 18–44, 45–64, and ≥65 years. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/statnt/statnt20.pdf.

References

- 1.Barbour KE, Helmick CG, Boring M, Brady TJ. Vital signs: prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation—United States, 2013–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:246–53. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6609e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbour KE, Boring M, Helmick CG, Murphy LB, Qin J. Prevalence of severe joint pain among adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis—United States, 2002–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:1052–6. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6539a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy LB, Hootman JM, Boring MA, et al. Leisure time physical activity among U.S. adults with arthritis, 2008–2015. Am J Prev Med 2017;53:345–54. 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN language manual, release 11. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbour KE, Moss S, Croft JB, et al. Geographic variations in arthritis prevalence, health-related characteristics, and management—United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ 2018;67(No. SS-4) 10.15585/mmwr.ss6704a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilcox S, Der Ananian C, Abbott J, et al. Perceived exercise barriers, enablers, and benefits among exercising and nonexercising adults with arthritis: results from a qualitative study. Arthritis Rheum 2006;55:616–27. 10.1002/art.22098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelley GA, Kelley KS, Hootman JM, Jones DL. Effects of community-deliverable exercise on pain and physical function in adults with arthritis and other rheumatic diseases: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:79–93. 10.1002/acr.20347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knapen J, Vancampfort D, Moriën Y, Marchal Y. Exercise therapy improves both mental and physical health in patients with major depression. Disabil Rehabil 2015;37:1490–5. 10.3109/09638288.2014.972579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunlop DD, Song J, Lee J, et al. Physical activity minimum threshold predicting improved function in adults with lower-extremity symptoms. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017;69:475–83. 10.1002/acr.23181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brady TJ, Murphy L, O’Colmain BJ, et al. A meta-analysis of health status, health behaviors, and health care utilization outcomes of the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program. Prev Chronic Dis 2013.http://https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2013/12_0112.htm [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]