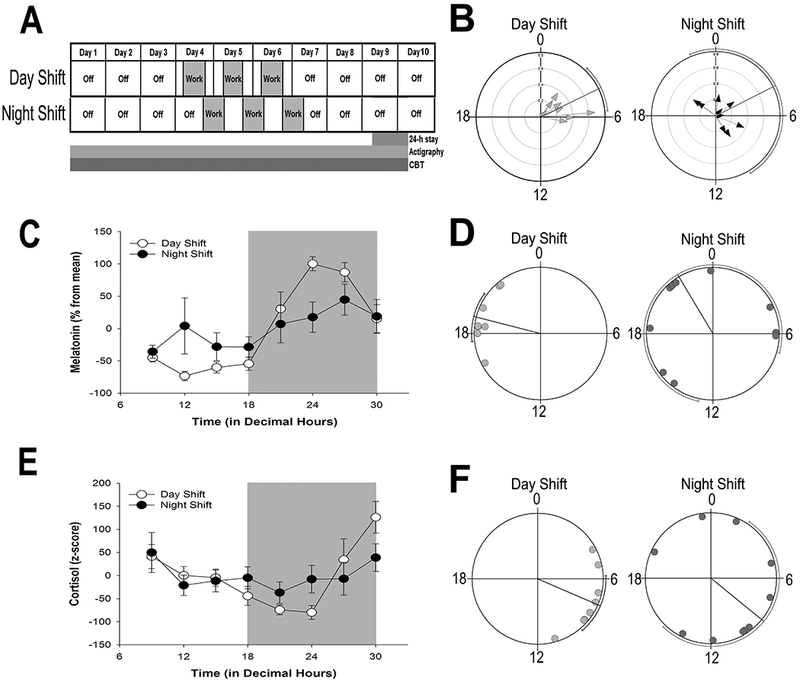

Figure 1.

Shift work schedule, and rhythmic indicators of the central circadian clock

(A) Shift work schedule of UAB nurses enrolled in the study. Ambulatory activity and sleep from actigraphy and CBT were monitored continuously for 10 days. The shift cycle (indicated in gray) consisted of three, consecutive 12-h shifts. On the last study day 9, participants spent 24-h in the UAB Clinical Research Unit (CRU) for continuous blood draws. (B) Phase clustering of CBT minimum on day 9 for individual day-shift (left) and night-shift (right) nurses plotted against time (in decimal hours). Hourly averages of CBT for individual nurses are shown in Figure S2. (C, E) Average (± SEM) normalized melatonin (C) and cortisol (E) rhythms on study day 9 in day-shift (open circles) and night-shift (closed circles) nurses across time of day (in decimal hours). (D, F) Phase clustering of dim light melatonin onset (DLMO; panel D) and peak cortisol (F) for day-shift (light gray circles) and night-shift (dark gray circles) nurses. Rayleigh test confidence intervals are indicated by lines paralleling circle circumference where clustering of both DLMO and cortisol peak for day-shift nurses indicated statistical significance (P < 0.001) while confidence intervals for night shift nurses were not significant (P > 0.05) for either cortisol or DLMO.