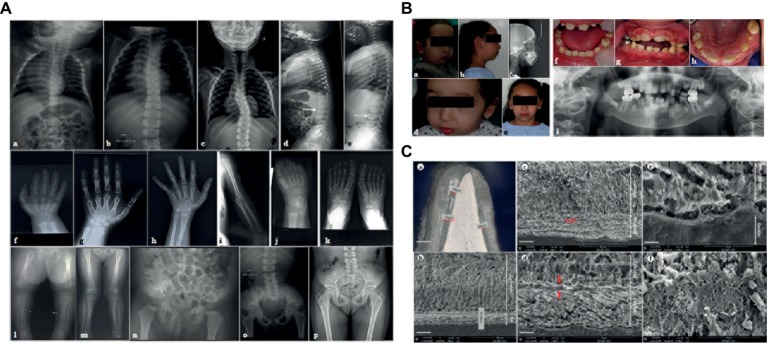

Figure 1.

(A) X-ray images of the skeletal anomalies at 3 months old (a,d,f,j,l,n), 4 years old (b,e,g,i,k,m,o) and 9 years old (c,h,p). Radiographs of the vertebral column showed the progressive scoliosis (a–c) and the ballooning of the vertebrae (d,e). Radiographs of hands and feet (f–h,j,k) displayed a progressive carpal and tarsal ossification. The patient also presented with short long bones (i,l,m), a genu valgus (l), and a horizontal acetabulum (n–p). (B) Clinical and radiological images of the facial and dental anomalies at 2 years old (a,d,f) and 9 years old (b,c,e,g–i). AI is visible in the clinical intraoral photographs affecting both the primary (f) and permanent dentition (g,h). The panoramic radiograph showed no radio-opacity contrast between dentine and enamel (i). (C) Optical numeric microscope and scanning electronic microscopy (SEM) of primary teeth. Numeric optical view of a sagittal section of a primary tooth. Dentine appears brighter than enamel. Lower central primary incisor (a). SEM micrograph of the thin enamel layer covering the vestibular side of the tooth. A thick layer of calcified calculus is present (b). Higher magnification of the thin enamel layer. Pseudo-prismatic structures are evident (arrows) (c). Micrograph of the thin enamel showing an outer aprismatic layer (between red arrows) exhibiting incremental lines (white arrow) (d). Enamel-dentinal junction showing typical scallops and unusual non-mineralized collagen fibers at the interface (e). Higher magnification of the calculus material capping the tooth. Many entangled calcified filamentous bacteria are observed (f).