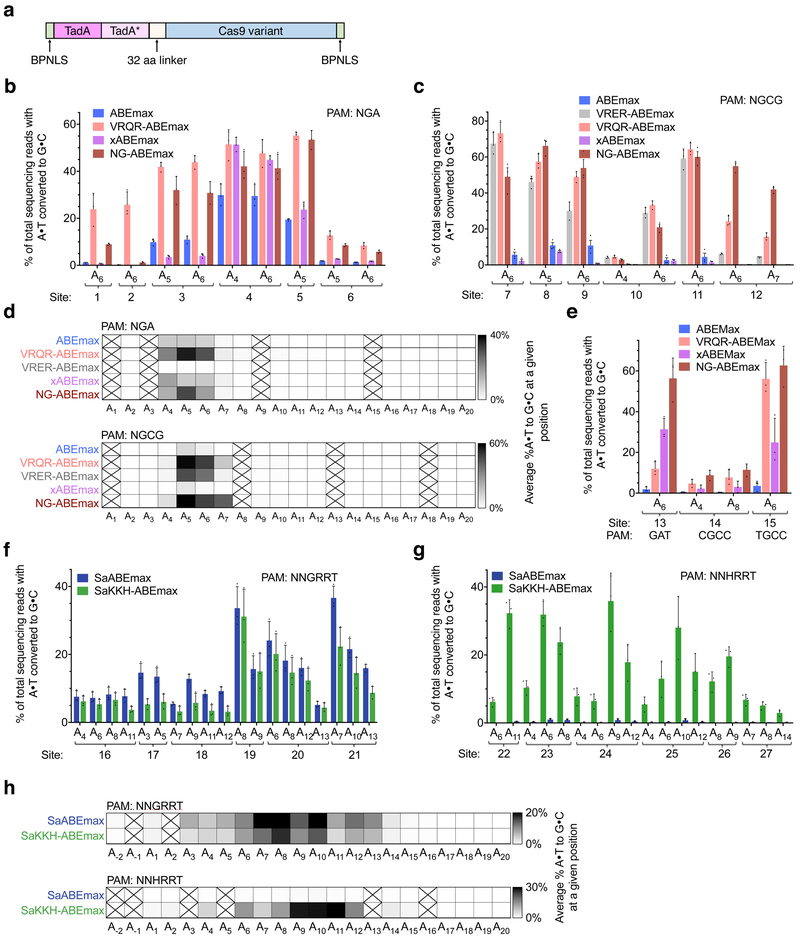

Figure 1. Cas9 PAM-variant ABE orthologues mediate A•T-to-G•C conversion in human cells.

(a) Optimized ABEmax architecture23 used for PAM variant construction. (b) Base editing in HEK293T cells by ABEmax, VRQR-ABEmax, xABEmax, and NG-ABEmax at six genomic sites containing an NGA PAM. (c) Base editing in HEK293T cells by ABEmax, VRER-ABEmax, VRQR-ABEmax, xABEmax, and NG-ABEmax at six genomic sites containing an NGCG PAM. (d) Heat maps showing average editing efficiency by SpCas9-derived ABE variants at each protospacer position across sites containing each PAM listed (n = 6). Spaces crossed out indicate a position for which no target base was present among all the genomic sites tested. (e) Base editing in HEK293T cells by ABEmax, VRQR-ABEmax, xABEmax, and NG-ABEmax at three genomic sites (PAMs: GAT, CGCC, TGCC). (f) Base editing in HEK293T cells by SaABEmax and SaKKH-ABEmax at six genomic sites containing an NNGRRT PAM. (g) Base editing in HEK293T cells by SaABEmax and SaKKH-ABEmax at six genomic sites containing an NNHRRT PAM. (h) Heat maps showing average editing efficiency by SaCas9-derived ABE variants at each protospacer position across sites containing each PAM listed (n = 6). Subscripted numbers indicate protospacer positions, counting the first base of the PAM as position 21. Values and error bars reflect the mean±s.d. of three independent biological replicates performed by different researchers on different days.