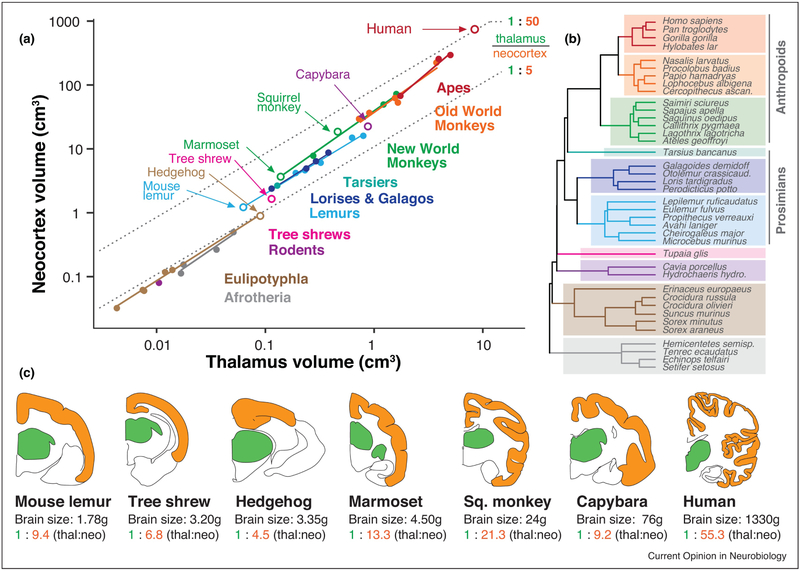

Figure 1. Primate “neocorticalization” relative to the dorsal thalamus.

Across a wide range of brain sizes, primates exhibit larger neocortices relative to the size of the dorsal thalamus than many mammalian groups. (A) Neocortex volume is plotted against dorsal thalamus volume in log-log coordinates, demonstrating effects of both concerted and mosaic evolution. Concerted evolution is demonstrated by each group having a slope greater than 1 (i.e. more than isometric scaling, or constant proportions across size variation). Mosaic evolution is exemplified by intercept shifts between mammalian lineages. Open circles indicate species shown in coronal section below. (B) A phylogenetic tree of included species, with colors corresponding to mammalian clades in (A). Even after correcting for phylogenetic relatedness, the neocortex always gets larger “faster” than the thalamus does (see text). (C) Coronal sections of selected brains in the dataset above, taken from a similar rostrocaudal level (ventral posterior [VP] nucleus of the thalamus), with associated brain sizes and thalamus:neocortex proportions. Primates, and particularly anthropoids (monkeys and apes) have an unusually large neocortex volume that dwarfs size-associated concerted effects. This mosaic evolution of the primate neocortex is so extreme (over & above size-related concerted effects) that only the largest rodent brain (capybara) has similar thalamus-to-neocortex proportions as the smallest primate brain (mouse lemur). Data from [15,22]. Coronal section outlines (dorsal thalamus in green, neocortex in orange) are from the Comparative Mammalian Brain Collection from the University of Wisconsin, and are not to scale. Thal = dorsal thalamus; neo = neocortex. Marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) thalamus size was estimated from the dataset in [15].