Abstract

Introduction:

Defects in tissue repair or wound healing pose a clinical, economic and social problem worldwide. Despite decades of studies, there have been few effective therapeutic treatments.

Areas covered:

We discuss the possible reasons for why growth factor therapy did not succeed. We point out the lack of human disorder-relevant animal models as another blockade for therapeutic development. We summarize the recent discovery of secreted heat shock protein-90 (Hsp90) as a novel wound healing agent.

Expert commentary:

Wound healing is a highly complex and multistep process that requires participations of many cell types, extracellular matrices and soluble molecules to work together in a spatial and temporal fashion within the wound microenvironment. The time that wounds remain open directly correlates with the clinical mortality associated with wounds. This time urgency makes the healing process impossible to regenerate back to the unwounded stage, rather forces it to take many shortcuts in order to protect life. Therefore, for therapeutic purpose, it is crucial to identify so-called “driver genes” for the life-saving phase of wound closure. Keratinocyte-secreted Hsp90α was discovered in 2007 and has shown the promise by overcoming several key hurdles that have blocked the effectiveness of growth factors during wound healing.

Keywords: Wound healing, Driver genes, Growth factors, Heat shock proteins, Therapeutics

1. Introduction

Wound healing is often referred to the repair of damaged epidermal and dermal tissues in skin, the largest organ in mammals. Mechanistically, it is similar to the repair of injured tissues of internal organs. Due to its experimentally convenient location, skin wound healing is among the most frequently used experimental models to gain insights into mechanisms of the repair process. Skin wound healing is histologically divided into 1) hemostasis phase, 2) inflammatory phase, 3) proliferation phase and 4) maturation/remodeling phase [1, 2]. The hemostasis and inflammatory phases occur immediately following the injury and last 7 to 10 days. During this period of time, the signs of inflammation, such as erythema, heat, oedema, pain and functional disturbance, are experienced. The two predominant cell types at work in these phases are the neutrophils and macrophages that constitute the host immune response to the injury. The proliferation phase refers to the period of three to four weeks following the hemostasis and inflammation phases. During this phase, the granulation tissue, comprised of extracellular matrices and newly formed blood vessels, is generated and used as the pavement support for the epidermal cells at the wound edge to attach and migrate upon - a process known as re-epithelialization. Finally, the maturation phase that involves collagen remodeling, angiogenesis and cell apoptosis could take many months (12–15 months) to complete. The spatial-temporal relationship of these distinct and yet overlapping phases of wound healing is schematically depicted in Figure 1 by images of real mouse and pig skin wound healing. It emphasizes the two clinical milestones, wound closure and functionality of the healed wound, and the dramatic difference in time to complete them. Although the mouse wound on day 10 and pig wound on day 19, as shown in Figure 1, were closed, the underneath remodeling processes have just begun to ultimately achieve the similar elasticity and thickness as the surrounding unwounded skin. Therefore, a newly re-epithelialized wound is intuitively like a newly built house with only a completed roof, but internal structures, such as floor, walls, kitchen and bathroom, all remain to be built. Due to limitations of the available animal models, most previous studies have focused on the inflammation and proliferation phases of wound healing, leading to the point of wound closure. Therefore, wound therapeutic development have focused more on the “driver genes” during the wound closure phase, but less on the maturation and remodeling phase. For example, wound closure is achieved by inner migrating keratinocyte-led re-epithelialization around edge of the wound. Those factors that are responsible for driving keratinocyte migration under the wound microenvironmental conditions are the primary sought-after targets for therapeutics. Due to space restriction by this journal, this review will entirely focus on the recent finding that the secreted form of heat shock protein-90alpha (Hsp90α) is such a driver gene during wound healing. For studies of other HSP family members in wound healing, the authors recommend several previously published comprehensive and excellent reviews [3, 4, 5, 6].

Figure 1. The special-temporal relationship between wound closure and wound maturation.

Typical full thickness wounds were created in mice or pigs, as indicated. For healthy humans, wound closure completes within 2–3 weeks, whereas wound maturation could take over one year. Delayed wound closure can result from many chronic illnesses. Wound closure is the primary focus of therapeutic development in wound healing.

2. The conventional wisdom

Due to natural selection and survival of the current species, most human beings are well programmed to heal skin wounds. Nevertheless, even today chronic skin wounds, including the three major types of venous stasis, pressure (bedsores) and diabetic foot ulcers, represent a challenging clinical conundrum due to paucity of effective treatments. The discovery of the first growth factor, the epidermal growth factor (EGF) in particular, in the late 70s generated a great deal of hope and soon has become the conventional wisdom that locally released growth factors in injured tissues constitute the main driving force to promote wound healing. Over the past several decades, growth factors are regarded as the “wound healing factors” that are responsible for promoting the lateral migration of epidermal keratinocytes to close the wound, attracting the inward migration of dermal fibroblasts to remodel the damaged tissue and recruiting the microvascular endothelial cells to re-build vascularized neodermis in the wounded space [6, 7, 8. 9]. Table 1 summarizes the reported growth factors whose ELISA-detected levels elevate from unwounded skin (i.e. in plasma) to wounded skin (i.e. in serum). The growth factors whose concentrations elevated from the plasma (unwounded tissue) to serum (injured tissue) transition (in bold numbers) were regarded as the potential drivers of wound closure. Since the first report of EGF clinical trial on wound healing in 1989 [10], more than a dozen of growth factor trials on wound healing have been conducted, alone or in combinations. The partial list includes 1) EGF on partial thickness wounds of skin grafts [10], on traumatic corneal epithelial defects [11], on tympanic membrane with chronic perforation [12] and on advanced diabetic foot ulcers [13, 14]; 2) basic FGF (bFGF) on partial-thickness burn wounds of children [15], on second degree burns [16] and on diabetic ulcers [17]; 3) acidic FGF (aFGF) on partial thickness burns and skin graft donor sites [18]; 4) GM-CSF plus bFGF on pressure ulcers [19]; and 5) PDGF-BB on chronic pressure and diabetic ulcers [20–25]. Additional ongoing trials with new growth factors are likely missing from this list. Despite reportedly promising clinical efficacies in humans from most of these double-blinded clinical trials, only the human recombinant PDGF-BB has advanced to receive the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for treatment of limb diabetic ulcers (RegranexTM/becaplermin gel 0.01%, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Raritan, NJ). Following its approval in 1997, however, the reports of multicenter, randomized, parallel tests in human patients showed that becaplermin gel at 100 μg PDGF-BB/g vesicle improved an overall 15% in wound closure (50% treated versus 36% placebo) [22, 24, 25]. Generally, these results are not considered as cost-effectively beneficiary for clinical practice [26, 27]. In 2008, the US FDA added a “black box” warning label to becaplermin gel for increased risks of cancer mortality in patients who need extensive treatments (≥ 3 tubes). This reported side-effect may not be surprising to growth factor researchers on cancer, since (even before FDA approval of the becaplermin gel for clinical use) it has been clearly demonstrated that overexpression of PDGF-BB (c-sis gene) or autocrine of its viral form, v-sis, at as low as 15–30 ng/ml could cause cell transformation [28]. In comparison, the clinically recommended dosage of PDGF-BB in becaplermin gel is hundreds fold higher than the physiological range of PDGF-BB levels in human circulation [29].

Table 1.

Reported growth factor levels in human plasma and human serum.*

| Growth factor | Human plasma (ng/ml) | Human serum (ng/ml) | Target cell(s) | Source of info. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bFGF | UD | UD | Fibroblast | bFGF Qt, R & D |

| IL-1α | UD | UD | Fibroblast | IL-1α Qt, R & D |

| KGF | 0.09 | 0.09 | Keratinocyte | KGF Qt, R & D |

| Insulin | 0.2 ~ 1.08 | 0.2 ~ 1.08 | All | ARUP Lab. |

| HGF | 0.787 | 1.257 | Keratinocyte | HGF Qt, R & D |

| IGF-1 | 86 | 105 | All | IGF-1 Qt, R & D |

| TGFβ1 | 0 ~ 1.26 | 40.6 | Fibroblast | TGFβ1 Qt, R & D |

| TGFβ2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | Fibro. & endo | TGFβ2 Qt, R & D |

| TGFβ3 | UD | 0.15–0.2 | Fibro. & endo | Hering et al. 2001 |

| TGFα | UD | UD to 0.032 | Keratinocyte | TGFα Qt, R & D |

| EGF | 0.013 | 0.336 | Kera. & fibro. | EGF Qt, R & D |

| HB-EGF | ND | ND | Keratinocyte | none |

| IL-8 | 0.004 | 0.012 | Keratinocyte | IL-8 Qt, R & D |

| PDGF-BB | 0.05 | 3.4 | Fibroblast | PDGF-bb Qt, R & D |

| VEGF | 0.05 | 0.4 | Endothelial | VEGF Qt, R & D |

Numbers in bold are significantly higher in serum than plasma. ND = no data; Qt = Quantikine kits; R&D = R&D Systems, Inc.; UD = undetectable; VEGF = Vascular endothelial growth factor.

3. Natural hurdles against growth factors in wound healing

We decided to use PDGF-BB in vitro and FDA-approved becaplermin gel in vivo as an example to investigate what was against the effectiveness of growth factor therapy in wound healing. We postulated that understanding the limitations of growth factors help to identify new classes “driver genes” and development of more effective and safer wound healing treatments. We identified three intrinsic deficiencies for PDGF-BB in treatment of skin wounds, which could also apply to other growth factors. First, wound healing requires the coordinated cell migration and proliferation of at least the three main types of skin cells within the wound - epidermal keratinocytes, dermal fibroblasts and microvascular endothelial cells. These cells are linked to distinct biological processes required for the healing process: re-epithelialization (by keratinocytes), fibroplasia (by fibroblasts) and neoangiogenesis (by endothelial cells). Therefore, an effective therapeutic should be able to affect all these cells and recruit them into the wound. However, among the three cell types, PDGF-BB only engages the dermal fibroblasts, because dermal fibroblasts are the only cell type that express the receptor for PDGF-BB, PDGFR (α and β), a receptor tyrosine kinase that is essential for a cell to receive and respond to PDGF-BB. There is complete lack of the PDGFR in keratinocytes and endothelial cells [30]. Therefore, becaplermin gel does not promote re-epithelialization, the most critical process to close the wound, and does not increase neovascularization (new blood vessel formation) that supplies nutrients and oxygen to the wound bed. Second, even for dermal fibroblasts, the pro-motility and pro-proliferation functions of PDGF-BB can be nullified by the transforming growth factor-beta (TGFβ) family cytokines, especially TGFβ3, which is abundantly present in the wound environment [30]. The wound bed is rich in TGFβ due to non-closing, chronic infection and inflammatory status. Nonetheless, the mechanism of TGFβ’s anti-proliferation and anti-migration remain poorly understood [31]. This important finding provides a possible explanation for why PDGF-BB needs to be applied to the DFU (diabetic foot ulcer) daily at the concentration (~100 μg/ml), hundreds fold higher than what is available de novo from the blood circulation (0–15ng/ml), in order to override the TGFβ’s inhibition in the wound bed. As previously mentioned, PDGF-BB is among the strongest mitogens in human body and its autocrine can cause glioma in brain. This pro-cancer effect of PDGF-BB explains the potential cancer-causing risks of becaplermin gel in DFU patients. Third, functions of PDGF-BB are significantly compromised under hyperglycemia, the hallmark of diabetes. O’Brien and colleagues showed that PDGF-BB-stimulated human dermal fibroblast migration is dramatically reduced under a high glucose medium equivalent to hyperglycemia in diabetic humans[32]. While the mechanism of inhibition remains speculative, sensitivity of PDGF-BB, PDGFR, as well as the intracellular PDGF-BB signaling pathway to high glucose-mediated glycation is an obvious cause. A schematic summary of the findings is shown in Figure 2, which indicates the three hurdles for conventional growth factors during wound closure. Recognitions of these limitations of the growth factor therapy could help to improve future usage of becaplermin gel. For instance, a combined becaplermin gel treatment of DUFs with a TGFβ inhibitor, such as LY-2157299 (currently in clinical trials), or medication with a glucose control drug, such as Lipitor, prior to becaplermin gel treatment may improve the efficacy. Finally, since these limitations associated with PDGF-BB are also inherent in other conventional growth factors, it would be prudent to keep in mind these three salient principles regarding the biology of how skin wounds heal when investigators and pharmaceutical companies attempt to develop other wound healing agents. An important take-home message from these studies is that the conventional growth factors may not be the “driver genes” for wound closure as they were previously believed.

Figure 2. Three hurdles facing growth factor therapy.

The three major skin cell types, keratinocyte, dermal fibroblast and endothelial cells, involved in wound healing are indicated. The conventional growth factors, such as PDGF-BB as shown, cannot be the primary driver of wound closure for three listed reasons: 1) selective cell target that expresses the receptor; 2) sensitive to TGFβ inhibition and 3) compromised effectiveness under pathological conditions.

4. Discovery of secreted Hsp90α as a potential driver molecule for wound closure

If growth factors cannot serve as driver molecules for wound closure, what is the naturally occurring driver molecule(s)? In other words, what different type of molecules is able to overcome the three hurdles facing growth factors and, therefore, effectively promotes wound closure? First, we speculated that this factor cannot come from the circulation due to coagulation and hemostasis, instead it comes from secreted molecules of the keratinocytes at the wound edge under microenvironmental cues [33]. The migrating keratinocytes secrete such unknown factor to the wound bed. Whence this secretedfactor reaches its threshold concentration, it i) promotes keratinocyte migration to close the wound and ii) acts as a chemotaxis factor to recruit the surrounding dermal cells into the wound. Under this guidance, we first demonstrated that a serum-free conditioned medium of hypoxia-induced migrating human keratinocytes contains a robust pro-motility activity for all the human epidermal and dermal cell types. Second, this pro-motility activity could not be blocked by exogenously added human recombinant TGFβ3. Third, multiple rounds of Fast Protein Liquid Chromatography (FPLC) with the sensitive colloidal gold cell migration assay allowed us to purify the pro-motility activity-containing protein from 10 liters of human keratinocyte conditioned medium to a single species of a protein in range of nanograms. Mass spec analysis revealed that this protein is secreted form of Hsp90α. Depletion of Hsp90α from the conditioned medium by immunoprecipitation with a specific neutralizing antibody against Hsp90α (but not Hsp90β) completely eliminated the pro-motility activity from the original conditioned medium. In reverse, the addition of increasing amounts of human recombinant Hsp90α overrode the antibody inhibition and resumed the promotility activity of the conditioned medium in a dose-dependent manner [34].

Bhatia and colleagues recently showed that skin wounding triggers a massive and time-dependent deposition of Hsp90α protein into the wound bed in pigs, which is closest to humans [35]. There IHC analysis revealed that Hsp90α staining was detected only around the keratinocytes at the epidermis on day 0 and a modest increase at both epidermis and dermis on day 2. A dramatic increase in Hsp90α staining throughout the wound bed was detected from day 4 to day 7. Technically speaking, however, the increased Hsp90α staining could result from several possible sources: 1) increased secretion by the cells in the wound, 2) increased expression of Hsp90α inside the cells in the wound; 3) from penetrated immune cells, such as neutrophils and monocytes, to the wound and 4) combinations of the above. The answer remains to be studied. To investigate whether the secreted Hsp90α is essential for wound healing in mice, Bhatia and colleagues then used a unique mouse model that has selectively destroyed the intracellular, but not extracellular, functional entity of Hsp90α by a C-terminal deletion [35]. While the animals were born healthy, this Hsp90α-Δ mouse model allowed the authors to test whether the extracellular and non-chaperone function of secreted Hsp90α is required for normal wound healing, since the Hsp90α-Δ mutant protein still contains the entire F-5 fragment (see later sections) of Hsp90α. It needs to be pointed out that, while this mouse model was initially reported as Hsp90α knockout (KO) [36], Bhatia et al proved for the first time that this previously reported KO model is not as it was reported, rather it is a model expressing a deletion mutant of Hsp90α that no long can act as a chaperone. Exactly for this reason, this model turns out to be the sought-after one to study the non-chaperone and secreted form of Hsp90α. Using so-called “splinted” wounds that show the least contraction and highest level of reepithelialization, these authors found that wound healing in the Hsp90α-Δ mutant mice remain indistinguishable from wound healing in wild type Hsp90α mice. Topical application of recombinant protein generated from the Hsp90α-Δ cDNA promotes wound healing as effectively as the wild type Hsp90α protein. However, direct blockage of the F-5 region of secreted Hsp90αΔ by neutralizing antibody, 1D6-G7, inhibited wound healing in these mice [35]. These findings provide the genetic support for the non-chaperone and secreted form of Hsp90α as a potential driver gene for normal wound closure.

It has been demonstrated that all cell types (except red blood cells) express the Hsp90 family proteins (α and β) at the levels of 2–3% of the total cellular proteins (assuming ~7,000 different proteins per cell on average) and all cells secrete Hsp90α proteins in response to environmental stress signals, including heat, hypoxia, inflammatory cytokines, ROS, oxidation agents, UV, just to mention a few) [37]. While most current technologies do not have the resolution to visualize the secretion in vivo, the best way to prove its presence is to use monoclonal antibodies to block its reported function [35]. Similarly, inhibition of extracellular Hsp90α signaling by blocking its cell surface receptor, LRP-1, delayed normal wound healing [38].

5. Topical application of human recombinant Hsp90α protein promotes wound closure in excision, burn and diabetic wounds in pigs.

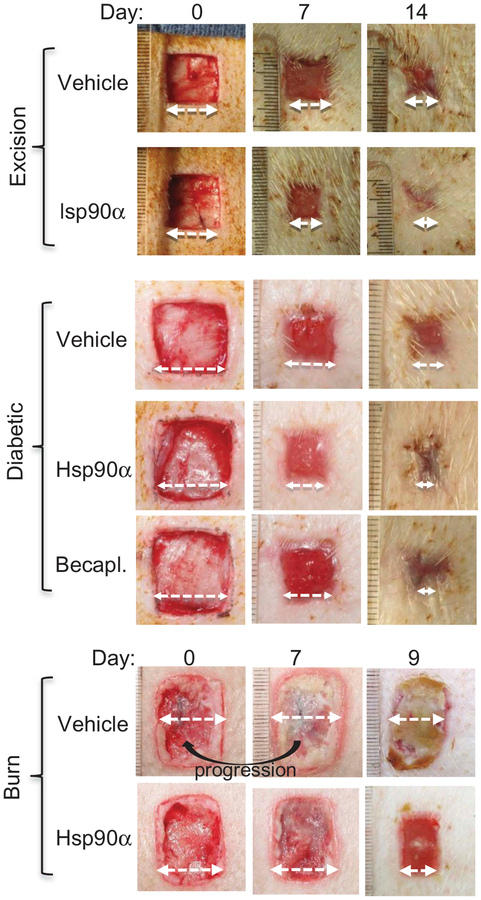

Preclinical studies with topical application of human recombinant Hsp90α have shown a great promise in various wound healing animal models, especially in porcine models. Why are pig models more relevant to humans than rodent models? Rodents such as rats and mice have been widely used animals for skin wound healing studies. However, rodents are loose skin animals and the way they heal skin wounds predominantly by the mechanism of wound contraction (70%) may not translate well to human skin wound healing. Pigs, like human beings, are tight skin animals and heal skin wounds with a larger component of re-epithelialization (i.e. the lateral migration of keratinocytes across the wound bed) 80%) and a smaller component (<20%) of wound contraction. Moreover, pigs are also an effective model for topical medication studies, because multiple groups of replicate wounds can be created in the same pig for studies of comparative agents. In randomized wound healing studies, for instance, there is a high concordance of the results between pigs and humans [39, 40, 41, 42). O’Brien and colleagues re-established several critical parameters for diabetic and burn wound healing using pigs, including the relationship between locations of wound and their healing rates, optimal distance between two wounds, measurements of diabetic biomarkers over time, correlation between diabetic conditions and delay in wound closure, just to mention a few [32]. Using these pig models, these authors presented encouraging results for topically applied Hsp90α protein on full-thickness, diabetic and burn wounds [32, 38, 43]. These findings are summarized in Figure 3, which suggests that topical application of Hsp90α can be used as a general agent for treatment of a wide variety of skin wounds. It remains to be seen whether these effects can translate to human wounds.

Figure 3. Topical Hsp90α promotes closure of excision, diabetic and burn wounds in pigs.

Full-thickness excision wounds of normal or diabetic pigs and burn wounds in triplicates were created on a pig’s torso with 4.0 cm between the wounds. These wounds were either treated with vehicle control or vehicle with human recombinant Hsp90α (100μg/ml). Wound closure was measured up to day 14 (Taken with permissions from O’Brien et al., 2015; Bhatia et al., 2016).

6. Secreted Hsp90 carries three unique properties, absent from conventional growth factors, to more effectively heal wounds.

What makes secreted Hsp90α superior to conventional growth factor therapy, such as becaplermin/PDGF-BB? Cheng et al identified three unique properties of secreted Hsp90α [30], exactly opposite to the three hurdles facing growth factors, as previously discussed. First, unlike growth factors, secreted Hsp90α is a common pro-motility factor for all three types of human skin cells. Following skin injury, the lateral migration of keratinocytes closes wound and subsequent inward migration of dermal fibroblasts and dermal microvascular endothelial cells into the wound remodels the damaged tissue and builds new blood vessels. In contrast, most growth factors, such as PDGF-BB and VEGF-A, have a cell type specificity. The pro-motility activity of extracellular Hsp90α resides in the middle domain plus the charged sequence of Hsp90α, called F-5 (fragment −5), but independent of the Hsp90α’s ATPase activity. It promotes epidermal and dermal cell migration through the surface receptor, LDL receptor-related protein-1 (LRP-1 or CD91). Second, extracellular Hsp90 remains equally effective on all three types of human skin cells even in the presence of TGFβ. Few conventional growth factors can override the inhibition by TGFβ. Third, all forms of diabetes are characterized by chronic hyperglycemia in circulation, which is blamed for the delayed wound healing in diabetic patients. A reported damage by hyperglycemia is destabilization of the hypoxia-inducible protein-1alpha (HIF-1α) protein, a key regulator of Hsp90α secretion [37]. Cheng et al showed that hyperglycemia blocks hypoxia and serum-stimulated human dermal fibroblast migration. However, secreted Hsp90α not only enhances hypoxia-driven migration under normal glycemia, but also “rescues” the migration of the cells cultured under hyperglycemia [30]. These observations suggest that the effectiveness of secreted Hsp90α to promote diabetic wound healing is to bypass the hyperglycemia-caused HIF-1α down-regulation and jumpstart migration of the “diabetic” cells that otherwise do not properly respond to the environmental hypoxia cue. Fourth, extracellular Hsp90α can act as a novel survival factor for cells under hypoxia. Depletion of Hsp90α secretion from certain tumor cells was permissive to cytotoxicity by hypoxia, whereas supplementation of the Hsp90α-knockout cells with recombinant Hsp90α, but not Hsp90β, protein prevented hypoxia-induced cell death via an autocrine mechanism through the LDL receptor-related protein-1 (LRP1) receptor. In reverse, direct inhibition of the secreted Hsp90α by these cells with monoclonal antibody, 1G6-D7, enhanced the cell death under hypoxia [44]. Finally, secreted Hsp90α is an anti-inflammatory factor in vivo. Recombinant Hsp90α-treated burn and excision wounds show a marked decline in inflammation, i.e. much less penetrated neutrophils and granulocytes, although the mechanism of inhibition currently remains unknown [43].

7. Secreted Hsp90 does not require ATPase or dimerization for promoting wound healing.

For the past decade, a critical debate centers on whether the secreted or extracellular Hsp90α protein still acts as a chaperone or it acts independent of the intrinsic ATPase. Now a clear answer is that extracellular Hsp90α does not need its ATPase and acts as a bona fide signaling protein that utilizes a unique trans-membrane signaling pathway. Cheng and colleagues compared recombinant proteins of the wild type and E47A, E47D, and D93N mutants of Hsp90α for pro-motility activity on human keratinocytes. As previously reported, Hsp90α-wt has a full ATPase activity, Hsp90α-E47D mutant loses half of the ATPase activity, whereas Hsp90α-E47A and Hsp90α-D93N mutants lose the entire ATPase activity [45]. Cheng et al found that all the ATPase mutant proteins retained a similar pro-motility activity as the Hsp90α-wt. Second, they used sequential deletion mutagenesis to narrow down the pro-motility domain to a 115-amino acid fragment, called F-5 (aa-236 to aa-350), that promotes skin cell migration in vitro and wound healing in vivo as effectively as the full-length Hsp90α-wt [30, 34]. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that the N-terminal ATPase domain and the C-terminal dimer-forming and co-factor-binding domain are dispensable for extracellular Hsp90α to promote cell migration and wound healing. The amino acid sequence of F-5 is highly conserved during evolution in the Hsp90α subfamily. In contrast, no more than 20% amino acid identity of F-5 was found in other HSP family members. The preclinical studies with topical application of F-5 greatly promotes wound closure in rodent and pig models [30, 32, 35].

Further efforts to establish the minimum size of the new drug entity of Hsp90α for treatment of wounds have been made by using sequential deletion mutagenesis. Interestingly, these approaches led to identification of a 27-amino acid peptide, called F-8 (fragment-8). O’Brien et al reported several unique features about F-8: 1) F-8 retains a full pro-motility activity of the full-length Hsp90α - the standard; 2) F-8 alone was unable to promote wound healing in vivo, due to its compromised stability in the wound environment and 3) However, linking F-8 to a “carrier protein” such as glutathione-s-transferase (GST) was sufficient to promote wound healing as much as GST-Hsp90α-wt did [32]. In theory, the size of F-8 makes it less immunogenic, less off target effects and easier to manufacture. These are the sought-after properties for treatment of acute, such as burn, wounds in healthy patients, especially significant for burn-injured solders in the battle field.

8. The mechanism of action by secreted/extracellular Hsp90α

Among a handful targets reported for extracellular Hsp90α signaling, only LRP-1 has been thoroughly shown to act as the cell surface receptor for extracellular Hsp90α signaling [37]. It was estimated that secreted Hsp90α from keratinocytes could readily reach its optimal working concentration of 0.05–0.1μM that maximally stimulates cell migration in vitro [34]. Under in vitro cell migration assays, human recombinant Hsp90α exhibited saturating and subsequently declined effects on human skin cells, when increasing amounts of Hsp90α protein were added. These data suggest that extracellular Hsp90α acts by binding to a receptor-like molecule on the cell surface following the Michaelis–Menten plot principle. To demonstrate that the ubiquitously expressed LRP-1 mediates extracellular Hsp90α signaling to promote cell migration, Cheng et al used four independent approaches. First, neutralizing antibodies against LRP-1, which block its ligand biding site, inhibit extracellular Hsp90-stimulated cell migration. Second, the addition of RAP (LRP-1-associated protein), which is known to block ligand binding to LRP-1, to the medium nullifies the extracellular Hsp90α function. Third, down-regulation of endogenous LRP-1 by RNAi blocks cell migration in response to extracellular Hsp90α. Fourth, re-introduction of an RNAi-resistant mini-LRP-1 cDNA into the LRP1-downregulated cells rescues the migration response of the cells to extracellular Hsp90α and hypoxia. Consistently, GST-Hsp90 directly pulled down LRP-1 via its pro-motility fragment between the LR and the M domain of Hsp90α [34. 46]. Moreover, Tsen and colleagues elucidated a more detailed signaling pathway for extracellular Hsp90α. Their report showed that subdomain II in the extracellular part of LRP-1 receives extracellular Hsp90α signal. Then, the NPVY, but not NPTY, motif in the cytoplamic tail of LRP-1 connects extracellular Hsp90α signaling to the serine-473, but not threonine-308, phosphorylation in Akt kinases. Individual knockdown of Akt1, Akt2 or Akt3 demonstrates the importance of Akt1 and Ak2 in extracellular Hsp90α signaling in control of cell motility in vitro. Finally, Akt1- and Akt2- knockout mice showed impaired wound healing that could not be corrected by topically applied recombinant Hsp90α. These findings led the investigators to propose the following working model: “Hypoxia > HIF-1α > Hsp90α secretion > LRP-1’s sub-domain-II > Akt1/2 > cell motility” pathway for wound healing [47].

The complexity of LRP-1 signal transduction also comes from its large ligand binding repertoire and its interactions with numerous other cell surface proteins, whose specific binding sites in LRP-1 remains to be individually identified. For instance, besides Hsp90α, other extracellular heat shock proteins that also bind LRP-1 include gp96, calreticulin, Hsp60 and Hsp70 [48–51]. In addition, LRP-1 has also been shown to play a critical role in PDGF-BB-stimulated ERK1/2 activation and cell proliferation and TGFβ-stimulated anti-proliferation [48]. Using purified Hsp90 proteins, our group showed that extracellular Hsp90α has little mitogenic effect on cells. While extracellular Hsp90α

stimulation dramatically increases cell migration, Hsp70, gp96 and calreticulin exhibit either a modest or no stimulation of cell migration [33, 34].

9. Secretion of Hsp90α via the non-classical exosomal protein trafficking pathway

Two lines of evidence for exosome-mediated secretion of Hsp90α came from proteomic [49] and electron microscopy [50] analyses. In cells, there are several cellular protein trafficking machineries. First, the classical ER/Golgi protein secretory pathway requires any to-be-secreted protein to have a 15–30 amino acid signal peptide (SP) at its amino terminus and use it as the “permit” for going out of the cell. The second protein secretory pathway is mediated by secreted nano-vesicles, called exosomes, which are used for secreting proteins that do not have any SP sequences. Exosomes, also called ‘intraluminal vesicles’ (ILVs), are non-plasma-membrane-derived vesicles that are 30–150nm in diameter and initially contained within the multivesicular bodies (MVB). A well-known function of MVB is to serve as an intermediate station during degradation of the proteins internalized from the cell surface or sorted from the trans Golgi organelle [51, 52]. The MVB-derived exosomes can also fuse with the plasma membrane to release their cargo proteins into the extracellular space. This release process was reported to include 1) sorting into smaller vesicles; 2) fusing with the cell membrane; and 3) release of the vesicles to the extracellular space. All proteins that have been identified in exosomes reside in the cell cytosol or endosomal compartments, but never in the ER, Golgi apparatus, mitochondria or nucleus. Making use of two chemical inhibitors, brefeldin A (BFA) that selectively blocks the classical ER/Golgi protein secretory pathway and dimethyl amiloride (DMA) that blocks the exosome protein secretory pathway, a number of research groups showed that DMA selectively inhibits the membrane translocation and secretion of Hsp90α and/or Hsp90β in various types of cells [34, 53, 54, 55]. Under similar conditions, BFA had little inhibition of Hsp90 secretion [56]. An important question is how the extracellular, such as hypoxia and H2O2, and intracellular, such as HIF-1α, stress signals are connected to this novel protein secretory pathway. Moreover, once Hsp90α proteins are secreted to outside the cells, they appear to be at the surface of exosomes, instead of continued being “wrapped” inside the exosomes, since neutralizing anti-Hsp90α antibodies completely block its action from ultracentrifugation (100,000g)-isolated exosomes [33, 34, 56, 57].

10. Extracellular Hsp90 was overlooked for decades.

In fact, it has been more than two decades, since extracellular Hsp90 was first reported as a cell-surface bound tumor antigen [58]. For years, skepticisms remained as whether extracellular Hsp90 proteins are results of pathophysiological processes in the cells or of release from a small portion of dead cells in culture [59]. A primary reason for the skepticism is that Hsp90 does not fit into the conventional category of actively secreted proteins, such as growth factors, extracellular matrices (ECMs) and matrix metaloproteinases (MMPs). First, Hsp90 has neither a signal peptide (SP) for secretion via the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)/Golgi protein secretory pathway nor a recognizable transmembrane sequence for membrane anchoring. Second, there have been reports that Hsp90 could indeed be released to extracellular environment following cell necrosis [54], which in turn binds and helps antigen recognition and triggers immune responses.

Studies of the past decade have provided additional lines of evidence that cells actively export Hsp90α for purpose. An overall take-home message is that cells secrete Hsp90α once they encounter environmental stress and the purpose of the secretion is protection and repair. The reported environmental cues that trigger cells to secrete Hsp90 (α and β) include reactive oxygen species (ROS), heat, hypoxia, gamma-irradiation and injury-released growth factors. First, Hightower and Guidon reported that heat-shocked rat embryonic cells secreted Hsp90 and Hsp70, which could not be blocked by monensin or colchicine, inhibitors of the conventional protein trafficking pathway [60]. When Clayton and colleagues used proteomic methods to analyze the peptide contents of B cell-secreted exosomes under either a physiological temperature (37 °C) or heat shock (42 °C for 3 hours), they found that heat induces Hsp90 secretion among other heat shock proteins into the nano-vesicles called exosomes [49]. Similar observations were made for Hsp70 via the exosome-dependent trafficking pathway in different cell types [57]. Second, Liao et al reported that two-hour treatment of rat vascular smooth muscle cells with LY83583, an oxidative stress generator, caused secretion of Hsp90 and a late phase activation of ERK1/2 by the oxidative stress [61]. Ito and colleagues reported that the oxidative stress induced by H2O2 enhanced the release of Hsp70 and Hsp90. whereas antioxidants suppressed the release of these cytosolic proteins induced by H2O2 treatment during wound healing in brain [62]. Third, Yu and colleagues found that γ irradiation induces secretion of Hsp90β via a p53-dependent event into conditioned medium, suggesting a “DNA damage > p53 > secretion of Hsp90β” pathway [50]. Fourth, Li and colleagues showed that hypoxia causes increased skin fibroblast migration and Hsp90α secretion via elevated HIF-1α. Blockade of the extracellular Hsp90α function by neutralizing antibodies completely inhibited hypoxia’s pro-motility effect on the cells, suggesting that secretion of Hsp90α is part of hypoxia’s pro-motility signaling [33]. Cheng et al. showed that TGFα rapidly induces Hsp90α membrane translocation and secretion to an extracellular environment in primary human keratinocytes [34]. Since TGFα level is undetectable in human plasma (i. e. unwounded skin) and dramatically increased in serum (i. e. wounded skin), keratinocytes only become in contact with TGFα after the skin is wounded [34]. Therefore, the action of TGFα on keratinocytes is considered as a pathophysiological stress. Our group went further to have identified LRP-1/CD91 as the cell surface receptor that mediates Hsp90α-stimulated migration of human keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts. They demonstrated that cells without LRP-1 completely lost pro-motility response to recombinant Hsp90α or hypoxia [34, 45]. Since overexpression of HIF-1α has been reported in ~50% of all invasive tumors in humans, the overexpressed HIF-1α should cause constitutive surface expression and secretion of Hsp90α in those tumor cells. This is indeed the case. Kuroita and colleagues reported purification of Hsp90α from conditioned media of human hybridoma SH-76 cells [63]. Eustace et al reported that Hsp90α, but not Hsp90β, was secreted into the conditioned media of HT-1080 tumor cells [64]. Wang et al reported secretion of Hsp90α by MCF-7 human breast cells [65]. Suzuki and Kulkarni found Hsp90β secreted by MG63 osteosarcoma cells [66]. Chen and colleagues reported secretion of Hsp90α by colorectal cancer cell line, HCT-8 [67]. Results of a study by Tsutsumi and colleagues implied secretion of Hsp90α by a variety of tumor cell lines [68]. Finally, Sahu and colleagues demonstrated that breast cancer cells, MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468, overexpress HIF-1α that causes constitutive secretion of Hsp90α in a HIF-1-depemndent fashion [57]. In conclusion, it is becoming increasingly clear that normal cells secrete Hsp90 for tissue repair, whereas tumor cells constitutively secrete Hsp90 for invasion and metastasis [37].

11. Importance of human disease-relevant animal models for drug development

Drug development is difficult and fraught with failure. Despite significant investment in new therapeutic agents supported by laboratory findings and pre-clinical animal models, less than 5% of these agents are successful in obtaining FDA-approval for clinical use in human patients. One of the main reasons is lack of relevant animal models for the given human disorder, especially such chronic diseases as atherosclerosis, diabetes and cancer. There is no animal model for chronic or non-healing skin wounds that are relevant to the pathophysiology of human chronic wounds - a major hurdle for development of effective therapeutics. Diabetes mellitus (DM), for example, is a group of metabolic diseases when the body has too little insulin or when the body can’t use insulin properly. If the condition has persisted over a prolonged period of time, it results in high blood sugar levels. Acquired type II diabetes accounts for 90% of all diabetic patients, and these patients have had chronically elevated blood glucose levels (over 125 mg/dl) for many years. The average onset of the disease is age 40, approximately the 50% lifespan of human beings. As mentioned previously, pigs are the preferred animal model for wound healing studies than rodents [39]. However, most of the pig studies to date used young pigs (2–4 months, less than 5% their normal lifespan) with induced relatively a brief period of hyperglycemia, usually only a few weeks. Few of these studies show similar pathological changes in the skin as diabetic humans who exhibit increased glycation within the skin dermis (Note: glycation is a form of nonenzymatic glycosylation that causes reduced functionality of the modified protein in cells and tissues [69, 70]. Therefore, in addition to identification of the “driver genes”, greater efforts to establish animal models that resemble the human disorders are among the urgent solutions. Unfortunately grant proposals on this (important) topic are often regarded as “non-hypothesis-driven”, “incremental” or “lack of innovation”, and unanimously rejected. This attitude must change or the long wait for effective wound healing therapeutics continues.

12. A double-edged sword for targeting secreted Hsp90 for drugs

Mechanistically, wound healing and tumor progression share similar traits [71]. Studies of the past few years have begun to reveal a picture for when, how and why Hsp90 get exported not only by normal but also by many types of tumor cells. Normal cells secrete Hsp90α in response to tissue injury. Tumor cells have managed to constitutively secrete Hsp90 for tissue invasion. In either case, sufficient supply of the extracellular Hsp90 can be guaranteed by its unusually abundant storage inside the cells. A well-characterized function of secreted Hsp90α is to promote cell motility, a crucial event shared by wound healing and cancer progression. Inhibition of its secretion, neutralization of its extracellular action or interruption of its signaling through the LRP-1 receptor blocks wound healing and tumor invasion in vitro and in vivo [37]. In normal tissue, topical application of Hsp90α promotes acute and diabetic wound healing far more effectively than US FDA-approved conventional growth factor therapy in mice [30]. In cancer, drugs that selectively target the F-5 region of secreted Hsp90 by cancer cells may be more effective and less toxic than those that target the ATPase of the intracellular Hsp90 [72]. Therefore, a potential clinical contradiction is that we need extra secreted Hsp90 to repair injured tissues, whereas we also have to take caution of the tumor-secreted Hsp90 that supports tumor progression. These factors must be taken into account during clinical trials and treatments of patients.

13. Conclusion

A fundamental question is why Hsp90α is chosen (by Mother Nature) as an extracellular factor for wound healing. Two speculations were offered. First, Hsp90 accounts for 2–3% of the total cellular protein [32], a luxury that evolution seldom tolerates otherwise. Therefore, the function of Hsp90 cannot be restricted only to an intracellular chaperone, but rather it plays another unrecognized role that would require such a large amount of pre-stored Hsp90 [61]. For tissue repair, for instance, having a large amount of Hsp90α constantly stored enables the cells at the injured site quickly respond to stress. Second, tissue repair, as well as cancer progression, must overcome inhibitory signals of the TGFβ family cytokines. Extracellular Hsp90α promotes tissue repair even in the presence of TGFβ [34]. We believe that this unique property of extracellular Hsp90α is the main reason for its superior effect over FDA-approved growth factor therapy in skin wound healing, so far in animal models. Third, the fact that extracellular Hsp90α is a motogen, but not a mitogen (i.e. it does not stimulate cell proliferation) also makes a physiological sense. First, cell migration proceeds cell proliferation during wound healing. Keratinocyte migration occurs almost immediately following skin injury (within hours), whereas the inward migration of dermal cells is not detected until four days later [1]. When a cell is migrating, it cannot proliferate at the same time [31]. After the cells at the wound edge are moving toward the wound bed, they left “empty space” between themselves and the cells behind them, so that the cell-cell contact inhibition gets released. The cells behind the migrating cells start to proliferate. The stimuli of the cell proliferation likely come from plasma growth factors diffused from surrounding unwounded blood vessels, where TGFβ levels are low or undetectable. Thus, the role of cell proliferation in wound healing is to re-fill the space generated by the front-migrating cells. The specific role for extracellular Hsp90α is to help to achieve the initial wound closure as quickly as possible to prevent infection, water loss, and severe environmental stress. Many other factors, including conventional growth factors, will participate in the remaining long and tedious wound maturation process.

14. Expert commentary

The care for human skin wounds, including venous stasis ulcers, pressure ulcers and diabetic foot ulcers wounds costs the United States ~$11 billion/year. For example, the number of lower extremity amputations is approaching 100,000 in the US mainly due to non-healing diabetic ulcers, in which a single surgical procedure and hospitalization alone can cost up to $70,000. The currently available treatment shows moderate efficacy and yet is very expensive, such as becaplermin gel (0.1% PDGF-BB). Treating a single diabetic foot wound costs up to $28,000 within a 24-month period. Similar reality faces many other types of chronic wounds, whose therapeutic development is being delayed because there has been lack of any animal models that resemble these chronic human disorders. Wound closure on time is as critical as saving life and, therefore, should have been the focus of the research and drug development. Demands for understanding wound maturation or even wound regeneration to its original form may be the ultimate goals, yet in humans they face as unrealistic hurdles as attempts to reverse the evolutionary progression, i.e. human beings may never (re-) acquire the regenerating capability they left for lizards hundreds of million years ago. This article raises a critical question of what nature of the physiological factor(s) responsible for driving wound closure is. Specifically, what factor(s) drives the lateral migration of epidermal keratinocytes over the wound bed to close the wound and it in turn attracts the inward migration of dermal fibroblasts and microvascular endothelial cells into the wound bed to further support completion of the keratinocyte migration-led re-epithelialization event. The role for these moved-in dermal cells is to replenish the damaged connective tissue and to build a new vascularized neodermis for supply of oxygen and nutrients. For decades, the unchallenged answer and focus of wound therapeutic development are on “growth factors”. Growth factors indeed play an essential role during wound healing, yet the unanswered question is at what stage(s) of wound healing that requires the growth factor involvement. Studies of the past ten years suggest that growth factors do not seem be the primary factors that respond to the injury-caused environmental stress. Instead, they likely play a critical role in later stages of wound healing following wound closure, especially during the wound maturation phase. One reason is that increasing growth factor levels would require transcriptional activation of the genes and de novo protein synthesis, which will take time to build up to the threshold concentrations, not to mention their poor stability records in the wound microenvironment. Using growth factors for the initial and critical wound closure purpose is likely to build up fire stations in a community after the fire breaks out. Instead, it makes sense for pre-existing and stockpiled molecule(s) to quickly respond to the injury and take on the responsibility of promoting wound closure. If this is the case, a paradigm shift may provide hope to end the continued lack of effective treatments of wounds. This review has discussed one such possible alternative – the HSP family proteins by focusing on the secreted from of Hsp90α by cells under stress. So far, results of preclinical studies in various animal models support the hypothesis. Genetic study indicates that stress-induced secretion of Hsp90α is on the driver seat for wound closure. Translation of these results to human patients remains to be seen.

15. Five-year view

Two research directions and one essential tool will determine the future outcomes of wound healing therapeutics. First, greater efforts must be made on identification of the driver genes for wound closure. Second, the stem cell therapy of wounds may show a breakthrough, which is beyond the topic of this review. After all, a bigger problem in current wound healing field is lack of relevant animal models, especially for chronic wounds.

16. Key issues.

What are the “driver genes” for wound healing, especially during the wound closure phase?

How to establish animal models that closely resemble the human disorders, such as chronicity of the disease, for developing effective therapeutics?

Are chronic wounds really a skin problem or should be treated as systemic disorders?

Is secreted Hsp90α a general “repair” molecule in our body?

Acknowledgements

We thank USC Pathology Core for preparations of tissue histology slides.

Funding

This study is supported by United States Department of Health National Institutes of Health grants: GM066193 and GM067100 (WL), AR46538 (DTW), AR33625 (MC and DTW) and VA Merit Award (DTW).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reference

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

* of interest

** of considerable interest

- 1.Singer A and Clark R. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1999; 341:738–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin P Wound healing--aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science. 1997; 276: 75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi S, Lee S, Kim Y, et al. Role of heat shock proteins in gastric inflammation and ulcer healing. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009; 60:5–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atalay M, Oksala N, Lappalainen J, et al. Heat shock proteins in diabetes and wound healing. Current Protein and Peptide Science. 2009; 10:85–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magalhães W, Nogueira M, Kaneko T. Heat shock proteins (HSP): dermatological implications and perspectives. European Journal of Dermatology. 2012; 22:8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellaye P, Burgy O, Causse S, et al. Heat shock proteins in fibrosis and wound healing: good or evil?. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2014; 143:119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Werner S, Grose R. Regulation of wound healing by growth factors and cytokines. Physiol Rev. 2003; 83:835–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grose R, Werner S. Wound-healing studies in transgenic and knockout mice. Mol Biotechnol. 2004;28:147–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LeGrand E, Preclinical promise of becaplermin (rhPDGF-BB) in wound healing. Am J Surg. 1998; 176:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown G, et al. Enhancement of wound healing by topical treatment with epidermal growth factor. N Engl J Med. 1989; 321:76–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pastor J, Calonge M. Epidermal growth factor and corneal wound healing. A multicenter study. Cornea. 1992; 11:311–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramsay H, Heikkonen E, Laurila P. Effect of epidermal growth factor on tympanic membranes with chronic perforations: a clinical trial. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995; 113:375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez-Montequin J Intralesional injections of Citoprot-P (recombinant human epidermal growth factor) in advanced diabetic foot ulcers with risk of amputation. Int Wound J. 2007; 4:333–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohan V Recombinant human epidermal growth factor (REGEN-D 150): effect on healing of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007; 78:405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenhalgh D, Rieman M. Effects of basic fibroblast growth factor on the healing of partial-thickness donor sites. A prospective, randomized, double-blind trial. Wound Repair Regen. 1994; 2:113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu X, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of use of topical recombinant bovine basic fibroblast growth factor for second-degree burns. Lancet. 1998; 352:1661–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uchi H, et al. Clinical efficacy of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) for diabetic ulcer. Eur J Dermatol. 2009; 19:461–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma B, et al. Randomized, multicenter, double-blind, and placebo-controlled trial using topical recombinant human acidic fibroblast growth factor for deep partial-thickness burns and skin graft donor site. Wound Repair Regen. 2007; 15:795–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robson M, et al. Sequential cytokine therapy for pressure ulcers: clinical and mechanistic response. Ann Surg. 2000; 31:600–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robson M, Phillips L, Thomason A, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor BB for the treatment of chronic pressure ulcers. Lancet. 1992; 339:23–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pierce G, Tarpley J, Yanagihara D, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor (BB homodimer), transforming growth factor-beta 1, and basic fibroblast growth factor in dermal wound healing. Neovessel and matrix formation and cessation of repair. Am J Pathol. 1992; 140:1375–1388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steed D Clinical evaluation of recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor for the treatment of lower extremity diabetic ulcers. Diabetic Ulcer Study Group. J Vasc Surg. 1995; 21:71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LeGrand E Preclinical promise of becaplermin (rhPDGF-BB) in wound healing. Am J Surg. 1998; 176:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smiell J, Wieman T, Steed D, et al. Efficacy and safety of becaplermin (recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB) in patients with nonhealing, lower extremity diabetic ulcers: a combined analysis of four randomized studies. Wound Repair Regen. 1999; 7:335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wieman T, Smiell J, Su Y. Efficacy and safety of a topical gel formulation of recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB (becaplermin) in patients with chronic neuropathic diabetic ulcers. A phase III randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Diabetes Care. 1998; 21:822–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagai M, Embil J. Becaplermin: recombinant platelet derived growth factor, a new treatment for healing diabetic foot ulcers. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2002; 2:211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mandracchia V, Sanders S, Frerichs J. The use of becaplermin (rhPDGF-BB) gel for chronic nonhealing ulcers. A retrospective analysis. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2001; 18:189–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bejcek B The v-sis oncogene product but not platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) A homodimers activate PDGF alpha and beta receptors intracellularly and initiate cellular transformation. J Biol Chem. 1992; 267:3289–3293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van den Dolder J, Mooren R, Vloon A, et al. Platelet-rich plasma: quantification of growth factor levels and the effect on growth and differentiation of rat bone marrow cells. Tissue Eng. 2006; 12:3067–3073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng C, Sahu D, Tsen F, et al. A fragment of secreted Hsp90α carries properties that enable it to accelerate effectively both acute and diabetic wound healing in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011; 121:4348–4361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This study compares topical Hsp90α protein with growth factor therapy to promote acute and diabetic wound healing in mice, demonstrates that secreted Hsp90α does not need its ATPase, and identify the drug entity called “F-5”.

- 31.Bandyopadhyay B, Fan J, Guan S, et al. A “traffic control” role for TGFbeta3: orchestrating dermal and epidermal cell motility during wound healing. J Cell Biol. 2006; 172:1093–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Brien K, Bhatia A, Tsen F, et al. Identification of the critical therapeutic entity in secreted Hsp90α that promotes wound healing in newly re-standardized healthy and diabetic pig models. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This study demonstrates an efficacy of topical Hsp90α protein in diabetic wound healing in pigs and further narrows the drug entity down to a 27-amino acid peptide, called “F-8”.

- 33.Li W Extracellular heat shock protein-90alpha: linking hypoxia to skin cell motility and wound healing. EMBO J. 2007; 26:1221–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This is the first report for discovery of secreted Hsp90α protein for promoting cell migration and wound healing.

- 34.Cheng C Transforming growth factor alpha (TGFα)-stimulated secretion of Hsp90α: using the receptor LRP-1/CD91 to promote human skin cell migration against a TGFbeta-rich environment during wound healing. Mol Cell Biol. 2008; 28:3344–3358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhatia A, O’Brien K, Guo J et al. , Requirement for Injury-Induced Deposition and Function of Secreted Heat Shock Protein-90alpha (Hsp90α) during Normal Wound Healing. 2017. under submission; *This mouse genetic study confirms that secreted Hsp90α is a “driver gene” for wound closure.

- 36.Imai T, Kato Y, Kajiwara C, et al. Heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) contributes to cytosolic translocation of extracellular antigen for cross-presentation by dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011; 108:16363–16368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li W, Sahu D, and Tsen F Secreted heat shock protein-90 (Hsp90) in wound healing and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012; 1823: 730–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jayaprakash P, Dong H, Zou M, Bhatia A, O’Brien K, Chen M, et al. Hsp90α and Hsp90β together operate a hypoxia and nutrient paucity stress-response mechanism during wound healing. J Cell Sci. 2.15; 128:1475–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sullivan T, Eaglstein W, Davis S, et al. The pig as a model for human wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2001; 9:66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brahmatewari J, Serafini A, Serralta V, et al. The effects of topical transforming growth factor-beta2 and anti-transforming growth factor-beta2,3 on scarring in pigs. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000; 4:126–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis C, Cazzaniga A, Eaglstein W, et al. Over-the-counter topical antimicrobials: effective treatments? Arch Dermatol Res. 2005; 297:190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindblad W Considerations for selecting the correct animal model for dermal wound-healing studies. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2008; 19:1087–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhatia A, O’Brien K, Chen M, et al. Dual therapeutic functions of F-5 fragment in burn wounds: preventing wound progression and promoting wound healing in pigs. Molecular Therapy. Methods & Clinical Development. 2016; 3:16041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This study confirms the second biological function of secreted Hsp90α in cell survival in vivo.

- 44.Dong H, Zou M, Bhatia A, et al. Breast Cancer MDA-MB-231 Cells Use Secreted Heat Shock Protein-90alpha (Hsp90α) to Survive a Hostile Hypoxic Environment. Sci Rep. 2016; 6:20605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This study reveals the second biological function, in addition to promoting cell migration, of secreted Hsp90α protein to protect cell from hypoxia-caused cell death in vitro.

- 45.Young J, Moarefi I, Hartl F. Hsp90: a specialized but essential protein-folding tool. J Cell Biol. 2001; 154:267–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woodley D, Fan J, Cheng C, et al. Participation of the lipoprotein receptor LRP1 in hypoxia-HSP90alpha autocrine signaling to promote keratinocyte migration. J Cell Sci. 2009; 122:1495–1498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsen F, O’Brien K, Cheng C et al. , eHsp90 (Extracellular Heat Shock Protein 90) Signals Through Subdomain II and NPVY Motif of LRP-1 Receptor to Akt1 and Akt2: A Circuit Essential for Promoting Skin Cell Migration In Vitro and Wound Healing In Vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2013; 33:4947–4953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This study reveals the detailed signaling mechanism by which secreted Hsp90α binds to LRP-21 receptor and promotes cell survival, cell motility and wound healing.

- 48.Lillis A, Van Duyn L, Murphy-Ullrich J, et al. LDL receptor-related protein 1: unique tissue-specific functions revealed by selective gene knockout studies. Physiol Rev. 2008; 88:887–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clayton A, Turkes A, Navabi H, et al. Induction of heat shock proteins in B-cell exosomes. J Cell Sci. 2005; 118:3631–3638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu X, Harris S, Levine A. The regulation of exosome secretion: a novel function of the p53 protein. Cancer Res. 2006; 66:4795–4801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Denzer K, Kleijmeer M, Heijnen H, et al. Exosome: from internal vesicle of the multivesicular body to intercellular signaling device. J Cell Sci. 2000; 113:3365–3374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thery C, Zitvogel L, Amigorena S. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002; 2:569–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lancaster G, Febbraio M. Exosome-dependent trafficking of HSP70: a novel secretory pathway for cellular stress proteins. J Biol Chem. 2005; 280:23349–23355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Savina A, Furlan M, Vidal M, et al. Exosome release is regulated by a calcium-dependent mechanism in K562 cells. J Biol Chem. 2003; 278:20083–20090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hegmans J, Bard M, Hemmes A, et al. Proteomic analysis of exosomes secreted by human mesothelioma cells. Am J Pathol. 2004; 164:1807–1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guo J, Jayaprakash P, Dan J, Wise P, Jang GB, et al. PRAS40 Connects Microenvironmental Stress Signaling to Exosome-Mediated Secretion. Mol Cell Biol. 2017; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sahu D, Zhao Z, Tsen F, et al. Identification of a novel tumor epitope in secreted Hsp90α for HIF-1α-overexpressing breast cancer. Mol. Biol. Cell 2011; 23:602–613.22190738 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Csermely P, Schnaider T, Soti C, et al. The 90-kDa molecular chaperone family: structure, function, and clinical applications. A comprehensive review, Pharmacol Ther. 1998; 79:129–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Multhoff G, Hightower L. Cell surface expression of heat shock proteins and the immune response. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1996; 1:167–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hightower L, Guidon P. Selective release from cultured mammalian cells of heat-shock (stress) proteins that resemble glia-axon transfer proteins. J Cell Physiol. 1989; 138:257–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liao D, Jin Z, Baas A, et al. Purification and identification of secreted oxidative stress-induced factors from vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2000; 275:189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ito J, Nagayasu Y, Hoshikawa M et al. Enhancement of FGF-1 release along with cytosolic proteins from rat astrocytes by hydrogen peroxide. Brain Res. 2013; 1522:12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kuroita T, Tachibana H, Ohashi H. Growth stimulating activity of heat shock protein 90 alpha to lymphoid cell lines in serum-free medium. Cytotechnology. 1992; 8:109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eustace B, Sakurai T, Stewart J, et al. Functional proteomic screens reveal an essential extracellular role for hsp90 alpha in cancer cell invasiveness. Nat Cell Biol. 2004; 6:507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang X, Song X, Zhuo W, et al. The regulatory mechanism of Hsp90alpha secretion and its function in tumor malignancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21288–21293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suzuki S, Kulkarni A, Extracellular heat shock protein HSP90beta secreted by MG63 osteosarcoma cells inhibits activation of latent TGF-beta1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010; 398:525–5331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen J, Hsu Y, Chen C, et al. Secreted heat shock protein 90alpha induces colorectal cancer cell invasion through CD91/LRP-1 and NF-kappaB-mediated integrin alphaV expression. J Biol Chem. 2010; 285:25458–25466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tsutsumi S, Scroggins B, Koga F,et al. A small molecule cell-impermeant Hsp90 antagonist inhibits tumor cell motility and invasion. Oncogene. 2008; 27:2478–2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aubert C, Michel P, Gillery P, et al. Association of peripheral neuropathy with circulating advanced glycation end products, soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products and other risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2014; 30:679–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bos D, de Ranitz-Greven W, de Valk H. Advanced glycation end products, measured as skin autofluorescence and diabetes complications: a systematic review. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011; 13:773–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dvorack H, Tumors: wounds that do not heal. The New Eng. J. Med 1986; 315:1650–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zou M, Bhatia A, Dong H, et al. Evolutionarily conserved dual lysine motif determines the non-chaperone function of secreted Hsp90alpha in tumor progression Oncogene. 2017; 36:2160–2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]