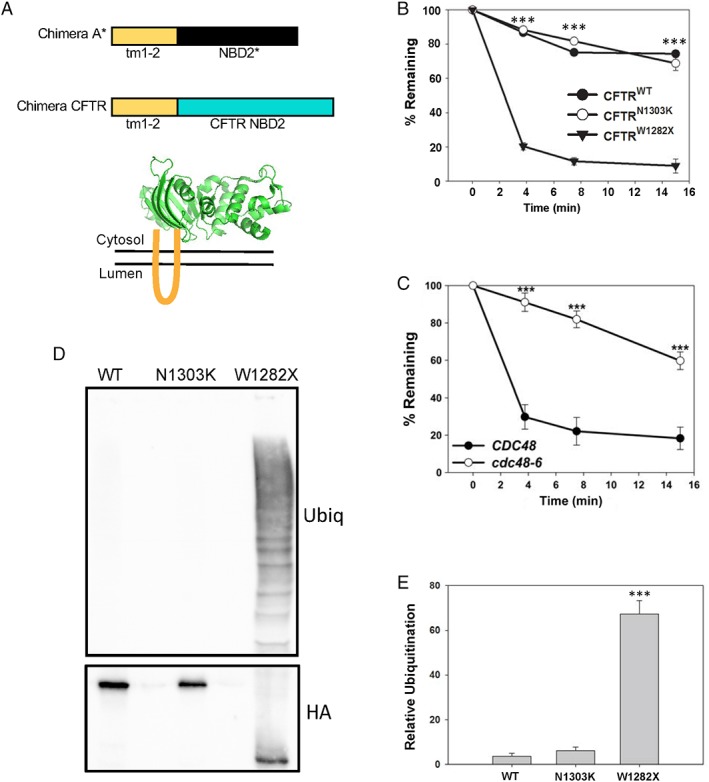

Figure 1.

Truncation of a nucleotide‐binding domain destabilizes a CFTR‐derived chimeric protein. (A) Top, schematic of the new CFTR chimera described in this report in comparison to Chimera A.21 The “tm1‐2” sequence is derived from Chimera A, and the NBD2 of Ste6 and CFTR, depicted in black and blue, respectively, are ~20% identical. Bottom, tm1‐2 (in orange) links the chimera to the ER membrane, and NBD2 is displayed in the yeast cytosol. Representative structure of the NBD2 from CFTR is modified from the PDB (3GD7). (B) Metabolic stabilities of the WT and N1303K and W1282X mutant forms of the CFTR‐derived chimeras were determined by cycloheximide chase at 26°C. The results from three independent experiments, ±SEM, are shown. (C) Metabolic stability of the W1282X mutant form of the CFTR‐derived chimera was determined by cycloheximide chase in WT (CDC48) and cdc48‐6 yeast. Cells were grown at 26°C and then shifted to 39°C for 3 h prior to the start of the chase to induce the mutant phenotype. The results from eight independent experiments, ±SEM, are shown. (D) The level of chimera ubiquitination was examined in a WT yeast strain grown at 26°C. Cells were lysed and the designated proteins were isolated after immunoprecipitation using anti‐HA‐conjugated agarose beads to precipitate the chimera. Western blotting was then performed to detect the substrate (HA) and ubiquitin. (E) Quantification of results from 6 to 10 independent experiments, ±SEM, are shown. *** denotes P < 0.001.