ABSTRACT

Background: To date, most studies on the mental health of refugees in Europe have focused on the prevalence and treatment of psychopathology. Little is known about those who illegally reside in the host country, referred to, in the Netherlands, as undocumented asylum seekers. There are indications that mental health and psychosocial problems are more prevalent in this group than among refugees in general, with unsatisfactory treatment outcomes.

Objective: To describe characteristics and mental health and psychosocial problems of undocumented asylum seekers, and to establish the need for, and feasibility of, a tailored treatment approach.

Method: Based on a literature review and extensive clinical experience, common mental health and psychosocial problems and accessibility of care for undocumented asylum seekers are established, as well as the common treatment approach in the Netherlands. A tailored treatment programme and experiences with its implementation are described.

Results: Mental health and psychosocial problems are highly prevalent among undocumented asylum seekers, and access to care is limited. In addition, treatment in the Netherlands, if provided, is mostly insufficient yet prolonged. Given the specific psychosocial problems and living conditions of undocumented asylum seekers, a necessary criterion to enable adequate and evidence-based treatment provision is acknowledgement of their distinct needs. A tailored treatment programme as currently implemented in the Netherlands appears to meet this criterion and be feasible under certain conditions. Collaboration between mental health care providers and involved social service and governmental parties by regular meetings, though complicated, is a relevant element.

Conclusions: Even though undocumented asylum seekers are illegally residing in a country, medical ethics and the human rights perspective necessitate for adequate and evidence-based treatment for those among them with mental health problems. The tailored treatment approach presented here suggests that, notwithstanding factors complicating care provision which require specific attention, this is feasible.

KEYWORDS: Mental health, asylum seekers, undocumented, treatment, posttraumatic stress disorder, refugees

HIGHLIGHTS

• Mental health and psychosocial problems are highly prevalent among undocumented asylum seekers, but they lack the right care.• Viewed from both a medical-ethical and a human rights perspective, state-of-the-art treatment should be provided.• A proposed treatment model suggests that, notwithstanding complicating factors which require specific attention and attitude, this is feasible. • Collaboration between mental health care providers, social services and governmental parties is a relevant element.

Indocumentados solicitantes de asilo con un transtorno de estrés postraumático en los países bajos

Antecedentes: Hasta la fecha, la mayoría de los estudios sobre la salud mental de los refugiados en Europa se han centrado en la prevalencia y el tratamiento de la psicopatología. Sin embargo, poco se sabe acerca de aquellos que residen ilegalmente en el país que le acoge, en los Países Bajos, en su mayoría referidos como solicitantes de asilo indocumentados. Hay indicios de que la salud mental y los problemas psicosociales son más frecuentes en este grupo, que entre los refugiados en general, con resultados de tratamiento insatisfactorios.

Objetivo: Describir las características y los problemas psicosociales y de salud mental de los solicitantes de asilo indocumentados, y establecer la necesidad y la viabilidad de un enfoque de tratamiento personalizado.

Método: Basado en una revisión de la literatura y una amplia experiencia clínica, se establecen problemas comunes de salud mental y psicosociales y acceso a la atención para solicitantes de asilo indocumentados, así como el enfoque de tratamiento común en los Países Bajos. Se describe un programa de tratamiento a medida y experiencias con su implementación.

Resultados: La salud mental y los problemas psicosociales son muy frecuentes entre los solicitantes de asilo indocumentados, y el acceso a la atención es limitado. Además, el tratamiento en los Países Bajos, si se proporciona, es en su mayoría insuficiente y prolongado. Dados los problemas psicosociales específicos y las condiciones de vida de los solicitantes de asilo indocumentados, un criterio necesario para permitir una provisión de tratamiento adecuada y basada en la evidencia es el reconocimiento de sus necesidades específicas. Un programa de tratamiento a medida como se implementa actualmente en los Países Bajos parece cumplir con este criterio y ser factible bajo ciertas condiciones. La colaboración entre los proveedores de atención de salud mental y el servicio social involucrado y las partes gubernamentales mediante reuniones periódicas, aunque complicadas, es un elemento relevante.

Conclusiones: A pesar de que los solicitantes de asilo indocumentados residen ilegalmente en un país, por ética médica y perspectiva de los derechos humanos, aquellos con problemas de salud mental, requieren un tratamiento adecuado y basado en la evidencia. El enfoque de tratamiento personalizado presentado aquí sugiere que, a pesar de los factores que complican la provisión de atención que requieren atención específica, esto es factible.

Abstract

背景:迄今为止,大多数关于欧洲难民心理健康的研究都集中在精神病理学的流行率和治疗上。然而,很少有人知道非法居住在东道国的人(在荷兰大多被称为无记录寻求庇护者)的情况。有迹象表明,心理健康和心理社会问题在这一群体中比在一般难民中更为普遍,治疗结果也不好。

目的:描述无记录庇护寻求者的特征和心理健康以及心理社会问题,并为其确定量身定制治疗方法的必要性和可行性。

方法:根据文献综述和丰富的临床经验,我们讨论了无记录寻求庇护者共同面临的心理健康问题和心理社会问题,以及在荷兰的护理可及性和普遍治疗方法。我们还描述了一个定制的治疗方案和实施这个方案的体验。

结果:在无记录的寻求庇护者中,心理健康和心理社会问题非常普遍,但获得医疗服务的机会有限。此外,荷兰的治疗(如果提供的话)大多不足但等待期很长。鉴于无记录件寻求庇护者的具体心理社会问题和生活条件,实现充分和循证治疗的必要标准是承认他们的独特需求。目前在荷兰实施的定制治疗方案似乎符合这一标准,并且在某些条件下是可行的。精神卫生保健提供者与参与社会服务和政府各方之间通过定期会议进行合作,这个过程虽然复杂,但却是一个影响因素。

结论:尽管无记录件的寻求庇护者是非法居民,但出于医疗道德和人权观点必须为那些有精神健康问题的人提供充分和循证的治疗。这里提出的定制治疗方法表明,尽管需要特别注意的护理提供复杂化,但这是可行的。

关键词: 心理健康;寻求庇护者;无记录;治疗;创伤后应激障碍;难民

1. Background

1.1. Asylum seekers and refugees

When people flee to another country, formal acceptance of the asylum application by the host country results in a residence permit, which provides legality to the persons’ stay in the country. In the Netherlands, this grants access to the housing and labour market, education, insurances and healthcare. In general, Dutch citizenship may be obtained after five years of legal residence in the country. People seeking asylum in the Netherlands are entitled to receive services such as shelter and basic healthcare pending the asylum procedure. In case of a negative status decision, meaning a formal non-recognition as a refugee, the right to reside in the country gets withdrawn. Asylum seekers are then usually referred to as ‘undocumented’ or ‘illegally residing’.

In spite of the many adverse consequences of illegal residence, persons may prefer to stay in the Netherlands for a variety of reasons. In the case of undocumented asylum seekers (UAS) these may include: persistent fear of violence or persecution in the country of origin; a lack of social bonds or network in the country of origin due to warfare or having left that country many years ago or, for younger persons, having grown up mainly outside the country of origin; having close relatives legally residing in the Netherlands; or not being recognized as a former citizen by the designated country of origin (these last mentioned persons cannot formally be expelled).

As entitlement to basic services and income-generating opportunities are lacking, life is harsh for these undocumented people. Many face ongoing uncertainty about shelter for the night and wander from crowded dormitories in public shelters or couches at friends’ homes to open spots in parks or under bridges. Being undocumented and living on the streets leads to stigmatization and discrimination, the fear of being arrested and expelled, and increased risk of re-victimization. Homeless women particularly run the risk of rape or sexual exploitation. Another negative consequence of illegal status is the lack of income and access to education, which puts persons at higher risk of mental health problems (Lund et al., 2010) or turning to criminal activities (e.g. Raphael & Winter-Ebmer, 2001).

In this paper we argue that this population should be considered a distinct group with specific needs and that, contrary to common practice, trauma-focused psychotherapy can be offered. A treatment approach is outlined, and its feasibility as well as the obstacles are discussed.

1.2. Mental health

While there is ample evidence that the prevalence of mental health problems among refugees is high, studies on UAS are limited. Symptoms of refugees are more severe, comorbidity is more prevalent and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is about 10 times more likely to occur in adult refugees in western countries than in age-matched general populations in host countries. In addition, about 5% are diagnosed with a major depressive disorder (Fazel, Wheeler, & Danesh, 2005). Some studies included in Fazel et al.’s systematic and comprehensive review found relatively high prevalence rates of other disorders, such as psychotic disorders (2%) and generalized anxiety disorder (4%). A PTSD prevalence of 13–25% was found in another systematic review and meta-analysis which included 82,000 refugees in 40 countries (Steel et al., 2009). The absence of a residence status appeared to be one of the significant risk factors for depression, but not for PTSD. These reviews show the extent and diversity of psychopathology among refugees. Kirmayer et al. (2011) and others (Gerritsen et al., 2006; Laban, Komproe, Schreuder, & De Jong, 2004) presented strong evidence for much higher prevalence rates of mental health problems in refugees in various countries of residence in comparison to the general population, regardless of residence status.

In addition to a language barrier, other factors often complicating diagnosis and treatment include patients’ culture-bound presentations, their idioms of distress and explanatory models of experienced problems. These can cause mental health professionals to have difficulties in correctly identifying the patients’ specific problems and in categorizing these in western terms (Hinton & Lewis-Fernández, 2010), as well as in reaching consensus with patients on the support or treatment of choice (Myhrvold & Smastuen, 2017; Teunissen et al., 2015; van Loenen et al., 2017). Diagnostic processes may take more time, diagnoses are often revised along treatment tracks and the focus of treatments may change. In addition, substance abuse and impulse control problems often complicate treatment, and the high incidence of new – often traumatic – life events may lead to symptom reactivation (Schock, Bottche, Rosner, Wenk-Ansohn, & Knaevelsrud, 2016).

The results mentioned refer to refugees in general. One can expect that the difficulties and problems will be worse for those asylum seekers who do not have any status at all, although knowledge about their mental health condition as well as their treatment is limited. There are strong reasons to assume that certain population-specific factors generally complicate treatment for UAS. A sense of powerlessness during post-migration resettlement, which can develop during prolonged uncertainty, can negatively impact depression and other mental health problems (Kirmayer et al., 2011). Kirmayer et al. found elevated rates of depression and chronic pain, and a prevalence rate of posttraumatic stress disorder up to 10 times higher in refugees than in the general population. Uncertainty about immigration or refugee status, unemployment, loss of social status and social exclusion were, among others, important risk factors. These factors apply even more strongly to UAS. An exploratory analysis of psychological distress among UAS in Norway revealed severe distress, which mainly appeared to be related to exploitation, loneliness, powerlessness, fear and constant worry (Myhrvold & Smastuen, 2017). On the basis of in-depth interviews, the authors considered this a stress response due to circumstances reflecting the state of illegal residence.

Laban et al. (2004) provided evidence in a group of Iraqi asylum seekers that a lengthy asylum procedure was an important risk factor for psychiatric problems and was significantly associated with higher rates of symptoms of anxiety, depression and somatoform disorders. This is likely to be the case for UAS, most of whom experience an exceptionally extended period of uncertainty, with repeated appeals during the asylum procedure, ending in great disillusion. This adds to the stress due to critical life events preceding and during the flight, and dire living conditions.

As another mental health consequence of ongoing adversity, UAS frequently display a state of demoralization, which essentially reflects the loss of hope. Studies have indicated associations between demoralization and life-events, poor language proficiency and unemployment (Briggs, 2013; Clarke & Kissane, 2002), all of which are issues UAS are facing. Although it is not considered a mental disorder as such, and its value for clinical diagnosis is debated (Briggs, 2013; Hocking & Sundram, 2015), demoralization is clinically recognized (Tecuta, Tomba, Grandi, & Fava, 2015). Demoralization may arise when a person cannot meet the own or others’ expectations, personal resources have been exhausted, and coping strategies fall short. Feelings of incompetence and failure, helplessness and hopelessness become apparent. Although there are similarities with depression, major differences seem to be the prominence of subjective incompetence in demoralization and anhedonia in depression (Clarke, Kissane, Trauer, & Smith, 2005). Demoralization may have adverse health outcomes (Tecuta et al., 2015), and its hallmark characteristic of hopelessness may lead to suicidal ideation (Clarke & Kissane, 2002). The phenomenon may heavily impact wellbeing and receptiveness to treatment.

1.3. Access to care

For undocumented migrants, access to healthcare is constrained. Several studies regarding refugees in Europe have established constrained access to healthcare, and specific factors for UAS add to this. A qualitative study explored the health needs and experiences of refugees and newly arrived migrants in seven European countries, most of them still being on the move (van Loenen et al., 2017). The refugees in question, a majority being males from Syria and Afghanistan, were confronted with limited access to healthcare and different sorts of barriers towards receiving the right quality of services. Main barriers were formed by time pressure; lack of trust; fear of stigmatization; insufficient information regarding rules, procedures, organization and location of healthcare services; and difficulties in finding their way in the healthcare system. Lack of continuity of care was another important issue, related to problems obtaining medication and to providing or receiving information about other treatments. Language barriers proved to be of interest in all settings that were studied.

A recently conducted systematic review on the use of healthcare services by undocumented migrants in Europe showed a difference between documented and undocumented migrants (Winters, Rechel, de Jong, & Pavlova, 2018). Twenty-nine included studies provided insight in the specific problems undocumented migrants face when trying to receive either physical or mental health care. It showed an underutilization of different types of healthcare services by undocumented migrants, compared to documented migrants. Even if care was received, it was often ineffective. Similar findings were reported in Switzerland (Heeren et al., 2014).

In the Netherlands UAS have a status aparte concerning access to healthcare (Biswas, Toebes, Hjern, Ascher, & Norredam, 2012; Cuadra, 2012). While not being covered by a healthcare insurance, all are entitled to receive basic healthcare, including mental health care. Medical professionals may claim reimbursement from a specific governmental fund, but only 80% of the usual fee is covered for most treatments included. Not all health providers are aware of this possibility. Besides, tight budgets and the need to follow a separate procedure may discourage use of the regulation and openness to treating this patient population. Such conditions create thresholds for medical care provision and for mental health care in particular, given that multiple consultations may be required.

2. Treatment

2.1. Common practice

The psychological treatment of UAS in the Netherlands takes place in regular mental health institutions. Up till now it is common practice to offer mostly supportive treatments to UAS with trauma-related mental health problems (Jongedijk, 2014a). A trauma-focused psychotherapy (referred to as trauma-focused treatment, TFT) is usually not offered, due to unstable living conditions of the target population.

The general opinion among psychotherapists appears to be that circumstances need to be stable before starting TFT. Various authors have argued that, within existing PTSD treatments for complex mental health issues (multiple traumas, comorbidity or other additional problems), effective trauma-focused interventions are being offered insufficiently. Reasons for this include clinicians’ fear for harmful effects of imaginal exposure, such as exacerbation of symptoms and drop-out (Becker, Zayfert, & Anderson, 2004; Foa, Gillihan, & Bryant, 2013; van Minnen, Hendriks, & Olff, 2010). It is also sometimes assumed that asylum seekers and refugees are perceived as too vulnerable and are at higher risk of complex PTSD, both of which might be reasons to deviate from PTSD treatment guidelines suggesting TFT. This assumption has however been disputed. ter Heide et al. conclude that the clinical practice of extensively or solely stabilizing techniques is not scientifically justified, and that complex PTSD is only present in a minority of refugees (ter Heide, Mooren, & Kleber, 2016). They argue there is no reason to postpone TFT for help-seeking refugees with PTSD.

Nevertheless, supportive treatment as usually applied can create a stable psychological balance. This could be considered a survival mode based on symptom management with the aid of a committed clinician. With new stressors arising continuously, such balance is highly vulnerable. Improvement of psychosocial conditions is mostly unlikely in the short term. As described by Jongedijk from clinical practice, clinicians often continuously provide solely ineffective supportive treatment for many years to traumatized UAS (2014a). From these practices, a strong effect on trauma symptoms is not to be expected. Unsuccessful treatment may encourage patients to repeatedly seek help from other mental health care providers. In addition, a feeling of insufficiency may cause professionals themselves to consider referral to colleagues as a good option. In summary, even if UAS are seeking and receiving treatment for trauma-related mental health problems, the applied treatments often are non-comprehensive, barely effective and protracted.

2.2. A specific treatment approach

2.2.1. Rationale

The treatment characteristics and results as described above encouraged involved clinicians in the Netherlands to seek a more targeted and evidence-based approach for UAS. Even though treatment duration should be delineated, any therapeutic process could be expected to be disturbed by authorities responsible for making undocumented persons leave the country. Invitations from the Departure and Repatriation Service (Dienst Terugkeer & Vertrek, DT&V) to come discuss return to the country of origin usually have a highly distressing impact. This adds to already prevailing mental health problems and stressful living conditions, and may result in obstructing patients’ recovery and even in them hiding and dropping out of treatment. DT&V, for their part, acknowledged that mental health problems often hinder UAS to adequately discuss, think about and anticipate their future.

In the city of Amsterdam, the authorities did not succeed in finding a proper response to the situation of undocumented persons with serious health problems. In 2014, various regional social service organizations and mental health care organizations started having monthly intersectoral meetings with the city authorities and public health services, DT&V and the Immigration and Naturalization Service, to try break the deadlock described above. During each meeting, a number of UAS with trauma-related mental health problems would be discussed with the consent of the persons in question. Consensus was sought about possible trajectories for physical and mental health care and sufficient time for this, social support, housing or shelter, and social and legal aid, initially aimed at the persons’ voluntary return to the country of origin.

At the same time, an outpatient clinic started at a mental health care organization in the Amsterdam region in the Netherlands, particularly targeting UAS with a PTSD and related mental health problems. The starting points for its treatment programme were (1) to offer a state-of-the-art, evidence-based TFT, prompted by both a human rights and a medical ethical perspective, (2) a limited duration treatment, for reasons of time-effectiveness and treatment capacity, and to convince involved authorities to not bother patients during treatment, and (3) to regularly discuss patients’ living and social condition and legal perspective during the monthly intersectoral meetings mentioned above, in accordance with public health principles.

During these meetings, as expected, serious ethical dilemmas emerged due to the very different perspectives and objectives of the participating parties. Nonetheless, it became clear that participants were encouraged to look beyond their familiar perspectives and that, in the end, consensus and intersectoral collaboration was possible. Over the first 15 months during which the meetings took place, trajectories were established for 54 traumatized UAS. For 11 of these, legal residence appeared to be a likely option after all. Eight were granted temporary residence for medical reasons, and 19 agreed to accept assistance to prepare for voluntary return to their countries of origin. For 16, the agreed trajectory appeared to be impracticable or was unsuccessful (Arq Psychotrauma Expert Group, 2015).

2.2.2. Outline

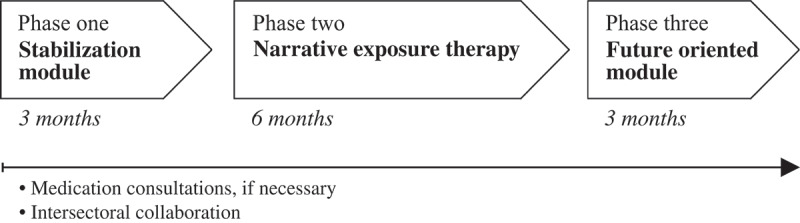

The developed treatment programme is specifically for UAS aged 18–65 years with a primary diagnosis of PTSD (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Treatment duration has been set at one year. Treatment can start at various time points, from shortly to long after a patients’ arrival in the Netherlands, after a long episode of treatment elsewhere or as a first contact in mental health care. Patients are referred to the outpatient clinic by a general practitioner. In addition, treatment is only available to patients living in the Amsterdam region, due to the location of the organization’s collaborating partners in the city, and because travel expenses for consultations are compensated by the organization or other involved parties. Patients from outside the region are, however, welcome for advice or a second opinion. Figure 1 shows the outline of the treatment programme. The treatment programme consists of three phases – stabilization, evidence-based TFT and future orientation – as proposed by others (e.g. Herman, 1992; Mooren & Stöfsel, 2014).

Figure 1:

Overview of one year treatment program

2.2.3. Phase one

First a stabilization phase of three months takes place. Care provided within PTSD treatment approaches under the heading of ‘stabilization’ is diverse, and mostly aimed at teaching self-regulation strategies and/or starting a drug regimen. The need for such care as preparation for TFT has become the subject of considerable debate (e.g. De Jongh et al., 2016). Some advocate an immediate start of TFT (e.g. Bicanic, De Jongh, & Ten Broeke, 2015), while others consider stabilization instrumental in ensuring that individuals better tolerate TFT and to prevent dropout.

There are reasons to include a preparatory phase prior to TFT in the treatment of UAS, albeit within a limited timeframe. Clinical experience of the practitioners involved in this study had shown that distrust, preoccupation with current social problems, and limited cognitive availability due to severe symptoms in patients usually ruled out an immediate start of TFT. Prior effort, aimed at gaining trust, openness, familiarity with and commitment to treatment, proved to be necessary in inhibiting no-show or drop-out and to introduce medication when needed. During this phase a decrease of PTSD symptoms would not be expected (Beldman & Kessels, 2017).

The stabilization module is designed for group sessions, with a maximum of 10 participants, or applied individually. The latter is often the case because of language differences. Individual consultations by a physician are provided if necessary. The composition of groups is based on language. Over three months, weekly sessions of 90 minutes take place. In exceptional circumstances, patients can be offered a shortened track if coping skills and relevant knowledge are already present. A treatment guide designed for this phase integrates different methods (Cloitre et al., 2011; Dorrepaal, Thomaes, & Draaier, 2009) with clinical insights. This guide serves as a framework, as the relevance of addressing all items is prioritized over their order and specific approach.

The main objectives of the module are to provide psychoeducation, to create an opportunity to experience group support and the value of sharing, to teach coping skills and to increase mastery. During the module, a sociogram and a personal crisis plan are documented by all participants in their workbooks. This output can be seen as a condition for entering the following treatment phase.

The first session consists of personal introductions, an explanation of the goals, the setting of group rules and an introductory game. Subjects addressed over the following sessions are psychoeducation regarding PTSD; the relation between symptoms and experienced trauma; recognizing various emotions; the interplay between behaviour, thoughts and feelings; balancing between burden and capacity; grounding and concentration; self-care (sleeping hygiene; coping with nightmares; healthy physical activity, food and drinks; use of substances; setting personal limits; and standing up for your rights). During the last session TFT, in particular Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET), is introduced and explained.

During this phase, there may be an unintentional shift in focus from the actual objectives to individual problems caused by prevailing social circumstances. It is up to the clinicians to monitor this closely; working with co-counsellors may help to prevent this.

2.2.4. Phase two

In a second phase, treatment goals are a reduction of posttraumatic stress symptoms and an improvement of the quality of life. TFT is offered through NET. There is a variety of TFTs with proven effectiveness, including Trauma-focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, Prolonged Exposure, Cognitive Processing Therapy, Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, and Brief Eclectic Psychotherapy for PTSD. The choice of NET is mainly based on the fact that its evidence specifically has been established in refugees with multiple traumas in non-stable circumstances (Bichescu, Neuner, Schauer, & Elbert, 2007; Neuner et al., 2008; Neuner, Schauer, Klaschik, Karunakara, & Elbert, 2004; Robjant & Fazel, 2010). A systematic review of studies on trauma treatments for adult refugees showed that NET is among the treatments with the best documentation of effect in terms of overall study quality and accumulation of evidence (Palic & Elklit, 2011). A review of NET for populations in relatively unstable circumstances, like refugee camps and asylum seeker centres, shows significant improvement of PTSD symptoms, mostly six months after treatment (Robjant & Fazel, 2010). Studies on the effectiveness of NET yielded effect sizes ranging from 0.53 (professionals) to 1.02 (locally trained refugee counsellors), with a total average of 0.63 (medium) (Gwozdziewycz & Mehl-Madrona, 2013). Various aspects of NET are being debated (e.g. Catani et al., 2009; Fernando, 2014; Mundt, Wünsche, Heinz, & Pross, 2014; Schaal, Elbert, & Neuner, 2009), including its short duration, i.e. eight sessions in the first trials, which might be too little to address more complex PTSD originating from serial or long-term exposure to trauma (Mundt et al., 2014). The discussion also concerns the long period before treatment effects become manifest, as well as the select group of NET researchers (often also the designers of the method).

NET has been developed by a group of clinicians and researchers from Konstanz, Germany. The method can be traced back to Testimony Therapy, first described in Chile (Cienfuegos & Monelli, 1983), and regular imaginal exposure therapy, particularly designed for treating survivors of torture and war. The often multiple traumatic events are processed with use of a lifeline, physically constructed in the first session by placing flowers symbolizing good events and stones representing traumatic events along a rope stretched on the floor or a table. Over the following sessions, therapist and patient review all events in chronological order from birth to present. Imaginal exposure is applied for each traumatic experience. The idea is to connect the declarative ‘cold’ memory, which contains contextualized information, with the non-declarative ‘hot’ memory, including detailed sensory information and cognitive and emotional perceptions. The autobiographical memory has been disrupted by traumas. By integrating more contextual information into the ‘hot’ memory, a consistent chronological account of events can be made, resulting in a complete life narrative. The fear structure is gradually inhibited and PTSD symptoms decrease. (For detailed information about its development and rationale, see Jongedijk, 2014a, 2014b; Neuner, Schauer, Roth, & Elbert, 2002; Neuner et al., 2004, 2008.)

Although in its original design NET consisted of only eight sessions, an average duration of six months with weekly sessions is pursued within the framework of the treatment programme presented here. This longer treatment period relates to the extensive trauma histories of most patients and the many social stressors interfering with TFT, resulting in periods of limited emotional availability, commitment and no-show.

2.2.5. Phase three

Phase three is a future oriented module lasting three months. In this treatment component, the patient is invited to focus on future perspectives and helped to make life choices. Like phase one, the module is designed for group sessions with group composition based on language, but can be applied individually. The main goals are to create awareness of the participant’s own existing agency and empowerment, as well as to help find identity and values, which can open up the mind to consider options for the future. The module is composed of various elements of other recovery oriented methods (Arredondo & Mampaey, 2012; Geraci, 2011; van Grondelle, 2008; Harris, 2010; Sterk, 2015).

First, there is a meeting of the patient, a clinician, and an external provider of juridical counselling. The main objective is to clarify to the patient if chances of receiving a residence permit are valued nil, so they can rethink other options more easily. In the first group session, patients receive a workbook which, as an output at the end of the module, will consist of four documents: a personal compass of values; a circle of the own identity; an overview of individually felt pros and cons of possible future pathways; and an overview of ‘identity-circles’ within the various future options. Subjects addressed during the sessions are: acceptance of residual symptoms; personal values; coping strategies; acceptance and values around difficult situations; and the own identity. Finally, five future pathways or options are outlined: receiving a residence permit; continuing illegal residence in the Netherlands; returning to the country of origin; migrating to another country; or other options possibly raised by participants. Clinicians explicitly do not take a stand here. Rights and obligations of an undocumented person are discussed, and stigmas around illegality and the impact on identity are elaborated. The last session is devoted to looking back, looking forward, and saying farewell. After this module, a choice is made for each participant, between termination of treatment or referral if necessary.

Offering a module like this requires broadening the treatment focus and responsibility beyond psychological issues or psychiatric disturbance. While for some professionals this may not come naturally when treating UAS, the need to address the social dimension is clear.

3. Discussion

During the first period of implementation, the treatment programme was confronted with various challenges. A combination of organizational, financial and political factors led to an increase of waiting time between the three treatment phases. At an individual level, treatment progress was impacted by stressors UAS are exposed to in daily life. Examples included forced change of shelter, immigration detention, change in juridical status (from deportation or a procedure started, to receiving a residence permit), pregnancy, and also interfering comorbidity like substance abuse. Since patients’ prevailing social problems often relate to basic life needs, they inevitably necessitate for clinicians’ attention, but at the same time disturb working as per protocol. Treatment may be interrupted more than once when consecutive life events occur.

Clearly, while patients do want and need treatment, current social adversities can make them realize that continuing in treatment is only possible when these stressors are properly addressed. Therefore, patients may be less able to be emotionally available or committed to engaging in treatment. Clinicians should try to make a clear distinction in practical issues, which could be dealt with, for instance by a social worker or a lawyer, outside the TFT setting, or issues that limit emotional availability in a non-functional manner, such as worrying, in which the clinician can help the patient using the skills that they are learning in treatment, such as cognitive reappraisal, emotion regulation and reflective processing, to effectively deal with those stressors. This will enable the patient to resume TFT with an increased sense of self-confidence and trust in the therapy.

In addition, there are organizational problems typically related to services for the group of UAS. Budget cuts, involving all mental health institutions in the Netherlands, disproportionately affect the programme for UAS, partly because deficient cost coverage (see above) limits the organization’s financial capacity. Another issue is the great personal engagement clinicians treating UAS sometimes display, which may involve an experience of powerlessness and the risk of demoralization – which again, as a parallel process, may reflect patients’ emotional state. A shorter duration of involvement in treating UAS may be a solution, but induces high turnover of personnel. The need to discuss social problems, such as a lack of shelter, in the psychiatric treatment of UAS may seem debatable to many professionals. Either way, clinical practice shows one can hardly deny that social problems complicate treatment. Yet, if these are present, it requires flexibility and persistence of the clinician to be able to continue trauma-focused treatment.

It is important to realize that, for patients, the clarity and structure of the programme constitutes a supportive and essential contrast with the insecurities of daily life. To be acknowledged as an individual and taken seriously is of prime importance. Clinicians too may, when confronted with powerlessness themselves, draw strength from the structure of the programme and the possibility of providing evidence-based TFT. The conviction of meeting medical-ethical standards and trying to establish significant change creates professional and ideological satisfaction.

The treatment centre took part in the city’s intersectoral collaboration, essential to the programme’s set-up. Clinicians appreciated being included in an innovative mental health care initiative, as this created mutual understanding, but, at the same time, it posed the ethical issue which patient-related information to share. Prior consultation with national health authorities about the nature of collaboration, and explicit written consent per patient, helped determine which information could be raised and could be expected to be in support of patients.

3.1. Research

An uncontrolled trial is currently being conducted, aiming first to establish the feasibility of the treatment model and, furthermore, identify changes in patients’ psychiatric symptom profiles, including PTSD symptom severity and quality of life, through assessments between all phases, over the full year of treatment and at follow-up. In order to represent the population of UAS and the treatment sufficient, no exclusion criteria have been set. Lifetime exposure to possibly traumatic events will be established as well. Inclusion started in July 2016. Assessments were conducted by use of the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS), the Life Event Scale (LEC), the Cantril’s Ladder of Life (CLL) and the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI). The number of participants recruited so far is approximately 50.

4. Conclusion

UAS have frequently experienced multiple adverse events or traumas, and current life in challenging social circumstances is also extremely stressful. Prevalence rates for (comorbid) mental health problems are high. UAS can be considered as a distinct population with unique mental health and psychosocial needs. Viewed from both a medical-ethical and a human rights perspective, state-of-the-art treatment should be provided to UAS.

There are barriers in access to healthcare. Both financial considerations and the expectation of limited treatment success discourage the provision of mental health services among treatment centres and clinicians. If provided at all, treatment is mostly non-comprehensive but prolonged. This study describes a one year treatment programme consisting of stabilization, evidence-based TFT and a future oriented module, combined with intersectoral collaboration between involved social service and governmental parties. The treatment programme appears to be feasible, provided that factors complicating treatment proceedings require a specific attitude among clinicians. An observational study on changes in patients’ symptom profiles over time and quality of lives during and after treatment will follow and may provide data regarding potential effectiveness. The current study is relevant for decision-making around mental health care provision to UAS for clinicians, European policy makers and healthcare organizations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rina Ghafoerkhan, Jetske van Heemstra, Evelyn Kaizer, Anneke Jansma and Linda Spanjaards for their contribution in designing the treatment programme studied.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., Text Revision). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Arq Psychotrauma Expert Group (2015). Casuïstiekoverleg Ongedocumenteerden met Psychiatrische Problematiek in Amsterdam COPPA Pilot februari 2014 – Juni 2015 (Internal report. Unpublished). [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo M., & Mampaey S. (2012). Toekomstoriëntering aan mensen zonder wettig verblijf. Borgerhoit: Antwerps Integratiecentrum de8. [Google Scholar]

- Becker C. B., Zayfert C., & Anderson E. (2004). A survey of psychologists’ attitudes towards and utilization of exposure therapy for PTSD. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42(3), 277–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beldman G., & Kessels H. (2017). The effect of a short-term group stabilisation training in patients with complex posttraumatic stress disorder. Tijdschrift voor psychiatrie, 59(11), 672–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicanic I., De Jongh A., & Ten Broeke E. (2015). Stabilisation in trauma treatment: Necessity or myth? Tijdschrift voor psychiatrie, 57(5), 332–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichescu D., Neuner F., Schauer M., & Elbert T. (2007). Narrative exposure therapy for political imprisonment-related chronic posttraumatic stress disorder and depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(9), 2212–2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas D., Toebes B., Hjern A., Ascher H., & Norredam M. (2012). Access to health care for undocumented migrants from a human rights perspective: A comparative study of Denmark, Sweden, and The Netherlands. Health and Human Rights, 14(2), 49–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs L. (2013). Is the degree of demoralization found among refugee and migrant populations a social-political problem or a psychological one? The European Journal of Psychiatry, 27(1), 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Catani C., Kohiladevy M., Ruf M., Schauer E., Elbert T., & Neuner F. (2009). Treating children traumatized by war and Tsunami: A comparison between exposure therapy and meditation-relaxation in North-East Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry, 9(1), 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cienfuegos A. J., & Monelli C. (1983). The testimony of political repression as a therapeutic instrument. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 53(1), 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke D. M., & Kissane D. W. (2002). Demoralization: Its phenomenology and importance. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(6), 733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke D. M., Kissane D. W., Trauer T., & Smith G. C. (2005). Demoralization, anhedonia and grief in patients with severe physical illness. World psychiatry: Official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 4(2), 96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M., Courtois C. A., Charuvastra A., Carapezza R., Stolbach B. C., & Green B. L. (2011). Treatment of complex PTSD: Results of the ISTSS expert clinician survey on best practices. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24(6), 615–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadra C. B. (2012). Right of access to health care for undocumented migrants in EU: A comparative study of national policies. European Journal of Public Health, 22(2), 267–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jongh A., Resick P. A., Zoellner L. A., Van Minnen A., Lee C. W., Monson C. M., … Feeny N. (2016). Critical analysis of the current treatment guidelines for complex PTSD in adults. Depression and Anxiety, 33(5), 359–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrepaal E., Thomaes K., & Draaier N. (2009). Vroeger en verder. Amsterdam: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Fazel M., Wheeler J., & Danesh J. (2005). Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: A systematic review. The Lancet, 365(9467), 1309–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando G. A. (2014). Do we really have enough evidence on Narrative Exposure Therapy to scale it up? Intervention, 12(2), 283–286. [Google Scholar]

- Foa E. B., Gillihan S. J., & Bryant R. A. (2013). Challenges and successes in dissemination of evidence-based treatments for posttraumatic stress: Lessons learned from prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(2), 65–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraci D. (2011). Bewogen terugkeer: methodiek voor psychosociale begeleiding van (ex)asielzoekers en ongedocumenteerden. Utrecht: Pharos. [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen A. A., Bramsen I., Devillé W., Van Willigen L. H., Hovens J. E., & Van Der Ploeg H. M. (2006). Physical and mental health of Afghan, Iranian and Somali asylum seekers and refugees living in the Netherlands. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41(1), 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwozdziewycz N., & Mehl-Madrona L. (2013). Meta-Analysis of the Use of Narrative Exposure Therapy for the Effects of Trauma Among Refugee Populations. The Permanente Journal, 17(1), 70–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R. (2010). Acceptatie en commitment therapie in de praktijk. Amsterdam: Hogrefe Uitgevers. [Google Scholar]

- Heeren M., Wittmann L., Ehlert U., Schnyder U., Maier T., & Muller J. (2014). Psychopathology and resident status - comparing asylum seekers, refugees, illegal migrants, labor migrants, and residents. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(4), 818–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman J. L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 377–391. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton D. E., & Lewis-Fernández R. (2010). Idioms of Distress Among Trauma Survivors: Subtypes and Clinical Utility. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 34(2), 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocking D., & Sundram S. (2015). Demoralisation syndrome does not explain the psychological profile of community-based asylum-seekers. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 63, 55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongedijk R. A. (2014a). Levensverhalen en psychotrauma. Narratieve Exposure Therapie in theorie en praktijk [Life stories and psychotrauma. Narrative exposure therapy in theory and practice] Amsterdam: Boom. [Google Scholar]

- Jongedijk R. A. (2014b). Narrative exposure therapy: An evidence-based treatment for multiple and complex trauma. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 26522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer L. J., Narasiah L., Munoz M., Rashid M., Ryder A. G., Guzder J., … Pottie K. (2011). Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: General approach in primary care. Canadian Medical Association journal, 183(12), E959–E967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laban C. J., Komproe I. H., Schreuder B. A., & De Jong J. T. V. M. (2004). Impact of a long asylum procedure on the Prevalence of psychiatric disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Dizease, 192. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000146739.26187.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund C., Breen A., Flisher A. J., Kakuma R., Corrigall J., Joska J. A., … Patel V. (2010). Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 71(3), 517–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooren T., & Stöfsel M. (2014). Diagnosing and treating complex trauma. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mundt A. P., Wünsche P., Heinz A., & Pross C. (2014). Evaluating interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder in low and middle income countries: Narrative Exposure Therapy. Intervention, 12(2), 250–266. [Google Scholar]

- Myhrvold T., & Smastuen M. C. (2017). The mental healthcare needs of undocumented migrants: An exploratory analysis of psychological distress and living conditions among undocumented migrants in Norway. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(5–6), 825–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuner F., Onyut P. L., Ertl V., Odenwald M., Schauer E., & Elbert T. (2008). Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder by trained lay counselors in an African refugee settlement: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(4), 686–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuner F., Schauer M., Klaschik C., Karunakara U., & Elbert T. (2004). A comparison of narrative exposure therapy, supportive counseling, and psychoeducation for treating posttraumatic stress disorder in an african refugee settlement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(4), 579–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuner F., Schauer M., Roth W., & Elbert T. (2002). Testimony therapy as an acute intervention in a macedonian refugee camp: Two case reports. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 30, 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Palic S., & Elklit A. (2011). Psychosocial treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in adult refugees: A systematic review of prospective treatment outcome studies and a critique. Journal of Affective Disorders, 131(1–3), 8–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raphael S., & Winter-Ebmer R. (2001). Identifying the effect of unemployment on crime. The Journal of Law and Economics, 44(1), 259–283. [Google Scholar]

- Robjant K., & Fazel M. (2010). The emerging evidence for Narrative Exposure Therapy: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(8), 1030–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaal S., Elbert T., & Neuner F. (2009). Narrative exposure therapy versus interpersonal psychotherapy. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78(5), 298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schock K., Bottche M., Rosner R., Wenk-Ansohn M., & Knaevelsrud C. (2016). Impact of new traumatic or stressful life events on pre-existing PTSD in traumatized refugees: Results of a longitudinal study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7, 32106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel Z., Chey T., Silove D., Marnane C., Bryant R. A., & van Ommeren M. (2009). Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association, 302(5), 537–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterk P. (2015). Mind-spring. Methodiek handboek voor trainers. Version March 2015. Retrieved from www.mind-spring.org

- Tecuta L., Tomba E., Grandi S., & Fava G. (2015). Demoralization: A systematic review on its clinical characterization. Psychological Medicine, 45(4), 673–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ter Heide F. J. J., Mooren T. M., & Kleber R. J. (2016). Complex PTSD and phased treatment in refugees: A debate piece. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7, 28687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teunissen E., Van Bavel E., Van Den Driessen Mareeuw F., Macfarlane A., Van Weel-Baumgarten E., Van Den Muijsenbergh M., & Van Weel C. (2015). Mental health problems of undocumented migrants in the Netherlands: A qualitative exploration of recognition, recording, and treatment by general practitioners. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 33(2), 82–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Grondelle N. J. (2008). Tip Methodiek Methodiekbeschrijving ‘Coachen in toekomstgesprekken‘. Utrecht: Pharos. [Google Scholar]

- van Loenen T., van Den Muijsenbergh M., Hofmeester M., Dowrick C., van Ginneken N., Mechili E. A., … Pavlic D. R. (2017). Primary care for refugees and newly arrived migrants in Europe: A qualitative study on health needs, barriers and wishes. The European Journal of Public Health, 28(1), 82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Minnen A., Hendriks L., & Olff M. (2010). When do trauma experts choose exposure therapy for PTSD patients? A controlled study of therapist and patient factors. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(4), 312–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters M., Rechel B., de Jong L., & Pavlova M. (2018). A systematic review on the use of healthcare services by undocumented migrants in Europe. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]