Key Points

Question

Is the extent to which alcohol and other drugs are used in an individual’s birth cohort associated with an individual’s risk of commencing drug use, transitioning to problematic use, and entering remission?

Findings

This study of cross-national data of 90 027 respondents from the World Mental Health Surveys found that an individual’s personal risk of transitioning to greater involvement with drug use is associated with the substance use histories of their age cohort, as well as their own history of involvement with drugs and alcohol. Results were statistically significant after controlling for sociodemographic factors and were consistent across country income levels.

Meaning

Per this analysis, any intervention to reduce substance use within a cohort may also reduce individual-level risk for transitioning into greater levels of involvement with drug use.

This multicountry study examines the association of the drug and alcohol use of an age cohort and the risk of an individual within that age cohort developing drug use, abuse, dependence, and remission from abuse and dependence.

Abstract

Importance

Limited empirical research has examined the extent to which cohort-level prevalence of substance use is associated with the onset of drug use and transitioning into greater involvement with drug use.

Objective

To use cross-national data to examine time-space variation in cohort-level drug use to assess its associations with onset and transitions across stages of drug use, abuse, dependence, and remission.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys carried out cross-sectional general population surveys in 25 countries using a consistent research protocol and assessment instrument. Adults from representative household samples were interviewed face-to-face in the community in relation to drug use disorders. The surveys were conducted between 2001 and 2015. Data analysis was performed from July 2017 to July 2018.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Data on timing of onset of lifetime drug use, DSM-IV drug use disorders, and remission from these disorders was assessed using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Associations of cohort-level alcohol prevalence and drug use prevalence were examined as factors associated with these transitions.

Results

Among the 90 027 respondents (48.1% [SE, 0.2%] men; mean [SE] age, 42.1 [0.1] years), 1 in 4 (24.8% [SE, 0.2%]) reported either illicit drug use or extramedical use of prescription drugs at some point in their lifetime, but with substantial time-space variation in this prevalence. Among users, 9.1% (SE, 0.2%) met lifetime criteria for abuse, and 5.0% (SE, 0.2%) met criteria for dependence. Individuals who used 2 or more drugs had an increased risk of both abuse (odds ratio, 5.17 [95% CI, 4.66-5.73]; P < .001) and dependence (odds ratio, 5.99 [95% CI, 5.02-7.16]; P < .001) and reduced probability of remission from abuse (odds ratio, 0.86 [95% CI, 0.76-0.98]; P = .02). Birth cohort prevalence of drug use was also significantly associated with both initiation and illicit drug use transitions; for example, after controlling for individuals’ experience of substance use and demographics, for each additional 10% of an individual’s cohort using alcohol, a person’s odds of initiating drug use increased by 28% (odds ratio, 1.28 [95% CI, 1.26-1.31]). Each 10% increase in a cohort’s use of drug increased individual risk by 12% (1.12 [95% CI, 1.11-1.14]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Birth cohort substance use is associated with drug use involvement beyond the outcomes of individual histories of alcohol and other drug use. This has important implications for understanding pathways into and out of problematic drug use.

Introduction

Improved understanding of determinants of drug use disorders (DUDs) and transitions through different levels of involvement is important to assist in identifying critical periods when specific interventions may be best targeted and shed light on potential factors that may affect such trajectories. Research on trajectories of drug use has most often considered the transition between use and dependence1,2 or focused on specific populations, such as people in treatment for DUDs.3,4,5

The general population studies that have explored the natural history of substance use show that social contextual risk factors have differential roles in each transition stage.2,6,7,8,9,10 For example, substance use is linked to social and peer-level variables11; and evidence suggests that the extent to which behavior is normative may be associated with adverse substance use outcomes (with people engaging in less normative behavior having a greater likelihood of problematic substance use).12,13

Previous studies have found that chronological age, historical period, and birth cohort effects are associated with differences in substance use and associated problems.14,15,16,17 Differences by age group in substance use and associated problems have often been attributed at least in part to developmental and maturational factors,11 especially when cross-sectional comparisons are made between age groups within a sample of a population that covers a broad age range.18,19,20

However, individuals are also strongly influenced by the broader social context in which they live. Substance use influences (eg, substance use norms, enforcement of sanctions against drug use, drug availability, and perceptions of risk), have varied widely across geographical locations and in different periods in history. Cohort effects include the shared social and environmental influences on individuals born at particular times as they mature, experiencing the extant period effects, including changes in period effects over time. There are complex issues involved in distinguishing period and cohort effects,21,22 and although there is evidence of both influences, research has shown that substance use behaviors are especially associated with cohort effects,17,23,24 which may modify period effects and perhaps have other social influences. Supporting this possibility, we previously used a national study of Australian adults to investigate associations of levels of involvement with alcohol and cannabis use with birth cohort use25 and found that the level of alcohol or cannabis use within an individual’s age cohort was associated with risks of progressing further into involvement with alcohol and cannabis use, respectively.25

In this article, we present (for the first time, to our knowledge) country-level data on lifetime prevalence of illicit drug use, DSM-IV DUDs (including drug abuse and dependence), and remission from DUDs. We also conduct the first-ever analyses of the influence of cohort effects on individuals’ drug use cross-nationally using the World Health Organization (WHO) World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys (https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/),26 a unique database made up of 27 population surveys conducted in 25 countries across the globe. We examine the extent to which an individual’s birth cohort’s use of both alcohol and drugs at various points in the life course is associated with the individual transitioning across levels of involvement with drug use net of the outcomes of the individual’s own history of substance use at that point in time.

Method

Sample

Data come from 27 WMH surveys that assessed DUDs. Six surveys were conducted in countries classified by the World Bank at time of data collection as having low or lower-middle income levels (Colombia [national], Iraq, Nigeria, People’s Republic of China, Peru, and Ukraine), 6 surveys in 6 countries classified as having upper-middle income levels (Brazil, Bulgaria, Colombia [Medellín region only], Lebanon, Mexico, and South Africa), and 15 surveys in 14 in countries classified as having high income levels (Argentina, Australia, Belgium, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Poland, Spain [including separate national and regional surveys], and the United States). Most surveys were based on nationally representative household samples. The sample characteristics for all participating surveys are shown in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Informed consent was obtained before beginning interviews in all countries. Procedures for obtaining informed consent and protecting participants were approved and monitored by the institutional review boards of organizations coordinating surveys in each country. Full details of the WMH surveys have been published previously26,27,28,29,30 and are summarized in the eMethods in the Supplement (which also references eTables 14 and 15 in the Supplement).

Data Analysis

Age at onset and speed of transition between various drug stages were examined. These stages were use (the first time using any drug), DSM-IV abuse, DSM-IV dependence, remission from abuse without dependence (defined as absence of all abuse symptoms for more than 12 months at the time of the interview), and remission from dependence (defined as an absence of all dependence symptoms for more than 12 months at the time of the interview). To improve cross-national comparability, all survey data were restricted to persons 18 years and older at the time of the interview.

All analyses were carried out in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) using weighted data and accounting for the complex survey design features, namely stratification and clustering. Person weights were used to adjust for probability of selection, nonresponse and poststratification factors, and part II data weights adjusted for oversampling of part I respondents with mental disorders. These weighting procedures ensured that all samples are representative of the population of the survey country or region at the time of data collection.

Life-table (actuarial) estimates of the survival functions for age at onset and remission were produced using the SAS PROC LIFETEST procedure and are reported as weighted prevalence. Discrete-time logistic regression models were used to investigate the outcome of cohort and individual substance use variables on the commencement of illicit drug use and transitions from use to disorder (abuse and dependence) and disorder to remission (among participants with a valid age at onset of remission; eMethods in the Supplement). These analyses were conducted in SAS PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC using person-year as the unit of analysis and a logistic link function.

Person-year data sets were created in which each year in the life of each respondent during which they were at risk of transitioning, from the age at onset of the initial stage up to the age at onset of the transition or age at interview (whichever came first), was treated as a separate observational record. The year of transition was coded 1 and earlier years coded 0 on a dichotomous response variable. Survival coefficients and standard errors are presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs. Multivariable significance tests were made with Wald χ2 tests using Taylor series design–based coefficient variance-covariance matrices and significance evaluated at .05 with 2-sided tests.

A country-specific or region-specific contextual variable representing cumulative lifetime prevalence of substance use in the individual’s birth cohort at each year of life was constructed and used to assess transitioning to each drug stage. An individual’s birth cohort was based on their year of birth ±5 years, which created 11-year-wide survey-specific cohorts centered around their year of birth. The cohort widths were reduced for those aged between 18 and 22 years as close as possible to ensure symmetry around birth year; the total band width size was 2 years for 18-year-olds (18-19 years), 3 years for 19-year-olds (18-20 years), 5 years for 20-year-olds (18-22 years), 7 years for 21-year-olds (18-24 years) and 9 years for 22-year-olds (18-26 years). Cohorts were topcoded for those 65 years or older. The independent variable was the estimated proportion (divided by 10) of people in the individual’s birth cohort who had used the specific substance (either alcohol or drugs) as of each prior year of age; in this way, it captured the percentage of people in the cohort who had already commenced use at any given age. To capture only the most prominent changes in cohort use, cohort use prevalence was set to 0 for person years younger than 12 years and topcoded for those 30 years and older. Linearity of the cohort use variables were investigated.

To investigate the outcome of the individual’s own prior involvement with alcohol on risk of drug transitions, 4 mutually exclusive, time-varying dummy variables were included as factors for highest lifetime-to-date level of alcohol involvement (none vs either use, abuse, dependence, or remission from abuse or dependence). In addition, models for transitions after first use considered the types of drugs being used, with indicators for onset of cannabis, cocaine, and other drug use (prescription drugs combined with the category “other drugs” owing to small numbers) as well as whether 2 or more of these drug categories had been used. A total of 6 models investigating cohort and individual substance involvement were investigated: (1) prevalence of cohort drug use, (2) prevalence of cohort alcohol use, (3) individuals’ level of alcohol involvement, (4) type of drugs, (5) number of drugs, and (6) all cohort and individual substance variables. All models adjusted for a wide range of variables (eMethods in the Supplement). Data analysis was performed from July 2017 to July 2018.

Results

Combining participants from all 27 surveys, 90 093 respondents were administered the drug module. Sixty-six respondents (35 from Israel, 15 from Mexico, 11 from Japan, and 5 from South Africa) provided no valid answers to any drug use question and were excluded. Therefore, a total of 90 027 respondents are included in the analyses.

Prevalence of Use, Abuse, Dependence, Use Disorders, and Remission

Lifetime prevalence estimates for use of any drug and specific drugs are shown in Table 1. Across countries, 24.8% (SE, 0.2%) of respondents reported lifetime illicit drug use or extramedical use of prescription drugs. Within each country income grouping, cannabis was the most commonly used drug of those considered; the United States (42.3% [SE, 1.0%]) and New Zealand (41.9% [SE, 0.7%]) had the highest lifetime cannabis prevalence. The United States (16.2% [SE, 0.6%]) and Murcia (Spain, 7.8% [SE, 1.1%]) had the highest lifetime prevalence of cocaine use. Highest estimates of extramedical prescription drug use were observed in some countries in Europe, including Italy (66.0% [SE, 0.2%]), Germany (62.3% [SE, 2.5%]), Spain (61.5% [SE, 2.6%]), Belgium (43.5% [SE, 3.0%]), and France (43.4% [SE, 2.0%]), whereas Iraq (1.3% [SE, 0.2%]), China (5.9% [SE, 0.9%]), Lebanon (6.2% [SE, 1.1%]), Japan (7.0% [SE, 0.8%]), and Bulgaria (7.3% [SE, 0.8%]) had the lowest rates of any drug use.

Table 1. Lifetime Prevalence of Overall Drug Use and Specific Drug Use in the World Mental Health Surveys.

| Countrya | No.b | % (SE)c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannabis | Cocaine | Prescription Drugsd | Other Drugs | Any Drugse,f | ||

| Low and lower-middle income | 18 179 | 5.3 (0.2) | 2.0 (0.1) | 4.7 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.1) | 10.0 (0.3) |

| Colombia | 4426 | 10.8 (0.6) | 4.0 (0.4) | 2.2 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.2) | 12.7 (0.7) |

| Iraq | 4332 | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 1.2 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.0) | 1.3 (0.2) |

| Nigeria | 2143 | 2.7 (0.5) | 0.1 (0.1) | 18.7 (1.3) | 0.5 (0.2) | 20.4 (1.3) |

| Peru | 3930 | 7.9 (0.4) | 4.8 (0.2) | 4.3 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.1) | 13.3 (0.5) |

| China | 1628 | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.0 (0.0) | 5.8 (0.9) | 0.2 (0.2) | 5.9 (0.9) |

| Ukraine | 1720 | 6.4 (1.0) | 0.1 (0.0) | 2.4 (0.6) | 0.8 (0.2) | 8.4 (1.2) |

| Upper-middle income | 20 051 | 9.2 (0.3) | 3.1 (0.2) | 7.8 (0.4) | 1.5 (0.1) | 16.2 (0.5) |

| Brazil | 5037 | 11.8 (0.7) | 5.2 (0.4) | 6.9 (0.3) | 2.5 (0.3) | 17.6 (0.7) |

| Bulgaria | 2233 | 1.3 (0.5) | 0.0 (0.0) | 6.1 (0.6) | 0.0 (0.0) | 7.3 (0.8) |

| Lebanon | 1031 | 4.6 (0.9) | 0.7 (0.3) | 2.0 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.2) | 6.2 (1.1) |

| Medellín | 1673 | 21.9 (1.9) | 6.3 (0.9) | 2.7 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.4) | 22.7 (1.9) |

| Mexico | 5767 | 7.8 (0.5) | 4.0 (0.4) | 1.8 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.2) | 10.1 (0.5) |

| South Africa | 4310 | 8.4 (0.6) | 0.7 (0.3) | 21.5 (1.5) | 1.7 (0.3) | 27.2 (1.7) |

| High income | 51 797 | 24 (0.3) | 4.4 (0.1) | 13.6 (0.2) | 6.2 (0.2) | 33.3 (0.3) |

| Argentina | 2116 | 14.2 (1.0) | 5.8 (0.6) | 14.4 (1.1) | 3.3 (0.5) | 26.3 (1.3) |

| Australia | 8463 | 19.8 (0.6) | 2.9 (0.3) | 2.5 (0.2) | 7.3 (0.4) | 21.4 (0.6) |

| Belgium | 1043 | 10.4 (1.6) | 1.5 (0.6) | 43.5 (3.0) | 2.8 (0.8) | 47.6 (2.8) |

| France | 1436 | 19 (1.6) | 1.5 (0.4) | 43.4 (2.0) | 4.8 (0.7) | 52.7 (1.7) |

| Germany | 1323 | 17.5 (1.6) | 1.9 (0.5) | 62.3 (2.5) | 3.4 (0.7) | 66.4 (2.5) |

| Israel | 4824 | 11.5 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.2) | 12.9 (0.5) |

| Italy | 1779 | 6.6 (0.8) | 1.0 (0.3) | 66.0 (2.0) | 0.9 (0.2) | 66.8 (2.0) |

| Japan | 1671 | 1.5 (0.4) | 0.5 (0.2) | 4.8 (0.7) | 1.8 (0.5) | 7.0 (0.8) |

| Murcia, Spain | 1459 | 23.1 (1.3) | 7.8 (1.1) | 0.9 (0.5) | 3.1 (0.8) | 24.2 (1.5) |

| Netherlands | 1094 | 19.8 (1.3) | 1.9 (0.2) | 20.1 (2.4) | 4.1 (0.8) | 35.9 (2.4) |

| New Zealand | 12 790 | 41.9 (0.7) | 4.3 (0.3) | 6.6 (0.3) | 10.2 (0.4) | 42.9 (0.7) |

| Northern Ireland | 1986 | 17.3 (1.1) | 3.5 (0.5) | 2.3 (0.4) | 4.5 (0.7) | 18.2 (1.2) |

| Poland | 4000 | 3.8 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.1) | 5.1 (0.3) | 1.5 (0.2) | 8.7 (0.5) |

| Spain | 2121 | 15.9 (1.3) | 4.1 (0.7) | 61.5 (2.6) | 3.5 (0.7) | 64.5 (2.6) |

| United States | 5692 | 42.3 (1.0) | 16.2 (0.6) | 11.3 (0.5) | 11.1 (0.6) | 44.2 (1.1) |

| All | 90 027 | 16.9 (0.2) | 3.6 (0.1) | 10.5 (0.2) | 4.0 (0.1) | 24.8 (0.2) |

County income group reflects economic development status at time of data collection based on the World Bank country level ranking.

Indicates the total unweighted number of respondents who responded to illicit drug use question(s).

Prevalence estimates are based on weighted data.

All European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders surveys (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands and Spain) asked 3 separate questions on extramedical use (on whether it was used without a prescription, more than prescribed, and so regularly in a nonmedical setting that you could not stop) for each prescription drug category. In contrast, most other surveys asked a single question pertaining to extramedical use of specific or any prescription drugs. The more detailed question structure in the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders interviews is likely the reason for the high rates of prescription drug use in these surveys.

Respondents were included in the category “any drugs” if they provided information relating to the use of at least 1 drug.

Used at least 1 of the drug categories considered: cannabis, cocaine, prescription drugs, and other drugs. Any drugs not captured by the first 3 categories were grouped as other drugs.

Table 2 shows prevalence estimates of lifetime DUDs overall and conditional on ever having used drugs, as well as remission rates overall and among those with the specific use disorders. The lifetime prevalence of drug abuse and drug dependence in the total sample were 2.2% (SE, 0.1%) and 1.2% (SE, 0.1%), respectively (Table 2). Again, there was considerable geographic variation. Around 1 in 7 drug users developed a DUD (14.0% [SE, 0.3%]), with the rate of abuse (9.1% [SE, 0.2%]) higher than dependence (5.0% [SE, 0.2%]). Remission prevalence rates for the entire cohort were 1.8% (SE, 0.1%) for abuse and 0.9% (SE, <0.1%) for dependence. Conditional remission estimates were 78.0% (SE, 1.1%) for drug abuse and 70.7% (SE, 1.7%) for drug dependence.

Table 2. Conditional Lifetime Prevalence of DSM-IV Drug Use Disorders and Remission in the World Mental Health Surveysa.

| Countryd | No.e | Prevalence, % (SE)b | Conditional Prevalence, % (SE)b,c | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abusef | Dependence | Remission From Abuseg | Remission From Dependence | Abuse Among Usersf | Dependence Among Users | Any Drug Use Disorder Among Users | Remission Among Individuals With Lifetime Abuseg | Remission Among Individuals With Lifetime Dependence | ||

| Low and lower-middle income | 18 179 | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.0) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.2 (0) | 6.1 (0.6) | 3.2 (0.5) | 9.3 (0.9) | 75 (5.5) | 56.4 (6.7) |

| Colombia | 4426 | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | 6.8 (1.3) | 6.4 (1.3) | 13.2 (2.1) | 75 (8.3) | 54.7 (7.6) |

| Iraq | 4332 | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 11.4 (7.6) | 0.9 (0.9) | 12.3 (7.6) | NAh | NA |

| Nigeria | 2143 | 1.0 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.0) | 5.0 (1.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 5.1 (1.1) | NA | NA |

| Peru | 3930 | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 5.8 (0.8) | 2.1 (0.8) | 8.0 (1.2) | NA | NA |

| China | 1628 | 0.4 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.4 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.0) | 7.5 (3.2) | 0.2 (0.2) | 7.7 (3.2) | NA | NA |

| Ukraine | 1720 | 0.4 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.2) | 5.0 (2.5) | 6.7 (1.9) | 11.7 (2.6) | NA | NA |

| Upper-middle income | 20 051 | 1.7 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | 10.4 (0.7) | 4.9 (0.6) | 15.3 (0.9) | 67.7 (3.2) | 64.1 (4.4) |

| Brazil | 5037 | 1.5 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.3) | 1.3 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.2) | 8.6 (1.0) | 7.9 (1.6) | 16.5 (1.8) | 83.1 (5.2) | 62.4 (6.3) |

| Bulgaria | 2233 | 0.2 (0.1) | NA | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.0 (0.0) | 2.3 (1.2) | 0.0 (0.0) | 2.3 (1.2) | NA | NA |

| Lebanon | 1031 | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.1 (0.1 | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.0 (0.0) | 5.6 (4.6) | 2.3 (1.5) | 7.8 (3.8) | NA | NA |

| Medellín | 1673 | 3.4 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.4) | 2.9 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.3) | 14.9 (2.2) | 8.2 (1.7) | 23.1 (2.8) | 84.9 (4.6) | 57.3 (10.1) |

| Mexico | 5767 | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 9.1 (1.5) | 4.9 (1.1) | 14.0 (1.6) | 76.6 (6.6) | NA |

| South Africa | 4310 | 3.4 (0.3) | 0.6 (0.2) | 1.6 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.1) | 12.4 (1.4) | 2.3 (0.6) | 14.7 (1.8) | 48.2 (5.6) | NA |

| High income | 51 797 | 3.0 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.1) | 9.1 (0.3) | 5.2 (0.2) | 14.3 (0.3) | 80.5 (1.2) | 72.9 (1.9) |

| Argentina | 2116 | 3.0 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.3) | 2.1 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.2) | 11.4 (1.7) | 4.4 (1.1) | 15.9 (1.9) | 68.2 (7) | 63.9 (8.5) |

| Australia | 8463 | 4.6 (0.2) | 2.9 (0.3) | 4.0 (0.2) | 2.3 (0.3) | 21.6 (1.2) | 13.5 (1.4) | 35.1 (1.7) | 86.2 (1.8) | 79.8 (3.6) |

| Belgium | 1043 | 3.4 (0.7) | 1.1 (0.6) | 2.3 (0.5) | 0.4 (0.2) | 7.1 (1.4) | 2.3 (1.3) | 9.4 (1.8) | 69.2 (13.1) | NA |

| France | 1436 | 2.6 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.3) | 2.2 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.3) | 5.0 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.5) | 6.6 (0.9) | 84.3 (2.7) | NA |

| Germany | 1323 | 2.4 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.3) | 2.2 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.1) | 3.6 (0.7) | 0.7 (0.4) | 4.4 (0.8) | 90 (6.1) | NA |

| Israel | 4824 | 1.4 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.1) | 10.8 (1.3) | 2.3 (0.6) | 13.1 (1.4) | 81.6 (4.8) | NA |

| Italy | 1779 | 2.1 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.1) | 1.8 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.1) | 3.1 (0.6) | 0.6 (0.2) | 3.7 (0.6) | 87.4 (5.9) | NA |

| Japan | 1671 | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.0 (0.0) | 3.0 (1.4) | 0.7 (0.5) | 3.7 (1.5) | NA | NA |

| Murcia | 1459 | 2.4 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.7 (0.7) | 0.6 (0.2) | 10.0 (2.4) | 5.2 (1.5) | 15.2 (2.5) | NA | NA |

| Netherlands | 1094 | 1.0 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.6) | 0.9 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.6) | 2.9 (0.9) | 3.0 (1.7) | 5.8 (1.8) | NA | NA |

| New Zealand | 12 790 | 3.1 (0.2) | 2.5 (0.2) | 2.6 (0.2) | 1.6 (0.1) | 7.2 (0.5) | 5.8 (0.4) | 13.0 (0.6) | 82.8 (2.3) | 65.2 (3.4) |

| Northern Ireland | 1986 | 2.7 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.2) | 1.5 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.1) | 14.8 (2.3) | 3.5 (0.9) | 18.4 (2.5) | 54.2 (8.6) | NA |

| Poland | 4000 | 1.2 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.0) | 13.5 (1.7) | 2.8 (0.9) | 16.2 (2.0) | 36.8 (7.1) | NA |

| Spain | 2121 | 3.8 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.1) | 3.2 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.1) | 5.9 (0.9) | 0.5 (0.1) | 6.3 (0.9) | 84.8 (5.7) | NA |

| United States | 5692 | 4.9 (0.3) | 3.5 (0.2) | 4.1 (0.2) | 2.9 (0.2) | 11.1 (0.7) | 7.8 (0.5) | 18.9 (0.9) | 83.1 (1.7) | 83.5 (2.6) |

| All | 90 027 | 2.2 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.1) | 1.8 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.0) | 9.1 (0.2) | 5.0 (0.2) | 14.0 (0.3) | 78 (1.1) | 70.7 (1.7) |

Abbreviation: NA, not available.

Disorder and remission diagnoses are for any drug.

Prevalence estimates are based on weighted data.

Inclusion in the denominator is conditional on persons having met a certain level of drug involvement.

Country income group reflects economic development status at time of data collection based on the World Bank country level ranking.

Indicates the total unweighted number of respondents.

Excludes persons with lifetime drug dependence.

Remission from abuse excludes persons with lifetime drug dependence.

Cells marked NA indicate the estimates were not provided because of small sample sizes (n < 30).

Age at Onset and Time to Transition Across Stages of Involvement

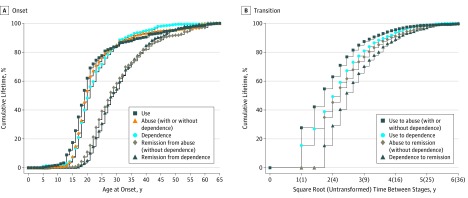

The Figure shows the cumulative age at onset curves for onset of illicit drug use, abuse, dependence, remission from abuse and remission from dependence (Figure, A), and the cumulative time to transition between drug stages (Figure, B). Onset of drug use largely occurred during the late teenage years (median [interquartile range; IQR] age at onset, 19 [16-24] years). For DUDs, the median (IQR) age at onset was slightly earlier for abuse (20 [18-25] years ) than dependence (21 [18-26] years). This was similar for remission, with the median age at onset of remitting from abuse 1 year younger than the median age at onset of dependence remission (28 [IQR, 23-37] years vs 29 [IQR, 24-36] years).

Figure. Age at Onset and Transition Times Between Drug Use, Use Disorders, and Remission.

A, The cumulative age at onset curves for illicit drug use, abuse (without hierarchy), dependence, remission from abuse, and remission from dependence. Each curve includes respondents with and without the specific diagnosis, where age at onset for the latter is censored at age of interview. Estimates were scaled up to reach 100%. B, The cumulative curves for time to transition between various drug stages. Each curve includes only respondents with a diagnosis of the second stage. In A and B, persons with missing age at onset of remission were excluded from associated curves (n = 147 for remission from abuse; n = 104 for remission from dependence).

The transition from initial use to DUD onset was often fast, with 54.7% (95% CI, 54.5-54.8) of all users who developed abuse doing so within 3 years of first use. Median (IQR) time to dependence was slightly longer, at 5 (2-8) years from first use. Among those that eventually remitted, median (IQR) time with the disorder was slightly longer for dependence at 6 (4-11) years, compared with abuse at 5 (3-9) years.

Factors Associated With Transitions Between Stages of Drug Involvement

Table 3 summarizes the results of 5 models investigating the association of each substance variable with transitions between stages of drug involvement, with adjustment for all sociodemographic variables. (Complete set of results are shown in eTables 2-7 in the Supplement.)

Table 3. Association of Each Substance Variable With Transitions Between Stages of Lifetime Illicit Drug Use, Use Disorders, and Remission, Adjusted for All Sociodemographic Variablesa.

| Model | Transition 1: Commencing Use | Transition 2: Use to Abuse, With and Without Dependence | Transition 3: Use to Dependence | Transition 4: Remission From Abuse, Without Dependencee | Transition 5: Remission From Dependencee | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio, (95% CI) | χ21 | P Value | Odds Ratio, (95% CI) | χ21 | P Value | Odds Ratio, (95% CI) | χ21 | P Value | Odds Ratio, (95% CI) | χ21 | P Value | Odds Ratio, (95% CI) | χ21 | P Value | |

| Total sample size, No.b | 90 022 | 23 073 | 23 073 | 2088 | 1167 | ||||||||||

| 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Per 10% of age cohort already using drugsc | 1.31 (1.29-1.33) | 1389.01 | <.001 | 1.11 (1.07-1.16) | 24.84 | <.001 | 1.10 (1.03-1.18) | 7.16 | .007 | 1.65 (1.54-1.77) | 197.06 | <.001 | 1.65 (1.44-1.88) | 53.87 | <.001 |

| 2 | |||||||||||||||

| Per 10% of age cohort already using alcoholc | 1.51 (1.49-1.54) | 2043.51 | <.001 | 1.13 (1.07-1.19) | 21.85 | <.001 | 1.08 (0.99-1.18) | 2.94 | .09 | 1.44 (1.30-1.61) | 44.00 | <.001 | 1.67 (1.12-2.50) | 6.22 | .01 |

| 3 | |||||||||||||||

| Highest level of individual’s alcohol involvementd | |||||||||||||||

| Use | 4.64 (4.39-4.90) | 3087.76 | <.001 | 1.50 (1.26-1.80) | 19.60 | <.001 | 1.39 (0.99-1.96) | 3.53 | .06 | 1.39 (1.11-1.72) | 8.61 | .003 | 1.94 (1.19-3.18) | 6.95 | .008 |

| Abuse | 10.78 (9.38-12.40) | 1120.27 | <.001 | 5.52 (4.40-6.92) | 219.64 | <.001 | 3.80 (2.50-5.78) | 39.03 | <.001 | 1.36 (1.07-1.72) | 6.38 | .01 | 2.18 (1.32-3.62) | 9.14 | .003 |

| Dependence | 12.81 (10.29-15.94) | 522.38 | <.001 | 6.48 (4.94-8.50) | 182.37 | <.001 | 6.33 (4.12-9.73) | 71.06 | <.001 | 1.49 (1.12-1.99) | 7.59 | .006 | 1.76 (1.09-2.84) | 5.30 | .02 |

| Remission | 4.08 (3.20-5.21) | 128.18 | <.001 | 2.59 (1.78-3.78) | 24.48 | <.001 | 2.01 (1.20-3.37) | 7.08 | .008 | 2.25 (1.67-3.02) | 28.88 | <.001 | 3.28 (1.99-5.40) | 21.70 | .001 |

| Joint test of all 4 indicators, χ24 (P value) | NA | 3251.41 | <.001 | NA | 465.08 | <.001 | NA | 150.16 | <.001 | NA | 30.29 | <.001 | NA | 42.15 | <.001 |

| 4 | |||||||||||||||

| Type of drug(s) already used by individual | |||||||||||||||

| Cannabis | NA | NA | NA | 3.10 (2.53-3.81) | 116.54 | <.001 | 2.53 (1.76-3.63) | 25.02 | <.001 | 1.68 (1.36-2.08) | 22.50 | <.001 | 1.65 (1.20-2.27) | 9.56 | .002 |

| Cocaine | NA | NA | NA | 3.22 (2.79-3.72) | 255.96 | <.001 | 3.54 (2.83-4.42) | 123.08 | <.001 | 1.10 (0.96-1.26) | 1.98 | .16 | 0.88 (0.73-1.06) | 1.74 | .19 |

| Other | NA | NA | NA | 2.62 (2.28-3.01) | 184.01 | <.001 | 3.25 (2.61-4.04) | 112.36 | <.001 | 0.80 (0.71-0.89) | 16.55 | <.001 | 0.92 (0.75-1.12) | 0.67 | .41 |

| Joint test of all 3 indicators, χ23 (P value) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 696.02 | <.001 | NA | 379.52 | <.001 | NA | 43.05 | <.001 | NA | 12.99 | .005 |

| 5 | |||||||||||||||

| Individual used ≥2 drug types | NA | NA | NA | 5.17 (4.66-5.73) | 976.45 | <.001 | 5.99 (5.02-7.16) | 390.67 | <.001 | 0.86 (0.76-0.98) | 5.45 | .02 | 0.91 (0.74-1.13) | 0.74 | .39 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

All transitions are based on weighted person-year data. Each model was estimated for all transitions with only the 1 substance variable entered at a time as factors of each transition controlling for person-year age groups; sex; education level; major depressive episode; broad bipolar disorder; number of anxiety disorders; and survey (transition 1); all controls specified for transition 1 as well as age tertile of commencing alcohol use (transition 2); all controls specified for transition 2 as well as drug abuse (transition 3); and all controls specified for transition 2 as well as speed to transition from use to disorder and years with disorder (transitions 4 and 5).

Indicates the total unweighted number of respondents included in model conditioning on initial stage.

Percentage (divided by 10) of ±5-year specific cohort who had used the substance by the prior person-year.

Alcohol transition variables are mutually exclusive; only the highest alcohol level ever having been met (use < abuse < dependence < remission) is indicated for each person year.

Individuals with a missing age at onset of remission were excluded from the model (n = 147 for remission from abuse and n = 104 for remission from dependence).

Cohort-Level Substance Use

In the transition models that considered prevalence of drug use in an individual’s age cohort (model 1), an increase in the drug use of the cohort that an individual was in was associated with an increased individual risk of commencing drug use (OR, 1.31 [95% CI, 1.29-1.33]; P < .001), transitioning from use to abuse (OR, 1.11 [95% CI, 1.07-1.16]; P < .001), transitioning from use to dependence (OR, 1.10 [95% CI, 1.03-1.18]; P = .007), remitting from abuse (OR, 1.65 [95% CI, 1.54-1.77]; P < .001), and remitting from dependence (OR, 1.65 [1.44-1.88]; P < .001). With the exception of transitions to dependence, similar results were also observed when examining the prevalence of cohort alcohol use (model 2; ORs: commencing use, 1.51 [95% CI, 1.49-1.54]; P < .001; transitioning from use to abuse, 1.13 [95% CI, 1.07-1.19]; P < .001; remission from abuse, 1.44 [95% CI, 1.30-1.61]; P < .001; remission from dependence, 1.67 [95% CI, 1.12-2.50]; P = .01).

Individual-Level Substance Use History

At the individual level, having already developed alcohol abuse was strongly associated with an increased risk of starting drug use (OR, 10.78 [95% CI, 9.38-12.40]; P < .001), transitioning to drug abuse (OR, 5.52 [95% CI, 4.40-6.92]; P < .001) or dependence (OR, 3.80 [95% CI, 2.50-5.78]; P < .001), but also remitting from drug abuse (OR, 1.36 [95% CI, 1.07-1.72]; P = .01) or dependence (OR, 2.18 [95% CI, 1.32-3.62]; P = .003; model 3). Similar results were found for having previously developed alcohol dependence (ORs: use, 12.81 [95% CI, 10.29-15.94]; P < .001; abuse, 6.48 [95% CI, 4.94-8.50]; P < .001; dependence, 6.33 [95% CI, 4.12-9.73]; P < .001; remission from abuse, 1.49 [95% CI, 1.12-1.99]; P = .006; and remission from dependence, 1.76 [95% CI, 1.09-2.84]; P = .02) and remission from either alcohol abuse or dependence (ORs: use, 4.08 [95% CI, 3.20-5.21]; P < .001; abuse, 2.59 [95% CI, 1.78-3.78]; P < .001; dependence, 2.01 [95% CI, 1.20-3.37]; P < .001; remission from abuse, 2.25 [95% CI, 1.67-3.02]; P < .001; and remission from dependence, 3.28 [95% CI, 1.99-5.40]; P < .001).

Considering the types of drugs used (model 4), cocaine increased risk of transitioning to drug dependence (OR, 3.54 [95% CI, 2.83-4.42]; P < .001), as did other drugs (OR, 3.25 [95% CI, 2.61-4.04]; P < .001); people with a history of cannabis use were also more likely to remit from both drug abuse (OR, 1.68 [95% CI, 1.36-2.08]; P < .001) and drug dependence (OR, 1.65 [95% CI, 1.20-2.27]; P = .002) than those who had not used cannabis.

When considering only the number of drugs used (model 5), the use of 2 or more drug types increased the odds of transitioning to abuse (OR, 5.17 [95% CI, 4.66-5.73]; P < .001) and dependence (OR, 5.99 [95% CI, 5.02-7.16]; P < .001) and reduced the odds of remitting from abuse (OR, 0.86 [95% CI, 0.76-0.98]; P = .02).

Both Individual and Cohort Substance Use History

Table 4 presents the results obtained when including all individual and cohort-level substance use variables considered in the same model (also adjusting for sociodemographic variables). Once adjusting for an individual’s own prior substance involvement, an increase in their cohort’s drug use was associated with an increased individual risk of commencing drug use (OR, 1.12 [95% CI, 1.11-1.14]; P < .001) and remitting from abuse (OR, 1.57 [95% CI, 1.46-1.69]; P < .001) and dependence (OR, 1.59 [95% CI, 1.39-1.83]; P < .001) but was no longer associated with developing DUDs. Similar results were observed for cohort alcohol use; an increase in prevalence of cohort alcohol use was associated with increased individual risk only of commencing drug use (OR, 1.28 [95% CI, 1.26-1.31]; P < .001) and remitting from abuse (OR, 1.11 [95% CI, 1.00-1.22]; P = .04). but was no longer associated with developing DUDs. Most other effects observed in the separate models remained significant. Analyses at the country income level were also investigated, the results of which are shown in eTables 8-13 in the Supplement. Findings were largely consistent between country income group analyses and the pooled analyses presented in this study.

Table 4. Associations of All Substance Variables With Transitions Between Stages of Lifetime Illicit Drug Use, Use Disorders, and Remission, Adjusted for All Sociodemographic Variablesa.

| Model 6 | Transition 1: Commencing Use | Transition 2: Use to Abuse, With and Without dependence | Transition 3: Use to Dependence | Transition 4: Remission From Abuse, Without Dependenceb | Transition 5: Remission From Dependenceb | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | χ21 | P Value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | χ21 | P Value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | χ21 | P Value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | χ21 | P Value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | χ21 | P Value | |

| Total sample size, No.c | 90 022 | 23 073 | 23 073 | 2088 | 1167 | ||||||||||

| Per 10% of age cohort already using drugsd | 1.12 (1.11-1.14) | 205.46 | <.001 | 1.04 (0.99-1.09) | 2.19 | .14 | 1.04 (0.96-1.13) | 1.04 | .31 | 1.57 (1.46-1.69) | 138.99 | <.001 | 1.59 (1.39-1.83) | 44.36 | <.001 |

| Per 10% of age cohort already using alcohold | 1.28 (1.26-1.31) | 639.15 | <.001 | 0.99 (0.94-1.05) | 0.07 | .79 | 0.94 (0.85-1.04) | 1.28 | .26 | 1.11 (1.00-1.22) | 4.22 | .04 | 1.19 (0.86-1.64) | 1.07 | .300 |

| Highest level of individual’s alcohol involvemente | |||||||||||||||

| Use | 3.59 (3.40-3.80) | 2027.16 | <.001 | 1.22 (1.02-1.47) | 4.54 | .03 | 1.17 (0.81-1.70) | 0.74 | .39 | 1.00 (0.79-1.27) | 0.00 | >.99 | 1.68 (1.03-2.74) | 4.33 | .04 |

| Abuse | 8.20 (7.16-9.38) | 933.29 | <.001 | 3.76 (2.98-4.74) | 125.44 | <.001 | 2.56 (1.65-3.97) | 17.43 | <.001 | 0.92 (0.71-1.20) | 0.37 | .55 | 1.90 (1.15-3.15) | 6.21 | .01 |

| Dependence | 9.77 (7.90-12.08) | 441.06 | <.001 | 4.33 (3.27-5.74) | 104.69 | <.001 | 4.19 (2.67-6.59) | 38.54 | <.001 | 1.11 (0.82-1.49) | 0.43 | .51 | 1.5 (0.93-2.42) | 2.78 | .10 |

| Remission | 3.10 (2.43-3.95) | 84.01 | <.001 | 1.76 (1.21-2.57) | 8.58 | .003 | 1.39 (0.81-2.40) | 1.41 | .24 | 1.59 (1.18-2.14) | 9.14 | .003 | 2.78 (1.69-4.55) | 16.43 | <.001 |

| Joint test of all 4 indicators, χ24 (P value) | NA | 2238.03 | <.001 | NA | 304.38 | <.001 | NA | 99.35 | <.001 | NA | 26.23 | <.001 | NA | 35.78 | <.001 |

| Type of drug used by individual | |||||||||||||||

| Cannabis | NA | NA | NA | 0.84 (0.62-1.13) | 1.36 | .24 | 1.07 (0.66-1.73) | .07 | .79 | 2.06 (1.61-2.64) | 32.54 | <.001 | 1.65 (1.16-2.34) | 7.62 | .006 |

| Cocaine | NA | NA | NA | 1.42 (1.14-1.76) | 9.75 | .002 | 2.35 (1.78-3.10) | 36.01 | <.001 | 1.28 (1.08-1.52) | 7.91 | .005 | 0.83 (0.67-1.03) | 2.99 | .08 |

| Other | NA | NA | NA | 0.82 (0.64-1.04) | 2.67 | .10 | 1.48 (1.06-2.07) | 5.31 | .02 | 1.06 (0.88-1.28) | 0.43 | .51 | 0.99 (0.77-1.29) | <.01 | .97 |

| Joint test of all 3 indicators, χ23 (P value) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 35.36 | <.001 | NA | 48.37 | <.001 | NA | 43.82 | <.001 | NA | 11.82 | .008 |

| Individual used ≥2 drug types | NA | NA | NA | 4.69 (3.56-6.18) | 120.52 | <.001 | 2.90 (1.97-4.29) | 28.74 | <.001 | 0.58 (0.46-0.74) | 19.96 | <.001 | 0.83 (0.58-1.18) | 1.07 | .30 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

All transitions are based on weighted person-year data. Each model was estimated for all transitions with all substance variables entered as factors of each transition, controlling for person-year age groups; sex; education level; major depressive episode; broad bipolar disorder; number of anxiety disorders; and survey (transition 1); all controls specified for transition 1 as well as age tertile of commencing alcohol use (transition 2); all controls specified for transition 2 as well as drug abuse (transition 3); and all controls specified for transition 2, as well as speed to transition from use to disorder and years with disorder (transitions 4 and 5).

Individuals with a missing age at onset of remission were excluded from the model (n = 147 for remission from abuse and n = 104 for remission from dependence).

Indicates the total unweighted number of respondents included in model conditioning on initial stage.

Percentage (divided by 10) of ±5-year specific cohort who had used the substance by the prior person year.

Alcohol transition variables are mutually exclusive; only the highest alcohol level ever having been met (use < abuse < dependence < remission) is indicated for each person year.

Discussion

The primary aim of the present study was to provide cross-national data on the epidemiology of drug use, abuse, and dependence and use a unique cross-national data set to examine transitions across levels of involvement with drug use, and the extent to which alcohol and other drug use in an individual’s birth cohort was associated with an individual’s risk of these transitions, in addition to that person’s own prior involvement in alcohol and drug use. At an individual level, extent of involvement with both alcohol and drug use was strongly associated with risks of transitioning into drug abuse and dependence, consistent with previous findings.31,32 Even after having remitted from alcohol use disorder, individuals remained at increased risk of beginning drug use and transitioning to DUDs. Interestingly, individuals who had previously remitted from alcohol use disorder also had a higher likelihood of remitting from DUDs than those who never used alcohol.

After controlling for individual-level substance use history, extent of illicit drug use in an individual’s birth cohort was associated with significantly increased risk of the individual beginning drug use and remitting from DUDs. Cohort alcohol use was also positively associated with commencement of illicit drug use and remission from drug abuse. That is, the more people in an individual’s cohort who had a history of using those substances, the greater the likelihood of the individual remitting from the DUD after developing this disorder.

These findings speak to the social context in which substance use occurs. One of the most consistent findings in substance use research is that substance use of one’s peers is associated with a greater likelihood of involvement with substance use for an individual.33 Here, we have further shown that this is a generalized pattern, whereby not only substance use among one’s friends matters, but also that of one’s peer cohort more generally. This may be through multiple mechanisms, such as associations with perceived drug use norms34 and increased opportunities to use substances.35 Furthermore, cohort substance use was shown not only to be associated with greater involvement with drugs, but rather to have even stronger associations observed for transitions to remission from DUDs. This may reflect that individuals exposed to higher cohort-level prevalence also have greater access to treatment services than individuals exposed to lower cohort-level prevalence, or perhaps that as cohort substance use increases those who are transitioning to these disorders may be less prone to problematic use or use disorders at the individual level and, as a result, enter remission from those disorders at a higher rate. These findings also suggest that the risk for commencing drug use and remission from problems is not constant but varies, in this case according to the extent to which substance use is occurring among one’s peers.

Although higher rates of use in an individual’s cohort was associated with an increased likelihood the individual will start using drugs, there was no independent association of cohort use with the transition to abuse or dependence once use had begun. This suggests that while higher rates of use in an individual’s cohort increase the likelihood that the individual will start using drugs, the propensity to transition to problematic use is not affected by such external variables; by contrast, we found that it was affected by their own prior substance use history. Therefore, any intervention aiming to reduce substance use within a cohort might also reduce individual-level risk for transitioning into greater levels of involvement with drug use. The type of substance such interventions should target warrants further investigation, especially considering that cohort alcohol use had a stronger association with commencing drug use than cohort drug use did. However, implementation would ideally be early in life and before opportunities to use either substance arise (eTable 16 in the Supplement). If this occurred, the smaller group of individuals who nonetheless developed DUDs despite the decrease in prevalence of use within that cohort would be more refractive cases.

Limitations

This study provided detail regarding the prevalence and timing of various stages across the full trajectory of both alcohol and illicit drug use, with clinically valid diagnoses and inclusion of contextual factors not previously accounted for within the literature. Data on age at onset for each stage were obtained via retrospective self-report and may be subject to forward telescoping, whereby participants are more likely to report events as occurring closer to the point of the interview than is accurate.36,37 However, this literature does not suggest that the order of recalled events will be altered.

Investigating the interactive effects of the personal and contextual variables on risk of transitioning involvement with illicit drugs was beyond the scope of this article. However, future work should investigate whether conditional associations exist between individual-level factors (eg, substance use, history of mental disorder) and cohort contextual variables that affect individuals’ risk of commencing use and transitioning to greater involvement with drugs.

The WMH surveys have several important limitations. There is not full representation of all countries, regions, country income levels or other country characteristics. There was variation in response rates across countries, the year in which the studies were administered, and possibly cross-national differences in willingness to disclose personal information about drug use and problems. Respondent information is subject to the limitations of recall inherent in retrospective reporting, leading to potential underestimates in lifetime prevalence. Survival bias may also contribute to downward bias in lifetime estimates.

In addition to these general limitations, there are some limitations specific to the assessment of DUDs. The WMH surveys are household surveys, which have limitations when used to assess less common and more stigmatized behaviors. Illicit drug use can be a rare or geographically concentrated occurrence, and surveys such as the WMH surveys that rely on stratified sampling methods are poorly suited to capturing concentrated geographic pockets of drug use. Furthermore, the use of households as the primary sampling unit will not capture marginalized groups who do not live in traditional household contexts (eg, individuals who are homeless, in prison, in the hospital, or in other nonhousehold accommodations). These factors mean that prevalence rates presented here should be considered lower-bound estimates; true lifetime prevalence of DUDs may be substantially higher.

Transition times to drug use disorders (DUDs) have been shown to differ widely depending on substance class.38 Because most surveys assessed DUDs at the general illicit drug level, it was not possible to evaluate transition times at the drug-specific level. The estimates presented here therefore represent mean values of first transitions across all individuals who use (single and multitype) illicit drugs.

Owing to the way in which symptom onset and recency is assessed in the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, it was only possible to assess remission at the time of interview. Given the long-term nature of DUDs, additional information on lifetime remission (ie, any period in life with an absence of symptoms for more than 12 months) may have made it possible to find other variables were associated with remission.

Conclusions

We have found that, across countries, an individual’s personal risk of transitioning to greater involvement with drug use was associated with their history of involvement with drugs and alcohol and the substance use histories of their age cohort. These variables were associated with transitioning into and out of problematic drug use, particularly when they are considered together, in addition to a range of other sociodemographic correlates. These findings have important implications for understanding of pathways into and out of problematic substance use.

eTable 1. WMH sample characteristics by World Bank income categories

eMethods. Criteria for being asked questions about drug use disorders

eTable 2. Multivariate associations of cohort drug use and socio-demographic variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission (Model 1)

eTable 3. Multivariate associations of cohort alcohol use and socio-demographic variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission (Model 2)

eTable 4. Multivariate associations of highest level of alcohol involvement and socio-demographic variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use disorders and remission (Model 3)

eTable 5. Multivariate associations of the type of drug(s) used and socio-demographic variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use disorders and remission (Model 4)

eTable 6. Multivariate associations of poly-drug type usage and socio-demographic variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use disorders and remission (Model 5)

eTable 7. Multivariate associations of all cohort and individual substance-related variables and socio-demographic variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission (Model 6)

eTable 8. Multivariate association of each substance-related variable (excluding all others) with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission for low & lower-middle income countries, adjusted for all sociodemographic variables

eTable 9. Multivariate associations of all substance-related variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission for low & lower-middle income countries, adjusted for all sociodemographic variables

eTable 10. Multivariate association of each substance-related variable (excluding all others) with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission for upper-middle income countries, adjusted for all sociodemographic variables

eTable 11. Multivariate associations of all substance-related variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission for upper-middle income countries, adjusted for all sociodemographic variables

eTable 12. Multivariate association of each substance-related variable (excluding all others) with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission for high income countries, adjusted for all sociodemographic variables

eTable 13. Multivariate associations of all substance-related variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission for high income countries, adjusted for all sociodemographic variables

eTable 14. Multivariate association of each substance-related variable (excluding all others) with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission among the subset of surveys that assessed dependence without abuse

eTable 15. Multivariate associations of all substance-related variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission among the subset of surveys that assessed dependence without abuse

eTable 16. Association of each substance-related variable (Model 1 and 2) and all substance use variables (Model 6) with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission, adjusted for all sociodemographic variables

eReferences.

References

- 1.Lopez-Quintero C, Pérez de los Cobos J, Hasin DS, et al. . Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;115(1-2):120-130. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butterworth P, Slade T, Degenhardt L. Factors associated with the timing and onset of cannabis use and cannabis use disorder: results from the 2007 Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2014;33(5):555-564. doi: 10.1111/dar.12183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behrendt S, Wittchen H-U, Höfler M, Lieb R, Beesdo K. Transitions from first substance use to substance use disorders in adolescence: is early onset associated with a rapid escalation? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99(1-3):68-78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffey C, Carlin JB, Lynskey M, Li N, Patton GC. Adolescent precursors of cannabis dependence: findings from the Victorian Adolescent Health Cohort Study. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182(4):330-336. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.4.330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larance B, Gisev N, Cama E, et al. . Predictors of transitions across stages of heroin use and dependence prior to treatment-seeking among people in treatment for opioid dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;191:145-151. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.03.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suliman S, Seedat S, Williams DR, Stein DJ. Predictors of transitions across stages of alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders in South Africa. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71(5):695-703. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalaydjian A, Swendsen J, Chiu WT, et al. . Sociodemographic predictors of transitions across stages of alcohol use, disorders, and remission in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50(4):299-306. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silveira CM, Viana MC, Siu ER, de Andrade AG, Anthony JC, Andrade LH. Sociodemographic correlates of transitions from alcohol use to disorders and remission in the São Paulo megacity mental health survey, Brazil. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46(3):324-332. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdin E, Subramaniam M, Vaingankar JA, Chong SA. The role of sociodemographic factors in the risk of transition from alcohol use to disorders and remission in singapore. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49(1):103-108. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee S, Guo WJ, Tsang A, et al. . Associations of cohort and socio-demographic correlates with transitions from alcohol use to disorders and remission in metropolitan China. Addiction. 2009;104(8):1313-1323. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02595.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall WD, Patton G, Stockings E, et al. . Why young people’s substance use matters for global health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(3):265-279. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00013-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss RD, Mirin SM, Griffin ML, Michael JL. Psychopathology in cocaine abusers: changing trends. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1988;176(12):719-725. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198812000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breslau N, Novak SP, Kessler RC. Psychiatric disorders and stages of smoking. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(1):69-76. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00317-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Period, age, and cohort effects on substance use among young Americans: a decade of change, 1976-86. Am J Public Health. 1988;78(10):1315-1321. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.78.10.1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anthony JC, Warner L, Kessler R. Comparative epidemiology of dependence on tobacco, alcohol, controlled substances, and inhalants: basic findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1994;2(3):244-268. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.2.3.244 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant BF. Prevalence and correlates of drug use and DSM-IV drug dependence in the United States: results of the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse. 1996;8(2):195-210. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(96)90249-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rice JP, Neuman RJ, Saccone NL, et al. . Age and birth cohort effects on rates of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(1):93-99. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2003.tb02727.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant BF. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol use and DSM-IV alcohol dependence in the United States: results of the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58(5):464-473. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasin D, Grant B. The co-occurrence of DSM-IV alcohol abuse in DSM-IV alcohol dependence: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions on heterogeneity that differ by population subgroup. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(9):891-896. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. . Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):8-19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson RA, Gerstein DR. Age, period, and cohort effects in marijuana and alcohol incidence: United States females and males, 1961-1990. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;35(6-8):925-948. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Bond J, Ye Y, Rehm J. Age-period-cohort modelling of alcohol volume and heavy drinking days in the US National Alcohol Surveys: divergence in younger and older adult trends. Addiction. 2009;104(1):27-37. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02391.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keyes KM, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, et al. . The social norms of birth cohorts and adolescent marijuana use in the United States, 1976-2007. Addiction. 2011;106(10):1790-1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03485.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grucza RA, Bucholz KK, Rice JP, Bierut LJ. Secular trends in the lifetime prevalence of alcohol dependence in the United States: a re-evaluation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(5):763-770. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00635.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Degenhardt L, Glantz M, Bharat C, et al. . The impact of cohort substance use upon likelihood of transitioning through stages of alcohol and cannabis use and use disorder: findings from the Australian National Survey on Mental Health and Wellbeing. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018;37(4):546-556. doi: 10.1111/dar.12679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessler RC, Ustün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):93-121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, et al. . Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2006;15(4):167-180. doi: 10.1002/mpr.196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessler RC, Ustun T, eds. The WHO Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lago L, Glantz MD, Kessler RC, et al. . Substance dependence among those without symptoms of substance abuse in the World Mental Health Survey. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26(3). doi: 10.1002/mpr.1557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Degenhardt L, Torres Y, Hinkov H. Have Mt, Glantz MD. Drug-Use Disorders In: Stein DJ, Scott KM, de Jonge P, Kessler RC, eds. Mental Disorders Around the World: Facts and Figures From the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2018:243-262. doi: 10.1017/9781316336168.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Compton WM, Dawson DA, Conway KP, Brodsky M, Grant BF. Transitions in illicit drug use status over 3 years: a prospective analysis of a general population sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(6):660-670. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12060737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flórez-Salamanca L, Secades-Villa R, Hasin DS, et al. . Probability and predictors of transition from abuse to dependence on alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2013;39(3):168-179. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2013.772618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Degenhardt L, Stockings E, Patton G, Hall WD, Lynskey M. The increasing global health priority of substance use in young people. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(3):251-264. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00508-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pollard JW, Freeman JE, Ziegler DA, Hersman MN, Goss CW. Predictions of normative drug use by college students. J Coll Stud Psychother. 2000;14(3):5-12. doi: 10.1300/J035v14n03_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wells JE, Haro JM, Karam E, et al. . Cross-national comparisons of sex differences in opportunities to use alcohol or drugs, and the transitions to use. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46(9):1169-1178. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.553659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shillington AM, Woodruff SI, Clapp JD, Reed MB, Lemus H. Self-reported age of onset and telescoping for cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana across eight years of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2012;21(4):333-348. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2012.710026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson EO, Schultz L. Forward telescoping bias in reported age of onset: an example from cigarette smoking. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2005;14(3):119-129. doi: 10.1002/mpr.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ridenour TA, Lanza ST, Donny EC, Clark DB. Different lengths of times for progressions in adolescent substance involvement. Addict Behav. 2006;31(6):962-983. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. WMH sample characteristics by World Bank income categories

eMethods. Criteria for being asked questions about drug use disorders

eTable 2. Multivariate associations of cohort drug use and socio-demographic variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission (Model 1)

eTable 3. Multivariate associations of cohort alcohol use and socio-demographic variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission (Model 2)

eTable 4. Multivariate associations of highest level of alcohol involvement and socio-demographic variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use disorders and remission (Model 3)

eTable 5. Multivariate associations of the type of drug(s) used and socio-demographic variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use disorders and remission (Model 4)

eTable 6. Multivariate associations of poly-drug type usage and socio-demographic variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use disorders and remission (Model 5)

eTable 7. Multivariate associations of all cohort and individual substance-related variables and socio-demographic variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission (Model 6)

eTable 8. Multivariate association of each substance-related variable (excluding all others) with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission for low & lower-middle income countries, adjusted for all sociodemographic variables

eTable 9. Multivariate associations of all substance-related variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission for low & lower-middle income countries, adjusted for all sociodemographic variables

eTable 10. Multivariate association of each substance-related variable (excluding all others) with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission for upper-middle income countries, adjusted for all sociodemographic variables

eTable 11. Multivariate associations of all substance-related variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission for upper-middle income countries, adjusted for all sociodemographic variables

eTable 12. Multivariate association of each substance-related variable (excluding all others) with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission for high income countries, adjusted for all sociodemographic variables

eTable 13. Multivariate associations of all substance-related variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission for high income countries, adjusted for all sociodemographic variables

eTable 14. Multivariate association of each substance-related variable (excluding all others) with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission among the subset of surveys that assessed dependence without abuse

eTable 15. Multivariate associations of all substance-related variables with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission among the subset of surveys that assessed dependence without abuse

eTable 16. Association of each substance-related variable (Model 1 and 2) and all substance use variables (Model 6) with transitions between stages of lifetime illicit drug use, use disorders and remission, adjusted for all sociodemographic variables

eReferences.