Abstract

PURPOSE

Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) is increasingly used for routine clinical management of prostate cancer. To inform targeted treatment strategies, 3,476 clinically advanced prostate tumors were analyzed by CGP for genomic alterations (GAs) and signatures of genomic instability.

METHODS

Prostate cancer samples (1,660 primary site and 1,816 metastatic site tumors from unmatched patients) were prospectively analyzed by CGP (FoundationOne Assay; Foundation Medicine, Cambridge, MA) for GAs and genomic signatures (genome-wide loss of heterozygosity [gLOH], microsatellite instability [MSI] status, tumor mutational burden [TMB]).

RESULTS

Frequently altered genes were TP53 (44%), PTEN (32%), TMPRSS2-ERG (31%), and AR (23%). Potentially targetable GAs were frequently identified in DNA repair, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and RAS/RAF/MEK pathways. DNA repair pathway GAs included homologous recombination repair (23%), Fanconi anemia (5%), CDK12 (6%), and mismatch repair (4%) GAs. BRCA1/2, ATR, and FANCA GAs were associated with high gLOH, whereas CDK12-altered tumors were infrequently gLOH high. Median TMB was low (2.6 mutations/Mb). A subset of cases (3%) had high TMB, of which 71% also had high MSI. Metastatic site tumors were enriched for the 11q13 amplicon (CCND1/FGF19/FGF4/FGF3) and GAs in AR, LYN, MYC, NCOR1, PIK3CB, and RB1 compared with primary tumors.

CONCLUSION

Routine clinical CGP in the real-world setting identified GAs that are investigational biomarkers for targeted therapies in 57% of cases. gLOH and MSI/TMB signatures could further inform selection of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors and immunotherapies, respectively. Correlation of DNA repair GAs with gLOH identified genes associated with homologous recombination repair deficiency. GAs enriched in metastatic site tumors suggest therapeutic strategies for metastatic prostate cancer. Lack of clinical outcome correlation was a limitation of this study.

INTRODUCTION

Genomic alterations (GAs) that drive prostate cancer have been elucidated by profiling primary tumors.1,2 Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) is increasingly used for routine clinical management of patients with prostate cancer,3 with accumulating evidence associating GAs with responses to therapy. In clinical trials, candidate genomic biomarkers include BRCA1/BRCA2/ATM for poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors,4 PTEN/AKT for AKT inhibitors,5,6 and PIK3CB for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-β inhibitors.7 Responses to immunotherapy have been associated with CDK12 GAs,8 POLE GAs,9 and tumor mutational burden-high (TMB-H)9 or microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) genomic signatures.10

CONTEXT

Key Objective

In this study, we use real-world data from routine prospective clinical genomic profiling to evaluate genomic alterations (GAs) and genomic signatures in primary and metastatic prostate cancer.

Knowledge Generated

We evaluated the landscape of GAs in prostate cancer and identified those that are enriched in metastatic site tumors. Approximately 3% of cases had high microsatellite instability and/or high tumor mutational burden status. Specific DNA damage response alterations were associated with genome-wide loss of heterozygosity.

Relevance

Fifty-seven percent of cases harbored a GA associated with targeted therapy approaches. GAs enriched in metastatic site tumors suggest therapeutic strategies for metastatic prostate cancer. Genomic signatures, including microsatellite instability, tumor mutational burden, and genome-wide loss of heterozygosity, may further refine biomarker development for poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors and immunotherapies.

GAs that are associated with castration resistance and metastatic progression have been identified by comparing primary versus metastatic tumors,2,11-13 including an analysis of 1,013 prostate tumors from seven independent whole-exome sequencing studies2 and longitudinal genomic profiling.14,15 To date, the largest study of primary versus metastatic tumors using a single targeted sequencing assay included 200 primary and 304 metastatic tumors.3 To refine further the genomics of prostate cancer in the real-world setting and to inform rational therapy selection and drug development, we assessed GAs and genomic signatures from routine prospective CGP on 1,660 primary and 1,816 metastatic site tumors from unmatched patients.

METHODS

Consecutive CGP results were reported for 3,476 unique patients with prostate cancer by prospective sequencing (median coverage, 743×) of tissue samples using a validated assay16 (FoundationOne; Foundation Medicine, Cambridge, MA; Appendix Table A1). For patients with multiple samples, the sample with the highest sequencing quality metrics was included. Age and site of specimen collection were abstracted from accompanying pathology reports, clinical notes, and requisition forms. The pathologic diagnosis of each case was confirmed on routine hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides. Results were analyzed for GAs and gene signatures (TMB, MSI, genome-wide loss of heterozygosity [gLOH]). Germline/somatic mutation calls were predicted without a matched normal; in validation testing of 480 tumor-only sequencing calls against matched normal samples, accuracy was 95% for somatic and 99% for germline calls.17 Enrichment was defined as the difference in GA frequency between metastatic and primary sites. Potentially targetable GAs were defined by European Society for Medical Oncology Scale for Clinical Actionability of Molecular Targets criteria.18 The Appendix provides additional details on the methods used in this study.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

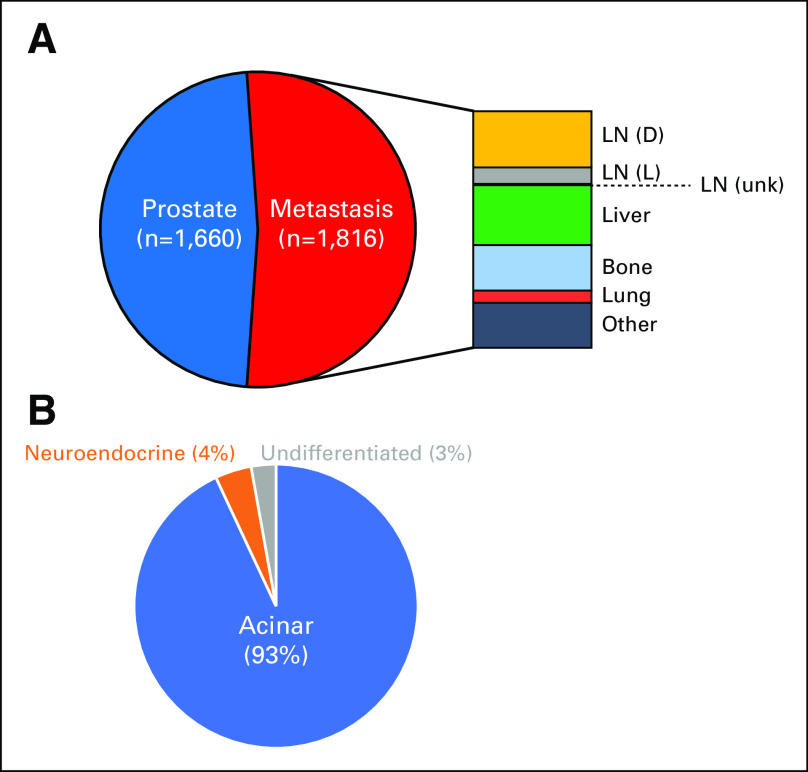

CGP was performed in the course of routine clinical care on tissue samples from 3,476 unique patients with prostate cancer (median age, 66 years; range, 34 to 94 years), including 1,660 samples from the prostate primary site and 1,816 samples from metastatic sites of unmatched patients (Appendix Fig A1).

GAs in Primary and Metastatic Site Tumors

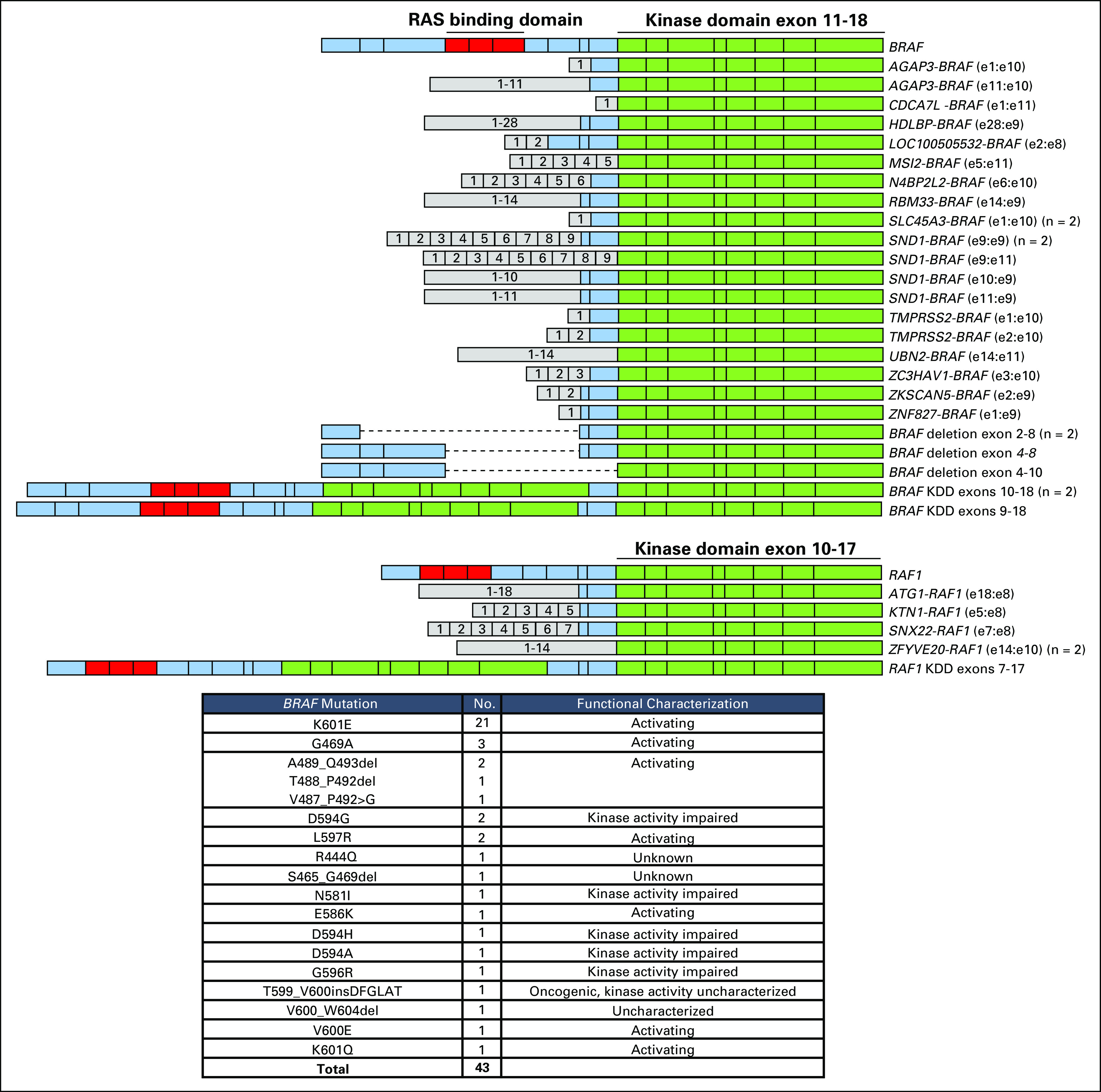

Overall, there was an average of 4.5 GAs per tumor (primary, 3.5 GAs; metastatic, 5.5 GAs). Frequently altered genes were TP53 (43.5%), PTEN (32.2%), TMPRSS2-ERG (31.2%), AR (22.5%), MYC (12.3%), BRCA2 (9.8%), RB1 (9.7%), APC (9.3%), MLL3/KMT2C (7.8%), SPOP (7.7%), PIK3CA (6.0%), and CDK12 (5.6%; Fig 1A). ETS fusions were observed in 35.5% of cases. Activating BRAF or RAF1 fusions/rearrangements were observed in 1.2% of cases (35 BRAF and seven RAF1; Appendix Fig A2).

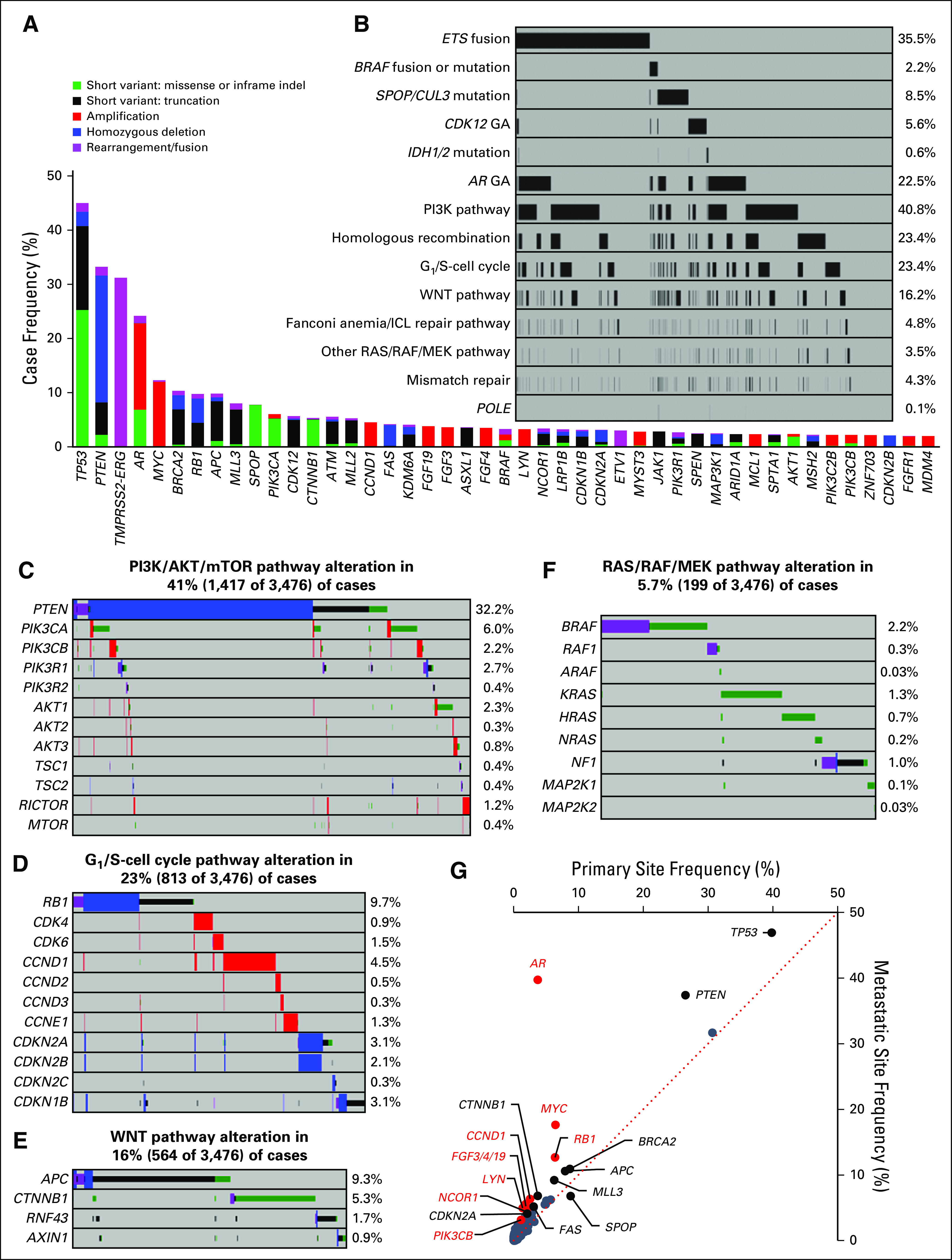

FIG 1.

Genomic characterization of primary and metastatic site prostate tumors. (A) The frequency of genomic alterations (GAs) identified in tumors from 3,476 patients with prostate cancer. Genes altered in 2% or more of cases are shown. (B) Frequency of major pathway alterations, including ETS fusions, BRAF rearrangements/mutations, SPOP/CUL3 mutations, CDK12 GAs, IDH1/2 mutations, AR GAs, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway GAs, homologous recombination GAs, G1/S-cell cycle GAs, WNT pathway GAs, Fanconi anemia/interstrand crosslink repair (FA/ICL) repair pathway GAs, RAS/RAF/MEK pathway GAs (other than BRAF), mismatch repair GAs, and POLE mutations (see Figs 1C to 1F for details). Each column represents a single patient sample, and samples that harbored an alteration in each pathway are indicated in black. (C to F) GAs identified in each pathway, including the (C) PI3K/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, (D) G1/S-cell cycle pathway, (E) WNT pathway, and (F) RAS/RAF/MEK pathway (NF1 mutation, rearrangement, or copy number loss; BRAF or RAF1 mutations or rearrangements; ARAF, K/N/H-RAS, or MAP2K1/2 mutations were included); percent of altered cases is indicated. (G) Comparison of alteration frequencies for each gene in primary site samples versus metastatic site samples. The dotted line represents a 1:1 relationship. Genes that were enriched (difference between primary site v metastatic site frequency) by at least 2% are indicated (all P < .05 by Fisher’s exact test [two-tailed]), with genes enriched at least twofold indicated in red (all P < .001 by Fisher’s exact test [two-tailed]). Details are listed in Appendix Table A3. indel, insertion/deletion.

The PI3K/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway was frequently altered (40.8%; Figs 1B and 1C). As expected, PTEN GAs were frequent, and we observed activating mutations and amplifications in PIK3CA, PIK3CB, AKT1/2/3, MTOR, and RICTOR and loss-of-function alterations in PIK3R1/2 and TSC1/2. The G1/S-cell cycle pathway was altered in 23.4% of cases, most frequently RB1 loss-of-function alterations (9.7%), as well as copy number alterations (CNAs) in CDK4/6, CCND1/2/3, CCNE1, CDKN2A/B/C, and CDKN1B (Figs 1B and 1D). The WNT pathway was altered in 16.2% of cases (Figs 1B and 1E). RAS/RAF/MEK pathway alterations (5.7%; Figs 1B and 1F) included oncogenic BRAF mutations (Appendix Fig A2), BRAF/RAF1 rearrangements, activating mutations in RAF1/ARAF, KRAS/NRAS/HRAS and MAP2K1/2, and NF1 loss-of-function alterations. Homologous recombination repair (HRR)–related pathway alterations were observed in 23.4% of cases (Fig 1B), and other DNA repair pathway alterations included Fanconi anemia/interstrand crosslink repair (FA/ICL) genes (4.8%), CDK12 (5.6%), mismatch repair (MMR) genes (4.3%), and the DNA polymerase gene POLE (0.1%; Fig 1B).

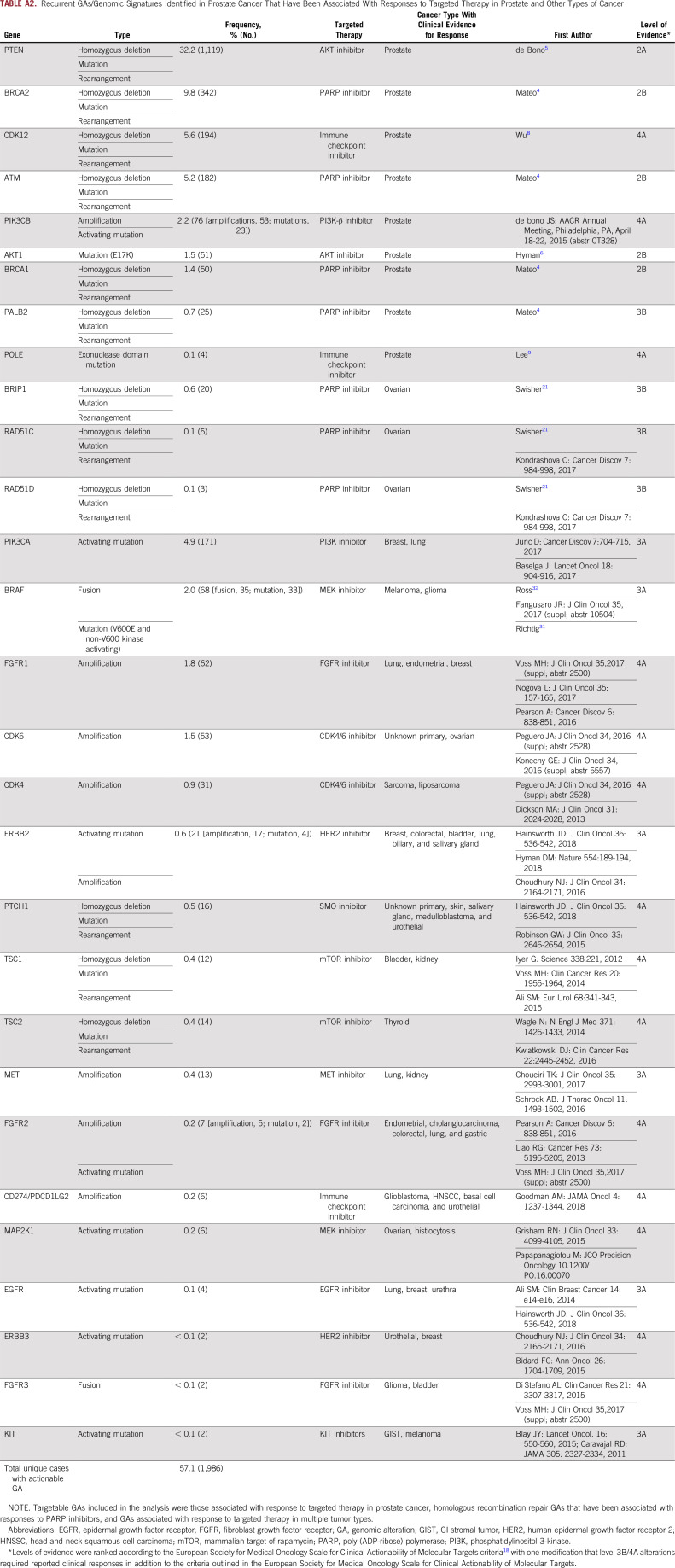

Overall, 57% of cases harbored GAs that are investigational biomarkers for targeted therapies with varying levels of supporting clinical evidence18 (Appendix Table A2), including candidate biomarkers for targeted therapies in advanced phases of development in prostate cancer (eg, PTEN, AKT1, BRCA1/2, ATM) and those that have been successfully targeted in other tumor types, such as activating BRAF and ERBB2 GAs.

Distinct genomic subsets of prostate cancer have been described, including those defined by ETS fusions, SPOP mutations, IDH1 mutations,1 and CDK12 GAs.8 Consistent with distinct subsets, ETS fusions were mutually exclusive with SPOP/CUL3 GAs (P < .001; Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed), CDK12 GA (P < .001), and BRAF rearrangements/mutations (P < .001; Fig 1B).

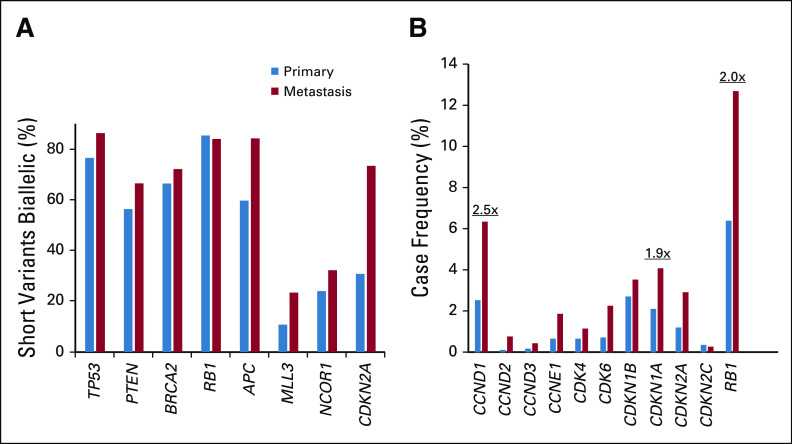

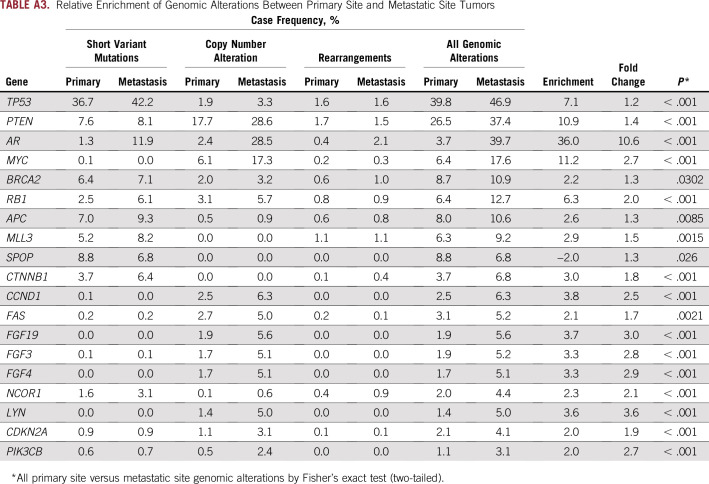

To compare primary and metastatic site tumors, we assessed relative enrichment in GAs (Fig 1G; Appendix Table A3). GAs enriched by 2% or more in metastatic site tumors included AR (36.0% enrichment), MYC (11.2%), PTEN (10.9%), TP53 (7.1%), RB1 (6.3%), the 11q13 amplicon (CCND1 [3.8%], FGF19 [3.7%], FGF3 [3.3%], FGF4 [3.3%]), LYN (3.6%), CTNNB1 (3.0%), MLL3 (2.9%), APC (2.6%), NCOR1 (2.3%), BRCA2 (2.2%), FAS (2.1%), PIK3CB (2.0%), and CDKN2A (2.0%; all P < .05). Of these, 10 were enriched in metastatic site tumors by twofold or more (all P < .001), including AR (10.6-fold), LYN (3.6-fold), 11q13 (CCND1 [2.5-fold], FGF19 [3.0-fold], FGF3 [2.8-fold], FGF4 [2.9-fold]), MYC (2.7-fold), NCOR1 (2.1-fold), PIK3CB (2.7-fold), and RB1 (2.0-fold overall, 1.8-fold for homozygous deletions, 2.5-fold for mutations). The fraction of tumor suppressor gene mutations predicted to result in biallelic inactivation was not higher in primary site tumors, which suggests that metastatic enrichments were functionally relevant (Appendix Fig A3A). Collectively, G1/S-cell cycle genes were altered in 30.7% of metastatic site versus 15.4% of primary site tumors (Appendix Fig A3B). The only gene enriched in primary site tumors was SPOP (2.0%; 1.3-fold enrichment; P = .03).

DNA Repair Pathway GAs

HRR and FA/ICL pathway GAs have been associated with responses to PARP inhibitors in prostate cancer,4 and CDK12 has been implicated in HRR in preclinical studies but also has distinct functions associated with DNA replication-related repair.19,20 Collectively, these genes were altered in 31.0% of cases (Figs 1B and 2A), and genes altered in more than 1% of cases included BRCA2 (9.8%), CDK12 (5.6%), ATM (5.2%), CHEK2 (1.8%), BRCA1 (1.4%), FANCA (1.3%), and ATR (1.1%). MMR pathway GAs10 or POLE V411L,9 which have been associated with increased TMB and responses to immunotherapy, were observed in 4.3% and 0.1% of cases, respectively (Fig 2B).

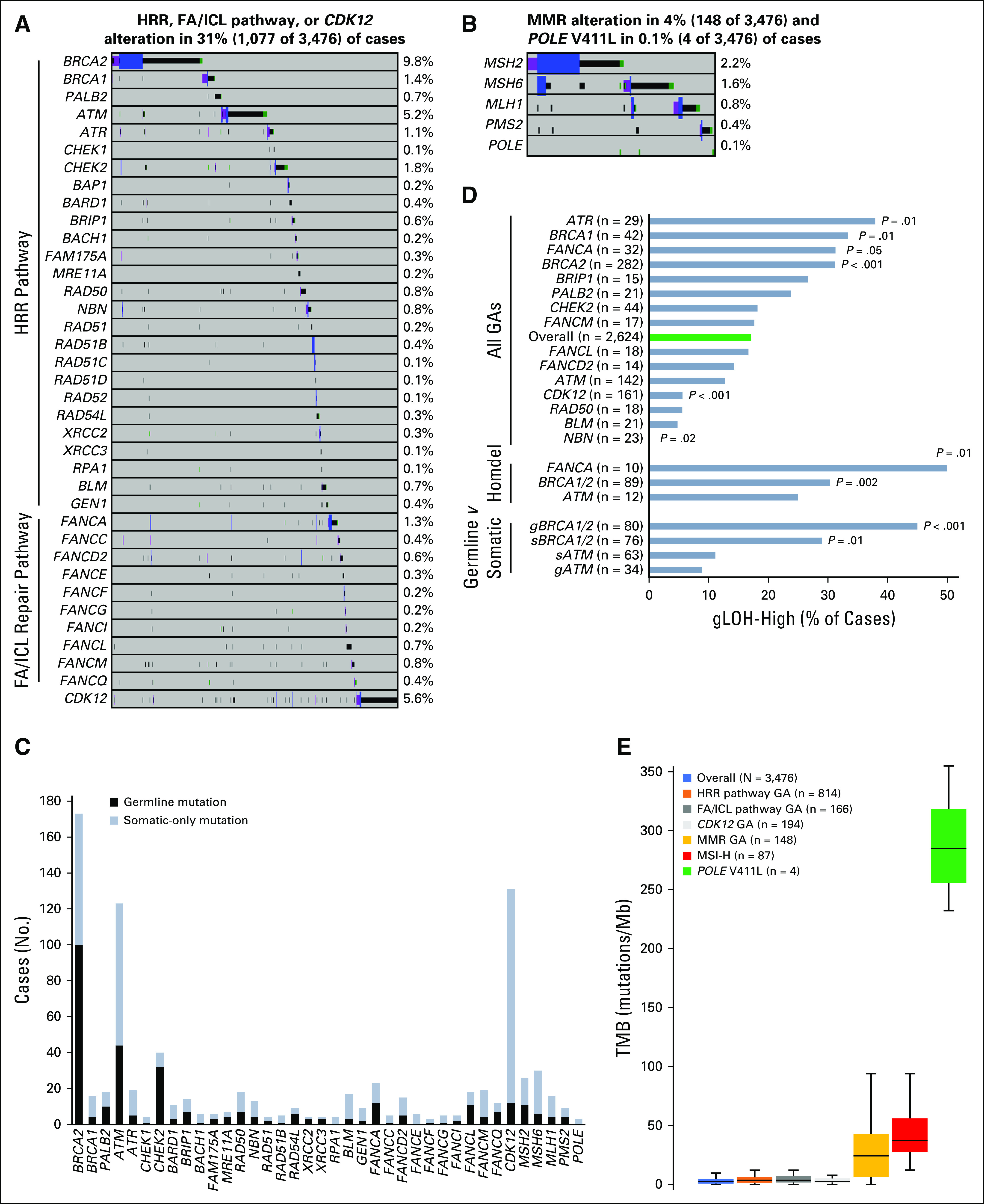

FIG 2.

DNA repair genomic alterations (GAs) and association with genomic signatures. GAs identified in the (A) homologous recombination repair (HRR) pathway, Fanconi anemia/interstrand crosslink repair (FA/ICL) repair pathway, and CDK12 or (B) mismatch repair (MMR; MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, PMS2) or polymerase (POLE) V411L genes. (C) Mutations in DNA repair genes were assessed for germline or somatic status. For each gene, the number of cases with a germline mutation or somatic-only mutation is shown. (D) Genome-wide loss of heterozygosity (gLOH) score was evaluated for the overall data set (blue) and for association with each DNA repair gene altered at 0.5% or greater frequency. The frequency of cases with a gLOH-high score for each subset is shown. The term “all GAs” represents the association with any reportable GA (short variant mutation, homozygous deletion or rearrangement) in the specified gene. Homozygous deletions (homdel) were individually assessed for BRCA1/2, ATM, and FANCA. Germline (g) and somatic (s) mutations were individually assessed for BRCA1/2 and ATM. Each subset was individually compared with the overall data set, and unadjusted P values are shown (Fisher’s exact test [two-tailed]). (E) Tumor mutational burden (TMB) was evaluated for the overall data set and compared with various genomic subsets, including those harboring an HRR pathway GA, an FA/ICL pathway GA, a CDK12 GA, an MMR GA, a microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) genomic signature, or a POLE V411L mutation. Box and whisker plots: Boxes span first and third quartiles, the median is denoted by the horizontal line in the box, and whiskers indicate maximum and minimum values within 1.5× the interquartile range.

Germline/somatic status predictions17 were made to estimate the prevalence of germline DNA repair mutations; 933 of 1,261 of DNA repair mutations (74%) yielded an available germline/somatic call of which 35.7% were germline (Fig 2C). Predicted germline mutations were identified in 57.8% of BRCA2-, 25.0% of BRCA1-, 35.8% of ATM-, 80.0% of CHEK2-, 52.2% of FANCA-, 42.3% of MSH2-, 20.0% of MSH6-, 25.0% of MLH1-, and 44.4% of PMS2-mutated cases; only 9.2% of CDK12-mutated cases harbored a predicted germline mutation (Fig 2C).

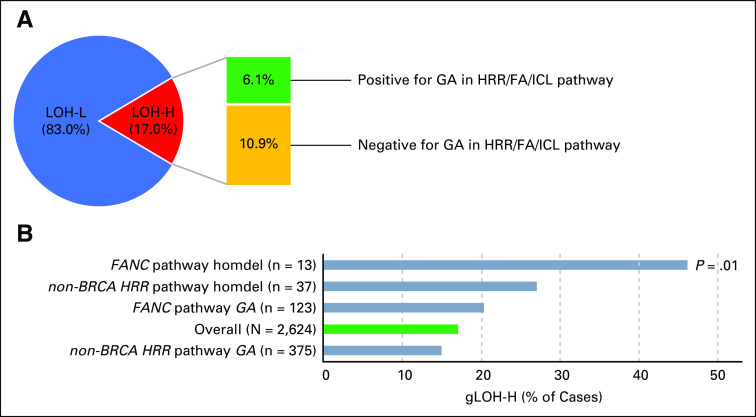

Genomic Signatures: gLOH

In addition to GAs in individual DNA repair genes, genomic signatures represent the phenotypic readout of deleterious DNA repair and are potential predictive biomarkers. For example, gLOH is a measure of homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) and is associated with PARP inhibitor clinical benefit in BRCA1/2 wild-type ovarian cancer.21,22 We assessed the association between genomic signatures and DNA repair GAs.

Percent gLOH was assessable for 2,624 cases, and the median gLOH score was 8.5% (interquartile range, 5.8%-12.2%). Overall, 447 of 2,624 cases (17%) were gLOH high (gLOH-H; Fig 2D), of which 35.9% harbored an HRR or FA/ICL pathway GA (Appendix Fig A4A). We evaluated the association between gLOH and DNA repair GAs (Fig 2D). Consistent with the established relationship between BRCA1/2 and HRD,21 BRCA1/2-altered cases (both predicted germline and somatic mutations) were more frequently gLOH-H compared with the overall data set (Fig 2D).

To evaluate the potential relevance of non-BRCA1/2 DNA repair genes as biomarkers for PARP inhibition, we assessed their association with gLOH. gLOH-H frequency was comparable between the overall data set and cases with non-BRCA1/2 DNA repair GAs, although cases with homozygous deletions in non-BRCA1/2 HRR pathway or FA/ICL pathway genes were more frequently gLOH-H (Appendix Fig A4B). While considering each gene individually, cases with ATR or FANCA GA (particularly FANCA homozygous deletion) were more frequently gLOH-H, whereas CDK12- or NBN-altered cases were significantly less frequently gLOH-H (Fig 2D).

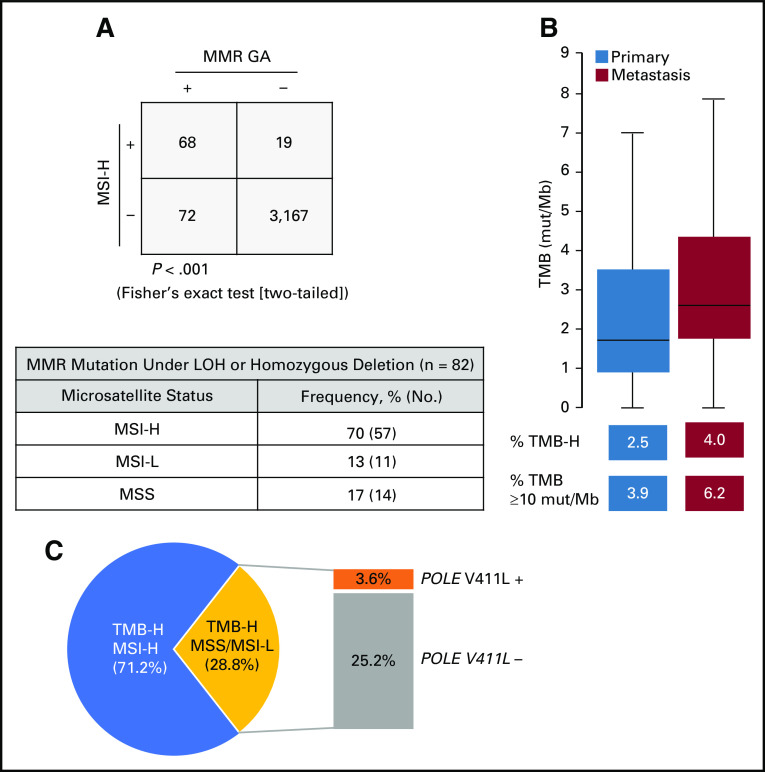

Genomic Signatures: TMB and MSI

MSI-H and TMB-H genomic signatures are biomarkers of sensitivity to immunotherapies23,24; therefore, we evaluated the association between MSI/TMB and MMR/polymerase pathway GAs. MSI status was assessable for 3,326 cases, and overall, 87 of 3,326 of cases (2.6%) were MSI-H (2.0% primary site, 3.1% metastatic site tumors). MSI-H status significantly co-occurred with MMR GA, with 78.2% MSI-H cases also harboring a GA in the MMR pathway. For cases with an MMR GA, 48.6% were MSI-H; for the subset of MMR mutations resulting in biallelic inactivation, 69.5% were MSI-H (Appendix Fig A5A).

Deleterious MMR or POLE GAs can cause an accumulation of mutations that can be quantitatively measured by TMB. Median TMB was low overall (2.6 mutations/Mb) and low for primary site and metastatic site tumors; a subset of cases (3.3%) was TMB-H (≥ 20 mutations/Mb), including 2.5% of primary site and 4.0% of metastatic site tumors (Appendix Fig A5B). At a lower TMB threshold,25 5.1% of cases overall had 10 mutations/Mb or more (Appendix Fig A5B). TMB was significantly increased for cases with MMR GA (median, 24.4 mutations/Mb) and MSI-H (median, 37.4 mutations/Mb); median TMB for POLE V411L–mutated cases was 285 mutations/Mb (Fig 2E). As expected, median TMB was low for cases with GA in other DNA repair pathways (Fig 2E). For cases with an HRR GA, the frequency of TMB-H was higher (9.3%) than the overall data set (3.3%); however, homozygous deletions in HRR pathway genes and gLOH-H score were not associated with TMB-H, which suggests that HRD is likely not causal for the TMB-H phenotype.

For 111 TMB-H cases with assessable MSI status, the TMB-H phenotype was explained by concurrent MSI-H status for 71.2% of cases and by POLE V411L mutation for 3.6% of cases (Appendix Fig A5C). For the remaining cases, TMB-H phenotype was not attributed to MSI-H or POLE.

Landscape of ETS Fusions and AR GAs

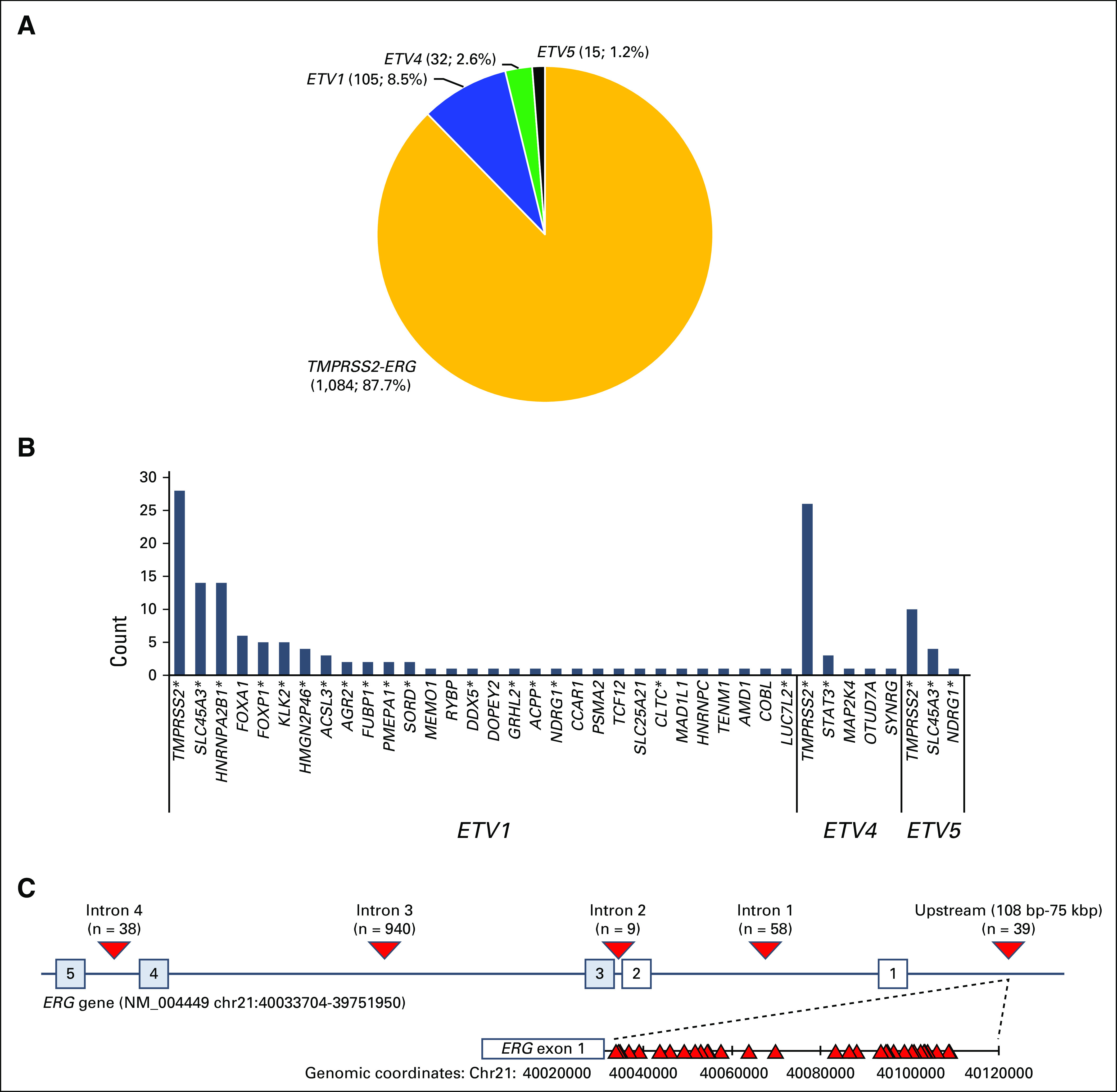

In total, 1,236 ETS fusions were detected (one sample harbored two ETS fusions; Fig 1B). TMPRSS2-ERG comprised the majority (87.7%) of ETS fusions (Fig 3A), with the remaining consisting of ETV1 (8.5%), ETV4 (2.6%), and ETV5 (1.2%) with diverse fusion partners, including several not previously described (Fig 3B). Consistent with previous studies, breakpoints were most frequently in ERG intron 326 (Fig 3C). We also identified breakpoints that juxtaposed TMPRSS2 with the intergenic region upstream of ERG (0.1 to 75 kb upstream; Fig 3C); similar upstream intergenic breakpoints were observed for TMPRSS2 fusions with ETV4 (10 of 32 cases) and ETV5 (two of 15 cases).

FIG 3.

TMPRSS2-ERG and other ETS fusions. (A) Distribution of 1,236 ETS fusions in this study. (B) The 5′ partner genes are identified. (C) Distribution of breakpoints identified in the ERG gene. Numbered boxes represent exons. Triangles represent observed breakpoints. (*) Fusion partners that have been previously described. bp, base pair; kbp, kilobase pair.

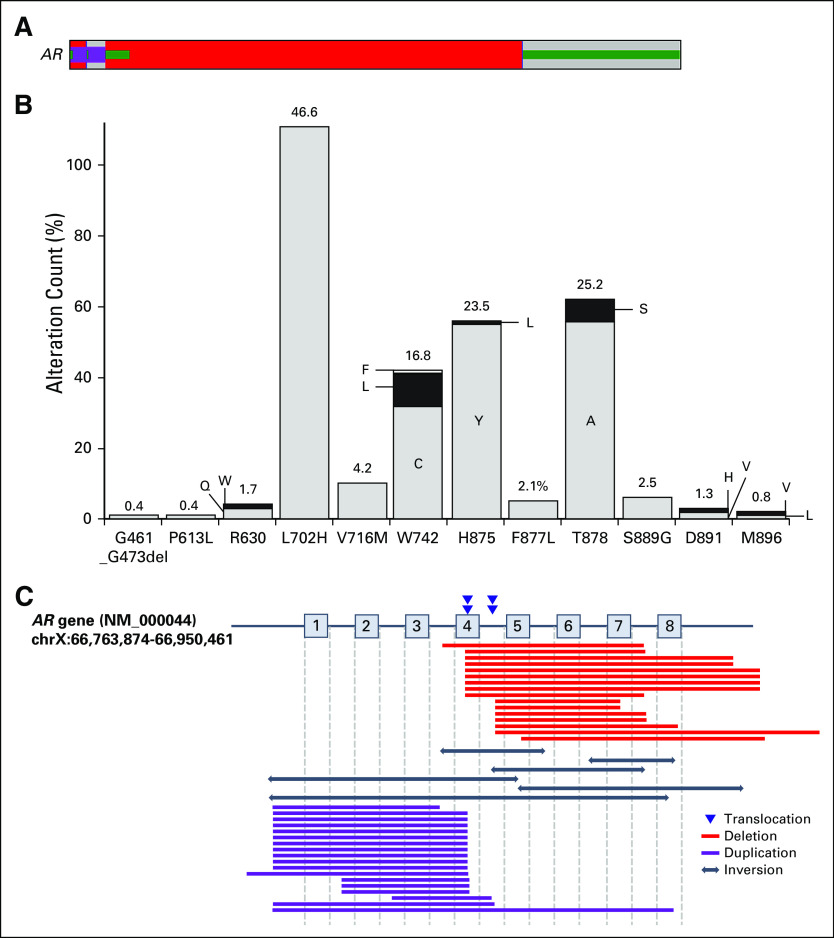

AR GAs are associated with castration-resistant disease and were most enriched in metastatic site tumors (39.7% of metastatic site and 3.7% of primary site tumors; Fig 1G). In total, 905 AR GAs were observed in 783 cases (557 CNAs, 303 mutations, and 45 rearrangements; Fig 4A). CNAs were observed in 16.0% of cases (2.4% primary site and 28.5% metastatic site). Five hundred fifty-five of 557 CNAs were amplifications (median copy number, 24; range, six to 366); two homozygous deletions that encompass exons 5 to 7 or exons 5 to 8 are likely activating.27 AR missense mutations were observed in 6.9% of cases (1.3% primary site and 11.9% metastatic site), and most were ligand-binding domain antiandrogen resistance mutations (Fig 4B).28 Finally, AR rearrangements were observed in 1.3% of cases (0.4% primary site and 2.2% metastatic site); however, because the sequencing strategy was not explicitly designed to detect AR rearrangements and does not fully cover AR intronic regions, the true frequency of AR rearrangements is difficult to establish. The 45 rearrangements included 18 duplications, 17 deletions, six inversions, and four translocations that were predicted to result in a truncated AR gene retaining exons 1 to 3 that encode the DNA binding domain (Fig 4C); such alterations are likely activating.27,29

FIG 4.

Landscape of AR alterations. (A) AR genomic alterations (GAs) were identified in 721 cases, including amplification (red), mutation (green), and rearrangements (purple). (B) Graph that represents the number of cases with each AR GA. The percentages indicate the frequency of AR mutations at each codon as a fraction of all AR mutations. Letters denote amino acid abbreviations as recommended by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. (C) Map of AR rearrangements that describe breakpoints for translocations and deleted, duplicated, or inverted regions.

DISCUSSION

CGP of 3,476 prostate tumors identified frequent GAs in the PI3K, cell cycle, HRR, and WNT pathways and diverse GAs that are investigational biomarkers for targeted therapies in 57% of cases (Appendix Table A2). GAs that co-occur with targetable GAs (Fig 1B) and their impact on response to therapy warrant consideration in biomarker-driven trials. MSI-H and TMB-H have been associated with immunotherapy benefit,10,24,25 and gLOH-H has been associated with PARP inhibitor benefit21; therefore, assessment of signatures of genomic instability potentially expands the population of patients addressable with immunotherapy or targeted therapy.

We identified a subset of TMPRSS2 rearrangements fused to upstream intergenic regions of ERG, ETV4, or ETV5 as well as novel ETS fusion partners. However, the assay is limited to common breakpoints and may incompletely identify rare ETS fusions with novel breakpoints. Consistent with distinct molecular subsets of prostate cancer,1,8 ETS fusions were mutually exclusive with SPOP/CUL3, CDK12 mutations, or BRAF rearrangements/mutations that may potentially comprise a clinically relevant genomic subset.30,31

Diverse AR GAs can mediate androgen axis inhibitor resistance28,29 and were strongly enriched in metastatic site tumors. AR rearrangements that disrupted the ligand-binding domain can mediate resistance to current AR inhibitors.29 Development of novel AR inhibitors that target the diverse spectrum of AR alterations is needed. AR GAs commonly co-occurred with alterations in other targetable pathways (Fig 1B); such concurrent alterations may present an opportunity for targeted therapy in androgen axis inhibitor–resistant tumors.

In addition to metastatic enrichment in AR GAs, we identified first that CCND1/FGF3/FGF4/FGF19 (11q13) amplifications were enriched in metastatic sites. Of note, 11q13 amplification is associated with endocrine resistance in breast cancer and potentially targetable by fibroblast growth factor receptor inhibitors32-34 and, therefore, warrants investigation in prostate cancer. Second, CDKN2A GAs were enriched in metastatic site tumors (1.9-fold), and although not previously described in primary versus metastatic studies,1-3 acquired CDKN2A alterations were described in enzalutamide-resistant tumors.15 Metastatic enrichment of cell cycle GAs suggests that CDK4/6 inhibitors could be explored. Third, NCOR1 GAs were enriched in metastatic site tumors. Downregulation of NCOR1, which encodes a negative regulator of AR, is associated with androgen axis inhibitor resistance.35 Finally, we independently confirmed1-3 metastatic site enrichment of MYC, PTEN, TP53, RB1, CTNNB1, MLL3, APC, BRCA2, and PIK3CB and primary site enrichment of SPOP.

DNA repair pathway GAs are associated with responses to PARP inhibitors or immunotherapy in many solid tumor types.4,10 Collectively, HRR, FA/ICL, CDK12, or MMR/DNA polymerase genes were altered in 32.6% of cases. On the basis of a germline/somatic prediction algorithm,17 we estimate that 35.7% of DNA repair gene mutations were germline. Current guidelines (National Comprehensive Cancer Network version 4.2018)36 recommend testing for certain HRR genes, MMR genes, or MSI status; identification of such DNA repair GA by tumor sequencing warrants follow-up germline testing and genetic counseling. A limitation of tumor-only sequencing is that germline/somatic calls are not definitive and require confirmation by dedicated germline testing. However, compared with a recent study,3 we identify similar relative proportions of germline/somatic mutations for frequently mutated HRR genes (BRCA2, ATM, CHEK2). Furthermore, another study of prostate cancer similarly identified germline mutations for many of the DNA repair genes evaluated here.37 We also describe potential CDK12 germline mutations (four of 12 were rs138292741). Although not identified in one recent study of CDK12 in prostate cancer,8 germline truncating CDK12 mutations were described in other studies, including prostate cancer,38-40 and in germline databases.40

Although preclinical studies have identified non-BRCA1/2 HRR genes, their association with HRD phenotype in clinical samples is unclear. As expected, BRCA1/2 was associated with gLOH-H. Beyond BRCA1/2, associations with gLOH-H were observed for ATR and FANCA. CDK12 is a candidate biomarker for PARP inhibition4 on the basis of preclinical studies19,20; however, gLOH-H was significantly less frequent for CDK12-altered cases; this finding is consistent with recent studies suggesting that CDK12 GAs are associated with a focal tandem duplication phenotype that is distinct from HRD.8,41,42 In trials for metastatic prostate cancer, germline or somatic BRCA1/2 alterations were associated with response to PARP inhibitor monotherapy.4,43 In contrast, non-BRCA HRR genes have been less consistent in predicting response4,43,44 and require further refinement in clinical trials.

The evaluation of both individual GAs and genomic signatures together may be important when exploring predictive biomarkers. Identification of gLOH-H cases lacking DNA repair GAs (Appendix Fig A4A) may have clinical value, but further investigation in PARP inhibitor trials is required to assess the clinical utility of gLOH as a biomarker in prostate cancer. Similarly, DNA repair GAs were associated with MSI-H or TMB-H genomic signatures that are associated with benefit from immunotherapy (Fig 2; Appendix Fig A5). A subset of MSI/TMB-H cases do not harbor corresponding DNA repair GAs potentially because GAs may occur in genes involved in DNA repair that have not yet been discovered, complex rearrangements with intronic breakpoints may be challenging to detect, or genomic instability can occur through mechanisms such as gene silencing or extrinsic DNA damage.

Limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, limited access to patient-level clinical data prevented further subclassification of primary and metastatic samples by castration resistance status. Furthermore, because samples were collected for routine clinical testing, primary samples in this cohort may be biased toward patients who have received prior treatment or developed metastatic disease that resulted in a distinct genomic landscape from untreated primary tumors. In contrast, metastatic samples may not all represent castration-resistant disease. Therefore, sensitivity to identify genomic associations with primary/aggressive disease may be reduced. However, many findings in this study recapitulated those described in previous studies of smaller cohorts with better clinical annotation that compared metastatic castration-resistant tumors with noncastrate primary site tumors.2,3,13 Particularly, the low AR GA frequency in primary site samples is consistent with mostly noncastrate disease, and the high AR GA frequency in metastatic site samples is consistent with mostly castration-resistant disease.2 Second, in contrast to whole-exome sequencing studies of prostate cancer, this study uses an assay that is used in routine clinical practice and was therefore limited to the 395 genes assessed.

In this study, routine CGP for prostate cancer identified frequent alterations in genes and pathways as well as in genomic signatures. These findings may suggest routes to targeted therapy or immunotherapy for patient’s refractory to current therapies.

Appendix

Methods

Approval for this study, including a waiver of informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act waiver of authorization, was obtained from the Western Institutional Review Board (protocol 20152817). Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) results were reported clinically by prospective sequencing of tissue samples from 3,476 unique patients with prostate cancer (August 2014 to February 2018) using a validated hybrid capture-based CGP assay (FoundationOne [baitset version T7 was used during this period])16 in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified, College of American Pathologists–accredited, New York State–approved laboratory (Foundation Medicine, Cambridge, MA). For patients with multiple submitted samples, only a single sample was included, and the sample with the highest sequencing quality metrics was included. Age and site of specimen collection were abstracted from the accompanying pathology reports, clinical notes, and requisition forms submitted by the treating physician. Specimens included 1,660 primary site tumors and 1,816 metastatic site tumors (Appendix Fig A1). The pathologic diagnosis of each case was confirmed on routine hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides, and all samples forwarded for DNA extraction contained a minimum of 20% tumor nuclei. CGP was performed on hybridization-captured, adaptor ligation-based libraries to a median coverage depth of 743× for 395 cancer-related genes plus select introns from 31 genes frequently rearranged in cancer (Appendix Table A1). For ETS fusions, targeted regions were TMPRSS2 (introns 1 to 3), ERG (all exons), ETV1 (introns 3 to 4), ETV4 (intron 8), and ETV5 (introns 6 to 7).

Results were analyzed for base substitutions, short insertions/deletions, rearrangements, and copy number alterations (amplification and homozygous deletion). Custom filtering was applied to remove benign germline events as previously described (Hartmaier et al: Cancer Res 77:2464-2475, 2017). Genomic alterations (GAs) were called as reportable if the specific variant was present in the Catalog of Somatic Mutations in Cancer database (Forbes et al: Nucleic Acids Res 45:D777-D783, 2017), if the variant has been characterized as pathogenic, or if the variant had likely functional status (disruptive alterations in tumor suppressor genes); all other variants were classified as variants of unknown significance.

To compare relative enrichments in primary site and metastatic site tumors, genes altered at a 2% or greater frequency were assessed for enrichment. Enrichment was defined as the difference in frequency of gene alteration between metastatic site and primary site samples.

To determine microsatellite instability status, 114 intronic homopolymer repeat loci on the FoundationOne panel were analyzed for length variability and compiled into an overall microsatellite instability score through principal components analysis (Chalmers et al: Genome Med 9:34, 2017). Tumor mutational burden was calculated as the number of somatic base substitutions or insertions/deletions per megabase of the coding region target territory of the test (1.1 Mb) after filtering to remove known somatic and deleterious mutations and extrapolating that value to the exome or genome as a whole (Chalmers et al: Genome Med 9:34, 2017). Tumor mutational burden was categorized as low (fewer than six mutations/Mb), intermediate (six to 20 mutations/Mb), or high (20 mutations/Mb or more; Chalmers et al: Genome Med 9:34, 2017). Germline, somatic, and zygosity statuses for mutations were determined without matched normal tissue as previously described17; in validation testing of 480 germline/somatic calls from tumor-only sequencing with matched normal reference samples, accuracy was 95% for somatic calls and 99% for germline calls. Biallelic inactivation was defined as mutations under loss of heterozygosity (LOH) as determined by zygosity status.17 Percent genome-wide LOH (gLOH) was used as a marker of homologous recombination deficiency and calculated as described, and a gLOH score of 14% or greater was defined as gLOH-high.21 Potentially targetable GAs were defined as those that have been associated with response to targeted therapy in prostate cancer, homologous recombination repair GAs that have been associated with responses to poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors, or GAs associated with response to targeted therapy in multiple other tumor types and were ranked according to modified European Society for Medical Oncology Scale for Clinical Actionability of Molecular Targets criteria.18

FIG A1.

(A) Distribution of sites of sample collection (prostate, 47.8%; distant lymph node [LN (D)], 12.4%; regional LN [LN (R)], 3.7%; unspecified LN [LN (unk)], 0.3%; liver, 13.2%; bone, 10.0%; lung, 2.7%; other metastatic, 9.9%). (B) Distribution of prostate histologic types.

FIG A2.

Details of the BRAF rearrangements, RAF1 rearrangements, and BRAF short variant mutations. The diagram illustrates BRAF (top) and RAF1 (bottom) rearrangements, including fusions, N-terminal deletions, and kinase domain duplications. Exons are numbered. For fusion, exons (e) are annotated with the last exon included in the 5′ partner and the first exon included in the 3′ partner. In addition, BRAF rearrangements at intron 9 (n = 6) and intron 7 (n = 1) and RAF1 rearrangement at intron 7 with no clear fusion partner were identified (data not shown). The table lists the 43 BRAF mutations identified.

FIG A3.

(A) For metastasis-enriched tumor suppressor genes (see Fig 1G), short variant mutations were assessed for loss of heterozygosity. Frequency of short variant mutations under loss of heterozygosity (biallelic) is shown. (B) Frequency of genomic alterations for individual genes in G1/S-cell cycle pathway in primary versus metastatic site samples. Fold change is indicated.

FIG A4.

(A) Genome-wide loss of heterozygosity (gLOH) score was assessable for 2,624 cases, and cases with 14% or more gLOH were designated LOH-high (LOH-H). All other cases were LOH-low (LOH-L). LOH-H cases were assessed for the presence (green) or absence (yellow) of a genomic alteration (GA) in the homologous recombination repair (HRR) or Fanconi anemia/interstrand crosslink repair (FA/ICL) pathway. (B) Genes were grouped together into HRR pathway (excluding non-BRCA1/2) or FA/ICL pathway (FANC); genes were categorized as in Figure 2A. All GAs or only homozygous deletions (homdel) were assessed for LOH-H and compared with the overall data set (green). Each subset was individually compared with the overall data set, and unadjusted P values are shown (Fisher’s exact test [two-tailed]).

FIG A5.

(A) Microsatellite instability (MSI) status was assessable for 3,326 cases, and each case was designated as MSI-high (MSI-H), MSI-low (MSI-L), or microsatellite stable (MSS). MSI-H cases were assessed for the presence or absence of mismatch repair (MMR) genomic alterations (GAs). MSI-H or MMR GA–positive samples are indicated with a plus sign, and negative samples are indicated with a minus sign. Of the cases where both MSI status and MMR GA zygosity status could be determined, 82 cases had MMR GA that resulted in loss of function of both alleles (microsatellite status in this subset listed in table). (B) Tumor mutational burden (TMB) was evaluated for primary site and metastatic site cases. Box and whisker plots: Boxes span first and third quartiles, the median is denoted by the horizontal line in the box, and whiskers indicate maximum and minimum values with 1.5× the interquartile range. The percent TMB-high (TMB-H) or TMB of 10 or more mutations (mut)/Mb cases in primary site and metastatic site tumors is indicated. (C) TMB-H samples were assessed for whether they were MSI-H or MSS/MSI-L. TMB-H cases that were not MSI-H also were assessed for POLE V411L pathogenic mutations.

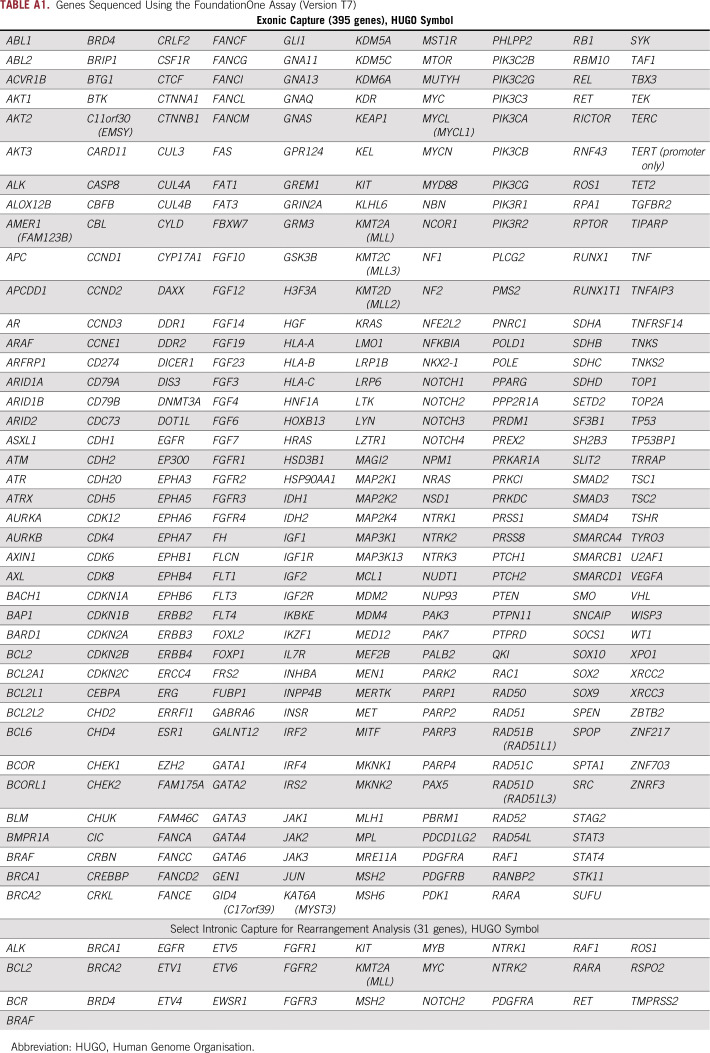

TABLE A1.

Genes Sequenced Using the FoundationOne Assay (Version T7)

TABLE A2.

Recurrent GAs/Genomic Signatures Identified in Prostate Cancer That Have Been Associated With Responses to Targeted Therapy in Prostate and Other Types of Cancer

TABLE A3.

Relative Enrichment of Genomic Alterations Between Primary Site and Metastatic Site Tumors

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Jon H. Chung, Ninad Dewal, Gennady Bratslavsky, Sumanta K. Pal, Jeffrey S. Ross, Siraj M. Ali, Neeraj Agarwal

Financial support: Jeffrey P. Gregg

Administrative support: Vincent A. Miller

Provision of study material or patients: Primo Lara Jr

Collection and assembly of data: Jon H. Chung, Robert Whitehead, Garrett M. Frampton, Gennady Bratslavsky, Sumanta K. Pal, Jeffrey P. Gregg, Jeffrey S. Ross, Siraj M. Ali

Data analysis and interpretation: Jon H. Chung, Ninad Dewal, Ethan Sokol, Paul Mathew, Sherri Z. Millis, Garrett M. Frampton, Gennady Bratslavsky, Sumanta K. Pal, Richard J. Lee, Andrea Necchi, Jeffrey P. Gregg, Primo Lara Jr, Emmanuel S. Antonarakis, Vincent A. Miller, Jeffrey S. Ross, Siraj M. Ali

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/po/authorcenter.

Jon H. Chung

Employment: Foundation Medicine

Ninad Dewal

Employment: Foundation Medicine

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Foundation Medicine

Ethan Sokol

Employment: Foundation Medicine

Paul Mathew

Honoraria: Exelixis

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Patent pending on new therapeutic invention

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Exelixis

Robert Whitehead

Employment: UnitedHealthcare, Cancer Treatment Centers of America

Sherri Z. Millis

Employment: Foundation Medicine

Garrett M. Frampton

Employment: Foundation Medicine

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Foundation Medicine

Sumanta K. Pal

Honoraria: Novartis, Medivation, Astellas Pharma

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Novartis, Aveo, Myriad Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Exelixis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Astellas Pharma, Ipsen, Eisai

Research Funding: Medivation

Richard J. Lee

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Exelixis

Research Funding: Janssen Pharmaceuticals

Andrea Necchi

Employment: Bayer AG (I)

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Bayer AG (I)

Honoraria: Roche, Merck, AstraZeneca, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Foundation Medicine

Consulting or Advisory Role: Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche, Bayer AG, AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Incyte, Seattle Genetics, Astellas Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Rainier Therapeutics

Research Funding: Merck Sharp & Dohme (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Roche, Merck Sharp & Dohme, AstraZeneca, Janssen Pharmaceuticals

Other Relationship: Bayer AG (I)

Jeffrey P. Gregg

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Foundation Medicine

Speakers’ Bureau: AstraZeneca, Foundation Medicine, Bristol-Myers Squibb

Primo Lara Jr

Honoraria: Pfizer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Exelixis, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Bayer AG, Genentech, Roche, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AbbVie, Turnstone Bio, Foundation Medicine, Merck, CellMax Life, Nektar

Research Funding: Millennium Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Polaris (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Aragon Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Janssen Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Heat Biologics (Inst), TRACON Pharma (Inst), Merck (Inst), Pharmacyclics (Inst), Incyte (Inst)

Emmanuel S. Antonarakis

Honoraria: Sanofi, Dendreon, Medivation, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, ESSA, Astellas Pharma, Merck, AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology

Consulting or Advisory Role: Sanofi, Dendreon, Medivation, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, ESSA, Astellas Pharma, Merck, AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology

Research Funding: Janssen Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Johnson & Johnson (Inst), Sanofi (Inst), Dendreon (Inst), Aragon Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Exelixis (Inst), Millennium Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), Tokai Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Merck (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Clovis Oncology (Inst), Constellation Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Co-inventor of a biomarker technology that has been licensed to QIAGEN

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Sanofi, Dendreon, Medivation

Vincent A. Miller

Employment: Foundation Medicine

Leadership: Foundation Medicine

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Foundation Medicine

Consulting or Advisory Role: Revolution Medicines

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Receive periodic royalties related to T790M patent awarded to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

Jeffrey S. Ross

Employment: Foundation Medicine

Leadership: Foundation Medicine

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Foundation Medicine

Research Funding: Foundation Medicine

Siraj M. Ali

Employment: Foundation Medicine

Leadership: Incysus

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Exelixis, Blueprint Medicines, Agios, Genocea Biosciences

Consulting or Advisory Role: Revolution Medicines, Azitra (I), Princepx Tx (I)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Patents through Foundation Medicine, patents through Seres Health on microbiome studies in non-neoplastic disease (I)

Neeraj Agarwal

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Exelixis, Medivation, Astellas Pharma, Eisai, Merck, Novartis, EMD Serono, Clovis Oncology, Genentech, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Nektar, Eli Lilly, Bayer AG, Foundation Medicine, Argos Therapeutics

Research Funding: Bayer AG (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Medivation (Inst), Takeda Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), BN ImmunoTherapeutics (Inst), TRACON Pharma (Inst), Rexahn Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Amgen (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Active Biotech (Inst), Bavarian Nordic (Inst), Calithera Biosciences (Inst), Celldex (Inst), Eisai (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Immunomedics (Inst), Janssen Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Merck (Inst), NewLink Genetics (Inst), Prometheus (Inst), Sanofi (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abeshouse A, Ahn J, Akbani R. et al., editors. The molecular taxonomy of primary prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;163:1011–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armenia J, Wankowicz SAM, Liu D. et al., editors. The long tail of oncogenic drivers in prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2018;50:645–651. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0078-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abida W, Armenia J, Gopalan A. et al., editors. Prospective genomic profiling of prostate cancer across disease states reveals germline and somatic alterations that may affect clinical decision making. JCO Precis Oncol. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00029. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S. et al., editors. DNA-repair defects and olaparib in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1697–1708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Bono JS, De Giorgi U, Massard C, et al. PTEN loss as a predictive biomarker for the Akt inhibitor ipatasertib combined with abiraterone acetate in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) Ann Oncol. 2016;27:7180. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyman DM, Smyth LM, Donoghue MTA, et al. AKT inhibition in solid tumors with AKT1 mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2251–2259. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mateo J, Ganji G, Lemech C, et al. A first-time-in-human study of GSK2636771, a phosphoinositide 3 kinase beta-selective inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:5981–5992. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu Y-M, Cieślik M, Lonigro RJ, et al. Inactivation of CDK12 delineates a distinct immunogenic class of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2018;173:1770–1782.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee L, Ali S, Genega E, et al. Aggressive-variant microsatellite-stable POLE mutant prostate cancer with high mutation burden and durable response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2:1–8. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357:409–413. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson DR, Wu Y-M, Lonigro RJ, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of metastatic cancer. Nature. 2017;548:297–303. doi: 10.1038/nature23306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wedge DC, Gundem G, Mitchell T, et al. Sequencing of prostate cancers identifies new cancer genes, routes of progression and drug targets. Nat Genet. 2018;50:682–692. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0086-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu Y-M, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;161:1215–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.001. [Erratum: Cell 162:454, 2015] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joseph JD, Lu N, Qian J, et al. A clinically relevant androgen receptor mutation confers resistance to second-generation antiandrogens enzalutamide and ARN-509. Cancer Discov. 2013 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han GC, Hwang J, Wankowicz SAM, et al. Genomic resistance patterns to second-generation androgen blockade in paired tumor biopsies of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00140. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frampton GM, Fichtenholtz A, Otto GA, et al. Development and validation of a clinical cancer genomic profiling test based on massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:1023–1031. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun JX, He Y, Sanford E, et al. A computational approach to distinguish somatic vs. germline origin of genomic alterations from deep sequencing of cancer specimens without a matched normal. PLOS Comput Biol. 2018;14:e1005965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mateo J, Chakravarty D, Dienstmann R, et al. A framework to rank genomic alterations as targets for cancer precision medicine: The ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability of molecular Targets (ESCAT) Ann Oncol. 2018;29:1895–1902. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bajrami I, Frankum JR, Konde A, et al. Genome-wide profiling of genetic synthetic lethality identifies CDK12 as a novel determinant of PARP1/2 inhibitor sensitivity. Cancer Res. 2014;74:287–297. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blazek D, Kohoutek J, Bartholomeeusen K, et al. The cyclin K/Cdk12 complex maintains genomic stability via regulation of expression of DNA damage response genes. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2158–2172. doi: 10.1101/gad.16962311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swisher EM, Lin KK, Oza AM, et al. Rucaparib in relapsed, platinum-sensitive high-grade ovarian carcinoma (ARIEL2 Part 1): An international, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:75–87. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30559-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coleman RL, Oza AM, Lorusso D, et al. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390:1949–1961. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32440-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carbone DP, Reck M, Paz-Ares L, et al. First-line nivolumab in stage IV or recurrent non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2415–2426. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodman AM, Kato S, Bazhenova L, et al. Tumor mutational burden as an independent predictor of response to immunotherapy in diverse cancers. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16:2598–2608. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu T-E, Pluzanski A, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in lung cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N Engl J Med. 2018;376:2093–2104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adamo P, Ladomery MR. The oncogene ERG: A key factor in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2016;35:403–414. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nyquist MD, Li Y, Hwang TH, et al. TALEN-engineered AR gene rearrangements reveal endocrine uncoupling of androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:17492–17497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308587110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lallous N, Volik SV, Awrey S, et al. Functional analysis of androgen receptor mutations that confer anti-androgen resistance identified in circulating cell-free DNA from prostate cancer patients. Genome Biol. 2016;17:10. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0864-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henzler C, Li Y, Yang R, et al. Truncation and constitutive activation of the androgen receptor by diverse genomic rearrangements in prostate cancer. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13668. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richtig G, Hoeller C, Kashofer K, et al. Beyond the BRAFV600E hotspot: Biology and clinical implications of rare BRAF gene mutations in melanoma patients. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:936–944. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross JS, Wang K, Chmielecki J, et al. The distribution of BRAF gene fusions in solid tumors and response to targeted therapy. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:881–890. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giltnane JM, Hutchinson KE, Stricker TP, et al. Genomic profiling of ER+ breast cancers after short-term estrogen suppression reveals alterations associated with endocrine resistance. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaai7993. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aai7993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luen SJ, Asher R, Lee CK, et al. Association of somatic driver alterations with prognosis in postmenopausal, hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative early breast cancer: A secondary analysis of the BIG 1-98 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1335–1343. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soria J-C, DeBraud F, Bahleda R, et al. Phase I/IIa study evaluating the safety, efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of lucitanib in advanced solid tumors. Ann Oncol 2014 ;25:2244–2251. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu390. [Erratum: Ann Oncol 26:445, 2015] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lopez SM, Agoulnik AI, Zhang M, et al. Nuclear receptor corepressor 1 expression and output declines with prostate cancer progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:3937–3949. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines version 4.2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate_blocks.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pritchard CC, Mateo J, Walsh MF, et al. Inherited DNA-repair gene mutations in men with metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:443–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Annala M, Struss WJ, Warner EW, et al. Treatment outcomes and tumor loss of heterozygosity in germline DNA repair-deficient prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2017;72:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brovkina OI, Shigapova L, Chudakova DA, et al. The ethnic-specific spectrum of germline nucleotide variants in DNA damage response and repair genes in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer patients of Tatar descent. Front Oncol. 2018;8:421. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel E V, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Popova T, Manié E, Boeva V, et al. Ovarian cancers harboring inactivating mutations in CDK12 display a distinct genomic instability pattern characterized by large tandem duplications. Cancer Res. 2016;76:1882–1891. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Viswanathan SR, Ha G, Hoff AM, et al. Structural alterations driving castration-resistant prostate cancer revealed by linked-read genome sequencing. Cell. 2018;174:433–447.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Abida W, Bryce AH, Vogelzang NJ, et al: Preliminary results from TRITON2: A phase II study of rucaparib in patients (pts) with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) associated with homologous recombination repair (HRR) gene alterations. Ann Oncol 29, 2018 (suppl; abstr 793PD) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clarke N, Wiechno P, Alekseev B, et al. Olaparib combined with abiraterone in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:975–986. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30365-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]