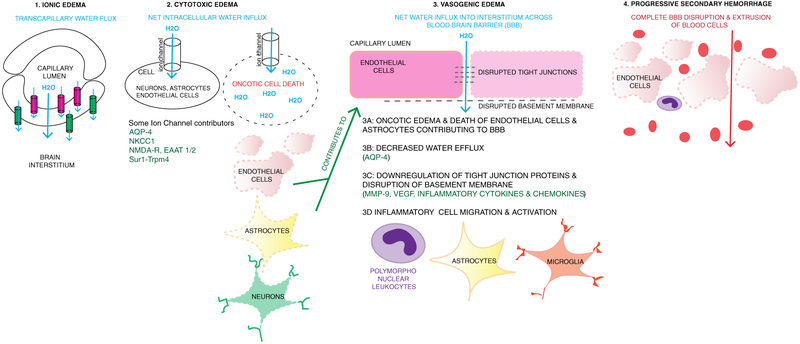

Fig. 4.

Continuum of ionic, cytotoxic and vasogenic edema, and progressive secondary hemorrhage. 1 Ionic edema involves transcapillary flux of ions and water across the capillary membrane. One hypothesis is that this is driven by osmotic forces. Ion channels expressed luminally (pink, such as NKCC1, Sur1-Trpm4) result in water movement into the endothelial cell, and then abluminal channels and transporters (green, e.g., Na+/K+ ATPase, Sur1-Trpm4) continue water movement across the cell into the interstitial space. The net movement of water (blue arrow) is from the capillary, across the endothelial cell, into the interstitial space. 2 Cytotoxic edema involves movement of water into cells including neurons, astrocytes, and endothelial cells. This occurs via various channels as listed including Sur1-Trpm4, NKCC1, EAAT1/2 and NMDA-R (glutamate channels), and AQP4. Intracellular influx of Na+ and water results in oncotic edema and cell death. When this occurs in endothelial cells and astrocytes containing podocytes that contribute to blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity, it contributes to disruption of the BBB and vasogenic edema. 3 Vasogenic edema involves water and proteinaceous fluid movement across a disrupted BBB. Multiple mechanisms contribute to vasogenic edema including oncotic edema of endothelial cells and astrocytes (3A, 2), decreased water efflux via AQP4 (3B), downregulation and disruption of tight junction proteins and the basement membrane (3C) and recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells such as peripheral leukocytes, astrocytes, and microglia (3D.) Disruption and downregulation of tight junctions and basement membrane proteins involves many pathways including MMP- 9, VEGF, and inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. These are also involved in recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells. 4 Progressive secondary hemorrhage when mechanisms of cellular and vasogenic edema result in complete disruption of the BBB and extravasation of blood cells and products into the interstitium