Abstract

Objective

Optimal targeted treatment in rheumatoid arthritis requires early identification of failure to respond. This post hoc analysis explored the relationship between early disease activity changes and the achievement of low disease activity (LDA) and remission targets with tofacitinib.

Methods

Data were from 2 randomized, double‐blind, phase III studies. In the ORAL Start trial, methotrexate (MTX)–naive patients received tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg twice daily, or MTX, for 24 months. In the placebo‐controlled ORAL Standard trial, MTX inadequate responder patients received tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg twice daily or adalimumab 40 mg every 2 weeks, with MTX, for 12 months. Probabilities of achieving LDA (using a Clinical Disease Activity Index [CDAI] score ≤10 or the 4‐component Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using the erythrocyte sedimentation rate [DAS28‐ESR] ≤3.2) at months 6 and 12 were calculated, given failure to achieve threshold improvement from baseline (change in CDAI ≥6 or DAS28‐ESR ≥1.2) at month 1 or 3.

Results

In ORAL Start, 7.2% and 5.4% of patients receiving tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily, respectively, failed to show improvement in the CDAI ≥6 at month 3; of those who failed, 3.8% and 28.6%, respectively, achieved month 6 CDAI‐defined LDA. In ORAL Standard, 18.8% and 17.5% of patients receiving tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily, respectively, failed to improve CDAI ≥6 at month 3; of those who failed, 0% and 2.9%, respectively, achieved month 6 CDAI‐defined LDA. Findings were similar when considering improvements at month 1 or DAS28‐ESR thresholds.

Conclusion

In patients with an inadequate response to MTX, lack of response to tofacitinib after 1 or 3 months predicted a low probability of achieving LDA at month 6. Lack of an early response may be considered when deciding whether to continue treatment with tofacitinib.

Introduction

Using the treat‐to‐target (or targeted treatment) approach in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) requires regular assessments of disease activity and adjustment of therapy associated with an inadequate response 1, 2. Thus, clinical guidelines recommend frequent follow‐up for patients with active disease to closely monitor disease activity and adjust treatment accordingly 3, 4. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) guidelines specify follow‐up every 1−3 months, with more frequent monitoring for patients with high disease activity; in addition, they suggest that if no improvement is seen within 3 months or if the treatment target is not reached within 6 months, treatment should be changed 4. To optimize this therapeutic strategy, an understanding of the relationship between short‐ and longer‐term responses is needed for each antirheumatic therapy.

Significance & Innovations.

We conducted a post hoc analysis of 2 randomized, double‐blind phase III studies of tofacitinib (ORAL Start and ORAL Standard), to explore the relationship between early disease activity changes and achievement of low disease activity (LDA) and remission targets.

Failure to achieve early improvements in disease activity (improvement from baseline using the Clinical Disease Activity Index score ≥6 or the 4‐component Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using the erythrocyte sedimentation rate ≥1.2) was predictive of low probabilities of achieving LDA and remission at months 6 and 12.

Lack of early response may be considered when deciding whether to continue treatment with tofacitinib.

While the therapeutic response to conventional synthetic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) is usually observed after 6 to 12 weeks of treatment 5, biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs) 6 and targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs) 7, 8 are often more rapidly effective. However, for all drug classes, the response to therapy is unpredictable 9, 10, and whether patients who fail to show an initial response to tsDMARDs might still respond later in the course of treatment is unclear.

There is evidence that early response to RA treatment predicts the probability of achieving the treatment target over time. Response at 4 weeks has been shown to be predictive of later response to csDMARDs 11 and to the JAK inhibitor baricitinib 12. Furthermore, the predictive value of failing to achieve an early response to a desired treatment target (negative predictive value [NPV]) may be greater than the predictive value of achievement of an early response (positive predictive value [PPV]). Both the Rheumatoid Arthritis Prevention of Structural Damage (RAPID 1) study 13 and the PREMIER study 14 showed that failure to achieve early improvements in disease activity with a combination of a bDMARD and methotrexate (MTX) was predictive of a low probability of achieving a longer‐term clinical response.

Tofacitinib is an oral JAK inhibitor for the treatment of RA. The efficacy and safety of tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily, administered as monotherapy or in combination with csDMARDs, mainly MTX, in patients with moderately to severely active RA, have been demonstrated in phase II 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 and phase III 7, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 studies of up to 24 months’ duration and in long‐term extension studies with up to 114 months of observation 25, 26, 27.

The aim of the current study was to understand the relationship between timing and magnitude of early changes in disease activity (at months 1 and 3) and the probability of achieving low disease activity (LDA) or remission at months 6 and 12 in 2 different patient populations treated with tofacitinib from phase III studies: patients with an inadequate response to MTX (MTX‐IR) receiving tofacitinib plus MTX in ORAL Standard, and MTX‐naive patients receiving tofacitinib monotherapy in ORAL Start.

Patients and Methods

Study design

This was a post hoc analysis of data from 2 randomized, double‐blind, phase III studies of tofacitinib. ORAL Start was a 24‐month study in MTX‐naive patients with RA. Patients were randomized 2:2:1 to receive tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily, tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily, or MTX at a starting dosage of 10 mg per week, with increments of 5 mg per week every 4 weeks to 20 mg per week by week 8 22.

ORAL Standard was a 12‐month study in MTX‐IR patients with RA. Patients were randomized 4:4:4:1:1 to receive tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily, tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily, adalimumab (ADA) 40 mg administered subcutaneously once every 2 weeks, placebo changing to tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily, or placebo changing to tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily, all with MTX 24. Patients in the placebo group advanced to tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg twice daily at month 3 if they were nonresponders (<20% reduction from baseline in both swollen and tender joint counts) or at month 6. Both studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and were approved by the institutional review boards and/or independent ethics committees at each investigational center. All patients provided written informed consent.

Patient inclusion

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for both studies have been reported previously 22, 24. Briefly, eligible patients were age ≥18 years, with a diagnosis of RA based on the American College of Rheumatology 1987 revised criteria 28, with active RA, defined as ≥6 tender/painful joints (68‐joint count) and ≥6 swollen joints (66‐joint count), and with either an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) >28 mm/hour or a C‐reactive protein (CRP) level >7 mg/liter.

Assessments

The Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI), as the primary analysis, and the 4‐component Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using the ESR (DAS28‐ESR) were assessed at baseline (prior to the first study dose), and at months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 (or at the end‐of‐study visit). LDA and remission criteria, respectively, were defined as CDAI score of ≤10 and ≤2.8 and as DAS28‐ESR of ≤3.2 and <2.6 29. The proportion of patients who failed to achieve a number of different thresholds of improvement in disease activity was assessed. Improvement thresholds were a decrease from baseline in CDAI of ≥3, ≥6, ≥9, and ≥12, and a decrease from baseline in DAS28‐ESR of ≥0.3, ≥0.6, ≥0.9, ≥1.2, ≥1.5, and ≥1.8 12. An improvement of ≥6 in CDAI after 4 weeks of treatment with baricitinib was found to be the minimum level predictive of a response at later time points 12, and an improvement of ≥1.2 in DAS28‐ESR and a baseline value of >5.1 are deemed a moderate response in patients with RA 30. These values were therefore considered as the key thresholds for improvement at months 1 and 3.

Statistical analysis

Data from the full analysis set, comprising all randomized patients who received ≥1 dose of study drug and had ≥1 post‐baseline value, were included. Both studies were analyzed separately due to differences in study design and patient populations. One‐year data were used, and nonresponder imputation was applied for missing values of the binary end points for all patients post‐baseline.

The probability that a patient achieved CDAI‐ or DAS28‐ESR–defined LDA or remission at month 6 or month 12 was calculated for each tofacitinib treatment group, given the failure to achieve improvement from baseline in disease activity at month 1 or month 3. For each patient, improvements from baseline were assessed across the prespecified range of thresholds, and the probability of achieving LDA and remission was estimated. Patients were categorized by whether they had achieved or failed to achieve improvement from baseline at the month 1 or month 3 visit. The number of patients who achieved LDA or remission at month 6 or month 12 was calculated, and the probability of achieving LDA or remission was estimated as a relative frequency. PPV (defined as the probability that patients who achieve LDA [CDAI ≤10 or DAS28‐ESR ≤2.3] or remission [CDAI ≤2.8 or DAS28‐ESR <2.6] at month 1 or month 3 will achieve LDA or remission at month 6 or month 12) and NPV (defined as the probability that patients who do not achieve LDA or remission at month 1 or month 3 will not achieve LDA or remission at month 6 or month 12) were calculated for the probabilities associated with each outcome.

Because this analysis is focused on the response to tofacitinib, data for the relationship between early changes in disease activity and the probability of achieving LDA or remission at month 6 and month 12 in patients randomized to receive MTX in ORAL Start or ADA in ORAL Standard are shown in Supplementary Appendix A and Supplementary Tables 1–7, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract. Also, because nonresponders receiving placebo in ORAL Standard moved to active treatment at month 3, patients randomized to receive placebo in this study were excluded from the analysis. Data on achievement of remission in both studies are fully reported in Supplementary Appendix A and Supplementary Tables 1–7, available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract.

Results

Patients

Overall, 948 patients from ORAL Start (tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily [n = 370], tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily [n = 394], MTX [n = 184]) and 717 patients from ORAL Standard (tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily [n = 204], tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily [n = 201], ADA [n = 204], placebo changing to tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily [n = 56], placebo changing to tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily [n = 52]) were randomized to study treatment. Patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics within each study were generally similar across treatment groups (see Supplementary Table 1, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract). Patients in ORAL Start were younger than those in ORAL Standard (mean ages 48.8–50.3 versus 52.5–53.8 years), with a shorter duration of RA (mean 2.7–3.4 versus 7.4–8.1 years), and a higher mean CRP level at baseline (20.2–26.1 versus 14.6–17.4 mg/liter).

Proportion of patients achieving LDA and remission

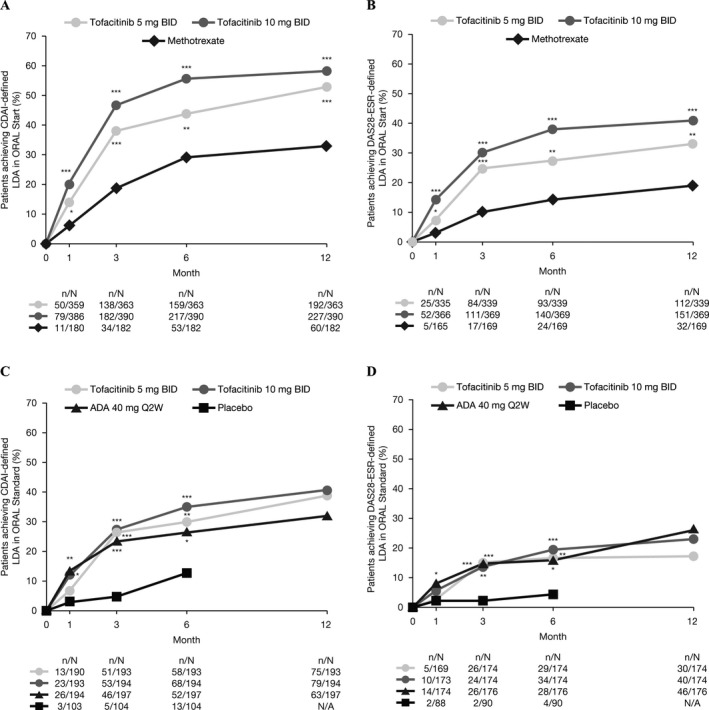

In both studies, a significantly greater proportion of patients achieved CDAI‐ and DAS28‐ESR–defined LDA with tofacitinib compared with MTX (ORAL Start) or placebo (ORAL Standard) at month 6 (Figure 1). In addition, a significantly greater proportion of patients achieved CDAI‐defined remission (tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily) and DAS28‐ESR–defined remission (both tofacitinib doses) versus MTX or placebo at month 6 (see Supplementary Figure 1, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract). In ORAL Standard, the proportions of patients achieving CDAI‐ and DAS28‐ESR–defined LDA and remission at month 6 were numerically similar for those patients receiving tofacitinib and those receiving ADA (Figures 1C and D and Supplementary Figures 1C and D, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract).

Figure 1.

Proportions of patients achieving (A) Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI)–defined low disease activity (LDA) in ORAL Start, (B) 4‐component Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28‐ESR)–defined LDA in ORAL Start, (C) CDAI‐defined LDA in ORAL Standard, and (D) DAS28‐ESR–defined LDA in ORAL Standard (full analysis set, nonresponder imputation). Low disease activity was defined as CDAI ≤10 or DAS28‐ESR ≤3.2. Because nonresponders receiving placebo in ORAL Standard moved to active treatment at month 3, patients randomized to receive placebo in this study were also excluded from the analysis. BID = twice a day; ADA = adalimumab; Q2W = every 2 weeks; N/A = not applicable; * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.001; *** = P < 0.0001.

Relationship between early changes in disease activity and rates of LDA at months 6 and 12 in ORAL Start (MTX‐naive)

At month 3, 7.2% of patients (26 of 359) receiving tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and 5.4% of patients (21 of 387) receiving tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily failed to achieve CDAI‐defined improvement from baseline ≥6. Of these patients, 3.8–11.5% with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and 19.0–28.6% with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily went on to achieve CDAI‐defined LDA at months 6 and 12 (Table 1 and Supplementary Figures 2A and B, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract). The NPV for CDAI‐defined LDA at month 6 associated with failure to achieve CDAI improvement at month 3 was 96% for tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and 71% for 10 mg twice daily, and was >80% at month 12 (Table 1 and Supplementary Figures 2A and B, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract). Among patients receiving MTX, 16.1% of those who failed to achieve CDAI improvement from baseline ≥6 at month 3 achieved CDAI‐defined LDA at month 6, with an associated NPV of 84% (see Supplementary Table 2, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract).

Table 1.

Probabilities of achieving low disease activity (LDA) at month 6 or month 12 given failure to achieve improvement in Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI)–defined disease activity at month 1 or month 3 with tofacitinib in ORAL Start (full analysis set, nonresponder imputation)*

| Achievement of LDA given failure to improve CDAI ≥6 | Probabilities of achieving LDA (CDAI ≤10) | NPV, % | PPV, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tofacitinib 5 mg BID | Tofacitinib 10 mg BID | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID | Tofacitinib 10 mg BID | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID | Tofacitinib 10 mg BID | |

| Month 6 | ||||||

| Failure to improve at month 1 | 15/84 (17.9) | 22/65 (33.8) | 82.1 | 66.2 | 51.1 | 60.1 |

| Failure to improve at month 3 | 1/26 (3.8) | 6/21 (28.6) | 96.2 | 71.4 | 46.3 | 57.1 |

| Month 12 | ||||||

| Failure to improve at month 1 | 30/84 (35.7) | 31/65 (47.7) | 64.3 | 52.3 | 58.4 | 60.8 |

| Failure to improve at month 3 | 3/26 (11.5) | 4/21 (19.0) | 88.5 | 81.0 | 56.2 | 60.7 |

Unless indicated otherwise, values are the number of patients who failed to meet the improvement threshold/the number who also achieved LDA (defined as CDAI ≤10) (%). BID = twice daily; NPV = negative predictive value (defined as the probability that patients who do not achieve LDA at month 1 or month 3 will not achieve LDA at month 6 or month 12); PPV = positive predictive value (defined as the probability that patients who achieve LDA at month 1 or month 3 will achieve LDA at month 6 or month 12).

Similarly, at month 3, 21.8% of patients (74 of 339) receiving tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and 14.4% of patients (53 of 369) receiving tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily failed to achieve DAS28‐ESR–defined improvement from baseline ≥1.2. Of these patients, 6.8–14.9% with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and 11.3–22.6% with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily achieved DAS28‐ESR–defined LDA at months 6 and 12 (Table 2 and Supplementary Figures 2C and D, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract). The NPV for DAS28‐ESR–defined LDA at month 6 associated with failure to achieve DAS28‐ESR–defined improvement at month 3 was 93% and 89% for tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily, respectively, and 85% and 77% at month 12 for tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily, respectively (Table 2 and Supplementary Figures 2C and D, available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract). For patients receiving MTX, 6.2% of those who failed to achieve DAS28‐ESR–defined improvement from baseline ≥1.2 at month 3 achieved DAS28‐ESR–defined LDA at month 6, with an associated NPV of 94% (see Supplementary Table 2, available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract). The relationship between early changes in disease activity using different thresholds and rates of LDA at months 6 and 12 are shown in Supplementary Figure 2, available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract.

Table 2.

Probabilities of achieving low disease activity (LDA) at month 6 or month 12 given failure to achieve improvement in DAS28‐ESR–defined disease activity at month 1 or month 3 with tofacitinib in ORAL Start (full analysis set, nonresponder imputation)*

| Achievement of LDA given failure to improve DAS28‐ESR ≥1.2 | Probabilities of achieving LDA (DAS28‐ESR ≤3.2) | NPV, % | PPV, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tofacitinib 5 mg BID | Tofacitinib 10 mg BID | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID | Tofacitinib 10 mg BID | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID | Tofacitinib 10 mg BID | |

| Month 6 | ||||||

| Failure to improve at month 1 | 22/150 (14.7) | 23/118 (19.5) | 85.3 | 80.5 | 37.8 | 46.8 |

| Failure to improve at month 3 | 5/74 (6.8) | 6/53 (11.3) | 93.2 | 88.7 | 33.2 | 42.4 |

| Month 12 | ||||||

| Failure to improve at month 1 | 37/150 (24.7) | 31/118 (26.3) | 75.3 | 73.7 | 40.0 | 47.6 |

| Failure to improve at month 3 | 11/74 (14.9) | 12/53 (22.6) | 85.1 | 77.4 | 38.1 | 44.0 |

Unless indicated otherwise, values are the number of patients who failed to meet the improvement threshold/the number who also achieved LDA (defined as DAS28‐ESR ≤3.2) (%). DAS28‐ESR = 4‐component Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using the erythrocyte sedimentation rate; BID = twice daily; NPV = negative predictive value (defined as the probability that patients who do not achieve LDA at month 1 or month 3 will not achieve LDA at month 6 or month 12); PPV = positive predictive value (defined as the probability that patients who achieve LDA at month 1 or month 3 will achieve LDA at month 6 or month 12).

ORAL Standard (MTX‐IR)

At month 3, 18.8% of patients (36 of 191) receiving tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and 17.5% of patients (34 of 194) receiving tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily failed to achieve CDAI improvement from baseline ≥6. Of these patients, 0–2.8% treated with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and 2.9–8.8% treated with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily achieved CDAI‐defined LDA at months 6 and 12 (Table 3 and Supplementary Figures 3A and B, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract). The NPV for CDAI‐defined LDA at month 6 or month 12 associated with failure to achieve CDAI improvement from baseline ≥6 at month 3 was >90% for tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily (Table 3 and Supplementary Figures 3A and B, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract). Among patients receiving ADA, 6.1% of those who failed to achieve CDAI‐defined improvement from baseline ≥6 at month 3 achieved CDAI‐defined LDA at month 6, with an associated NPV of 94% (see Supplementary Table 3, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract).

Table 3.

Probabilities of achieving low disease activity (LDA) at month 6 or month 12 given failure to achieve improvement in Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI)–defined disease activity at month 1 or month 3 with tofacitinib in ORAL Standard (full analysis set, nonresponder imputation)*

| Achievement of LDA given failure to improve CDAI ≥6 | Probabilities of achieving LDA (CDAI ≤10) | NPV, % | PPV, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tofacitinib 5 mg BID | Tofacitinib 10 mg BID | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID | Tofacitinib 10 mg BID | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID | Tofacitinib 10 mg BID | |

| Month 6 | ||||||

| Failure to improve at month 1 | 5/51 (9.8) | 9/48 (18.8) | 90.2 | 81.3 | 38.4 | 40.0 |

| Failure to improve at month 3 | 0/36 (0) | 1/34 (2.9) | 100.0 | 97.1 | 37.4 | 41.9 |

| Month 12 | ||||||

| Failure to improve at month 1 | 9/51 (17.6) | 10/48 (20.8) | 82.4 | 79.2 | 47.1 | 47.6 |

| Failure to improve at month 3 | 1/36 (2.8) | 3/34 (8.8) | 97.2 | 91.2 | 47.7 | 47.5 |

Unless indicated otherwise, values are the number of patients who failed to meet the improvement threshold/the number who also achieved LDA (defined as CDAI ≤10) (%). BID = twice daily; NPV = negative predictive value (defined as the probability that patients who do not achieve LDA at month 1 or month 3 will not achieve LDA at month 6 or month 12); PPV = positive predictive value (defined as the probability that patients who achieve LDA at month 1 or month 3 will achieve LDA at month 6 or month 12).

At month 3, 31.6% of patients (55 of 174) receiving tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and 36.2% of patients (63 of 174) receiving tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily failed to achieve DAS28‐ESR improvement from baseline ≥1.2. Of these patients, none with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and 3.2–7.9% with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily achieved DAS28‐ESR–defined LDA at months 6 and 12 (Table 4 and Supplementary Figures 3C and D, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract). The NPV for DAS28‐ESR–defined LDA at month 6 or month 12 associated with failure to achieve DAS28‐ESR–defined improvement from baseline ≥1.2 at month 3 was >90% for tofacitinib 5 mg and 10 mg twice daily (Table 4 and Supplementary Figures 3C and D, available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract). Among patients receiving ADA, 5.5% of those who failed to achieve DAS28‐ESR–defined improvement from baseline ≥1.2 at month 3 achieved DAS28‐ESR–defined LDA at month 6, with an associated NPV of 95% (see Supplementary Table 3, available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract).

Table 4.

Probabilities of achieving low disease activity (LDA) at month 6 or month 12 given failure to achieve improvement in DAS28‐ESR–defined disease activity at month 1 or month 3 with tofacitinib in ORAL Standard (full analysis set, nonresponder imputation)*

| Achievement of LDA given failure to improve DAS28‐ESR ≥1.2 | Probabilities of achieving LDA (DAS28‐ESR ≤3.2) | NPV, % | PPV, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tofacitinib 5 mg BID | Tofacitinib 10 mg BID | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID | Tofacitinib 10 mg BID | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID | Tofacitinib 10 mg BID | |

| Month 6 | ||||||

| Failure to improve at month 1 | 7/85 (8.2) | 11/87 (12.6) | 91.8 | 87.4 | 26.2 | 25.6 |

| Failure to improve at month 3 | 0/55 (0) | 2/63 (3.2) | 100.0 | 96.8 | 24.4 | 28.8 |

| Month 12 | ||||||

| Failure to improve at month 1 | 10/85 (11.8) | 9/87 (10.3) | 88.2 | 89.7 | 22.6 | 34.9 |

| Failure to improve at month 3 | 0/55 (0) | 5/63 (7.9) | 100.0 | 92.1 | 25.2 | 31.5 |

Unless indicated otherwise, values are the number of patients who failed to meet the improvement threshold/the number who also achieved LDA (defined as DAS28‐ESR ≤3.2) (%). DAS28‐ESR = 4‐component Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using the erythrocyte sedimentation rate; BID = twice daily; NPV = negative predictive value (defined as the probability that patients who do not achieve LDA at month 1 or month 3 will not achieve LDA at month 6 or month 12); PPV = positive predictive value (defined as the probability that patients who achieve LDA at month 1 or month 3 will achieve LDA at month 6 or month 12).

Relationship between early changes in disease activity and rates of remission at months 6 and 12

In both ORAL Start and ORAL Standard and across treatment groups (tofacitinib, MTX, and ADA), failure to achieve improvement thresholds (decrease from baseline of CDAI ≥6 and DAS28‐ESR ≥1.2) at months 1 and 3 was predictive of low probabilities of remission at months 6 and 12 (see Supplementary Tables 4–7, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract).

Relationship between timing and magnitude of early changes in disease activity and rates of LDA

In both ORAL Start and ORAL Standard, failure to achieve improvement thresholds at month 1, whether defined by CDAI or DAS28‐ESR, was less strongly predictive of achievement of LDA at month 6 or month 12 than failure to achieve improvement thresholds at month 3 (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4) for patients receiving tofacitinib. Indeed, the NPVs for LDA at month 6 associated with failure to achieve threshold improvement from baseline at month 1 were lower than those associated with failure to achieve threshold improvement from baseline at month 3 for all treatments in both studies (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4). A similar pattern in NPVs was observed for patients receiving MTX (see Supplementary Table 2, available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract) and ADA (see Supplementary Table 3, at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract).

In both ORAL Start and ORAL Standard, for both tofacitinib groups, failure to achieve greater improvement thresholds in disease activity at month 3 was generally associated with an increasing proportion of patients achieving LDA at months 6 and 12, compared with failure to achieve lower improvement thresholds (see Supplementary Figures 2 and 3, available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.23585/abstract). Data are not reported for patients receiving MTX or ADA.

Discussion

This was a post hoc analysis of data from 2 phase III randomized controlled trials (RCTs), undertaken to explore the relationship between early changes in disease activity and the probability of achieving LDA or remission at month 6 and month 12 in MTX‐IR (ORAL Standard) or MTX‐naive (ORAL Start) patients with RA who were treated with tofacitinib, with the aim of improving patient management. Greater proportions of patients receiving tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily who were MTX‐naive achieved LDA and remission compared with patients who were MTX‐IR.

Across both studies, failure to achieve early improvements in disease activity (improvement from baseline of CDAI ≥6 or DAS28‐ESR ≥1.2) was predictive of low probabilities of achieving LDA and remission at months 6 and 12 with tofacitinib, MTX, and ADA. In this analysis, disease activity as assessed by the CDAI was considered the primary analysis; however, findings using DAS28‐ESR thresholds and DAS28‐ESR–defined LDA were supportive. Findings were similar when considering early improvements in disease activity at month 3 or month 1, and when taking achievement of LDA at month 6 or month 12 as targets.

In this analysis, higher values were reported for NPV than PPV for the achievement of longer‐term LDA based on early changes in disease activity. The consistently higher values for NPV versus PPV indicate that, although improvement at early time points is not necessarily predictive of achievement of treatment targets, failure to see early improvements predicts that such targets will not be reached. The NPV for LDA at month 6 associated with a failure to achieve CDAI improvement ≥6 and DAS28‐ESR improvement ≥1.2 at month 3 generally exceeded 90% for tofacitinib in ORAL Standard and 70% in ORAL Start (corresponding data for ADA in ORAL Standard exceeded 90%, and those for MTX in ORAL Start exceeded 80%), providing robust evidence that failure to achieve these improvement thresholds at month 3 was strongly predictive of failure to achieve LDA at month 6.

These findings are consistent with those from other RA studies reporting early treatment response as predictive of longer‐term outcomes. In prior analyses of ORAL Standard, few patients who failed to achieve improvement in disease activity (decrease in DAS28‐ESR ≥0.6) after 1 month with tofacitinib and background MTX then achieved LDA at 12 months 31. An analysis of an observational cohort of patients with RA (<12 months’ symptom duration) receiving csDMARDs reported that DAS28‐ESR scores at 4 weeks predicted scores at 28 and 52 weeks 11. Analysis of 2 phase III RCTs of baricitinib demonstrated that failure to achieve a decrease in DAS28‐ESR ≥0.6 or CDAI ≥6 after 4 weeks of treatment was associated with low rates of LDA or remission at 12 or 24 weeks 12. High NPVs were also reported in the RAPID 1 trial, in which failure to achieve improvement in DAS28‐ESR within the first 12 weeks of treatment with certolizumab pegol and MTX was predictive of a low probability of achieving LDA at 1 year, with the accuracy of the prediction strongly dependent on the degree and timing of the lack of the response 13. Similarly, the PREMIER study reported that patients receiving MTX who did not show a clinical response at 3 months demonstrated worse long‐term clinical, functional, and radiographic outcomes 14. This information supports current recommendations for targeted treatment, specifically EULAR guidelines, suggesting that if no improvement is seen within 3 months, or if the treatment target is not reached within 6 months, treatment should be changed 4.

A number of limitations in this analysis should be considered. This was a post hoc analysis, and the studies were not designed to consider the relationship between changes in disease activity at months 1 and 3 and the achievement of LDA or remission at month 6 and 12. Joint structure preservation was not considered in this analysis; however, disease activity measures may not always correlate with radiographic outcomes 32, and further research into this correlation is ongoing. Due to differing study designs and the inclusion of different patient populations, data from the studies could not be pooled for analysis. Patient numbers were relatively low in some groups, resulting in the need to interpret findings with caution. Finally, this analysis did not explore the association of baseline characteristics with outcomes; this question will be addressed in a separate analysis exploring predicted treatment outcome based on several baseline clinical and sociodemographic characteristics.

In conclusion, this analysis of data from ORAL Start and ORAL Standard shows that failure to achieve improvements in disease activity at months 1 and 3 is predictive of a low probability of achieving LDA and remission at months 6 and 12. Given that lack of early improvement may be predictive of a low probability of achieving stringent disease activity targets, decisions on the continuation of tofacitinib treatment in patients with moderately to severely active RA may benefit from consideration of early assessment of response.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be submitted for publication. Dr. Keystone had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design.

van Vollenhoven, Lee, Fallon, Zwillich, Wilkinson, Chapman, DeMasi, Keystone.

Acquisition of data.

van Vollenhoven, Lee, Wilkinson, Chapman.

Analysis and interpretation of data.

van Vollenhoven, Lee, Fallon, Zwillich, Wilkinson, Chapman, DeMasi, Keystone.

Role of the Study Sponsor

The studies included in this analysis were funded by Pfizer Inc. This analysis was conceived by the Pfizer, Inc. authors in collaboration with the academic authors. All authors were involved in interpreting the data and in drafting, reviewing, and developing the manuscript. Medical writing support was funded by Pfizer, Inc. Publication of this article was not contingent upon approval by Pfizer, Inc.

Supporting information

Supplementary Figure 1

Supplementary Figure 2

Supplementary Figure 3

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients, investigators, and study teams involved in the ORAL Start and ORAL Standard studies. Medical writing support, under the guidance of the authors, was provided by Karen Irving, PhD, at CMC Connect, a division of Complete Medical Communications Ltd, Glasgow, UK, and by Carole Evans, PhD, on behalf of CMC Connect.

Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT01039688 and NCT00853385.

Supported by Pfizer, Inc.

Dr. van Vollenhoven has received grant/research support from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Inc, Roche, and UCB, and has received consulting fees from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Biotest, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Celgene, Crescendo, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Inc, Roche, UCB, and Vertex (less than $10,000 each). Dr. Lee has received consulting fees from Pfizer Inc (less than $10,000) and has received research support from Green Cross Co. Dr. Keystone has received grant/research support and consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, and Lilly (more than $10,000 each), and has received consulting fees from Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Pfizer Inc, and Roche (less than $10,000 each). Dr. Wilkinson, Dr. Fallon, Mr. Chapman, Dr. Zwillich, and Dr. DeMasi are employees and shareholders of Pfizer, Inc.

References

- 1. Schoels M, Knevel R, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, Breedveld FC, Boumpas DT, et al. Evidence for treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: results of a systematic literature search. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:638–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stoffer MA, Schoels MM, Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Breedveld FC, Burmester G, et al. Evidence for treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: results of a systematic literature search update. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, Akl EA, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, Burmester G, Chatzidionysiou K, Dougados M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:960–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. O'Connor A, Thorne C, Kang H, Tin D, Pope JE. The rapid kinetics of optimal treatment with subcutaneous methotrexate in early inflammatory arthritis: an observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016;17:364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Curtis JR, Singh JA. Use of biologics in rheumatoid arthritis: current and emerging paradigms of care. Clin Ther 2011;33:679–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fleischmann R, Kremer J, Cush J, Schulze‐Koops H, Connell CA, Bradley JD, et al. Placebo‐controlled trial of tofacitinib monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2012;367:495–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuriya B, Cohen MD, Keystone E. Baricitinib in rheumatoid arthritis: evidence‐to‐date and clinical potential. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2017;9:37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shao W, Yuan Y, Li Y. Association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and methotrexate treatment outcome in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 2017;21:275–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bastida C, Ruiz V, Pascal M, Yague J, Sanmarti R, Soy D. Is there potential for therapeutic drug monitoring of biologic agents in rheumatoid arthritis? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2017;83:962–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. White D, Pahau H, Duggan E, Paul S, Thomas R. Trajectory of intensive treat‐to‐target disease modifying drug regimen in an observational study of an early rheumatoid arthritis cohort. BMJ Open 2013;3:pii.e003083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kremer J, Dougados M, Genovese MC, Emery P, Yang L, de Bono S, et al. Response to baricitinib at 4 weeks predicts response at 12 and 24 weeks in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from two phase 3 studies [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67 Suppl 10. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van der Heijde D, Keystone EC, Curtis JR, Landewe RB, Schiff MH, Khanna D, et al. Timing and magnitude of initial change in disease activity score 28 predicts the likelihood of achieving low disease activity at 1 year in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with certolizumab pegol: a post‐hoc analysis of the RAPID 1 trial. J Rheumatol 2012;39:1326–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Keystone EC, Haraoui B, Guerette B, Mozaffarian N, Liu S, Kavanaugh A. Clinical, functional, and radiographic implications of time to treatment response in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: a posthoc analysis of the PREMIER study. J Rheumatol 2014;41:235–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fleischmann R, Cutolo M, Genovese MC, Lee EB, Kanik KS, Sadis S, et al. Phase IIb dose‐ranging study of the oral JAK inhibitor tofacitinib (CP‐690,550) or adalimumab monotherapy versus placebo in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:617–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kremer JM, Cohen S, Wilkinson BE, Connell CA, French JL, Gomez‐Reino J, et al. A phase IIb dose‐ranging study of the oral JAK inhibitor tofacitinib (CP‐690,550) versus placebo in combination with background methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate alone. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:970–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kremer JM, Bloom BJ, Breedveld FC, Coombs JH, Fletcher MP, Gruben D, et al. The safety and efficacy of a JAK inhibitor in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results of a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled phase IIa trial of three dosage levels of CP‐690,550 versus placebo. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:1895–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tanaka Y, Takeuchi T, Yamanaka H, Nakamura H, Toyoizumi S, Zwillich S. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib as monotherapy in Japanese patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: a 12‐week, randomized, phase 2 study. Mod Rheumatol 2015;25:514–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tanaka Y, Suzuki M, Nakamura H, Toyoizumi S, Zwillich SH, and the Tofacitinib Study Investigators . Phase II study of tofacitinib (CP‐690,550) combined with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:1150–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burmester GR, Blanco R, Charles‐Schoeman C, Wollenhaupt J, Zerbini C, Benda B, et al. Tofacitinib (CP‐690,550) in combination with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381:451–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kremer J, Li ZG, Hall S, Fleischmann R, Genovese M, Martin‐Mola E, et al. Tofacitinib in combination with nonbiologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:253–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee EB, Fleischmann R, Hall S, Wilkinson B, Bradley J, Gruben D, et al. Tofacitinib versus methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2377–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Van der Heijde D, Tanaka Y, Fleischmann R, Keystone E, Kremer J, Zerbini C, et al. Tofacitinib (CP‐690,550) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate: twelve‐month data from a twenty‐four‐month phase III randomized radiographic study. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:559–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van Vollenhoven RF, Fleischmann R, Cohen S, Lee EB, García Meijide JA, Wagner S, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2012;367:508–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wollenhaupt J, Silverfield J, Lee EB, Curtis JR, Wood SP, Soma K, et al. Safety and efficacy of tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in open‐label, longterm extension studies. J Rheumatol 2014;41:837–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yamanaka H, Tanaka Y, Takeuchi T, Sugiyama N, Yuasa H, Toyoizumi S, et al. Tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, as monotherapy or with background methotrexate, in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis: an open‐label, long‐term extension study. Arthritis Res Ther 2016;18:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wollenhaupt J, Silverfield J, Lee EB, Terry K, Kwok K, Strengholt S, et al. Tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: safety and efficacy in open‐label, long‐term extension studies over 9 years [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69 Suppl 10. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988;31:315–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Anderson J, Caplan L, Yazdany J, Robbins ML, Neogi T, Michaud K, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis disease activity measures: American College of Rheumatology recommendations for use in clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:640–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Van Riel PL, Renskers L. The Disease Activity Score (DAS) and the Disease Activity Score using 28 joint counts (DAS28) in the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016;34:S40–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Van Vollenhoven RF, Krishnaswami S, Benda B, Gruben D, Wilkinson B, Mebus C, et al. Tofacitinib and adalimumab achieve similar rates of low disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: lack of improvement in disease activity score by 3 months predicts low likelihood of low disease activity at 1 year [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:S556. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Strand V, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Lee EB, Wilkinson B, Zwillich SH, et al. Remission at 3 or 6 months and radiographic non‐progression at 12 months in methotrexate‐naïve rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tofacitinib or methotrexate: a post‐hoc analysis of the ORAL Start Trial [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:S842–3. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1

Supplementary Figure 2

Supplementary Figure 3

Supplementary Material