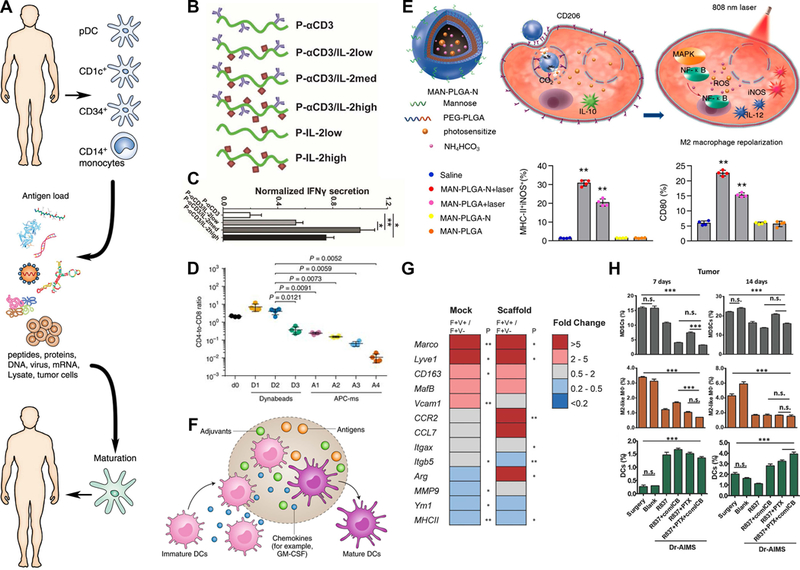

Figure 3. Targeting and mimicry of APCs to promote immunity against cancer.

A) Conventional paradigm for DC-based vaccines where innate immune populations are removed from a patient, conditioned ex vivo with factors like tumor lysate to promote maturation, the reintroduced to provide signals to the patient’s adaptive immune cells.53. B-C) Artificial APCs that control the presentation of cytokines to T cells and D) incorporate T cell costimulatory factors to generate cytotoxic T cells.55,56 This incorporation of T cell costimulatory factors in artificial APC scaffolds (APC-ms) at a range of loadings (A1-A4) was benchmarked against T cell activating Dynabeads administered at a range of doses (D1-D3). E) Combinatorial approach to switch TAMs toward immunogenic phenotype by including mannose binding sites on PLGA NPs that were loaded with drug and photosensitizers to control macrophage inflammation at specific sites.63 F) Implanted biomaterials scaffolds are able to mature DC phenotypes in situ through recruitment and exposure to antigens, adjuvants, and chemokines.52. G) Presence of an implanted scaffold alone impacts the phenotype of TAMs, as demonstrated through gene expression analysis of TAM populations following a mock surgery (left column) or scaffold implantation (right column).68 H) Implants for release of different drug combinations at tumor resection site were compared at Days 7 and 14 for the impact on MDSCs, TAMs (M2-like macrophages), and DCs.70 Panels adapted with permission from the indicated references.