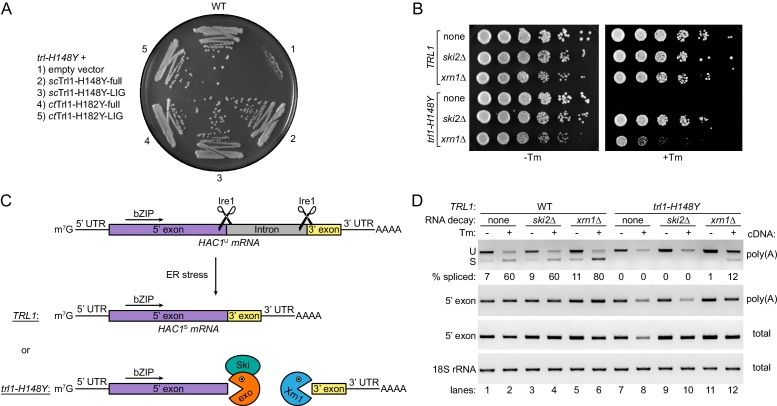

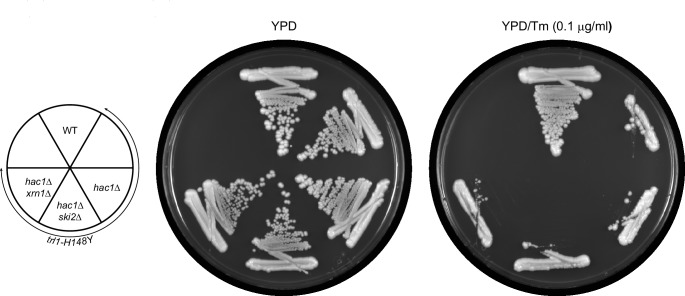

Figure 5. HAC1 mRNA splicing competes with general RNA decay pathways.

(A) Overexpression of various Trl1 constructs rescued the growth phenotype of trl1-H148Y. The constructs from S. cerevisiae harbored the H148Y mutation of the trl1-H148Y allele, whereas those from C. thermophilum harbored the equivalent H182Y mutation. Both the full-length proteins and the isolated ligase domains restored growth of the UPR mutant strain when streaked on tunicamycin-containing YPD plates. (B) Serial five-fold dilutions of wild-type and trl1-H148Y cells with wild-type or abrogated (ski2Δ or xrn1Δ) RNA decay pathways were spotted on YPD plates without (-Tm) or with (+Tm) 0.1 μg/ml tunicamycin and incubated at 30°C for 2 days. (C) Model of HAC1 mRNA splicing and the impact of RNA decay pathways on degradation of cleaved HAC1 exons. Ire1 cleaves unspliced HAC1 mRNA (HAC1U) at the non-conventional splice sites upon ER stress. In wild-type yeast cells (TRL1), exon-exon ligation by Trl1 is the predominant reaction yielding spliced HAC1 mRNA (HAC1S). In the context of a kinetically compromised tRNA ligase (trl1-H148Y), the cleaved HAC1 exons are degraded by exonucleolytic RNA decay pathways. The capped (m7G) 5’ exon is susceptible to degradation in 3’-to-5’ direction by the RNA exosome (exo)/Ski complex (Ski); the 3’ exon is degraded from its 5’ end by Xrn1. (D) RT-PCR analysis of HAC1 mRNA splicing in the same strains as in B without and with tunicamycin (Tm). The top panel shows priming outside the exon-intron junctions to distinguish unspliced (U) from spliced (S) HAC1 mRNA. The relative amount of HAC1S (in %) is indicated below each lane. Both middle panels show the results for priming of the 5’ exon. 18S rRNA was used as a control (bottom panel). The method of cDNA production is indicated on the right of each panel.