Abstract

Introduction

Surgical-site infection (SSI) is the second most frequent cause of healthcare-associated infection worldwide and is associated with increased morbidity, mortality and healthcare costs. Cardiac surgery is clean surgery with low incidence of SSI, ranging from 2% to 5%, but with potentially severe consequences.

Perioperative skin antisepsis with an alcohol-based antiseptic solution is recommended to prevent SSI, but the superiority of chlorhexidine (CHG)–alcohol over povidone iodine (PVI)–alcohol, the two most common alcohol-based antiseptic solutions used worldwide, is controversial. We aim to evaluate whether 2% CHG–70% isopropanol is more effective than 5% PVI–69% ethanol in reducing the incidence of reoperation after cardiac surgery.

Methods and analysis

The CLEAN 2 study is a multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled clinical trial of 4100 patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Patients will be randomised in 1:1 ratio to receive either 2% CHG–70% isopropanol or 5% PVI–69% ethanol for perioperative skin preparation. The primary endpoint is the proportion of patients undergoing any re-sternotomy between day 0 and day 90 after initial surgery and/or any reoperation on saphenous vein/radial artery surgical site between day 0 and day 30 after initial surgery. Data will be analysed on the intention-to-treat principle.

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol has been approved by an independent ethics committee and will be carried out according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The results of this study will be disseminated through presentation at scientific conferences and publication in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

EudraCT 2017-005169-33 and NCT03560193.

Keywords: surgical-site infection, skin antisepsis, cardiac surgery, chlorhexidine, povidone iodine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This randomised study is aimed at being the largest one performed comparing the efficacy of perioperative skin preparation with either alcohol-based chlorhexidine or alcohol-based povidone iodine in reducing severe postoperative complications.

The primary endpoint, the incidence of any reoperation at both surgical sites, is a predefined strong and unquestionable criterion, underscoring the need—and the risk of bias—to assess the reality of surgical-site infection (SSI).

Limitations due to the lack of masking related to the nature of the intervention will be reduced by assessment of all SSIs by an adjudication committee masked to the antiseptic group.

Introduction

Surgical-site infection (SSI) is the second most frequent cause of healthcare-associated infections with an incidence up to 19% depending on the type of surgery, and ranges from simple wound discharge to life-threatening condition.1–3 It is associated with increased hospital stay, prolonged antibiotic use and occasional need for reoperation, and is responsible for rising mortality and healthcare costs estimated at €10 billion per year in the USA.4

Cardiac surgery is considered as clean surgery. Incidence of SSI is lower than with other types of surgery, ranging from 2% to 5% depending on the definitions used, but its consequences may be greater in terms of both frequency and severity.5 6 Because pathogens involved in SSI after clean surgery come mostly from skin, perioperative skin antisepsis plays a major role in SSI prevention.

The most common antiseptic agents used for skin disinfection before surgery are aqueous or alcoholic formulations of chlorhexidine (CHG) or povidone iodine (PVI), both of which are available at various concentrations. Several studies have compared their respective efficacy and safety in reducing SSI. Nevertheless, results have been contradictory, probably due to different comparators (concentrations, combination with alcohol or water and so on), different SSI definitions and different lengths of follow-up.7–11 In 2010, a meta-analysis of seven randomised-controlled trials (including 3437 patients) compared CHG (at a concentration of 0.5%–4%) with PVI or other iodophors (at a concentration of 7%–10%) for preoperative skin antisepsis in clean and clean-contaminated surgery.12 The use of CHG was associated with fewer SSIs (adjusted RR 0.64; 95% CI 0.51 to 0.80) compared with iodine. Another meta-analysis of six randomised-controlled trials comparing CHG (at a concentration of 0.5%–4%) to PVI (at a concentration of 7.5%–10%) for preoperative skin antisepsis yielded similar findings (OR of 0.68 (0.50–0.94; p=0.019)).13 However, in most studies, CHG was combined with alcohol and PVI was not, which meant that two antiseptics were being compared with only one. A review conducted in 2012 was unable to draw any conclusion about which surgical site antiseptic more effectively reduces SSI.14 Recently, Tuuli and colleagues were the first to conduct a large trial comparing CHG and PVI in alcoholic formulations for skin disinfection before caesarean section.9 Interestingly, both antiseptic formulations used the same alcohol at the same concentration and both were applied similarly, using an applicator. Although this was the first study demonstrating a benefit of 2% CHG–70% isopropanol over 8.3% PVI–70% isopropanol, it was monocentre, and did not address all potential methodological limits. Especially, the choice of superficial or deep SSI as primary endpoint assessed by the surgeon (the diagnosis was made by the treating physician and verified through chart review by the principal investigator, who was unaware of the study-group assignments) may generate interpretation biases in an open study. Moreover, the one dual microbial source of pathogens of both skin and vaginal origins in SSI after caesarean delivery and immune modulation in pregnancy raises questions about whether the results of trials of preoperative skin antisepsis for caesarean delivery can be extrapolated to other surgical procedures.

Furthermore, the possible superiority of CHG over PVI was not confirmed in a second monocentre trial involving 1404 women requiring caesarean section.8 Lastly, in a third assessor-blinded, monocentre, randomised trial involving 802 patients scheduled for elective clean-contaminated colorectal surgery, the use of PVI–alcohol failed to meet the criterion for non-inferiority in SSI occurrence compared with CHG–alcohol.11 These contradictory results may explain the lack of universal use of CHG–alcohol for skin antisepsis in surgery despite the recommendations of the WHO.15

The prevalence and potential serious consequences of SSI in cardiac surgery, especially mediastinitis, support a large randomised controlled trial in this setting. We hypothesise that perioperative skin preparation with 2% CHG–70% isopropanol is more effective than 5% PVI–69% ethanol as a means of preventing any reoperation after cardiac surgery.

Methods and analysis

Trial design and setting

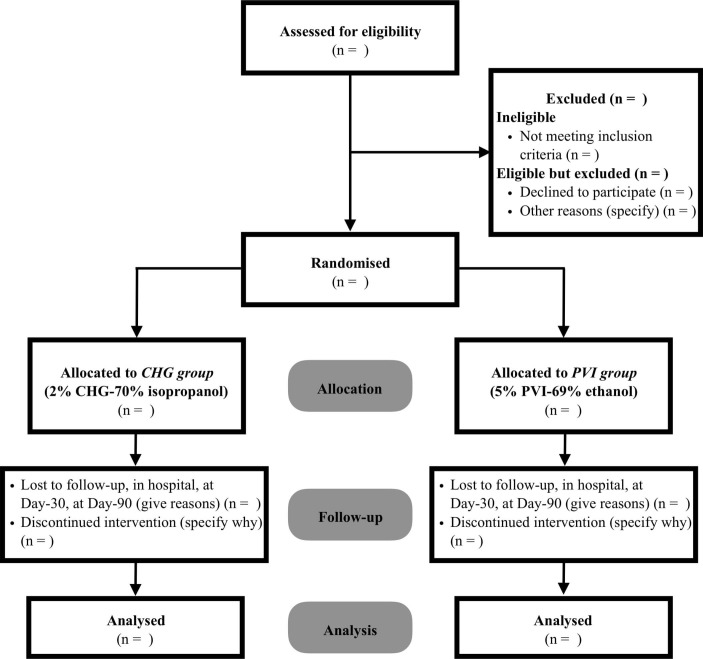

The CLEAN 2 trial is an investigator-initiated, publicly funded multicentre, randomised, controlled, open-label clinical trial with concealed allocation of patients scheduled to undergo cardiac surgery and to receive 1:1 either 2% CHG–70% isopropanol or 5% PVI–69% ethanol for perioperative skin preparation. Randomisation will be carried out through a secure web-based randomisation system and stratified by centre (figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram (CHG, chlorhexidine; PVI, povidone iodine).

The trial will take place at seven university and non-university French hospitals. All participating centres perform more than 500 cardiac surgical procedures per year.

Participant eligibility and consent

During surgery or preoperative anaesthesia consultation, all consecutive patients will be considered candidates for inclusion in the study if they meet all of the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria. Eligible patients will receive oral and written information and will be enrolled after having given written consent.

Inclusion criteria

Adult patients (age ≥18 years) admitted in one of the participating centres.

Scheduled to undergo surgery of the heart (valve, coronary or combined surgery) or of the aorta via median sternotomy.

Having signed informed consent form.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with known allergies to CHG, PVI, isopropanol or ethanol.

Surgery for heart transplantation.

Any signs of inflammation or sternal instability at the site of sternotomy or operation for infection (sternal wound infection (SWI) or endocarditis).

History of cardiac surgery within 3 months preceding enrolment.

Participation in another clinical trial aimed at reducing SSI.

Patients already enrolled in this study.

Pregnant or breastfeeding women and potentially childbearing women without effective contraception.

Patients not benefiting from a Social Security scheme or not benefiting from it through a third party.

Persons benefiting from enhanced protection, namely minors, persons deprived of their liberty by a judicial or administrative decision and adults under legal protection.

Assignment of interventions

A computer-generated block-randomisation sequence will be performed by a statistician not involved in either screening the patients or assessing outcomes. Randomisation will be carried out using a secure web-based randomisation system with stratification by centre. The randomisation will be accessible to investigators through user identification and a personal password and will become effective following confirmation of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patients will be randomly assigned (1:1) to one of the two study groups according to the antiseptic solution used to disinfect the skin before surgery and during all dressing changes (figure 1). To avoid randomisation of a patient with cancelled surgery, this will be done a few days before or on the day of surgery.

Interventions

CHG group: The surgical site will be largely disinfected using applicators of 2% CHG70% isopropanol (ChloraPrep, CareFusion). According to local practices, antiseptic application will be preceded (two-step procedure) or not (one-step procedure) by skin scrubbing with 4% CHG (Hibiscrub, Molnlycke Health Care).

PVI group: The surgical site will be largely disinfected using sterile gauzes soaked with 5% PVI–69% ethanol (Bétadine alcoolique, MEDA Pharma SAS). According to local practices, antiseptic application will be preceded (two-step procedure) or not (one-step procedure) by skin scrubbing with 4% PVI (Bétadine Scrub, MEDA Pharma SAS).

In order to ensure respect of treatment group and to achieve traceability, individual boxes containing all disinfecting products required for disinfecting the skin before surgery and during patient care will be supplied. According to randomisation, each patient will have his own box, which will follow him from the operating room to hospital discharge.

The following care procedures will be applied to all patients and controlled throughout the duration of the study:

At least one total body shower during the 24 hours preceding surgery, using either plain soap or antiseptic soap.

Hair removal if required with clipper (no shaving) before surgery.

Antibiotic prophylaxis according to the French recommendations16 applied 30 min prior to incision, and with appropriate reinjection if required for prolonged surgery. No readministration during the postoperative period.

Antiseptic application by moving back and forth for at least 30 s, starting at the incision site and then extending to the entire work area. The surgical field extends from the jaw to the shoulders and down to the tip of both feet in case of surgery with harvesting of the saphenous vein. In the event of surgery without saphenous vein harvesting, the field stops at the knees. According to local practices, the antiseptic solution will be applied once or twice, preceded or not by skin scrubbing with an antiseptic soap.

Application of large sterile drapes once the work area is dry.

In each centre, before the beginning of the inclusion, a list of care policy for prevention of SSI (Staphylococcus aureus decontamination, antimicrobial-coated sutures, adhesive incises drapes with antiseptics, antimicrobial dressings and so on) will be established and will not be modified throughout the duration of the study.

Study outcomes

Primary endpoint

The primary outcome will be the proportion of patients undergoing either any re-sternotomy occurring between day 0 and day 90 after surgery or any reoperation on saphenous vein/radial artery site occurring between day 0 and day 30 after surgery or both.

Secondary endpoints

Proportion of patients with mediastinitis according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria17 occurring by day 90 after surgery and pathogens involved.

Proportion of patients with deep incisional SSI at saphenous vein/radial artery site, superficial incisional SSI at sternal or saphenous vein/radial artery sites according to the CDC criteria17 occurring by day 30 after surgery and the pathogens involved.

Proportion of patients with SWI requiring reoperation, occurring by day 90.

Proportion of patients with SSI at saphenous vein/radial artery site requiring reoperation, occurring by day 30.

Proportion of patients with unexpected need for readmission to intensive care unit (ICU) or re-hospitalisation.

Duration of ICU stay.

Duration of stay under mechanical ventilation.

Duration of hospital stay.

Duration of rehabilitation unit stay.

All-cause mortality at day 90 of surgery.

Proportion of patients with local and systemic side effects possibly linked to antiseptic use.

Two independent assessors masked to the antiseptic group and to the event will review all postoperative reports of patients needing re-sternotomy during the 90 days following surgery and/or reoperation on saphenous vein/radial artery site during the 30 days following surgery. They will classify the case-reports as follows:

SWI (mediastinitis or superficial sternal SSI).

And/or deep or superficial saphenous vein/radial artery SSI.

Or no SSI according to CDC criteria.

Disagreements between the two assessors will be resolved by consensus conference among all outcome assessors.

Data collection

Independent clinical research assistants will be available at each participating hospital to help in running the study and with data collection. Study documents will be deidentified and stored for 15 years, as per the protocol for non-clinical trial notification interventional studies. Data will be entered into the web-based eCRF (CSOnline, Clinsight) and electronically stored on double password-protected computers. Hard copies of data (clinical research files) will be stored in a secure locked office. All personnel involved in data analysis will be masked to study groups. Only the principal investigators and the statisticians will have access to the final data set. The following data will be recorded.

Baseline characteristics and preoperative data

Demographic data (age, gender, height, weight and body mass index); American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status; EuroSCORE II; comorbidities (active smoking; insulin-dependent diabetes; non-insulin-dependent diabetes; hypertension; hypercholesterolaemia; chronic renal failure; COPD; history of cardiac surgery; atrial fibrillation); key laboratory findings; use of preoperative S. aureus decontamination; hair removal and modality; number and type (soap with or without antiseptic) of preoperative showers.

Intraoperative data

Type of surgery of the heart (valve, coronary, combined surgery, other) or of the aorta; type of scheduling (elective, semi-elective or emergency); skin scrubbing before skin antisepsis; number of antiseptic applications; number of antiseptic products used; antibiotic prophylaxis: molecule, dose, timing and possible redosing; use of iodophor-impregnated incise drapes; number of internal thoracic arteries sampled; sampling of saphen vein or radial artery, site open or endoscopic; length of surgery (incision to closure); duration of cardiopulmonary bypass; minimal and maximal body temperature during surgery; volume infused during surgery and type; number and types of blood transfusion during surgery; type of vasopressor administered during surgery; use of mechanical cardiac support (extra-corporeal life support (ECLS) or intra-aortic balloon pump); adverse events (especially local and systemic side effects possibly linked to antiseptic use).

Postoperative data until hospital discharge

Type and number of blood products given during the 48 hours following surgery; type and length of vasopressor and/or inotropic drugs administered during the 48 hours following surgery; use of mechanical cardiac support (ECLS, intra-aortic balloon pump); atrial fibrillation episode; number and results of blood cultures; number, type and results of bacteriological sampling at surgical site; wound status at surgical site (until dressing withdrawal): local signs of infection (local incisional pain/tenderness, localised redness, heat or swelling, purulent drainage from the superficial incision, superficial/deep incision spontaneously or deliberately opened by the surgeon), status of dressing, date of dressing changes; physical examination (temperature, chest pain, sternal instability); antibiotics used (molecule, duration and indication); results of blood samples (standard lab values); duration of mechanical ventilation; length of stay in ICU, surgical ward and high dependency unit; date of hospital discharge; reoperation at sternal site or saphenous vein/radial artery site occurring after surgery (date and reason); SSI occurrence: type (superficial, deep, organ-space), site and date and hour of SSI diagnosis; adverse events (especially local and systemic side effects possibly linked to antiseptic use) and survival status (if the patient is deceased, date of death).

Postoperative data monthly after surgery (until 90 days following surgery)

Phone contact: date; SSI occurrence, date of diagnosis, site and type; planned or unplanned surgical consultation; need for hospital readmission: date, total duration of hospital stay; need for reoperation at sternal site (within 90 days following surgery) or at saphenous vein/radial artery site (within 30 days following surgery): date, reason; date of rehabilitation unit discharge and survival status (if the patient is deceased, date of death).

Safety

According to the French Public Health Code, all suspected unexpected serious adverse events will be reported to the Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament (ANSM). Adverse events will be evaluated at each visit during clinical interview and physical examination. In agreement with ANSM, all serious adverse events related to heart disease (except infections) and not related to antiseptic use will not be declared immediately but will be reported in the eCRF. Each serious adverse event will be described as completely as possible on the report form designed for this purpose. The initial report will be followed by complementary reports of relevant information as soon as possible.

Sample size calculation

Assuming a 6% reoperation rate in the PVI group,61863 patients in each treatment arm will be required to demonstrate a 33% reduction of reoperation rate with the use of 2% CHG–70% isopropanol, with statistical risks at 5% and 20% for type I and type II errors, respectively. The sample size calculation is based on the two-sided test. We are planning to enrol 4100 patients to take into account a maximum patient loss of 10%.

Statistical analysis

The data will be analysed blindly on an intention-to-treat basis. No interim analysis is planned. Demographic data will be described as number and percentage or median and IQR and compared with the χ² test or Mann-Whitney test, as appropriate. For primary analysis, incidence of reoperation between groups will be compared with χ² test. We will assess antiseptic efficacy with a marginal Cox model and adjusted for covariates that will be significantly imbalanced between groups. We will calculate HR and 95% CIs, as well as incidence density and Kaplan-Meier estimates. Proportions of each secondary endpoint assessed at day 30 and day 90 will be compared using similar principles. We will use χ² tests. A multiple logistic regression will be computed with covariates clinically relevant according to our outcomes (Centre; patients’ characteristics: age, gender, body mass index, EuroSCORE II, active smoking, insulin-dependent diabetes, use of preoperative S. aureus decontamination; Intraoperative data: type of surgery of the heart (valve, coronary, combined surgery, other) or of the aorta, type of scheduling (elective, semi-elective or emergency), skin scrubbing before skin antisepsis; number of antiseptic application, use of iodophor-impregnated incise drapes, number of internal thoracic arteries sampled, length of surgery, duration of cardiopulmonary bypass, minimal body temperature during surgery, volume infused during surgery, use of mechanic cardiac support) and with covariates statistically relevant (covariates with difference between groups <0.20 in the univariate analysis). All tests will be two-tailed, stratified by centre and unadjusted for multiple comparisons. Analyses will be done with SAS V.9.4 and R software.

Patient and public involvement

The ethical committee, composed of patients’ representatives, considered if the research is conformed to patients’ priorities. Each patient, admitted in a participating centre, is screened and enrolled by the attending physicians according to the protocol. The burden of the intervention is assessed by the patients themselves. Each patient, after the end of the study, will have the opportunity to obtain the results if they are interested; all information is provided at inclusion in consent and information forms. No patient was involved in the recruitment to and the conduct of the study.

Ethics and dissemination

Research ethics

The clinical trial will be carried out in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the guideline for Good Clinical Practice of the International Conference on Harmonization, in accordance with the French law No. 2012–300 of 5 March 2012 on research involving the human person and with the Clinical Trials Directives 2001/20/EC and 2005/28/EC of the European Parliament.

Consent

Written informed consent will be requested from each patient prior to enrolment. The investigators will provide clear and precise information to the patient about the protocol before asking him/her for written informed consent.

Confidentiality

People with direct access to the data will take all necessary precautions to maintain confidentiality. All data collected during the study will be rendered anonymous. Only initials and inclusion number will be registered.

Dissemination policy

The results of the study will be released to the participating physicians, referring physicians and medical community no later than 1 year after completion of the trial through presentation at scientific conferences and publication in peer-reviewed journals.

The main manuscript will mention the name of the sponsor, and all trial sites will be acknowledged. All investigators having included or followed participants in the study will appear with their names under ‘the CLEAN 2 investigators’ in an appendix to the final manuscript. Authorship will be done in accordance with the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal. No professional writer will be used.

Discussion

This study will provide new knowledge in the field of SSI prevention, addressing questions raised by the Cochrane review on preoperative skin antiseptics aimed at preventing surgical wound infections after clean surgery.18 In clean surgery, the majority of pathogens responsible for infectious complications come from the skin, and skin disinfection has the potential to reduce both the frequency and severity of SSI in proportion to the efficacy of disinfection. The choice of cardiac surgery is based on the severity of SSI with this surgery, especially mediastinitis, which frequently requires reoperation. We selected centres with experience in SSI prevention studies and already applying all the other SSI prevention measures recommended by our national guidelines. Their number is limited so as to ensure high quality of follow-up by independent clinical research assistants. Stratified randomisation will protect against bias linked to potential variability in surgical practices between centres. Individual boxes containing allocated disinfecting products will follow the patient from the operating room to hospital discharge to ensure respect of treatment group and to facilitate product traceability. The choice of reoperation as the main endpoint is not subject to evaluation bias in an open study.

Our study will have several limitations. First, masking will not be feasible, because the two antiseptic solutions differ in both colour and formulation. However, the microbiologists who will perform all microbiological cultures will be unaware of treatment allocation. More importantly, all cases of suspected SSI will be reviewed by masked independent assessors based on internationally accepted definitions.17 Second, the two antiseptic solutions contain different alcoholic components and use different application methods. However, these products will be used in their commercially available formulations in France and as recommended by our national guidelines. Further studies will be necessary to determine the more efficient type and concentration of alcohol to be combined with CHG or PVI as well as the optimal concentration of CHG and PVI and optimal method for antiseptic application. Third, we have chosen incidence of reoperation as the primary endpoint. They can be due to non-infectious causes such as postoperative bleeding, valve dysfunction and so on, for which the impact of skin disinfection is probably low. However, their main advantage is to be a strong unquestionable endpoint not subject to assessment bias in an open trial. Fourth, adhesion to the study protocol will not be regularly checked by formal audits. However, the healthcare providers will attend training sessions designed to homogenise skin preparation practices across hospitals before starting the study, and independent clinical research assistants will be available at each participating hospital to monitor the conduct of the trial. Moreover, all study centres will be required to follow French recommendations similar to CDC recommendations for prevention of SSI with no modification allowed during the study period.

We assumed a 33% reduction in reoperation with the use of alcoholic CHG in our study. This choice may appear too ambitious. However, it is based on the existence of several surgical sites in the majority of patients, the major role of SSI in reoperation and the expected effect of antiseptic choice on SSI prevention. In clean contaminated surgery, a 50% reduction in SSI with alcoholic CHG use has been reported in digestive7 or obstetrical9 surgery. In these types of surgery, a significant fraction of pathogens involved comes from the digestive or gynaecological flora not accessible to the action of antiseptics. In intensive care, an 85% reduction in infections related to short-term central venous and arterial catheters has been reported with alcoholic CHG use.19 As in clean surgery, the skin flora is the main reservoir of pathogens involved in these infections, and the effectiveness of skin disinfection is essential to prevent them. In total, if we consider that among the 6% of reoperation in the PVI group, half are related to an SSI (which is probably underestimated), we can expect an incidence of reoperation in the CHG group between 3.5% (hypothesis very favourable to alcoholic CHG use) and 4.5% (hypothesis not very favourable to alcoholic CHG use). In the event of negative results, the choice of the antiseptic strategy could be based on the incidence of secondary endpoints in both arms of our study, and finally, on the cost of antiseptic strategies, even if it is insignificant compared with that of SSI.

We will conduct the first large-scale randomised trial adequately powered to compare the efficacy and safety of CHX–alcohol over PVI–alcohol in reducing SSI after clean surgery. Reducing SSI after surgery is associated with decreased length of hospital stay, mortality and overall costs and increased patient satisfaction,4 which should benefit both the patient and the community. The trial is multicentre, and almost all eligible patients will be included and will benefit from all the measures recommended by our national guidelines (similar to CDC guidelines) to prevent SSI. As a result, our findings will be reasonably extended to other cardiac surgery centres, to other clean surgeries and, more generally, to all surgical procedures performed worldwide, even if the proportion of skin pathogens involved in SSI is lower than in clean surgery.

Trial status

The current protocol is V.3.0 dated 12 September 2018. The trial is currently recruiting patients. The inclusion process started on 17 September 2018 and the number of patients included to date (12 February 2019) is 311. The estimated length of inclusion time is 18 months.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MB and OM conceived the study, coordinated its design, wrote the manuscript and drafted the manuscript. PC, TK, LC, MD, PD, VE, EF, DL, PL, NN, JYN, JCR, BR, SR, JCL and JFT read and were involved in critical appraisal and revision of the manuscript. SR and JFT provided statistical expertise. All authors approved the final manuscript prior to submission.

Funding: This work is being funded by unrestricted research grants from the French Ministry of Social Affairs and Health (#16-0619) and CareFusion/ Becton Dickinson.

Competing interests: OM has received grant support from 3M and Carefusion-BD and honoraria for giving lectures from 3M and Carefusion-BD. Funders will have no role in the trial initiation, study design, choice of antiseptic products, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report.

Ethics approval: Ethical aspects of this research project have been approved by the ethics committee of Ambroise Paré Hospital (CPP Ile de France VIII, Boulogne-Billancourt, France).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Report on the burden of endemic health care-associated infection worldwide. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Annual epidemiological report 2014. Antimicrobial resistance and healthcare-associated infections. 2015. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/antimicrobial-resistance-annual-epidemiological-report.pdf (Accessed 26 Apr 2016).

- 3. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Surveillance of surgical site infections in Europe 2010–2011. Eur. Cent. Dis Prev. Control 2013. http://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/SSI-in-europe-2010-2011.pdf (Accessed 24 Oct 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization. Global guidelines on the prevention of surgical site infection. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Finkelstein R, Rabino G, Mashiah T, et al. . Surgical site infection rates following cardiac surgery: the impact of a 6-year infection control program. Am J Infect Control 2005;33:450–4. 10.1016/j.ajic.2005.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lemaignen A, Birgand G, Ghodhbane W, et al. . Sternal wound infection after cardiac surgery: incidence and risk factors according to clinical presentation. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015;21:674.e11–8. 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Darouiche RO, Wall MJ, Itani KM, et al. . Chlorhexidine-Alcohol versus povidone-iodine for surgical-site antisepsis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:18–26. 10.1056/NEJMoa0810988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ngai IM, Van Arsdale A, Govindappagari S, et al. . Skin Preparation for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection After Cesarean Delivery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:1251–7. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tuuli MG, Liu J, Stout MJ, et al. . A randomized trial comparing skin antiseptic agents at cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med 2016;374:647–55. 10.1056/NEJMoa1511048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Park HM, Han SS, Lee EC, et al. . Randomized clinical trial of preoperative skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone-iodine. Br J Surg 2017;104:e145–50. 10.1002/bjs.10395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Broach RB, Paulson EC, Scott C, et al. . Randomized controlled trial of two alcohol-based preparations for surgical site antisepsis in colorectal surgery. Ann Surg 2017;266:946–51. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee I, Agarwal RK, Lee BY, et al. . Systematic review and cost analysis comparing use of chlorhexidine with use of iodine for preoperative skin antisepsis to prevent surgical site infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010;31:1219–29. 10.1086/657134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Noorani A, Rabey N, Walsh SR, et al. . Systematic review and meta-analysis of preoperative antisepsis with chlorhexidine versus povidone-iodine in clean-contaminated surgery. Br J Surg 2010;97:1614–20. 10.1002/bjs.7214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kamel C, McGahan L, Polisena J, et al. . Preoperative skin antiseptic preparations for preventing surgical site infections: a systematic review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2012;33:608–17. 10.1086/665723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Allegranzi B, Bischoff P, de Jonge S, et al. . New WHO recommendations on preoperative measures for surgical site infection prevention: an evidence-based global perspective. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16:e276–87. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30398-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. SFAR. Antibioprophylaxie en chirurgie et médecine interventionnelle (patients adultes). 2018. https://sfar.org/antibioprophylaxie-en-chirurgie-et-medecine-interventionnelle-patients-adultes-maj2018/ (Accessed 7 Jan 2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Healthcare Safety Network. Surveillance definitions for specific types of infections. https://www-cdc-gov.gate2.inist.fr/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/17pscnosinfdef_current.pdf (Accessed 8 Jul 2018).

- 18. Edwards PS, Lipp A, Holmes A. Preoperative skin antiseptics for preventing surgical wound infections after clean surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004:CD003949 10.1002/14651858.CD003949.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mimoz O, Lucet JC, Kerforne T, et al. . Skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine-alcohol versus povidone iodine-alcohol, with and without skin scrubbing, for prevention of intravascular-catheter-related infection (CLEAN): an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, two-by-two factorial trial. Lancet 2015;386:2069–77. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00244-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.