Abstract

Congenital muscular dystrophies (CMD) are a heterogeneous group of disorders caused by mutations in musculoskeletal proteins. The most common type of CMD in Europe is Merosin-deficient CMD caused by mutations in laminin-α2 protein. Very few studies reported pathogenic variants underlying these disorders especially from Africa. In this study we report a rare variant (p.Arg148Trp, rs752485547) in LAMA2 gene causing a mild form of Merosin-deficient CMD in a Sudanese family. The family consisted of two patients diagnosed clinically with congenital muscular dystrophy since childhood and five healthy siblings born to consanguineous parents. Whole exome sequencing was performed for the two patients and a healthy sibling. A rare missense variant (p.Arg148Trp, rs752485547) in LAMA2 gene was discovered and verified using Sanger sequencing. The segregation pattern was consistent with autosomal recessive inheritance. The pathogenicity of this variant was predicted using bioinformatics tools. More studies are needed to explore the whole spectrum of mutations in CMD in patients from Sudan and other parts of the world.

Key words: congenital muscular dystrophy, Sudan, exome sequencing, novel variant

Introduction

Congenital muscular dystrophies (CMD) are a heterogeneous group of disorders with phenotypic and genetic overlaps (1) caused by defects in structural proteins of skeletal muscle fibers e.g. Merosin, integrin, α-dystroglycan and others (2) molecular understanding of the congenital muscular dystrophies (CMDs. These diseases present commonly in early childhood with floppiness, progressive muscle weakness and skeletal deformities that severely impair the quality of life (3, 4). The heterogeneity in clinical presentation of CMD makes it difficult to estimate the burden of these diseases and certainly underestimates their prevalence (5).

Merosin-deficient CMD type 1A (MDC1A) is one of the most common forms of CMD accounting for 30-40% of cases in Europe (6). It is caused by mutations in laminin-alpha 2 (LAMA2) gene in chromosome 6q22-q23. Patients may present with muscle weakness, joint contractures, facial dysmorphism, peripheral motor neuropathy, epilepsy, developmental delay, elevated creatine kinase and white matter changes in brain MRI. The onset of symptoms, clinical presentation and partial or complete deficiency of laminin shows a broad range of variability in this type of dystrophy. Mild forms of CMD1A might resemble limb-girdle muscular dystrophy with peripheral motor neuropathy. Duplications, missense, nonsense and splice site mutations have been described. Thus, genetic analysis is necessary even in the presence of LAMA2 protein in muscle biopsy (7).

Studies underlying genetics of CMD in general and the merosin deficient type (MD-CMD) in particular are relatively deficient especially in Africa where lack of expertise and high throughput technologies makes it difficult to discover novel candidate variants despite the well-known genetic heterogeneity of African populations (8)particularly in Africa, are important for reconstructing human evolutionary history and for understanding the genetic basis of phenotypic adaptation and complex disease. African populations are characterized by greater levels of genetic diversity, extensive population substructure, and less linkage disequilibrium (LD. In this article we report a rare variant (p.Arg148Trp, rs752485547) in LAMA2 gene causing a mild form of Merosin-deficient CMD in a Sudanese family.

Materials and methods

Case presentation

Two Sudanese patients born to first degree consanguineous parents diagnosed with CMD since childhood were investigated. Patient 1 (the proband) was diagnosed at age 3 years. Patient 2 was diagnosed at age 4 years. Both patients presented with poor motor development, proximal muscle weakness, hypotonia and recurrent parasthesia but normal intellectual development. Patient 2 also suffered from epilepsy. There was a positive family history (a maternal uncle who passed away from the disease at age 36). The serum of the two patients showed elevation in CK level (120 units/ml, Normal: < 60 units/ml) and nerve conduction studies showed evidence of peripheral neuropathy. Patients refused to take a muscle biopsy for immunohistochemistry.

Five mL of peripheral venous blood was obtained from both patients, the parents, and two healthy siblings. Genomic DNA was extracted using guanidine chloride method as described in (9).

Whole exome sequencing

Exome sequencing was performed for two patients and a healthy elder sibling. The genomic DNA samples were enriched using TrueSeq library preparation kit v3 targeting a total length of 45Mb of the human coding exons. The samples were paired-end sequenced on an illumina HiSeq 2000 platform. The sequencing service was provided by Macrogen Inc. (Korea). The trimmed reads were aligned to the human genome assembly hg19 using bwa v0.7.12(10). The duplicates were removed using samtools v1.2(11). The alignment metrics were collected using Picard (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). The percentage of the mapped unique reads was around 90%. The mean target coverage ranged around 90x for the three samples with ~ 90% of target bases covered at least 10x and 85% covered at least 20x. The variant calling was performed jointly for the three samples using freebayes v0.9.21(12). The VCF file was annotated using VEP v84(13) and loaded to Gemini v0.17(14), then filtered for rare (ExAC MAF < 0.01) potentially pathogenic variants (CADD score > 10) that follow an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern (15, 16). A total of four shared runs of homozygosity (ROH) were identified using Homozygosity Mapper (17). We prioritized the variants that have a loss of function effect (stop-effect, frameshifts, splice-sites) or a damaging effect (both PPh2 damaging prediction and SIFT deleterious prediction) that are located in one of these homozygous run. This strategy effectively narrowed down the number of candidate variants to a single variant.

Sanger sequencing

For confirmation of genotypes, we performed Sanger sequencing for the candidate variant in the proband, his parents and a healthy sibling. Unfortunately, patient 2 passed away at age 36 years before the confirmation of his genotype through Sanger sequencing. Forward and reverse primers were designed using primer 3(18). The primers used were: F 5’ TCCCTAGGTGTTCCAGATCG, R 5’ TTGTAAAGCGTTAGGCACTCC using the following PCR conditions: initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 93°C for 30 seconds, 58.5°C for 30 seconds and 72°C for 20 seconds, with a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes, to yield a PCR product of 153 base pairs in length. The PCR product was sequenced by Macrogen Inc (Korea). The resulting DNA sequences were aligned to the reference LAMA2 DNA sequence from NCBI database using Bioedit software (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html). The reference sequence (NM_000426.3) has been used for LAMA2 variants.

Results

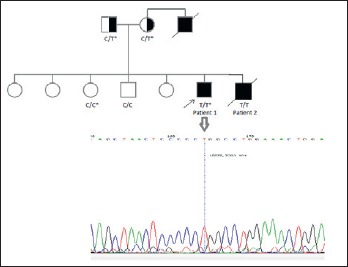

Whole exome sequence analysis revealed a rare C to T substitution in LAMA2 gene (rs752485547, p.Arg148Trp) shared by the two patients but not their healthy brother. The variant was confirmed using standard Sanger sequencing and segregation analysis confirmed an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern (Fig. 1). The parents had a heterozygous (carrier) genotype; the proband was homozygous for the mutant variant and their healthy sister had a homozygous wild type genotype.

Discussion and conclusions

In this article we reported an ulra-rare missense variant in LAMA2 gene (NM_000426.3:c.442C>T) causing a mild form of congenital muscular dystrophy in a Sudanese family. The variant has no reported clinical significance so far. It has a minor allele count of 3 (minor allele frequency of 0.00001218) according to the gnomAD database (14). It is moderately conserved among vertebrates (GERP rejected substitution score = 4.14) and predicted to be deleterious by more than five bioinformatic algorithms (SIFT, PPh2, Condel, Provean, FATHMM, MA) its amino acid change (p.Arg148Trp) is located in the Laminin N-terminal domain of LAMA2 protein. LAMA2 is important for cellular migration and organization during embryonic development (19). It acts as a mediator between extracellular and intracellular matrices (19). Changing one amino acid residue in a protein into another has variable impact on protein structure and function. Arginine is a positively charged amino acid and its replacement with Tryptophan; a hydrophobic amino acid and the largest in size will probably impairs the integrity of the protein especially in high and moderately conserved sites. According to the latest ACMG guidelines, this variant has at least two moderate (located in a mutational hot spot and/or critical and well-established functional domain, and at extremely low frequency in public databases) and two supporting (co-segregation with disease in multiple affected family members in a gene definitively known to cause the disease, and multiple lines of computational evidence support a deleterious effect on the gene or gene product) criteria of pathogenicity (20). We therefore recommend the annotation of this variant as likely pathogenic.

Mutations in LAMA2 gene causing CMD have been reported frequently in the literature from many parts of the world (21-29), especially in the past few years (22-26). However, studies are still lacking in Sub-Saharan Africa. Only one study has reported a novel mutation in LAMA2 gene (NG_008678.1:g.437812T>C) in a Sudanese family (along with three other Saudi families) suggesting a founder haplotype in the region of Middle-East or Sudan (30). On the contrary, the current variant was seen in three different populations in gnomAD (once in each of the South Asian, Latino and non-Finish European populations). However, this part of the gene seems to represent a mutational hotspot. This variant (NM_000426.3:c.442C>T) is flanked by multiple rare and ultra-rare variants. A closely located variant (NM_000426.3:c.444dupG) is a known pathogenic insertion. Identification of causative mutations will certainly increase our understanding of the origin of disease-causing variants, molecular pathogenesis of the disease and perhaps new therapeutic modalities.

Figures and tables

Figure 1.

The pedigree of a Sudanese family with two patients with congenital muscular dystrophy. The arrow indicates the proband. The genotypes of the patients, parents and two healthy siblings are shown. The genotypes marked with (*) are detected or confirmed by Sanger sequencing. The electropherogram shows the result of Sanger sequencing in the proband.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Ms. Abda Alfatih from the Institute of Endemic Diseases, University of Khartoum, Sudan for her valuable assistance in lab work.

Footnotes

Funding

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

All data related to this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author’s contributions

MA and YB made substantial contributions to the design, administration and conceptualization of the study, interpretation of data and critically revising and drafting the manuscript. MK analyzed the data provided review and editing to the manuscript. MA, YB, MK, MO, OS, MS and MI participated in project conceptualization, data analysis and curation, review and editing. All authors approved the submission of the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by ethical committee, Institute of Endemic Diseases, University of Khartoum, Sudan. Informed consent was obtained from each patient and family member before participation in the study.

Consent for publication

All participants (or parents/legal guardians in case of minors) provided consent for the publication of their clinical details.

Conflict of interest

The Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Sparks SE, Quijano-Roy S, Harper A, et al. Congenital Muscular Dystrophy Overview [Internet]. GeneReviews(®). University of Washington, Seattle: 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendell JR, Boué DR, Martin PT. The congenital muscular dystrophies: recent advances and molecular insights. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2006;9:427-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falsaperla R, Ruggieri M, Parano E, et al. Congenital muscular dystrophy: from muscle to brain. Ital J Pediatr 2016;42:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang PB, Griggs RC. Advances in muscular dystrophies. JAMA Neurol 2015;72:741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Data and Statistics | Muscular Dystrophy | NCBDDD | CDC (https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/musculardystrophy/data.html).

- 6.Merosin-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy, autosomal recessive (MDC1A, MIM|[num]|156225, LAMA2 gene coding for |[alpha]|2 chain of laminin) doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200743. ( http://www.nature.com/ejhg/journal/v10/n2/full/5200743a.html) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Beytía M de los A, Dekomien G, Hoffjan S, et al. High creatine kinase levels and white matter changes: clinical and genetic spectrum of congenital muscular dystrophies with laminin alpha-2 deficiency. Mol Cell Probes 2014;28:118-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell MC, Tishkoff SA. African genetic diversity: implications for human demographic history, modern human origins, and complex disease mapping. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2008;9:403-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pramanick D, Forstov J, Pivec L. 4 M guanidine hydrochloride applied to the isolation of DNA from different sources. FEBS Lett 1976;62:81-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. 2013. (http://arxiv.org/abs/1303.3997).

- 11.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009;25:2078-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrison E, Marth G. Haplotype-based variant detection from short-read sequencing. 2012. (https://arxiv.org/pdf/1207.3907.pdf).

- 13.1McLaren W, Gil L, Hunt SE, et al. The Ensembl variant effect predictor. Genome Biol 2016;17:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paila U, Chapman BA, Kirchner R, et al. GEMINI: integrative exploration of genetic variation and genome annotations. Gardner PP, Ed. PLoS Comput Biol 2013;9:e1003153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 2016;536:285-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kircher M, Witten DM, Jain P, et al. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat Genet 2014;46:310-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seelow D, Schuelke M, Hildebrandt F, et al. Homozygosity mapper – an interactive approach to homozygosity mapping. Nucleic Acids Res 2009;37:W593-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, et al. Primer3 – new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40:e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li S, Edgar D, Fissler R, et al. The role of laminin in embryonic cell polarization and tissue organization. Dev Cell 2003;4:613-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 2015;17:405-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson I, Stojkovic T, Allamand V, et al. Laminin α2 deficiency-related muscular dystrophy mimicking emery-dreifuss and collagen VI related diseases. J Neuromuscul Dis 2015;2:229-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhowmik AD, Dalal AB, Matta D, et al. Targeted next generation sequencing identifies a novel deletion in LAMA2 gene in a Merosin deficient congenital muscular dystrophy patient. Indian J Pediatr 2016;83:354-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turner C, Mein R, Sharpe C, et al. Merosin-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy: a novel homozygous mutation in the laminin-2 gene. J Clin Neurosci 2015;22:1983-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bendixen RM, Butrum J, Jain MS, et al. Upper extremity outcome measures for collagen VI-related myopathy and LAMA2-related muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord 2017;27:278-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim MW, Jang DH, Kang J, et al. Novel Mutation (c.8725T>C) in two siblings with late-onset LAMA2-related muscular dystrophy. Ann Lab Med 2017;37:359-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding J, Zhao D, Du R, et al. Clinical and molecular genetic analysis of a family with late-onset LAMA2-related muscular dystrophy. Brain Dev 2016;38:242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nichols C, Jain MS, Meilleur KG, et al. Electrical impedance myography in individuals with collagen 6 and laminin α-2 congenital muscular dystrophy: a cross-sectional and 2-year analysis. Muscle Nerve 2017. (http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/mus.25629). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Fontes-Oliveira CC, Steinz M, Schneiderat P, et al. Bioenergetic impairment in congenital muscular dystrophy type 1a and leigh syndrome muscle cells. Sci Rep 2017;7:45272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dean M, Rashid S, Kupsky W, et al. Child neurology: LAMA2 muscular dystrophy without contractures. Neurology 2017;88:e199-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Di Blasi C, Bellafiore E, Salih MA, et al. Variable disease severity in Saudi Arabian and Sudanese families with c.3924 + 2 T > C mutation of LAMA2. BMC Res Notes 2011;4:534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]