Abstract

Background

Wickerhamomyces anomalus is a yeast associated with different insects including mosquitoes, where it is proposed to be involved in symbiotic relationships with hosts. Different symbiotic strains of W. anomalus display a killer phenotype mediated by protein toxins with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activities. In particular, a killer toxin purified from a W. anomalus strain (WaF17.12), previously isolated from the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles stephensi, has shown strong in vitro anti-plasmodial activity against early sporogonic stages of the murine malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei.

Results

Here, we provide evidence that WaF17.12 cultures, properly stimulated to induce the expression of the killer toxin, can directly affect in vitro P. berghei early sporogonic stages, causing membrane damage and parasite death. Moreover, we demonstrated by in vivo studies that mosquito dietary supplementation with activated WaF17.12 cells interfere with ookinete development in the midgut of An. stephensi. Besides the anti-sporogonic action of WaF17.12, an inhibitory effect of purified WaF17.12-killer toxin was observed on erythrocytic stages of P. berghei, with a consequent reduction of parasitaemia in mice. The preliminary safety tests on murine cell lines showed no side effects.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate the anti-plasmodial activity of WaF17.12 against different developmental stages of P. berghei. New studies on P. falciparum are needed to evaluate the use of killer yeasts as innovative tools in the symbiotic control of malaria.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13071-019-3587-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Wickerhamomyces anomalus, Plasmodium berghei, Anopheles stephensi, Killer toxin, Symbiotic control, Malaria

Background

Malaria is a mosquito-borne disease that kills about half a million people each year, predominantly children under five years of age. Plasmodium, the etiological agent of malaria, is transmitted to humans (vertebrate host) through the bite of a female Anopheles mosquito (vector and invertebrate host). Efforts to reduce morbidity and mortality have been impaired by drug and pesticide resistance and the lack of effective vaccines. To ameliorate the efficacy of malaria control efforts, innovative strategies are urgently needed [1, 2].

Plasmodium has a complex life-cycle including sexual and asexual developmental stages. It alternates a sporogonic phase in the mosquito with differentiation of zygotes, ookinetes, oocysts and sporozoites, and hepatic/erythrocytic phases in the vertebrate host where it multiplies different asexual stages, micro- and macro-gametocytes. This multifaceted phenotypic variability is advantageous for the parasite but hampers the development of new therapeutic drugs and/or prophylaxis, thus facilitating the spread of malaria.

In recent years, symbiotic control (SC) has been proposed as a possible strategy for preventing malaria [3]. SC is intended to block malaria transmission by reducing anopheline vector competence through symbiotic microbes that affect the development of the parasite in the mosquito midgut [4, 5]. Some bacteria, including Asaia, Wolbachia and Pantoea, and fungi such as Metarhizium, have been proposed for the SC of malaria [3, 6–8]. In this frame, the identification of killer yeasts that exert symbiotic functions in mosquitoes is very promising [9, 10].

Among the different isolated symbiotic killer strains, Wickerhamomyces anomalus offers a series of highly appealing features [11]. In fact, W. anomalus displays a wide antimicrobial property mediated by killer toxins (KTs) that exert an enzymatic activity targeting the cell-wall glucan components of bacteria, yeasts and protozoa [12]. Interestingly, W. anomalus is considered safe [13] and some environmental strains are used against spoilage microbes for food and beverage bio-preservation [14, 15].

Symbiotic strains of W. anomalus producing KTs have been identified in beetles, mosquitoes and sand flies where they are proposed to be involved in nutritional and/or protective functions [16–18]. In particular, the W. anomalus strain (WaF17.12) isolated from the malaria vector Anopheles stephensi, produces a KT (WaF17.12-KT) that has shown, as a purified product, a strong anti-plasmodial activity in vitro against sporogonic stages of the murine malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei, causing a surface membrane damage mediated by a β-glucanase activity [19]. WaF17.12-KT seems to be poorly expressed in the mosquito, although its production can be stimulated by selective media conditions, and yeast cultures can be reintroduced into the mosquito through diet [20]. Generally, the killer phenotype is activated or enhanced under stress conditions, as the competition with other microorganisms for environmental resources, whereas the host body is a niche favorable to the proliferation of yeast with good availability of food [21].

In the present study, in vitro and in vivo studies have been carried out to unveil interactions between the killer strain WaF17.12 and the murine malaria parasite P. berghei. The results demonstrated that the yeast affects different stages of the parasite development by WaF17.12-KT mediated mechanisms, both in mosquitoes and mice (vertebrate host). These outcomes validate WaF17.12 as an effective tool against P. berghei.

Methods

Yeasts and killer toxin production

Two W. anomalus (Wa) strains were used in the present study: WaF17.12, isolated from An. stephensi mosquitoes (KT-producer) [17]; and WaUM3, environmental strain (KT non-producer) [22]. Both strains were cultured in selective growth conditions to stimulate KT production: YPD broth (20 g/l peptone, 20 g/l glucose, 10 g/l yeast extract), buffered at 4.5 pH with 0.1 M citric acid and 0.2 M K2HPO4 [23]. Cells were incubated at 26 °C for 36 h at 70× rpm. To verify the activation of WaF17.12 and confirm KT expression, the supernatants of both yeast cultures were separated by chromatography and the obtained fractions analysed by western blot using the monoclonal mAbKT4 antibody specific for yeast KTs, as described in Valzano et al. [19] and Cappelli et al. [20]. The positive fraction obtained from WaF17.12 was named as WaF17.12-KT+ and the corresponding fraction isolated from WaUM3 (WaF17.12-KT-) was used as KT negative control.

Malaria parasites

Two P. berghei (murine malaria parasite) transgenic strains were used in the present work: PbCTRPp.GFP that expresses green fluorescent protein (GFP) during the early sporogonic phase of the parasite cycle [24], and PbGFPCON that expresses GFP throughout the whole parasite cycles both in the mosquito and vertebrate host [25]. The two parasites were differently used, depending on the type of assay. PbCTRPp.GFP was used for cultivating early sporogonic stages in vitro, whereas PbGFPCON, which is detectable during all the developmental stages, was used during in vivo experimentations. Both parasite strains were visualized using a fluorescence microscope (Axio Observer.Z1; Carl Zeiss, Milan, Italy).

Mice

BALB/c mice were maintained in the Animal Facilities of the University of Camerino at 24 °C, fed on standard laboratory mice pellets (Mucedola S.r.l., Milano, Italy) and provided with tap water ad libitum. Mice were used as P. berghei vertebrate hosts. Eight-week-old female mice (18–25 g) were infected with PbCTRPp.GFP or PbGFPCON directly by an intraperitoneal injection of 10% parasitaemic blood obtained from the tail of a donor mouse (acyclic passage). About 106 infected erythrocytes of the donor mouse were diluted in 200 μl of PBS (7.2 pH) and parasitaemia in injected mice was constantly monitored by optical microscope using a 10% Giemsa stained blood smear and fluorescence microscope (Axio Observer.Z1). Recipient mice were used for experimental purposes when showing 5% parasitaemia. All animal rearing and handling was carried out according to the Italian Legislative Decree (116 of 10/27/92) on the “use and protection of laboratory animals” and in agreement with the European Directive 2010/63/UE. The experimentation was approved by the Ethical Committee of University of Camerino.

Mosquitoes

Anopheles stephensi (Liston strain) mosquitoes were reared at 29 °C and 85–90% relative humidity with a 12:12 light-dark photoperiod in the insectarium of the University of Camerino. Immediately after emergence of adult mosquitoes, three cages, each containing 250 females, were set up for two trials. Newly emerged mosquitoes were fed ad libitum on a cotton pad soaked with 5% (w/v) sterile sucrose solution (control group), or 5% sucrose solution plus WaF17.12, or 5% sucrose solution plus WaUM3.

Killing activity assay of WaF17.12 against P. bergheiPb CTRPp.GFP sporogonic stages in vitro

Activated WaF17.12 and WaUM3 cultures were pelleted at 3000× g for 10 min and suspended in PBS (7.4 pH), whereas the supernatants were processed as described above. PbCTRPp.GFP cultures were obtained as follows: early sporogonic stages were developed in vitro incubating gametocytemic blood (20 µl) from a donor mouse showing 5% parasitaemia with ookinete-medium (180 µl) on microtiter plates. Ookinete-medium was prepared as described in Valzano et al. [19]. For the killing activity assay, parasite cultures were incubated with activated WaF17.12 (20 μl) or WaUM3 (20 μl) (yeasts final concentration 108 cell/ml) for 24 h at 19 °C in the dark (20 μl of PBS 7.4 pH was added to control wells). During incubation, gametocytes develop into fluorescent zygotes and ookinetes. The parasite number in each well was evaluated using a fluorescence microscope with a 40× objective (Axio Observer.Z1). Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Cell viability assay of P. berghei (PbCTRPp.GFP)

WaF17.12-KT+ and WaUM3-KT− fractions were tested in vitro against PbCTRPp.GFP early sporogonic stages to prove effective activation of yeasts and KT production. A viability assay was carried out incubating gametocytaemic blood with ookinete-medium and WaF17.12-KT+ (100 µg/ml KT final concentration) for 24 h at 19 °C. WaUM3-KT− was tested to evaluate possible effects due to other co-purified molecules, whereas control wells were prepared by adding PBS (7.4 pH). After incubation, parasites were treated with 20 µg/ml of the red-fluorescent dye propidium iodide (PI) (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, USA) in DNAse-free PBS, for 30 min at 20 °C, and visualized by fluorescence microscope (Axio Observer.Z1; Carl Zeiss, Milan, Italy). PI staining is used for identifying dead or damaged cells, because the dye penetrates cells with altered membranes where it intercalates DNA double strand, but it is effectively excluded from viable cells.

Killing activity assay of WaF17.12 against P. berghei PbGFPCON sporogonic stages in vivo

Three cages, each containing newly emerged female mosquitoes (n = 250), were set up with a cotton pad soaked with 5% sterile sucrose solution (control group), 5% sucrose solution plus WaF17.12 or 5% sucrose solution plus WaUM3. Yeasts were grown under stimulating conditions to produce KT as described above. Yeast cultures were centrifuged at 3000× g for 10 min at 4 °C, washed three times in 0.9% (w/v) NaCl solution, and suspended in 5% sucrose solution at a final concentration of 108 cells/ml. Food preparations were provided ad libitum to mosquitoes and the cotton pad was refreshed every two days for the duration of the experiment (21 days). To verify the presence of activated yeasts in the mosquito gut, an immunofluorescent assay (IFA) assay at 24 h, and 10 and 21 days post-infection was performed using a monoclonal anti-KT antibody (mAbKT4) obtained at a concentration of 2 mg/ml, as described by Cappelli et al. [20]. After six days, mosquitoes had a blood meal on a 5% parasitaemic mouse infected with PbGFPCON. Unfed mosquitoes were removed and cages were laid in a chamber at 19 °C and 95 ± 5% relative humidity for P. berghei development in the mosquito. Twenty-four hours after the blood meal (before ookinetes migrate across the midgut epithelium [26]), mosquito guts (n = 24 per cage) were dissected and individually homogenised in sterile PBS. Gut preparations were analysed through fluorescence microscopy using a 100× objective (Axio Observer.Z1) to detect PbGFPCON early sporogonic stages. The number of oocysts and sporozoites was evaluated, analysing guts and salivary glands (n = 10 per cage) 10 and 21 days post-infection, respectively. Experiments were performed twice.

WaF17.12-KT+ anti-plasmodial activity against P. berghei PbGFPCON erythrocytic stages in mice

A PbGFPCON infected mouse showing 5% parasitaemia was used for testing KT effects against P. berghei erythrocitic stages. The infected blood (100 µl) was incubated for 90 min at 25 °C with WaF17.12-KT+ (100 µg/ml KT), WaF17.12-KT+ (100 µg/ml KT) and mAbKT4 (100 µg/ml) [22], or 1× PBS at 7.2 pH (control). Preparations of treated blood samples (106 infected red blood cells) were inoculated into healthy eight-week-old female mice (18–25 g) (n = 5 mice per group). After 5 days, the parasitaemia of recipient mice was evaluated using a 10% Giemsa stained blood smear and optical microscope with 100× objective. The parasitaemia was controlled in the three groups, and variation was calculated as reported in Bonkian et al. [27]. The experiment was repeated twice.

Colorimetric MTT assay and Hepa 1–6 cellspropidium iodide (PI) staining

The colorimetric MTT assay was used to evaluate the cell viability in murine cell lines after treatment with WaF17.12-KT+. Hepa 1–6 cell line (mouse/liver/hepatoma from American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, USA) were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 using as a basal medium Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 IU/ml of penicillin and 100 μg of streptomycin (Lonza, Switzerland). Hepa 1–6 cells/ml (4 × 105) were seeded into 96-well plates and cultured with different doses of WaF17.12-KT+ (1, 5, 10, 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 µg/ml KT) for 24 h. Upon treatment, MTT (0.8 mg/ml) was added to the samples and incubated for 3 h. Then, the supernatants were discarded, and coloured formazan crystals dissolved with DMSO (100 μl/well) were read by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). Four replicates were used for each treatment. Hepa 1–6 cells, treated with 100 μg/ml KT or relative vehicle for 24 h were incubated with 2 μg/ml PI for 10 min at 37°C. Then, cells were harvested with Versene (EDTA), washed and analyzed using a FACScan cytofluorimeter with CellQuest software.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software. The differences between the groups in each experiment were compared using a Mann–Whitney U-test. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

WaF17.12 affects sporogonic stages of P. berghei in vitro and in vivo

The anti-plasmodial activity of WaF17.12-KT has been demonstrated in vitro against cultivated P. berghei sporogonic stages, but any direct effect of such KT-producing yeasts on the parasite development still required validation. Therefore, in the present study, in vitro and in vivo experiments were carried out to evaluate direct interactions between WaF17.12 and the murine malaria parasite P. berghei.

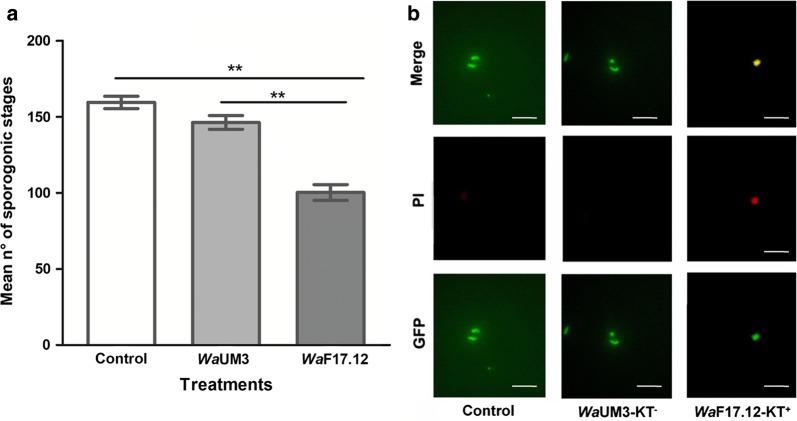

During in vitro tests, the number of developed parasites (zygotes and ookinetes) was counted and the mean values ± SEM from triplicate experiments are reported for each group (Fig. 1a). The treatment with WaF17.12 decreased the number of parasites by approximately 37.1%, whereas no significant differences between WaUM3 and control were detected. Such data suggests that the effect of W. anomalus on P. berghei sporogonic stages development was strain-dependent and attributable to the presence of the KT in the medium. To assess the activation of the WaF17.12 strain and to confirm KT expression, the supernatants from both strains were separated by ion-exchange chromatography and obtained fractions were analysed by western blot as described in the material and methods section. The KT containing fraction (WaF17.12-KT+) and the corresponding KT− (WaUM3-KT−) were collected and tested against cultured early P. berghei sporogonic stages (Fig. 1b). A cell viability assay was performed using the propidium iodide (PI) dye, to evaluate the effect of individual purified fractions on parasite development. Treatment with WaF17.12-KT+ induced an alteration of ookinetes morphology, characterized by bigger and more jagged shapes, and PI penetration in damaged and non-viable parasites. Conversely, WaUM3-KT− did not affect ookinetes, which showed a normal shape and no PI accumulation, similar to the control group, demonstrating that the anti-plasmodial activity of the WaF17.12-KT+ fraction was specific and not due to the presence of other co-purified molecules.

Fig. 1.

WaF17.12 in vitro killing activity against sporogonic stages of PbCTRPp.GFP (a) and cell viability assay (b). a Numbers of parasites developed by cultural method from gametocytemic mice bloodare reported after 24 h of incubation at 19 °C in the presence of WaUM3 (108 yeast cells/ml), WaF17.12 (108 yeast cells/ml) and PBS (control group). Mean values ± SEM were estimated from triplicate experiments and statistical significance expressed as a P-value (Mann–Whitney test: Control vs WaUM3: U(9) = 81, Z = 4.101, P = 0.0041; Control vs WaF17.12: U(9) = 81, Z = 4.101, P = 0.0041). **P < 0.01. b Fluorescence microscope images of ookinetes treated with the WaF17.12-KT+ (containing 100 µg/ml KT) or WaUM3-KT− fraction. Data show an abnormal morphology and PI accumulation only in toxin-treated parasites. Scale-bars: 20 µm

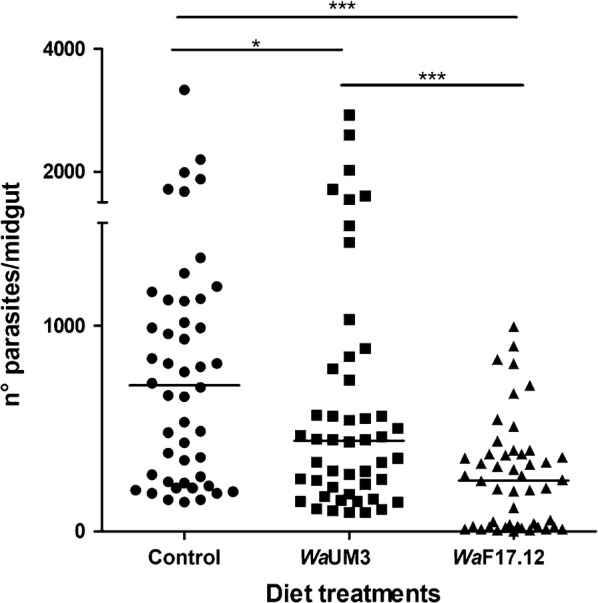

These findings prompted additional in vivo studies on the evaluation of the WaF17.12 strain anti-plasmodial activity in An. stephensi. The anti-plasmodial activity results confirmed the ability of WaF17.12 to abundantly colonize the An. stephensi gut, whereas no KT signal was detected in mosquitoes treated with WaUM3 and in the control group. PbGFPCON early sporogonic stages in the midgut lumen of mosquitoes colonized with activated yeast cultures and in control groups, were counted 24 h post-infection and the median values (m) obtained from two independent experiments are reported (Fig. 2). Mosquitoes colonized with WaF17.12 developed 65.2% fewer parasites than the control group (m = 710 and m = 247, respectively) and 43.9% fewer parasites than the WaUM3 group (m = 440). Differently from the in vitro analysis, a significant decrease in parasite number of 38.0% with respect to the control was also detected in mosquitoes colonized with WaUM3, indicating a non-KT related anti-plasmodial activity of this strain.

Fig. 2.

WaF17.12 inhibitory effect on early sporogonic stages of PbGFPCON in An. stephensi. Number of parasites (zygotes and ookinetes) in the midgut of mosquitoes fed with sugar solution supplemented with WaF17.12 (triangles), WaUM3 (squares) or sugar solution (dots) was evaluated at 24 h post-infection. Each symbol in the chart represent an individual midgut (n = 48 per group) and horizontal lines represent the medians (m) of two independent experiments (m = 710 for control group, m = 440 for WaUM3 group and m = 247 for WaF17.12 group). Statistical analysis was performed by multiple comparisons using the Mann–Whitney test (Control vs WaUM3: U(48) = 882.5, Z = 1.971, P = 0.04884; Control vs WaF17.12: U(48) = 486.5, Z = 4.87287, P < 0.0001; WaUM3 vs WaF17.12: U(48) = 684, Z = 3.42567, P = 0.0006). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001

Further analyses were then performed to evaluate possible inhibition effects of P. berghei (PbGFPCON) in the later stages of the sporogonic cycle. Specifically, guts and salivary glands of 10 mosquitoes for each group were analysed at 10 and 21 days post-infection, respectively. The number of oocysts and sporozoites was not significantly different in the three groups (data not shown). Nevertheless, the huge number of oocysts developing during experimental infections could have impaired the detection of anti-plasmodial effects in the later sporogonic stages.

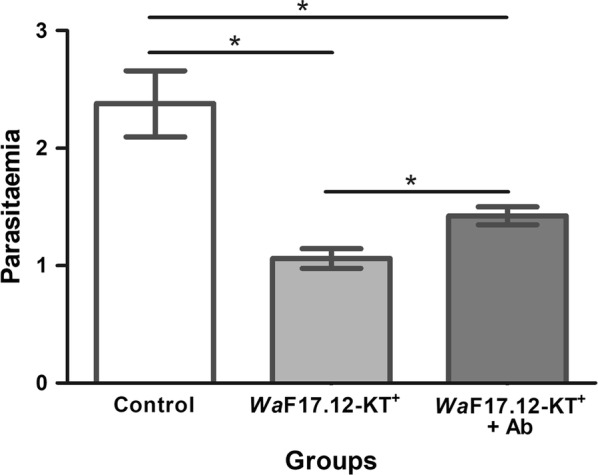

WaF17.12-KT+ anti-plasmodial activity against P. berghei PbGFPCON erythrocytic stages and preliminary safety tests

PbGFPCON infected donor mice were used to test the effects of WaF17.12-KT on erythrocytic stages. Infected blood samples were individually incubated for 90 min at 25 °C with WaF17.12-KT+ (100 µg/ml KT), or WaF17.12-KT+ (100 µg/ml KT) plus the specific anti-KT antibody mAbKT4 (100 µg/ml) [22], or PBS at 7.2 pH (control). The resulting mixtures were inoculated in healthy mice (n = 5 for each group), and parasitaemia was evaluated five days post-infection. The mean values ± SEM of two independent experiments are reported for each group (Fig. 3). A significant reduction in the parasitemia of both WaF17.12-KT+ (55.4%) and WaF17.12-KT+ plus Ab (40.1%) groups was detected indicating that WaF17.12-KT+ interferes with PbGFPCON erythrocytic stages and impairs the ability of the parasite to infect recipient mice. Interestingly, treatment with the monoclonal antibody mAbKT4 in part inhibited the effects of WaF17.12-KT+ showing a reduction percentage that is lower with respect to the KT group. It is reasonable that a saturating concentration of the antibody could cause a complete block of WaF17.12-KT activity.

Fig. 3.

WaF17.12-KT reduces parasitaemia in PbGFPCON infected mice. Healthy mice were inoculated using PbGFPCON-infected blood of a donor mouse previously incubated for 90 min at 25 °C with WaF17.12-KT+ (100 µg/ml KT), WaF17.12-KT+ (100 µg/ml KT) and mAbKT4, or PBS (control). Five days after inoculations, parasitaemia of the recipient mice (n = 5 per group) was evaluated and mean values ± SEM, calculated as reported in Bonkian et al. [34], are reported. The experiment was repeated twice. Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann–Whitney test (Control vs WaF17.12-KT+: U(10)v= 124, Z = 2.04228, P = 0.04136; Control vs WaF17.12-KT+ + Ab: U(10) = 83, Z = 1.790, P = 0.03673; WaF17.12-KT+ vs Ab: U(10) = 85, Z = 1.690, P = 0.03656). *P < 0.05

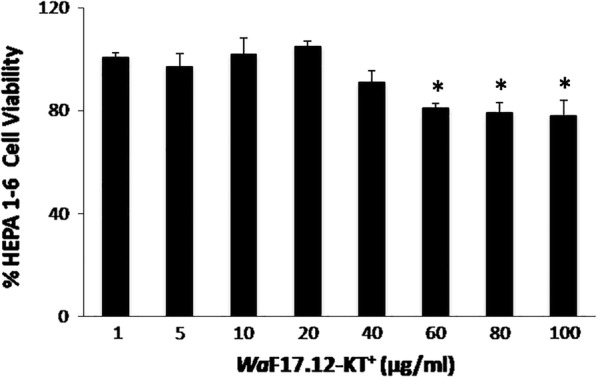

To evaluate the potential therapeutically use of WaF17.12-KT, a preliminary test was performed using the murine cell line HEPA 1–6. A viability assay was carried out through a colorimetric MTT test. Cells were incubated with different doses of WaF17.12-KT+ for 24 h (Fig. 4). Our data demonstrated that the treatment slightly affects cell viability only at the highest doses (60, 80 and 100 µg/ml KT), suggesting that KT can be considered safe on vertebrate cells. We carried out additional analysis using PI on HEPA 1–6 cells treated and not treated with KT, showing no cell damage at a dose of 100 μg/ml at 24 h of treatment (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

Fig. 4.

Safety test on murine cell line. HEPA 1–6 cells were cultured with different doses of WaFA17.12-KT+ for 24 h. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay. Data shown are expressed as mean ± SD of three separate experiments; *P < 0.01 vs vehicle-treated cells

Discussion

SC strategies propose the use of symbiotic microorganisms that interfere with the vector’s capability of blocking the transmission of malaria. In recent years, several bacteria and fungi have been indicated as good candidates for SC applications against malaria since they can inhibit the development of the parasite in wild mosquitoes. Direct or indirect anti-plasmodial mechanisms can be exerted by wild-type or recombinant microbial strains. In this context, the use of natural killer strains limits the introduction of genetically manipulated microorganisms into the environment. This aspect makes symbiotic strains of W. anomalus highly appealing for SC strategies, particularly after the discovery of their ability to produce KTs with anti-parasitic effects in the Anopheles midgut. In the present study, we demonstrated that a diet supplemented with activated WaF17.12 cultures inhibits the development of the early sporogonic stages of P. berghei in An. stephensi (− 65.21%). Interestingly, the KT non-producer strain WaUM3 also affected parasites (− 38.02%), likely by host immune system stimulation due to the massive presence of the yeast in the gut [28]. Nevertheless, the significantly higher effect of WaF17.12 highlighted a direct mechanism due to the action of KT. We have used only the KT non-producer strain WaUM3 as a negative control since a non-stimulated WaF17.12 control group is not obtainable. In fact, it is possible to induce higher or lower KT production by cultural methods using growth media at different pH values but not KT free cultures [20].

These outcomes are consistent with the demonstration that, in vitro, only WaF17.12 is able to prevent ookinete development (− 40%), supporting the hypothesis that the surface membrane damage is associated to WaF17.12-KT β-glucanase activity, as previously reported by Valzano et al. [19].

Although in vitro and in vivo inhibition rates cannot be compared because of substantial differences between the two experimental systems, we could speculate that the interaction of WaF17.12-KT with the parasite cell-wall carbohydrates may be more efficient in the midgut lumen.

We also investigated the development of later sporogonic stages in the mosquito fed with WaF17.12, finding that there is no antagonist effect on oocysts and sporozoites. In fact, Cappelli et al. [20] reported that WaF17.12-KT is released in the midgut lumen surrounding the epithelium, thus oocysts and sporozoites, differently from ookinetes, are not exposed to the toxin. Additionally, the 100-fold higher number of oocysts produced upon experimental infections with respect to natural conditions, could mask the anti-plasmodial effect of killer yeasts at the level of later sporogonic stages. In fact, the considered murine malaria system (P. berghei/An. stephensi/BALBc) is an experimental model optimized to have abundant infections in mosquitoes [29, 30]. To address this issue, additional tests using killer yeasts against human malaria parasites in naturally infected mosquitoes that develop no more than 5–10 oocysts [31], could be advisable. In fact, under these conditions WaF17.12-KT could break down the vector capacity. Interestingly, yeasts are already used in traps because the smell produced by their fermentation is able to attract mosquitoes [32]. Thus, sugary preparations supplemented with WaF17.12 cultures could be placed in traps to collect wild mosquitoes to be used for testing the anti-plasmodial effects on human malaria parasites. Further studies will assess symbiotic killer yeasts of anophelines as new candidates for innovative and safe SC-strategies of malaria.

The present study also provides evidence for the anti-plasmodial activity of WaF17.12-KT on erythrocytic stages, as shown by the KT-mediated reduction of parasitatemia observed in experimentally infected mice.

Interestingly, WaF17.12-KT was also active against parasite stages that develop in the vertebrate host, likely according to an antimicrobial mechanism of action based on glucanase activity. In fact, β-1,3-glucans are microbial cell wall components in charge of maintaining cell morphology and osmotic integrity [33]. Nevertheless, KT action could involve also different pathways, as a recent study reported the apoptotic activity of peptides mimicking KTs against the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii [34]. However, further investigations on human malaria parasites are requested to assess the mechanism of action of KTs.

Regardless of the mechanisms of action, tests against a murine cell line showed that WaF17.12-KT does not affect vertebrate cells.

Conclusions

Overall, these results demonstrate the anti-plasmodial activity of WaF17.12 on P. berghei sporogonic stages, showing that killer yeasts can potentially be used as safe and innovative tools against malaria. WaF17.12 could be applicable for symbiotic control in the field, taking advantage of the fact that killer yeasts are easily releasable in mosquito feeding sites. Furthermore, the effect of WaF17.12-KT against the erythrocytic stages suggest that yeast killer toxins can be used as novel antiparasitic drugs.

Additional file

Additional file 1: Figure S1. KT treatment does not induce cell damage. PI staining on HEPA 1–6 cells treated and not treated with KT (100 μg/ml) analysed by cytofluorimeter. Abbreviation: MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- Ab

antibody

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- KT

killer toxin

- IFA

immunofluorescence assay

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PI

propidium iodide

- SC

symbiotic control

- Wa

Wickerhamomyces anomalus

- YPD

yeast peptone dextrose

Authors’ contributions

IR conceived the study and contributed to it with data analysis, interpretation and manuscript writing. AC, MV, VC, PM and CA performed the experiments. JB contributed to the experiments and edited the English in the manuscript. AC, MV, PR and GF contributed to data interpretation and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union Horizon 2020 under Grant Agreement No. 842429 to IR.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its additional file.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Alessia Cappelli, Email: alessia.cappelli@unicam.it.

Matteo Valzano, Email: matteo.valzano@unicam.it.

Valentina Cecarini, Email: valentina.cecarini@unicam.it.

Jovana Bozic, Email: jovanabozic@ufl.edu.

Paolo Rossi, Email: paolo.rossi@unicam.it.

Priscilla Mensah, Email: priscilla.mensah@unicam.it.

Consuelo Amantini, Email: consuelo.amantini@unicam.it.

Guido Favia, Email: guido.favia@unicam.it.

Irene Ricci, Email: irene.ricci@unicam.it.

References

- 1.Moreira CK, Rodrigues FG, Ghosh A, Varotti Fde P, Miranda A, Daffre S, et al. Effect of the antimicrobial peptide gomesin against different life stages of Plasmodium spp. Exp Parasitol. 2007;116:346–353. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trape JF, Tall A, Diagne N, Ndiath O, Ly AB, Faye J, et al. Malaria morbidity and pyrethroid resistance after the introduction of insecticide-treated bednets and artemisinin-based combination therapies: a longitudinal study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:925–932. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang S, Jacobs-Lorena M. Genetic approaches to interfere with malaria transmission by vector mosquitoes. Trends Biotechnol. 2013;31:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Douglas AE. Symbiotic microorganisms: untapped resources for insect pest control. Trends Biotechnol. 2007;25:338–342. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ricci I, Valzano M, Ulissi U, Epis S, Cappelli A, Favia G. Symbiotic control of mosquito borne disease. Pathog Glob Health. 2012;106:380–385. doi: 10.1179/2047773212Y.0000000051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Favia G, Ricci I, Damiani C, Raddadi N, Crotti E, Marzorati M, et al. Bacteria of the genus Asaia stably associate with Anopheles stephensi, an Asian malarial mosquito vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:9047–9051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610451104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang S, Ghosh AK, Bongio N, Stebbings KA, Lampe DJ, Jacobs-Lorena M. Fighting malaria with engineered symbiotic bacteria from vector mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:12734–12739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204158109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang W, Vega-Rodríguez J, Ghosh AK, Jacobs-Lorena M, Kang A, St Leger RJ. Development of transgenic fungi that kill human malaria parasites in mosquitoes. Science. 2011;331:1074–1077. doi: 10.1126/science.1199115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steyn A, Roets F, Botha A. Yeasts associated with Culex pipiens and Culex theileri mosquito larvae and the effect of selected yeast strains on the ontogeny of Culex pipiens. Microb Ecol. 2016;71:747–760. doi: 10.1007/s00248-015-0709-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bozic J, Capone A, Pediconi D, Mensah P, Cappelli A, Valzano M, et al. Mosquitoes can harbour yeasts of clinical significance and contribute to their environmental dissemination. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2017;9:642–648. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ricci I, Mosca M, Valzano M, Damiani C, Scuppa P, Rossi P, et al. Different mosquito species host Wickerhamomyces anomalus (Pichia anomala): perspectives on vector-borne diseases symbiotic control. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2011;99:43–50. doi: 10.1007/s10482-010-9532-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker GM. Pichia anomala: cell physiology and biotechnology relative to other yeasts. Antoine Van Leeuwenhoek. 2011;99:25–34. doi: 10.1007/s10482-010-9491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sundh I, Melin P. Safety and regulation of yeasts intentionally added to the food or feed chains. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2010;99:113–119. doi: 10.1007/s10482-010-9528-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jijakli MH. Pichia anomala in biocontrol for apples: 20 years of fundamental research and practical applications. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2011;99:93–105. doi: 10.1007/s10482-010-9541-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olstorpe M, Schnürer J, Passoth V. Growth inhibition of various Enterobacteriaceae species by the yeast Hansenula anomala during storage of moist cereal grain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:292–294. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06024-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toki W, Tanahashi M, Togashi K, Fukatsu T. Fungal farming in a non-social beetle. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ricci I, Damiani C, Scuppa P, Mosca M, Crotti E, Rossi P, et al. The yeast Wickerhamomyces anomalus (Pichia anomala) inhabits the midgut and reproductive system of the Asian malaria vector Anopheles stephensi. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:911–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin E, Bongiorno G, Giovati L, Montagna M, Crotti E, Damiani C, et al. Isolation of a Wickerhamomyces anomalus yeast strain from the sandfly Phlebotomus perniciosus, displaying the killer phenotype. Med Vet Entomol. 2016;30:101–106. doi: 10.1111/mve.12149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valzano M, Cecarini V, Cappelli A, Capone A, Bozic J, Cuccioloni M, et al. A yeast strain associated to Anopheles mosquitoes produces a toxin able to kill malaria parasites. Malar J. 2016;15:21. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-1059-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cappelli A, Ulissi U, Valzano M, Damiani C, Epis S, Gabrielli MG, et al. A Wickerhamomyces anomalus killer strain in the malaria vector Anopheles stephensi. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gill DE. Intrinsic rate of increase, saturation density and competitive ability. II. The evolution of competitive ability. Am Nat. 1974;108:103–116. doi: 10.1086/282888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polonelli L, Séguy N, Conti S, Gerloni M, Bertolotti D, Cantelli C, et al. Monoclonal yeast killer toxin-like candidacidal anti-idiotypic antibodies. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:142–146. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.2.142-146.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guyard C, Séguy N, Cailliez JC, Drobecq H, Polonelli L, Dei-Cas E, et al. Characterization of a Williopsis saturnus var. mrakii high molecular weight secreted killer toxin with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;49:961–971. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vlachou D, Zimmermann T, Cantera R, Janse CJ, Waters AP, Kafatos FC. Real-time, in vivo analysis of malaria ookinete locomotion and mosquito midgut invasion. Cell Micro. 2004;6:671–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orjuela-Sánchez P, Duggan E, Nolan J, Frangos JA, Carvalho LJ. A lactate dehydrogenase ELISA-based assay for the in vitro determination of Plasmodium berghei sensitivity to anti-malarial drugs. Malar J. 2012;11:366. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clayton AM, Dong Y, Dimopoulos G. The Anopheles innate immune system in the defence against malaria infection. Innate Immun. 2014;6:169–181. doi: 10.1159/000353602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonkian LN, Yerbanga RS, Koama B, Soma A, Cisse M, Valea I, et al. In vivo antiplasmodial activity of two Sahelian plant extracts on Plasmodium berghei ANKA infected NMRI mice. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018;24:6859632. doi: 10.1155/2018/6859632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemaitre B, Nicolas E, Michaut L, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA. The dorsoventral regulatory gene cassette spätzle/Toll/cactus controls the potent antifungal response in Drosophila adults. Cell. 1996;86:973–983. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinden RE. Infection of mosquitoes with rodent malaria. In: Crampton JM, Beard CB, Louis C, editors. Molecular biology of insect disease vectors: a methods manual. London: Chapman and Hall; 1997. pp. 67–91. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodman AL, Forbes EK, Williams AR, Douglas AD, de Cassan SC, Bauza K, et al. The utility of Plasmodium berghei as a rodent model for anti-merozoite malaria vaccine assessment. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1706. doi: 10.1038/srep01706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abraham EG, Jacobs-Lorena M. Mosquito midgut barriers to malaria parasite development. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:667–671. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.St Laurent B, Oy K, Miller B, Gasteiger EB, Lee E, Sovannaroth S, et al. Cow-baited tents are highly effective in sampling diverse Anopheles malaria vectors in Cambodia. Malar J. 2016;15:440. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1488-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magliani W, Conti S, Giovati L, Maffei DL, Polonelli L. Anti-beta-glucan-likeimmunoprotectivecandidacidalantiidiotypicantibodies. Front Biosci. 2008;13:6920–6937. doi: 10.2741/3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giovati L, Santinoli C, Mangia C, Vismarra A, Belletti S, D’adda T, et al. Novel activity of a synthetic decapeptide against Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:753. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. KT treatment does not induce cell damage. PI staining on HEPA 1–6 cells treated and not treated with KT (100 μg/ml) analysed by cytofluorimeter. Abbreviation: MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its additional file.