Abstract

Objective

Routine screening for Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) infections in sexually exposed anatomical sites may be challenging in resource-limited settings. The objective of this study was to determine the proportion of missed CT/NG diagnoses if a single anatomical site screening was performed among men who have sex with men (MSM) by examining the pattern of anatomical sites of CT/NG infections.

Methods

Thai MSM were enrolled to the community-led test and treat cohort. Screening for CT/NG infections was performed from pharyngeal swab, rectal swab and urine using nucleic acid amplification testing. The correlations of CT/NG among the three anatomical sites were analysed.

Results

Among 1610 MSM included in the analysis, 21.7% had CT and 15.5% had NG infection at any anatomical site. Among those tested negative for CT or NG infection at either pharyngeal, rectal or urethral site, 8%–19% had CT infection and 7%–12% had NG infection at the remaining two sites. Of the total 349 CT infections, 85.9%, 30.6% and 67.8% would have been missed if only pharyngeal, rectal or urethral screening was performed, respectively. Of the total 249 NG infection, 55.7%, 39.6% and 77.4% would have been missed if only pharyngeal, rectal or urethral screening was performed, respectively. The majority of each anatomical site of CT/NG infection was isolated to their respective site, with rectal site having the highest proportion of isolation: 78.9% of rectal CT and 62.7% of rectal NG infection.

Conclusions

A high proportion of CT/NG infections would be missed if single anatomical site screening was performed among MSM. All-site screening is highly recommended, but if not feasible, rectal screening provides the highest yield of CT/NG diagnoses. Effort in lowering the cost of the CT/NG screening test or developing affordable molecular technologies for CT/NG detection is needed for MSM in resource-limited settings.

Trial Registration Number

NCT03580512; Results.

Keywords: men who have sex with men, chlamydia trachomatis, neisseria gonorrhoeae

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study includes a large number of sexually active men who have sex with men (MSM) who completed Chlamydia trachomatis (CT)/Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) screening in all three anatomical sites based on their self-reported sexually exposed contact routes.

Correlations of CT/NG infections among pharyngeal, rectal and urethral sites among sexually active MSM were identified, and showed the proportion of missed diagnoses if single anatomical site screening was performed.

Because CT/NG screening in our study was based on self-reported sexually exposed contact routes, we were unable to compare the performance between a history-based and universal approach.

Extragenitalia samples from a modest number of participants may have been missed due to social desirability bias regarding questions about the site(s) of sexual contact.

Introduction

Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) infections are among the most common bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and disproportionately affect men who have sex with men (MSM) worldwide.1 Two large studies conducted in Thailand between 2006 and 2010 showed that MSM had approximately 30% higher prevalence of CT infection and up to five times higher prevalence of NG infection compared with men who have sex exclusively with women.2 3

CT/NG infections are associated with acquiring and transmitting HIV infection.4 In particular, rectal CT/NG infection is strongly associated with an increased risk of HIV acquisition among MSM.5 6 And while the impact of pharyngeal infection towards HIV acquisition is less understood, it is highly prevalent and may, therefore, serve as an important for infection at genital sites.7–9 Since CT/NG infections are often asymptomatic,10 the lack of routine screening may result in a missed opportunity to diagnosis these curable STIs.

The diagnosis of CT/NG infections, both at genital and extragenital sites, can be made using nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs). Many studies have shown superior sensitivity and specificity of NAATs in detecting extragenital CT/NG infection compared with culture.11–14 The findings prompted the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to recommend the use of NAATs for pharyngeal and rectal CT/NG screening,15 although they have not been cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration.

Frequency of testing and anatomical sites to be tested are the two factors to consider in asymptomatic CT/NG screening. The CDC STD treatment guideline recommends that all sexually active MSM should be screened at least annually at sites of contact regardless of condom use.15 More frequent screening is advised if the individuals are at increased risk. Conversely, the Australian STI management guideline recommends screening at all sites regardless of sexually exposed contact routes.16 However, many barriers prevent the implementation of these recommendations in clinical practice. For the clients, these barriers may include the cost of tests, underestimating the risk of asymptomatic infections and concern of being stigmatised.17 18 Healthcare providers also often lack knowledge on the importance of STI screening at appropriate anatomical sites,17 which may also be the case in Thailand where there are currently no consensus recommendations for CT/NG screening.

Our primary objective was to determine the proportion of missed CT/NG diagnoses if a single anatomical site screening was performed among MSM by examining the pattern of anatomical sites of CT/NG infections. Other objectives were to determine the prevalence of CT/NG infections among MSM enrolled in the community-led test and treat cohort and to examine the prevalence of CT/NG infections in the remaining two anatomical sites if one site was negative to evaluate the proportion of missed diagnoses per individual. The findings from our study will be crucial in guiding the recommendations for CT/NG screening among MSM, both in HIV treatment and prevention programmes, in resource-limited settings.

Methods

Enrolment of participants

The present study used data from MSM participants enrolled in the community-led test and treat cohort between October 2015 and October 2016. The community-led test and treat cohort aimed to evaluate the feasibility of empowering lay providers who are members of MSM and transgender women (TGW) communities to provide HIV-related services, increasing uptake of HIV testing and treatment services among MSM and TGW in Thailand.

Eligible criteria and study procedures for the community-led test and treat cohort have been reported in detail elsewhere.19 In brief, adults Thai MSM and TGW with a history of at least one unprotected anal sexual intercourse with a man in the past 6 months were enrolled from Service Workers IN Group drop-in centres (DICs) in Bangkok and Pattaya city, Rainbow Sky Association of Thailand DICs in Bangkok and Songkhla, Caremat DIC in Chiang Mai and Sisters DIC in Pattaya city, Thailand for an 18-month follow-up period. Only participants of unknown HIV status were enrolled, and those with known HIV infection were excluded from enrolment. Screening for CT and NG was performed at enrolment using NAAT (Abbott Real Time CT/NG, Abbott Molecular, Illinois, USA) from pharyngeal swab, rectal swab and/or urine collection based on the self-report sexually exposed contact routes. Participants who completed both CT and NG screening in all three anatomical sites at baseline were included in this analysis.

All participants gave informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA). Demographic, CT/NG and HIV testing results, and sexual risk behaviours were summarised as median (IQR) and number (percentage) for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Characteristics between HIV-positive and HIV-negative participants were compared using a χ2 or Fisher’s exact test, or Mann-Whitney test as appropriate.

The distribution of anatomical sites of CT/NG infections at baseline was analysed to determine the proportion (prevalence with 95% CI) of missed CT/NG diagnoses per individual if single anatomical site screening was performed, pattern of anatomical distribution for all CT/NG infections and pattern of anatomical distribution of CT/NG infections by anatomical site. Statistical significance was defined as p value of <0.05.

Participant and public involvement

Neither participants nor public were directly involved in the development, design or recruitment of the study.

Results

Participant characteristics

Of 1858 MSM enrolled in the community-led test and treat cohort, a total of 1610 (86.7%) participants completed both CT and NG testing in all three anatomical sites at baseline based on their self-reported sexually exposed contact routes and were included in the analysis. Compared with MSM who did not complete CT/NG testing in all three anatomical sites, MSM who completed CT/NG testing in all three anatomical sites had higher prevalence of CT/NG infections at any anatomical sites (29.9% vs 16.4%, p<0.001) and reported higher sexual risk behaviours (online supplementary file 1).

bmjopen-2018-028162supp001.pdf (224.2KB, pdf)

At enrolment, the prevalence of CT/NG infections at any anatomical sites was 29.9%: 21.7% for CT infection and 15.5% for NG infection. The most prevalent CT/NG infections by anatomical sites were rectal CT (15.0%), rectal NG (9.3%) and urethral CT (7.0%). HIV-positive participants had significantly higher prevalence of both CT and NG infections in all anatomical sites, except for pharyngeal NG, and were more likely than HIV-negative participants to be enrolled from the Bangkok sites, self-perceived high risk of HIV transmission in the past month, had unprotected sex in the past month and self-reported or unsure of having STIs in the past month (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic of 1610 men who have sex with men included in the analysis

| Characteristics | Overall (n=1610) |

HIV positive (n=303) |

HIV negative (n=1307) |

P value | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Median age (IQR) years | 24.1 (20.8–30.0) |

24.1 (21.0–28.7) |

24.1 (20.8–30.5) |

0.48 | |||

| Site | <0.001 | ||||||

| Bangkok | 676 | 42.0 | 164 | 54.1 | 512 | 39.2 | |

| Chiang Mai | 541 | 33.6 | 61 | 20.1 | 480 | 36.7 | |

| Hat Yai | 152 | 9.4 | 17 | 5.6 | 135 | 10.3 | |

| Pattaya city | 241 | 15.0 | 61 | 20.1 | 180 | 13.8 | |

| Marital status | 0.19 | ||||||

| Single | 1158/1598 | 72.5 | 218/301 | 72.4 | 940/1297 | 72.5 | |

| Living together with male partner | 381/1598 | 23.8 | 77/301 | 25.6 | 304/1297 | 23.4 | |

| Married to a woman | 59/1598 | 3.7 | 6/301 | 2.0 | 53/1297 | 4.1 | |

| Highest education | 0.46 | ||||||

| Lower than high school | 325/1594 | 20.4 | 68/299 | 22.7 | 257/1295 | 19.9 | |

| High school | 638/1594 | 40.0 | 120/299 | 40.1 | 518/1295 | 40.0 | |

| Higher than high school | 631/1594 | 39.6 | 111/299 | 27.1 | 520/1295 | 40.2 | |

| Main occupation | 0.06 | ||||||

| Unemployed | 97/1598 | 6.1 | 25/300 | 8.3 | 72/1298 | 5.6 | |

| Student | 486/1598 | 30.4 | 76/300 | 25.3 | 410/1298 | 31.6 | |

| Sex worker | 707/1598 | 44.2 | 133/300 | 44.3 | 574/1298 | 44.2 | |

| Employed, other than sex worker | 308/1598 | 19.3 | 66/300 | 22.0 | 242/1298 | 18.6 | |

| Income>10 000 THB (US$320) per month | 672/1383 | 48.6 | 124/264 | 47.0 | 548/1119 | 49.0 | 0.56 |

| Median age (IQR) of first sexual intercourse | 17 (15–19) |

17 (15–19) |

17 (15–19) |

0.22 | |||

| Male circumcision | 186/1391 | 13.4 | 25/240 | 10.4 | 161/1151 | 14.0 | 0.14 |

| Number of sexual partners in the past 6 months | 0.34 | ||||||

| No sexual partner | 30/1603 | 1.9 | 7/300 | 2.3 | 23/1303 | 1.8 | |

| Single partner | 308/1603 | 19.2 | 59/300 | 19.7 | 249/1303 | 19.1 | |

| Multiple partners | 870/1603 | 54.3 | 150/300 | 50.0 | 720/1303 | 55.3 | |

| Refuse to answer | 395/1603 | 24.6 | 84/300 | 28.0 | 311/1303 | 23.9 | |

| Unprotected sex in the past 6 months | 1261/1586 | 79.5 | 252/298 | 84.6 | 1009/1288 | 78.3 | 0.02 |

| Illicit drug used in the past 6 months | 599/1530 | 39.2 | 100/278 | 36.0 | 499/1252 | 39.9 | 0.23 |

| Self-reported STIs in the past 6 months | <0.001 | ||||||

| No | 977/1546 | 63.2 | 146/291 | 50.2 | 831/1255 | 66.2 | |

| Yes | 106/1546 | 6.9 | 21/291 | 7.2 | 85/1255 | 6.8 | |

| Not sure | 463/1546 | 29.9 | 124/291 | 42.6 | 339/1255 | 27.0 | |

| Group sex in the past 6 months | 207/1520 | 13.6 | 47/286 | 16.4 | 160/1234 | 13.0 | 0.12 |

| Overall CT infections | 349 | 21.7 | 111 | 36.6 | 238 | 18.2 | <0.001 |

| Pharyngeal CT | 48 | 3.0 | 17 | 5.6 | 31 | 2.4 | 0.003 |

| Rectal CT | 242 | 15.0 | 88 | 29.0 | 154 | 11.8 | <0.001 |

| Urethral CT | 112 | 7.0 | 29 | 9.6 | 83 | 6.4 | 0.04 |

| Overall NG infections | 249 | 15.5 | 91 | 30.0 | 158 | 12.1 | <0.001 |

| Pharyngeal NG | 110 | 6.8 | 25 | 8.3 | 85 | 6.5 | 0.28 |

| Rectal NG | 150 | 9.3 | 68 | 22.4 | 82 | 6.3 | <0.001 |

| Urethral NG | 56 | 3.5 | 22 | 7.3 | 34 | 2.6 | <0.001 |

CT, Chlamydia trachomatis; NG, Neisseria gonorrhoeae; STIs, sexually transmitted infections; THB, Thai baht.

The proportion of missed CT/NG diagnoses per individual if single anatomical site screening was performed

Among participants who tested negative for CT infection at pharyngeal, rectal or urethral sites, 19.3%, 7.8% or 15.8% had CT infection in any of the remaining two sites, respectively (table 2). HIV-positive MSM had significantly higher prevalence of CT infection in any of the remaining two sites among those who tested negative for pharyngeal (32.9% vs 16.2%, p<0.001) or urethral CT (29.9% vs 12.7%, p<0.001) compared with HIV-negative MSM. Among those who tested negative for NG infection at pharyngeal, rectal or urethral site, 9.3%, 6.8% or 12.4% had NG infection in any of the remaining two sites, respectively (table 3). HIV-positive MSM had significantly higher prevalence of NG infection in any of the remaining two sites across all anatomical sites tested negative (23.7% vs 6.0%, p<0.001 among those who tested negative for pharyngeal NG; 9.6% vs 6.2%, p=0.045 among those who tested negative for rectal NG; and 24.6% vs 9.7%, p<0.001 among those who tested negative for urethral NG).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis infections at the remaining two sites among men who have sex with men who had negative result at pharyngeal, rectal and urethral sites, respectively

| Negative site | Positive site | Prevalence (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Overall | HIV positive | HIV negative | |||

| Pharyngeal (n=1562) |

Rectal (n=223) | 14.3 (12.6 to 16.1) | 27.6 (22.5 to 33.2) | 11.3 (9.6 to 13.2) | <0.001 |

| Urethral (n=110) | 7.0 (5.8 to 8.4) | 10.1 (6.9 to 14.2) | 6.4 (5.1 to 7.8) | 0.02 | |

| Rectal or urethral (n=301) | 19.3 (17.3 to 21.3) | 32.9 (27.5 to 38.6) | 16.2 (14.2 to 18.4) | <0.001 | |

| Rectal (n=1368) |

Pharyngeal (n=29) | 2.1 (1.4 to 3.0) | 3.7 (1.6 to 7.2) | 1.8 (1.1 to 2.8) | 0.08 |

| Urethral (n=79) | 5.8 (4.6 to 7.2) | 7.0 (4.0 to 11.2) | 5.6 (4.3 to 7.0) | 0.41 | |

| Pharyngeal or urethral (n=107) | 7.8 (6.5 to 9.4) | 10.7 (6.9 to 15.6) | 7.3 (5.9 to 8.9) | 0.09 | |

| Urethral (n=1498) |

Pharyngeal (n=46) | 3.1 (2.3 to 4.1) | 6.2 (3.7 to 9.7) | 2.4 (1.6 to 3.4) | 0.001 |

| Rectal (n=209) | 14.0 (12.2 to 15.8) | 27.0 (21.8 to 32.7) | 11.0 (9.3 to 12.9) | <0.001 | |

| Pharyngeal or rectal (n=237) | 15.8 (14.0 to 17.8) | 29.9 (24.6 to 35.7) | 12.7 (10.9 to 14.7) | <0.001 | |

Table 3.

Prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections at the remaining two sites among men who have sex with men who had negative result at pharyngeal, rectal and urethral sites, respectively

| Negative site | Positive site | Prevalence (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Overall | HIV positive | HIV negative | |||

| Pharyngeal (n=1500) |

Rectal (n=108) | 7.2 (5.9 to 8.6) | 20.5 (15.9 to 25.7) | 4.2 (3.1 to 5.5) | <0.001 |

| Urethral (n=45) | 3.0 (2.2 to 4.0) | 6.1 (3.6 to 9.6) | 2.3 (1.5 to 3.3) | 0.001 | |

| Rectal or urethral (n=139) | 9.3 (7.8 to 10.8) | 23.7 (18.9 to 29.2) | 6.0 (4.7 to 7.5) | <0.001 | |

| Rectal (n=1460) |

Pharyngeal (n=68) | 4.7 (3.6 to 5.9) | 6.0 (3.3 to 9.8) | 4.4 (3.3 to 5.7) | 0.30 |

| Urethral (n=36) | 2.5 (1.7 to 3.4) | 4.3 (2.1 to 7.7) | 2.1 (1.4 to 3.1) | 0.05 | |

| Pharyngeal or urethral (n=99) | 6.8 (5.5 to 8.2) | 9.8 (6.3 to 14.3) | 6.2 (4.9 to 7.7) | 0.045 | |

| Urethral (n=1554) |

Pharyngeal (n=99) | 6.4 (5.2 to 7.7) | 7.1 (4.4 to 10.8) | 6.2 (4.9 to 7.7) | 0.57 |

| Rectal (n=130) | 8.4 (7.0 to 9.9) | 19.9 (15.4 to 25.1) | 5.8 (4.6 to 7.2) | <0.001 | |

| Pharyngeal or rectal (n=193) | 12.4 (10.8 to 14.2) | 24.6 (19.6 to 30.0) | 9.7 (8.2 to 11.5) | <0.001 | |

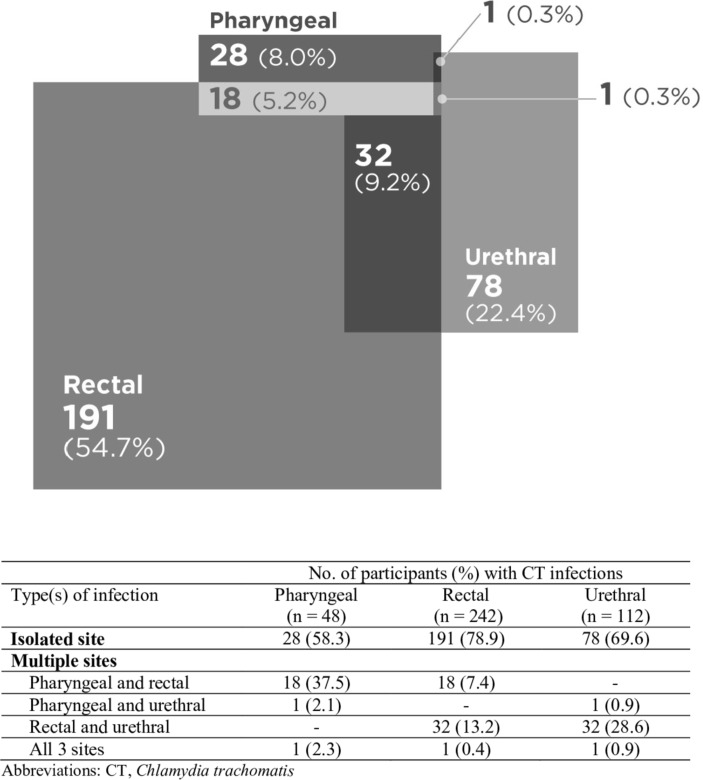

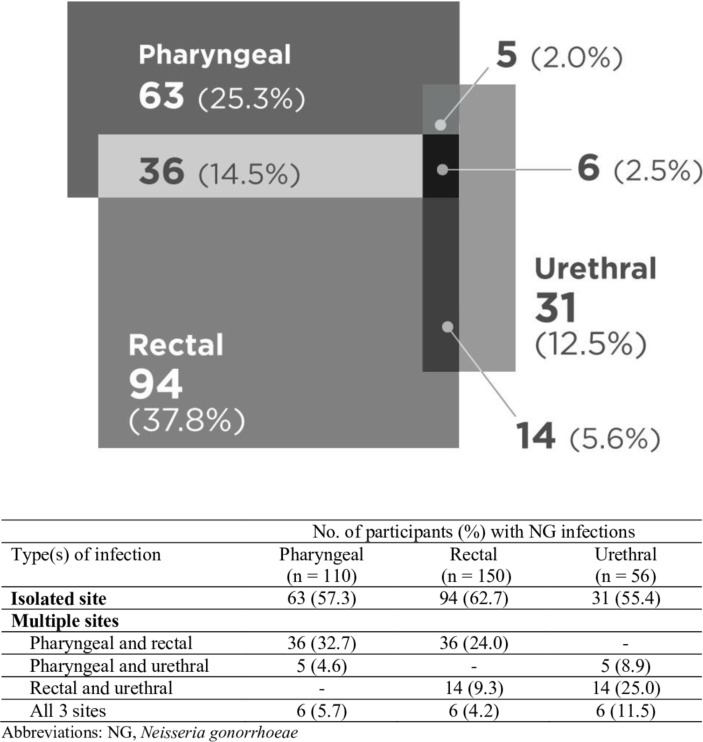

Pattern of anatomical distribution for all CT/NG infections

Of the total 349 CT infections in our study, 8.0% were isolated to pharyngeal site, 54.7% to rectal site and 22.4% to urethral site (figure 1). On the basis of our data, 85.9%, 30.6% and 67.8% of the total CT infections in our study would have been missed if only pharyngeal, rectal or urethral screening was performed, respectively. Of the total 249 NG infections, 25.3%, 37.8% and 12.5% were isolated to pharyngeal, rectal and urethral sites, respectively (figure 2). Collectively, 55.7%, 39.6% and 77.4% of NG infections would have been missed if only pharyngeal, rectal or urethral screening was performed, respectively.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) infections (n=349) by anatomical site.

Figure 2.

Distribution of Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) infections (n=249) by anatomical site.

Pattern of anatomical distribution of CT/NG infections by anatomical site

Rectal site was the most isolated site of CT/NG infection: 191 out of 242 (78.9%) rectal CT infection and 94 out of 150 rectal NG infection were isolated to rectum (figures 1 and 2). Importantly, the majority of each anatomical site of CT/NG infection was isolated to their respective site: 58.3% and 57.3% for pharyngeal CT and NG infection, respectively, and 69.6% and 55.4% for urethral CT and NG infection, respectively.

Discussion

We examined the pattern of anatomical sites of CT/NG infections and showed that among MSM who tested negative for CT or NG infection at either pharyngeal, rectal or urethral site, 8%–19% had CT infection and 7%–12% had NG infection at the remaining two sites. Of the 349 CT infections, 8.0% were isolated to pharyngeal site, 54.7% to rectal site and 22.4% to urethral site; and 85.9%, 30.6% and 67.8% of the total CT infections would have been missed if only pharyngeal, rectal or urethral screening was performed, respectively. Of the 249 NG infections, 25.3%, 37.8% and 12.5% were isolated to pharyngeal, rectal and urethral sites, respectively; and 55.7%, 39.6% and 77.4% of NG infections would have been missed if only pharyngeal, rectal or urethral screening was performed, respectively. The majority of each anatomical site of CT/NG infection was isolated to their respective site, with rectal site having the highest proportion of isolation: 78.9% of rectal CT and 62.7% of rectal NG infection. These data suggest that screening at all self-report sexually exposed contact routes is highly recommended. However, if this is not feasible, screening at rectal site would provide the highest yield of CT/NG diagnoses.

The overall prevalence CT/NG infections at any anatomical sites in our cohort was comparable to the historical Thai facility-based test and treat cohort which enrolled previously unknown HIV-status Thai adult MSM and TGW with similar risk behaviours in 2012 (21.4% for CT and 12.4% for NG infection).20 The prevalence of CT/NG infections per each anatomical site in our study was comparable to one of the largest studies tested for pharyngeal, rectal and urethral CT/NG infections based on their self-reported exposure conducted in San Francisco between 2010 and 2011. Among 3039 MSM enrolled, the prevalence of pharyngeal, rectal and urethral CT infections was 2.3%, 11.9% and 4.4%, respectively; and 6.5%, 9.7%, and 5.5% for pharyngeal, rectal and urethral NG infections, respectively.21

To the best of our knowledge, our study was among the first to report the proportion of missed CT/NG diagnoses per individual if single anatomical site screening was performed. Supposing that one anatomical site screening was performed, 8%–19% of MSM who tested negative for CT infection and 7%–12% of those tested negative for NG infection actually had CT and NG infections at the remaining two anatomical sites, respectively. Importantly, the proportion of these potential missed CT/NG diagnoses increased to 11%–33% for CT and 10%–25% for NG infection among newly diagnosed HIV-positive MSM. This may be because of a higher proportion of unprotected sex and self-reported STIs in the past 6 months among HIV-positive MSM compared with HIV-negative MSM. These results point out the importance of CT/NG screening at all self-report sexually exposed contact routes. However, if resource limits the number of sites screened, rectal site proves to be the site of choice for screening, with less than 10% showed any infection in the remaining two anatomical sites if tested negative.

A study conducted in San Francisco in 2003, in which NAATs were used to test MSM for chlamydia and gonorrhoea at all three anatomical sites, was among the first published studies to show that the majority of CT (53%) and NG (64%) infections were at non-urethral sites, and would have been missed if only urethral screening was performed.10 More recent published data from multisite in USA and the Netherlands showed a range of 43%–69% of extragenital CT infection and 46%–76% of extragenital NG infection would have been missed if only urethral screening was performed, which were in line to our findings.21–24 Data from the San Francisco’s STD clinic between 2008 and 2009 showed that if one anatomical site screening was performed, screening only the pharynx would miss 81% of CT infection and 32% of NG infection; and screening only the rectum would miss 23% of CT infection and 52% of NG infection.25 Regardless of our similar findings that rectal site screening would miss the fewest infections, the high proportion of potential missed diagnoses if a single anatomical site screening was performed in any of the three sites supports the critical need for all sites, at least depending on self-reported sexually exposed contact routes, among MSM.

Although CT/NG infections at each anatomical site possess distinct characteristics, such as clinical manifestations, different duration of infections, and concerns over drug-resistant pathogens,26 27 the most important thing is the ability to detect and treat those infections regardless of site. Due to their asymptomatic nature, many patients may not be aware of the importance of the infections and do not seek medical advice.18 Healthcare provider can take the lead in encouraging sexually active MSM to screen for CT/NG infections, at least depending on their self-reported site of exposure, as the first step towards detecting and providing timely screening and treatment towards preventing transmission in the community.

Nonetheless, the cost of the test could be a major obstacle in implementing this recommendation resource-limited settings. For instance, the current cost of NAAT test for CT/NG infections in Thailand is approximately US$30 per anatomical site. This is considered expensive since more than half of our MSM participants have monthly income of less than US$320. To reduce the cost of test, a strategy to test pooled specimen has been made with promising results.28 Effort in lowering the cost of the CT/NG screening test or developing affordable molecular technologies for CT/NG detection is needed for MSM in resource-limited settings.

Certain limitations need to be considered. First, sexual behaviours were assessed using a self-administered paper questionnaire. While self-administered questionnaires may improve disclosure of sensitive behaviours, actual risk behaviours may still be under-reported. Second, risk behaviours were captured within the past 6 months. Because CT and NG infections have a long duration of infection, capturing risk behaviours within the past 6 months was beneficial in assessing risk behaviours since the potential contact date of the infections. However, the relatively long recall period may lead to recall bias. Third, because CT/NG screening in our study was based on self-reported sexually exposed contact routes rather than universal screening at all sites, we were unable to compare the performance between a history-based and universal approach. Furthermore, by limiting our analysis to MSM who self-reported sexual contact in all three anatomical sites, the findings may be biased towards those with higher risks which may have led to an overestimation of prevalence of CT/NG infections in our sample. Finally, we may have missed extragenitalia samples from a modest number of participants (248 MSM (13.4% of total MSM enrolled)) due to social desirability bias regarding questions about the site(s) of sexual contact.

Our study found that a high proportion of CT/NG infections would have been missed among MSM if single anatomical site screening is performed, especially among HIV-positive MSM. We recommend that all-site screening should be performed among MSM, at least based on self-reported sexually exposed contact routes. However, if this is not feasible, rectal screening provides the highest yield of CT/NG diagnoses. Effort in lowering the cost of the CT/NG screening test or developing affordable molecular technologies for CT/NG detection is needed for MSM in resource-limited settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere thanks to all participants and study staff. This work was made possible by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). The contents are the responsibility of the LINKAGES project and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, PEPFAR or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Contributors: AH interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript and performed statistical analysis. TS and JJ coordinated the study and oversaw data management. DT gave advised on statistical analysis and performed statistical analysis. TS, JJ, SM, RV and NP designed and conducted the study. NP advised on the analysis plan. NP and PP led the study. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final draft of manuscript.

Funding: Funding for this project was supported through LINKAGES, a five-year cooperative agreement (AID-OAA-A-14-00045), which is led by FHI 360 in partnership with IntraHealth International, Pact, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study (NCT03580512) was approved by the institutional review boards of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (IRB No. 181/57), the Department of Disease Control, Thai Ministry of Public Health (IRB No. 9/57-678), the Provincial Health Offices of Chonburi (IRB No. 0032.003/658), Songkhla (IRB No. 075/2014), and Chiang Mai (IRB No. 0032.002/35859).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available. Please contact corresponding author.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually trasmitted disease surveillance 2017, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tongtoyai J, Todd CS, Chonwattana W, et al. Prevalence and correlates of chlamydia trachomatis and neisseria gonorrhoeae by anatomic site among urban thai men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2015;42:440–9. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jatapai A, Sirivongrangson P, Lokpichat S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for Chlamydia trachomatis infection among young Thai men in 2008-2009. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:241–6. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31827e8de4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect 1999;75:3–17. 10.1136/sti.75.1.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bernstein KT, Marcus JL, Nieri G, et al. Rectal gonorrhea and chlamydia reinfection is associated with increased risk of HIV seroconversion. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;53:537–43. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c3ef29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Katz DA, Dombrowski JC, Bell TR, et al. HIV incidence among men who have sex with men after diagnosis with sexually transmitted infections. Sex Transm Dis 2016;43:249–54. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lutz AR. Screening for asymptomatic extragenital gonorrhea and chlamydia in men who have sex with men: significance, recommendations, and options for overcoming barriers to testing. LGBT Health 2015;2:27–34. 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morris SR, Klausner JD, Buchbinder SP, et al. Prevalence and incidence of pharyngeal gonorrhea in a longitudinal sample of men who have sex with men: the EXPLORE study. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:1284–9. 10.1086/508460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weinstock H, Workowski KA. Pharyngeal gonorrhea: an important reservoir of infection? Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:1798–800. 10.1086/648428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kent CK, Chaw JK, Wong W, et al. Prevalence of rectal, urethral, and pharyngeal chlamydia and gonorrhea detected in 2 clinical settings among men who have sex with men: San Francisco, California, 2003. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:67–74. 10.1086/430704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bachmann LH, Johnson RE, Cheng H, et al. Nucleic acid amplification tests for diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis rectal infections. J Clin Microbiol 2010;48:1827–32. 10.1128/JCM.02398-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bachmann LH, Johnson RE, Cheng H, et al. Nucleic acid amplification tests for diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae oropharyngeal infections. J Clin Microbiol 2009;47:902–7. 10.1128/JCM.01581-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mimiaga MJ, Mayer KH, Reisner SL, et al. Asymptomatic gonorrhea and chlamydial infections detected by nucleic acid amplification tests among Boston area men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2008;35:495–8. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31816471ae [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schachter J, Moncada J, Liska S, et al. Nucleic acid amplification tests in the diagnosis of chlamydial and gonococcal infections of the oropharynx and rectum in men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2008;35:637–42. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31817bdd7e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep 2015;64:1–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ooi C, Lewis D. Updating the management of sexually transmitted infections. Aust Prescr 2015;38:204–8. 10.18773/austprescr.2015.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barbee LA, Dhanireddy S, Tat SA, et al. Barriers to Bacterial Sexually Transmitted Infection Testing of HIV-Infected Men Who Have Sex With Men Engaged in HIV Primary Care. Sex Transm Dis 2015;42:590–4. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Denison HJ, Bromhead C, Grainger R, et al. Barriers to sexually transmitted infection testing in New Zealand: a qualitative study. Aust N Z J Public Health 2017;41:432–7. 10.1111/1753-6405.12680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Seekaew P, Pengnonyang S, Jantarapakde J, et al. Characteristics and HIV epidemiologic profiles of men who have sex with men and transgender women in key population-led test and treat cohorts in Thailand. PLoS One 2018;13:e0203294 10.1371/journal.pone.0203294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hiransuthikul A, Pattanachaiwit S, Teeratakulpisarn N, et al. High subsequent and recurrent sexually transmitted infection prevalence among newly diagnosed HIV-positive Thai men who have sex with men and transgender women in the Test and Treat cohort. Int J STD AIDS 2019;30:956462418799213 10.1177/0956462418799213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barbee LA, Dombrowski JC, Kerani R, et al. Effect of nucleic acid amplification testing on detection of extragenital gonorrhea and chlamydial infections in men who have sex with men sexually transmitted disease clinic patients. Sex Transm Dis 2014;41:168–72. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gunn RA, O’Brien CJ, Lee MA, et al. Gonorrhea screening among men who have sex with men: value of multiple anatomic site testing, San Diego, California, 1997-2003. Sex Transm Dis 2008;35:845–8. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318177ec70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koedijk FD, van Bergen JE, Dukers-Muijrers NH, et al. The value of testing multiple anatomic sites for gonorrhoea and chlamydia in sexually transmitted infection centres in the Netherlands, 2006-2010. Int J STD AIDS 2012;23:626–31. 10.1258/ijsa.2012.011378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van Liere GA, Hoebe CJ, Dukers-Muijrers NH. Evaluation of the anatomical site distribution of chlamydia and gonorrhoea in men who have sex with men and in high-risk women by routine testing: cross-sectional study revealing missed opportunities for treatment strategies. Sex Transm Infect 2014;90:58–60. 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marcus JL, Bernstein KT, Kohn RP, et al. Infections missed by urethral-only screening for chlamydia or gonorrhea detection among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2011;38:922–4. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31822a2b2e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chow EP, Camilleri S, Ward C, et al. Duration of gonorrhoea and chlamydia infection at the pharynx and rectum among men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Sex Health 2016;13:199–204. 10.1071/SH15175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wi T, Lahra MM, Ndowa F, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: global surveillance and a call for international collaborative action. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002344 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Speers DJ, Chua IJ, Manuel J, et al. Detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis from pooled rectal, pharyngeal and urine specimens in men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect 2018;94:293–7. 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028162supp001.pdf (224.2KB, pdf)