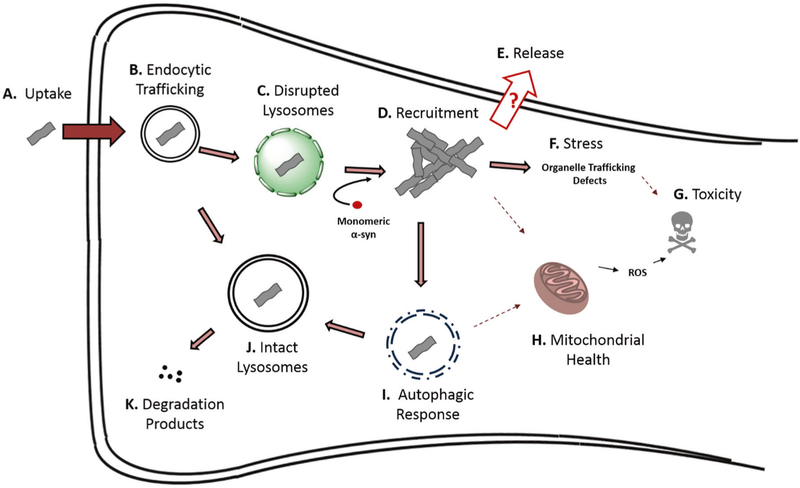

Fig. 1.

Proposed life cycle of α-syn seeds in the cell. a Multiple mechanisms have been shown to mediate α-syn fibril uptake into cells, including receptor-mediated endocytosis and fluid-phase endocytosis. Additionally, it has been demonstrated in model systems that various extracellular vesicles or tunneling nanotubes can mediate α-syn entry. b After endocytosis, fibrils are trafficked via the endocytic pathway to lysosomes where many remain sequestered (See J). If α-syn PFF uptake bypasses endocytosis, as in the case of some microvesicle, endosome, or tunneling nanotube-mediated transmission, these α-syn PFFs can likely reach the cytosol where they can immediately recruit monomeric α-syn into pathological inclusions. c If lysosomes are impaired due to genetic anomalies, age, or if the α-syn fibrils themselves disrupt and cross the lysosomal membrane, fibrils can escape to the cytosol where they d interact with and recruit monomeric α-syn into mature intracellular inclusions. e Release of pathogenic α-syn seeds is thought to be possible, although specific mechanisms are poorly understood. f α-Syn inclusions can stress the cells by various means, leading to loss of specific cellular functions and eventually cell death. This may be mediated in some contexts by (h) impaired mitochondrial function. i Cells can mount an autophagic response to inclusions, possibly disrupting mitophagy and inhibiting autophagic flux. j Internalized fibrils can remain sequestered in intact lysosomes. Also, it is possible that some aggregated α-syn species can become degraded in lysosomes via autophagy, k resulting in the production of α-syn degradation products which may be less or more pathogenic than full length α-syn PFFs. Biochemically-distinct α-syn strains (see discussion of strains below) likely exhibit different behaviors at each or any of these steps, potentially resulting in different disease manifestations