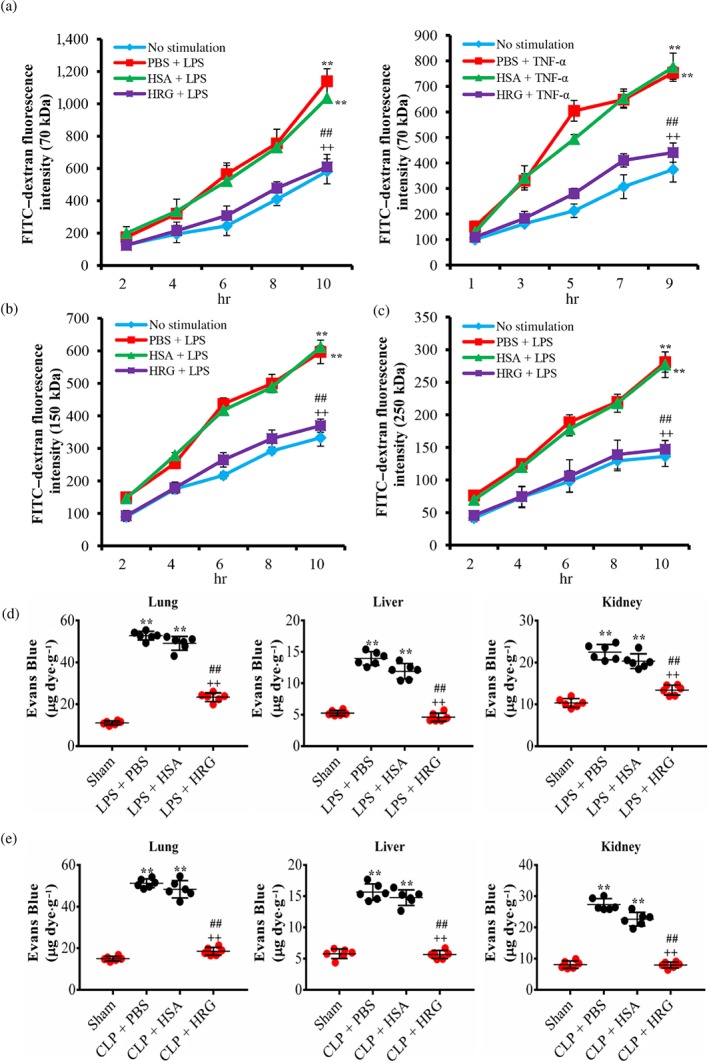

Figure 6.

Protective effects of histidine‐rich glycoprotein (HRG) on endothelial permeability in vitro and in vivo. (a–c) Effects of HRG on LPS/TNF‐α‐induced hyperpermeability of the endothelial monolayer. The graph shows the fluorescence intensity of FITC–dextran leakage, at different sizes, from transwell filters to the lower chamber. Data are means ± SEM (n = 5 per group). One‐way ANOVA followed by the post hoc Fisher test, **P < .05 versus control, ## P < .05, and ++ P < .05 versus PBS and human serum albumin (HSA). (d) Mice were given an i.v. injection of LPS (10 mg·kg−1) and then treated with HRG or HSA (20 mg·kg−1) for 12 hr. (e) Mice were subjected to caecal ligation puncture (CLP) or a sham operation and then an immediate i.v. injection of HRG or HSA. At 12 or 24 hr later, the mice received an i.v. injection of Evans blue dye (EBA), and EBA extraction was measured in the lung, liver, and kidney to assess vascular permeability (n = 6 per group). The extracted dye was then measured with a spectrometer at 610 nm. The absorbance value was converted to μg Evans blue dye.g‐1 wet weight of lung, liver, or kidney respectively. Statistical analysis was performed by one‐way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post hoc test, **P < .05 versus sham, ## P < .05, and ++ P < .05 versus PBS and HSA respectively