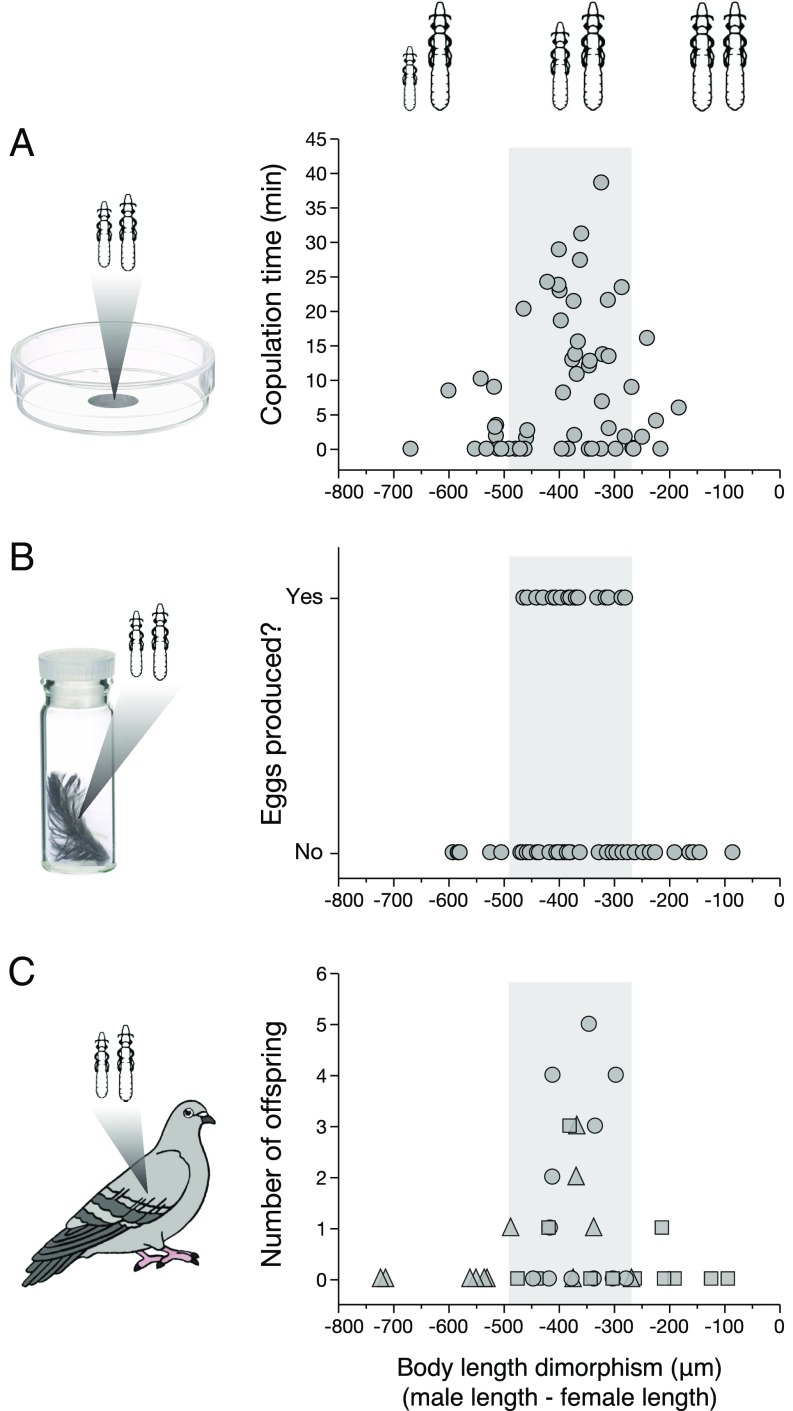

Fig. 4.

Reproductive performance of C. columbae differing in size dimorphism. Values on the x axis indicate the difference in body length of the male relative to that of the female (e.g., “−400 μm” represents a trial in which the male was 400 μm shorter than the female). Gray shaded region in each plot represents the typical range of dimorphism of lice (SI Appendix, Table S6); relatively small males at left, large males at right (illustrations not to scale). (A) Copulation time of lice in mating arenas was correlated with size dimorphism (NLM, n = 56, t = −2.30, P = 0.03; SI Appendix, Table S7). (B) Pairs of lice with typical degrees of dimorphism were more likely to produce eggs (GNLM, n = 58, z = −1.96, P < 0.05; SI Appendix, Table S8); 17 of 42 typical pairs (40.5%) produced eggs, but none of 16 pairs (0.0%) with relatively small or large males produced eggs. (C) Reproductive success of 36 pairs of lice from feral or giant runt pigeons transferred to 36 louse-free feral pigeons: 12 pairs included a male giant runt louse and a female feral pigeon louse (squares); 12 pairs included a male feral pigeon louse and a female giant runt louse (triangles); 12 (control) pairs included a male feral pigeon louse and a female feral pigeon louse (circles) (SI Appendix, Table S9). Pairs with intermediate levels of dimorphism produced significantly more offspring than pairs with extreme dimorphism (GLNMM, n = 36, z = −2.21, P = 0.03; SI Appendix, Table S10). Reproductive success was governed by the relative size of the male and female lice, independent of the type of host on which they evolved (compare circles, triangles, and squares).