This study examines the characteristics of the reported industry payments made to ophthalmologists in the Open Payments Database from 2013 to 2017.

Key Points

Question

What are the characteristics of the reported industry payments made to ophthalmologists in the Open Payments Database?

Findings

In this analysis, the Open Payments Database reported a total of 20 943 ophthalmologists receiving 736 517 payments worth more than half a billion dollars (median payment per ophthalmologist, $637.75) during a 5-year period (2013-2017). Distribution was skewed, with few ophthalmologists receiving the most funding.

Meaning

Although the veracity of the industry payment reports cannot be confirmed, the findings suggest that ophthalmologists' receipt of industry payments are extensive, which could be associated with possible conflicts of interest and biased clinical practices.

Abstract

Importance

An increased awareness of the interactions between the medical industry and health care professionals may lead to lower health care costs and more effective health care practices.

Objective

To assess the characteristics of industry payments made to ophthalmologists between 2013 and 2017.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This analysis included data reported in the June 29, 2018, update of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments Database (OPD). The OPD contains public records of industry payments made to physicians and teaching hospitals from August 1, 2013, to December 31, 2017, as reported by the medical industry. All general or research payments distributed to US ophthalmologists and contained in the OPD were included in this study. Data are summarized by practitioner, manufacturer, payment category, and geographic location.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Main outcomes were the distribution, quantity, and value of payments made to ophthalmologists practicing in the United States or US territories. The financial characteristics of payment category, manufacturer, product, and location were also assessed.

Results

This analysis revealed that the OPD showed industry reporting a total of 20 943 ophthalmologists receiving 736 517 payments worth $543 679 603.53 (1.67% of all industry-reported funds in the OPD). The median payment value was $22.44. Most payments were for food and beverages (581 588 [78.96%]), whereas most funds were allocated toward research ($310 142 151.88 [57.05%]) and consulting fees ($73 565 327.71 [13.51%]). The median payout to each ophthalmologist was $637.75 (interquartile range, $167.33-$2065.54). California was the highest-grossing state, receiving $101 135 980.34 (18.60%) of all payments. Fifteen companies were responsible for 87.68% of all funds distributed ($476 719 470.11) and were mostly involved in the production of pharmaceutical agents (anti–vascular endothelial growth factor agents, glaucoma eyedrops, and ocular lubricants) and surgical devices (cataract and glaucoma).

Conclusions and Relevance

Although there is no way to know the veracity of these reports, the findings suggest the financial ophthalmologist-industry relationship is substantial. These relationships may be adding to health care costs and affecting the quality of care, although those associations were not evaluated in this study.

Introduction

The Open Payments Database (OPD) was established by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to report the financial interactions between the medical industry and health care professionals, as mandated by the Physician Payments Sunshine Act of 2010, part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. The 2018 report describes financial information between August 1, 2013, and December 31, 2017. During this period, the OPD reported that $32.49 billion dollars’ worth of research and general payments were distributed from the medical industry to physicians and teaching hospitals.1

An early analysis of the OPD indicated that 9855 ophthalmologists received $10 926 447 during 5 months in 2013 alone, mostly in the form of consulting fees.2 To date, no study of which we are aware has described the long-term financial interactions between the medical industry and ophthalmologists using all the available data in the CMS OPD. Herein, we quantified and identified the nature of industry payments made to ophthalmologists from 2013 to 2017 in hopes that increased transparency of these payments may lead to more evidence-based and cost-effective health care practices.

Methods

This analysis used data from the June 29, 2018, update of the CMS OPD general and research payments reported from August 1, 2013, to December 31, 2017. This database is free and publicly available (https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/).1 The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board does not require formal approval for research studies that use publicly available data sets. No informed consent was required because this was a publicly available data set. All data were deidentified.

Ownership payments were excluded because of inadequate context for interpretation. General payments are payments for food and beverage, education, speaker or faculty compensation, consulting, travel and lodging, honoraria, gifts, grants, ownership or investment interest, royalty or licensing, charitable contributions, and entertainment.

Speaker or faculty compensation includes compensation relating to nonaccredited and noncertified continuing educational programs, accredited and certified continuing educational programs, and compensation for speaking or faculty roles not pertaining to continuing educational programs.

Research payments specifically pertain to a research agreement or protocol. Definitions of the payment types are found on the CMS OPD website.1 General payments were correlated with the physician receiving the payment, whereas research payments were correlated with the principal investigator of the study.

Microsoft Excel software, version 16.0 (Microsoft Corp) was used for all data collection, processing, and analysis. Files too large to be processed (exceeding 1 048 576 rows) were fragmented using file-splitting freeware (CSV Splitter; ERD Concepts). Each data set was filtered to include only physicians and osteopaths practicing ophthalmology in the United States and its territories.

The number and value of payments made to ophthalmologists from the medical industry are described in overall terms and subcategorized by payment nature, practitioner, manufacturer, product, and geographic location. We used the physician profile identification number to identify physicians and the applicable manufacturer identification number to identify manufacturers (the physician profile identification number is a unique identifier for a physician within the OPD and is not related to the provider’s National Provider Identification number). Manufacturer payment identification numbers corresponding to entities of the same company were combined and reported as a single manufacturer. The central tendency and statistical dispersion were described by medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Means and SDs were not used because the data were skewed toward larger payment values. Data were compared using 2-tailed equal variance t tests at a significance level of P < .05.

Results

Overview of Ophthalmology-Related Payments

Between 2013 and 2017, physicians who practice ophthalmology received 736 517 payments worth $543 679 603.53 (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The median payment value was $22.24 (IQR, $13.53-$108.51), with 535 636 payments (72.73%) valued under $100. Transactions were mostly general payments (n = 683 776 [92.84%]). Research payments (median, $1114.60; IQR, $471.28-$4000.00) were substantially higher in value than general payments (median, $20.60; IQR, $13.03-$88.54) (P < .001). The highest-valued transaction was a royalty or licensing payment worth $8 312 689.70.

Ophthalmology-Related Payments by Payment Category

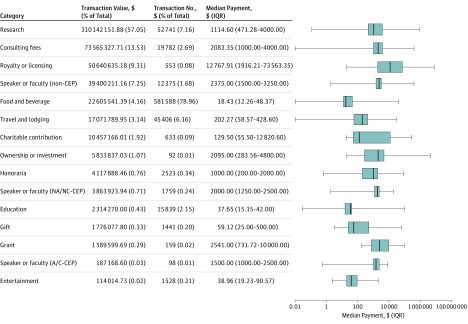

The top-funded categories were research ($310 142 151.88 [57.05%]) and consulting ($73 565 327.21 [13.53%]). Entertainment was the least-funded category ($114 014.73 [0.02%]). Royalty and licensing had the highest median value at $12 767.91 (IQR, $1916.21-$73 563.35). Food and beverage payments had the lowest median value at $18.43 (IQR, $12.26-$48.37). Although food and beverage received the most transactions (581 588 [78.96%]), this category received only 4.16% of all funds ($22 605 541.39). Ownership and investments received the fewest transactions (92 [0.01%]). The Figure and eTable 2 in the Supplement report the categorical distribution of payments.

Figure. Distribution of Open Payments Database (OPD)–Reported Payments to Ophthalmologists (2013-2017), Ranked in Descending Order of Funds Received per Category.

The box and whisker plot is in logarithmic scale. The box represents the interquartile range (IQR), and the line within the box represents the median value. The whiskers denote the range of the data. A/C indicates accredited/certified; CEP, continuing education program; and NA/NC, nonaccredited/noncertified.

Ophthalmology-Related Payments by Payment Recipient

The OPD identified 20 943 different ophthalmologists who received industry payments between 2013 and 2017. The median value of payments received per ophthalmologist was $637.75 (IQR, $167.33-$2065.54) during multiple transactions (median, 13 payments). Most ophthalmologists (19 486 [93.04%]) received only general payments. Dollar amounts were significantly higher if research payments were received (median, $11 894.10; IQR, $4637.95-$43 990.82) for ophthalmologists receiving research funding only and $83 859.38 (IQR, $24 905.63-$309 253.69) for ophthalmologists receiving both research and general funding compared with ophthalmologists receiving only general payments (median, $542.76; IQR, $148.86-$1585.07) (P < .001) (eTable 3 in the Supplement). The most industry-compensated ophthalmologist received $12 403 539.59, largely in the form of royalty and licensing payments ($12 353 640.40 [99.60%]) and consulting fees ($24 725.00 [0.20%]).

Industry-sponsored meals were received by 20 306 different ophthalmologists (96.96%). The median value of food and beverage payments received per ophthalmologist was $502.14 (IQR, $149.61-$1282.48), typically obtained for multiple meals (median, 12 food and beverage payments; IQR, 3-36 food and beverage payments).). The most food and beverage funding received by 1 ophthalmologist was $39 307.01, and the highest number of food and beverage payments received by 1 ophthalmologist was 1157 payments worth $22 800.71.

Consulting fees were received by 2048 ophthalmologists (9.78%). The median consulting fee received per ophthalmologist was $4800 (IQR, $1750-$18 788.75). The highest-paid consulting ophthalmologist received $3 363 564.25. The most consulting payments received by an ophthalmologist was 241 payments worth $1 070 461.56.

Speaker or faculty compensation was received by 1756 ophthalmologists (8.38%). The median speaker or faculty fee received per ophthalmologist was $3600 (IQR, $750-$17 115). The highest-paid lecturing ophthalmologist received $1 729 897.86 (all within a single year). The most speaker or faculty payments distributed to an ophthalmologist were 167 payments worth $309 610.40.

Research compensation was received by 1457 ophthalmologists (6.96%). The median research payment received per ophthalmologist was $49 360.43 (IQR, $11 900.00-$189 225.40). The highest-paid researcher-ophthalmologist received $6 875 786. The most research payments obtained by an ophthalmologist was 853 payments worth $945 558.54.

Royalty or licensing compensation was received by 93 ophthalmologists (0.44%). The median royalty or licensing payments received per ophthalmologist was $42 755.22 (IQR, $5000.00-$157 245.00). The ophthalmologist with the most royalties or licensing compensation received $12 353 630.40 (also the highest industry-paid ophthalmologist overall). The most royalty or licensing payments received by an ophthalmologist were 48 payments worth $2 440 890.51.

Ophthalmology-Related Payments by Manufacturer

Collectively, ophthalmologists received payments from 520 drug or device manufacturers (eTable 4 and eTable 5 in the Supplement). Fifteen manufacturers (2.88%) were responsible for 640 807 transactions (87.01%), representing $476 719 470.11 (87.68%) of all payments (Table 1). The median value distributed per manufacturer was $836.77 (IQR, $117.91-$36 284.75). The manufacturer distributing the most funds ($97 397 047.56 [17.91%]) was Alcon Inc, which dispersed the bulk of funds in the form of royalties or licenses ($39 522 550.04 [40.58%]), research ($22 972 331.64 [23.59%]), and consulting ($16 321 747.38 [16.76%]). Allergan PLC distributed the most payments (203 490 [27.63%]) and had the largest outreach of any company, making payments to 13 727 ophthalmologists (65.54%).

Table 1. Top 15 Manufacturers Making Payments to Ophthalmologists, as Reported by Industry in the OPD (2013-2017)a.

| Manufacturer (No. of MIDs)b | Payments, $ (%) (n = $543 679 603.53) | Payments, No. (%) (n = 736 517) | Ophthalmologists Receiving Funds, No. (%) (n = 20 943) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcon Inc (5) | 97 397 047.56 (17.91) | 184 878 (25.10) | 13 575 (64.82) |

| Genentech Inc (2) | 95 674 381.40 (17.60) | 34 034 (4.62) | 3765 (17.98) |

| Allergan PLC. (1) | 80 618 171.48 (14.83) | 203 490 (27.63) | 13 727 (65.54) |

| Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc (2) | 71 325 106.12 (13.12) | 28 615 (3.89) | 4109 (19.62) |

| Valeant Pharmaceuticals Inc (1) | 24 206 946.74 (4.45) | 51 309 (6.97) | 8640 (41.25) |

| Glaukos Corporation (1) | 23 889 440.41 (4.39) | 12 030 (1.63) | 3442 (16.44) |

| Abbott Laboratories Inc (1) | 17 780 578.82 (3.27) | 31 307 (4.25) | 6451 (30.80) |

| Johnson & Johnson Inc (4) | 13 968 373.83 (2.57) | 12 601 (1.71) | 3978 (18.99) |

| Shire PLC (2) | 13 851 897.46 (2.55) | 54 746 (7.43) | 9301 (44.41) |

| Novartis Corporation (3) | 8 433 269.46 (1.55) | 1530 (0.21) | 491 (2.34) |

| Ocular Therapeutix Inc (1) | 7 718 429.08 (1.42) | 1782 (0.24) | 327 (1.56) |

| AbbVie Inc (1) | 7 400 260.56 (1.36) | 4217 (0.57) | 970 (4.63) |

| Par Pharmaceutical Inc (1) | 5 181 417.80 (0.95) | 16 (0.00) | 3 (0.01) |

| Bausch & Lomb Incc (1) | 4 903 128.11 (0.90) | 20 011 (2.72) | 5541 (26.46) |

| Transcend Medical Inc (1) | 4 371 021.28 (0.80) | 241 (0.03) | 55 (0.26) |

Abbreviations: MIDs, manufacturer identification numbers; OPD, Open Payments Database.

Data are presented in descending order of manufacturer payments (value).

There were often multiple MIDs associated with the same company.

Name change to Bausch Health Companies effective May 2018.

Ophthalmology-Related Payments by Product

Product-specific information was present in 598 030 general payment descriptions (87.46%) and 31 038 research payment descriptions (58.85%). Many entries, however, were labeled with incomplete or ambiguous descriptions (ie, cataract equipment) in which product-specific information could not be determined. The data that contained product-specific payment information were used to determine the most funded products for general and research payments (Table 2). The top 10 general marketed products totaled $67 949 642.48 (29.10% of general payments). Of these payments, the Cypass MicroStent (Alcon Inc) was the highest valued ($11 509 681.91) and cyclosporine (Restasis; Allergan Inc) was the most mentioned (n = 77 807). The top 10 research marketed products totaled $108 192 423.90 (34.88% of research payments). Of these payments, aflibercept (EYLEA; Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc) was the highest valued ($35 178 054.46) and bimatoprost (Lumigan; Allergan Inc) was the most mentioned (n = 3174).

Table 2. Top Products Associated With Payments to Ophthalmologists, as Reported by Industry in the OPDa.

| Productb | Manufacturer | Payment Value, $ (%) | Payments, No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top Products Funded by General Payments (n = $233 537 451.65 Payment Value and 683 776 Payments) | |||

| Cypass Microstent | Alcon Inc | 11 509 681.91 (4.93) | 2409 (0.35) |

| Lucentis (ranibizumab) | Genentech Inc | 9 747 450.11 (4.17) | 26 222 (3.83) |

| Restasis (cyclosporine) | Allergan Inc | 7 313 632.92 (3.13) | 77 807 (11.38) |

| Ozurdex (dexamethasone IVI) | Allergan Inc | 7 051 701.50 (3.02) | 24 393 (3.57) |

| EYLEA (aflibercept) | Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc | 6 820 971.23 (2.92) | 22 384 (3.27) |

| Xiidra (lifitegrast) | Shire Plc | 5 979 910.37 (2.56) | 48 662 (7.12) |

| Besivance (besifloxacin) | Bausch & Lomb Incc | 5 489 010.03 (2.35) | 14 367 (2.10) |

| Lotemax gel (loteprednol) | Bausch & Lomb Incc | 5 036 277.28 (2.16) | 22 122 (3.24) |

| Prolensa (bromfenac) | Bausch & Lomb Incc | 4 581 407.18 (1.96) | 20 713 (3.03) |

| Tecnis IOLsd | Johnson & Johnson Inc | 4 419 599.95 (1.89) | 18 202 (2.66) |

| Top Products Funded by Research Payments (n = $310 142 151.88 Payment Value and 52 741 Payments) | |||

| EYLEA (aflibercept) | Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc | 35 178 054.46 (11.34) | 2616 (4.96) |

| Lucentis (ranibizumab) | Genentech Inc | 33 446 700.92 (10.78) | 1813 (3.44) |

| Lumigan (bimatoprost) | Allergan Inc | 15 307 842.41 (4.94) | 3174 (6.02) |

| Humira (adalimumab) | AbbVie Inc | 5 037 301.93 (1.62) | 673 (1.28) |

| Healon OVD (sodium hyaluronate) | Johnson & Johnson Inc | 4 534 731.31 (1.46) | 829 (1.57) |

| Tecnis IOLsc | Johnson & Johnson Inc | 3 854 879.66 (1.24) | 717 (1.36) |

| Cypass MicroStent | Alcon Inc | 3 613 297.85 (1.17) | 414 (0.78) |

| Ozurdex (dexamethasone IVI) | Allergan Inc | 2 896 020.72 (0.93) | 370 (0.70) |

| Gilenya (fingolimod) | Novartis AG | 2 380 470.63 (0.77) | 40 (0.08) |

| Ilevro (nepafenac) | Alcon Inc | 1 943 124.01 (0.63) | 1648 (3.12) |

Abbreviations: IOL, intraocular lens; IVI, intravitreal implant; OPD, Open Payments Database; OVD, ophthalmic viscoelastic device.

Data are presented in descending order of payments (value) associated with the product.

Brand names were listed in the OPD. The generic name is also reported, if applicable.

Name change to Bausch Health Companies effective May 2018.

Technis 1-piece, 3-piece, multifocal, and toric IOL subtypes combined because of ambiguity in listing descriptions.

Ophthalmology-Related Payments by Location

Ophthalmology-related payments were distributed to each of the 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Guam, the Virgin Islands of the United States, and US Army Post Office (APO) zip codes (eTable 6 in the Supplement). Only 1 general payment worth $16.12 was unable to be traced to a specific geographic location. The median payment received per location was $4 253 683.93 (IQR, $721 648.38-$12 985 812.40). In total, 5 locations received nearly half of all industry funds ($251 387 881.80 [46.24%]): California ($101 135 980.34 [18.60%]), Texas ($56 176 819.21 [10.33%]), Florida ($41 174 317.80 [7.57%]), New York ($28 428 528.95 [5.23%]), and Massachusetts ($24 472 235.51 [4.5%]). California also received the highest number of payments of any location (105 458 [14.32%]). Industry funding positively correlated with population data (r2 = 0.90). Only 6 locations did not receive research funding: Alaska, APO zip codes, Delaware, Guam, Rhode Island, and the US Virgin Islands.

Discussion

The OPD showed industry reporting that 20 943 ophthalmologists received 736 517 payments, worth $543 679 603.53 (1.67% of all general and research funds disclosed in the OPD) from August 1, 2013, to December 31, 2017.1 Industry payments to ophthalmologists were typically involved in the marketing or development of anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents, glaucoma management (surgical and medical), and products for cataract surgery. The geographic distribution of industry payments was proportional to national population data, with the top-grossing states being the most populated and having the most ophthalmologists.3,4

The number of ophthalmologists reported to have received industry payments in this study (n = 20 943) is higher than the number of active ophthalmologists identified by the American Academy of Ophthalmology (n = 19 216) and the American Medical Association (n = 18 817).5,6,7 The discrepancy is most likely attributable to the erroneous labeling of nonophthalmologists as ophthalmologists in the OPD. Despite not knowing the precise number of ophthalmologists receiving industry funds, the estimated figure from the OPD data suggests that most ophthalmologists interacted with the medical industry in some respect in 2013 to 2017.

Other specialties have also reported a high level of physician interaction with the medical industry.8,9,10 An analysis of 28 medical specialties from the 2014 OPD data indicated that the reported physician interaction in each specialty was a mean of 58.1% (range, 14.6%-91.1%), with ophthalmology ranking the eighth highest overall (71.4%).10 Physician acceptance of industry payments may lead to many potential implications, including conflicts of interest, dissemination of inaccurate knowledge about the sponsor’s or a competitors’ product, and more frequent prescribing of brand name medications that have equally effective generic counterparts.11,12,13 The latter implication has been shown to directly increase the health care cost to the patient.13

Although individual payments reported in the OPD were typically low in value (median, $22.24), the value that each ophthalmologist was reported to have received was substantially higher (median, $637.75); reflecting the multiple payments typically received by ophthalmologists over time. Although most ophthalmologists (12 516 [59.78%]) were reported to have received less than $1000.00, most funds ($434 348 114.77 [79.89%]) were dispersed among 2866 ophthalmologists (13.69%) who were consultants, researchers, or received royalty or licensing payments. The manufacturers making the most payments to ophthalmologists were also top payers in dermatology (n = 5), obstetrics and gynecology (n = 1), and plastic surgery (n = 1).8,14,15

Similar to other specialties, ophthalmologists were reported to have received most payments in the form of meals.2,8,9,10,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21 Although perhaps seemingly benign to the recipient, the acceptance of industry payments (especially meals) is not without potential consequence. A dose-dependent prescribing bias has been demonstrated in nonophthalmologists receiving even 1 industry-sponsored meal.16 Similarly, ophthalmologists receiving industry payments promoting anti-VEGF agents (typically during a meal) were more likely to prescribe costlier anti-VEGF agents (aflibercept and ranibizumab) compared with bevacizumab, although an association does not equate to a cause-and-effect relationship.22,23 With nearly all physicians in our study reported to have received meal payments from the medical industry, the magnitude of the industry-physician relationship is likely underestimated because of the inherent challenges of accurate reporting at large-scale events, such as continuing medical education courses or conferences. As such, the CMS does not require reporting of meals when it is difficult to identify who partakes in an offering (ie, buffets, coffee or tea, or snacks made available to all attendees) or the distribution of small incidental items (ie, pens and notepads) valued under $10.1

Although general payments include payments from the medical industry’s marketing arm and with a marketing goal in mind, research payments are more likely to be aimed at a basic level in developing new drugs and/or devices or meeting regulatory requirements, such as in phase 3 clinical trials. General payments are voluntary financial relationships between industry and physicians, whereas research payments fall more in line with necessary financial relationships to bring new drugs and devices to the marketplace. Medicine and industry must work together for the latter but do not need to work together to sell drugs and devices.

The higher costs associated with the research and development of pharmaceutical agents and medical devices account for the higher median cost of research payments compared with general payments ($1114.60 vs $20.60). The products receiving the most research funding were aflibercept and ranibizumab, both of which are used in the treatment of the most common cause of irreversible blindness in people older than 60 years in the United States: age-related macular degeneration. The remainder of the top products funded by research and general payments were largely associated with the management of ocular inflammation, glaucoma, cataracts, and dry eye.

The medical industry benefits from having influential physicians (key opinion leaders) speak on behalf of a product. Therefore, consulting is one of the top-funded categories across surgical specialties, including ophthalmology.2,8,10,15,17,19,20,21 Similarly, royalty payments made to physicians are expected to be more prevalent in specialties that are more drug or device intensive. The percentage of royalties distributed as general payments to ophthalmologists (21.68%) was less than that reported to have been received by neurosurgeons (74%), orthopedic surgeons (69%), and obstetrician-gynecologists (50%) but higher than royalty payments distributed to pediatricians (15%), plastic surgeons (4%), urologists (11%), otolaryngologists (2.4%), cardiothoracic surgeons (3.8%), dermatologists (0.3%), and emergency medicine physicians (1.4%).8,10,14,15,17,19,24,25,26,27

Although the CMS OPD is free and publicly available, most of the population is unaware of this resource. Results from a 2018 ophthalmologic survey of 407 participants indicated that only 30 patients (7.7%) knew of the OPD and only 12 (3.1%) attempted to access the database (11 patients [2.8%] in this study were physicians).28 Those who attempt to analyze data in the OPD are often limited by the large size of the data files. Although there is also an online search tool to access the data, the interface is most useful for queries on a specific physician and does not easily allow for broad analysis of the data. A more user-friendly website or the separation of the data files into individual specialties may lead to more useful information about physicians receiving industry payments.

The OPD serves as an invaluable tool to better understand the financial interactions between health care professionals and the medical industry. However, the database remains underused 5 years after the initial data set was released. The central flaws of the database appear to be a lack of public awareness of the registry, incomplete and inaccurate data, and difficulty managing the extent of the data. To achieve the ultimate goals of the Physician Payments Sunshine Act and the lowering of health care costs through increased financial transparency between the medical industry and health care professionals, all these issues would likely be of benefit if addressed.

Limitations

This study is most limited by the accuracy of the data reported in the OPD. Better standardization and more complete descriptions would lead to more useful and accurate analyses. To determine the accuracy of our data, the ophthalmologists receiving the most funds and most transactions across 5 categories (consulting, royalties or licensing, research, speaker or lecturer, and food and beverage) were manually cross-checked in the OPD. Overall, the financial data reported in our study corresponded with 98.67% accuracy to the OPD. Of the 10 physicians manually crosschecked, 9 were ophthalmologists and 1 was an otolaryngologist; confirming our assumption that some nonophthalmologists are erroneously labeled as ophthalmologists in the CMS OPD. Only 1 ophthalmologist was a woman, consistent with a previous report that female ophthalmologists receive less industry payments compared with their male counterparts.29 In addition, the true extent of the industry-physician relationship is underestimated in our study in part because the Physician Payments Sunshine Act mandates reporting only for companies that provide products covered by government-sponsored programs (Medicare, Medicaid, and Children’s Health Insurance Program) and the gifting of medication samples, commonplace in many ophthalmologic practices, is also exempt from reporting.8,9 In addition, the breadth of information contained in the database limited the number of analyses that could reasonably be published in a single study. Further investigations are needed to explore the nature and scope of industry payments as they pertain to the ophthalmic subspecialty, practice type (private vs academic), physician demographics (age and sex), and the degree of the financial relationships that researchers have with their industry sponsor and to elucidate the implications of generic products and noninterventional treatment approaches that do not receive marketing attention from the medical industry.

Conclusion

Although the veracity of industry payment reports cannot be confirmed, the findings suggest that ophthalmologists’ receipt of industry payments is extensive. Although this relationship has the potential to foster innovation and improve health care needs, ophthalmologists should remain aware that the medical industry is composed of profit-dependent companies and that each interaction with industry has the potential to influence the prescribing or practicing patterns of the physician.

eTable 1. Ophthalmology related industry payments (2013-2017), as reported in the OPD

eTable 2. Ophthalmology related industry payments (2013-2017) as reported in the OPD, by payment category

eTable 3. Ophthalmology related industry payments (2013-2017) as reported in the OPD, by payments received per provider

eTable 4. Ophthalmology related industry payments (2013-2017) as reported in the OPD, by funds distributed per manufacturer

eTable 5. Ophthalmology related industry payments (2013-2017) in the OPD, per manufacturer

eTable 6. Ophthalmology related payments (2013-2017) received per location, as reported in the OPD

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2019. https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov. Accessed January 15, 2019.

- 2.Chang JS. The Physician Payments Sunshine Act: data evaluation regarding payments to ophthalmologists. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(4):656-661. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Board of Ophthalmology Verify a physician. https://abop.org/verify-a-physician/ Accessed January 15, 2019.

- 4.United States Census Bureau American fact finder. Annual estimates of the resident population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2017. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=PEP_2017_PEPANNRES&src=pt. Accessed January 15, 2019.

- 5.American Academy of Ophthalmology Eye health statistics. https://www.aao.org/newsroom/eye-health-statistics#_edn25. Accessed January 15, 2019.

- 6.Williams RD. Eye surgery on eye surgeons: what’s it like? Eyenet; 2016:14. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Association of American Medical Colleges Number of people per active physician by specialty, 2017. https://www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/492558/1-2-chart.html. Accessed January 15, 2019.

- 8.Feng H, Wu P, Leger M. Exploring the industry-dermatologist financial relationship: insight from the Open Payment Data. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(12):1307-1313. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell EG, Gruen RL, Mountford J, Miller LG, Cleary PD, Blumenthal D. A national survey of physician-industry relationships. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(17):1742-1750. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleischman W, Ross JS, Melnick ER, Newman DH, Venkatesh AK. Financial ties between emergency physicians and industry: insights from open payments data. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(2):153-158.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziegler MG, Lew P, Singer BC. The accuracy of drug information from pharmaceutical sales representatives. JAMA. 1995;273(16):1296-1298. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520400066047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larkin I, Ang D, Steinhart J, et al. . Association between academic medical center pharmaceutical detailing policies and physician prescribing. JAMA. 2017;317(17):1785-1795. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.4039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansen ME, Richardson C. Estimation of potential savings through therapeutic substitution. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(6):769-775. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tierney NM, Saenz C, McHale M, Ward K, Plaxe S. Industry payments to obstetrician-gynecologists: an analysis of 2014 open payments data. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(2):376-382. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed R, Lopez J, Bae S, et al. . The dawn of transparency: insights from the physician payment sunshine act in plastic surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2017;78(3):315-323. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeJong C, Aguilar T, Tseng CW, Lin GA, Boscardin WJ, Dudley RA. Pharmaceutical industry-sponsored meals and physician prescribing patterns for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1114-1122. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samuel AM, Webb ML, Lukasiewicz AM, et al. . Orthopaedic surgeons receive the most industry payments to physicians but large disparities are seen in sunshine act data. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(10):3297-3306. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4413-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rathi VK, Samuel AM, Mehra S. Industry ties in otolaryngology: initial insights from the physician payment sunshine act. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(6):993-999. doi: 10.1177/0194599815573718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed R, Bae S, Hicks CW, et al. . Here comes the sunshine: industry’s payments to cardiothoracic surgeons. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(2):567-572. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.06.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmed R, Chow EK, Massie AB, et al. . Where the sun shines: industry’s payments to transplant surgeons. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(1):292-300. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee KC, Chuang SK, Jazayeri HE, Koch A, Eisig SB. Industry payments in oral and maxillofacial surgery: a review of 112,478 payments from a national disclosure program [published online November 30, 2018]. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2018.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor SC, Huecker JB, Gordon MO, Vollman DE, Apte RS. Physician-industry interactions and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor use among US ophthalmologists. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(8):897-903. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.1678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh N, Chang JS, Rachitskaya AV. Open payments database: anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agent payments to ophthalmologists. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;173:91-97. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Lotbiniere-Bassett MP, McDonald PJ. Industry financial relationships in neurosurgery in 2015: analysis of the sunshine act open payments database. World Neurosurg. 2018;114:e920-e925. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.03.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morse E, Berson E, Mehra S. Industry involvement in otolaryngology: updates from the 2017 open payments database [published online March 26, 2019]. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;194599819838268. doi: 10.1177/019459981983268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Modi PK, Farber NJ, Zavaski ME, Jang TL, Singer EA, Chang SL. Industry payments to urologists in 2014: an analysis of the open payments program. Urol Pract. 2017;4(4):342-347. doi: 10.1016/j.urpr.2016.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karas DJ, Bandari J, Browning DN, Jacobs BL, Davies BJ. Payments to pediatricians in the sunshine act. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2017;56(8):723-728. doi: 10.1177/0009922816670981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stein GE, Kamler JJ, Chang JS. Ophthalmology patient perceptions of open payments information. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(12):1375-1381. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.4167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reddy AK, Bounds GW, Bakri SJ, et al. . Representation of women with industry ties in ophthalmology. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(6):636-643. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Ophthalmology related industry payments (2013-2017), as reported in the OPD

eTable 2. Ophthalmology related industry payments (2013-2017) as reported in the OPD, by payment category

eTable 3. Ophthalmology related industry payments (2013-2017) as reported in the OPD, by payments received per provider

eTable 4. Ophthalmology related industry payments (2013-2017) as reported in the OPD, by funds distributed per manufacturer

eTable 5. Ophthalmology related industry payments (2013-2017) in the OPD, per manufacturer

eTable 6. Ophthalmology related payments (2013-2017) received per location, as reported in the OPD