Abstract

Background

In countries with public health system, hospital bed reductions and increasing social and medical frailty have led to the phenomenon of “outliers” or “outlying hospital in-patients.” They are often medical patients who, because of unavailability of beds in their clinically appropriate ward, are admitted wherever unoccupied beds are. The present work is aimed to systematically review literature about quality and safety of care for patients admitted to clinically inappropriate wards.

Methods

We performed a systematic review of studies investigating outliers, published in peer-reviewed journals with no time restrictions. Search and screening were conducted by two independent researchers (MLR and ER). Studies were considered potentially eligible for this systematic review if aimed to assess the quality and/or the safety of care for patients admitted to clinically inappropriate units. Our search was supplemented by a hand search of references of included studies. Given the heterogeneity of studies, results were analyzed thematically. We used PRISMA guidelines to report our findings.

Results

We collected 17 eligible papers and grouped them into six thematic categories. Despite their methodological limits, the included studies show increased trends in mortality and readmissions among outliers. Quality of care and patient safety are compromised as patients and health professionals declare and risk analysis displays. Reported solutions are often multicomponent, stress early discharge but have not been investigated in the control group.

Conclusions

Published literature cannot definitely conclude on the quality and safety of care for patients admitted to clinically inappropriate wards. As they may represent a serious threat for quality and safety, and moreover often neglected and under valued, well-designed and powered prospective studies are urgently needed.

KEY WORDS: medical outliers, clinically inappropriate wards, quality assessment, risk assessment, hospital administration

INTRODUCTION

In the last few years, progressive reductions in hospital beds, growing social and medical frailty that impedes hospital discharge, and an inadequate availability of community healthcare services have led to a severe lack of hospital beds. Consequently, emergency physicians are forced to admit patients to clinically inappropriate wards.

The so-called outlier, out-lying hospital in-patient, overflow, sleep-out, or boarder1–3 is a patient who, because of unavailability of hospital beds in his/her clinically appropriate ward, is admitted wherever an unoccupied bed is. In such a case, clinical management is provided by the medical staff of the clinically appropriate ward (generally, internal medicine), but care is delivered by nursing staff of the hosting ward. An example is a patient with pneumonia who, because for unavailability of beds in internal medicine, is admitted to a surgical ward.

About 7–8% of all admissions every year are outlier patients.2 The phenomenon is common, particularly in countries with a public health system, and could pose a serious threat for quality and safety of patient care.

The aim of the present work is to systematically review literature evidences about such a phenomenon that is another face of hospital overcrowding.

METHODS

We performed a systematic review of studies investigating outliers, published in peer-reviewed journals with no time and language restrictions.

We searched Medline/PubMed and EMBASE using the following terms: ((“Outlier” OR “out-lying hospital in-patient” OR “overflow” OR “sleep-out” OR “boarder” OR “bed-spaced patient” OR “clinically inappropriate ward” AND “mortality”, “length of stay”, “satisfaction”, “adverse event”, “medical error”, “patient safety”)).

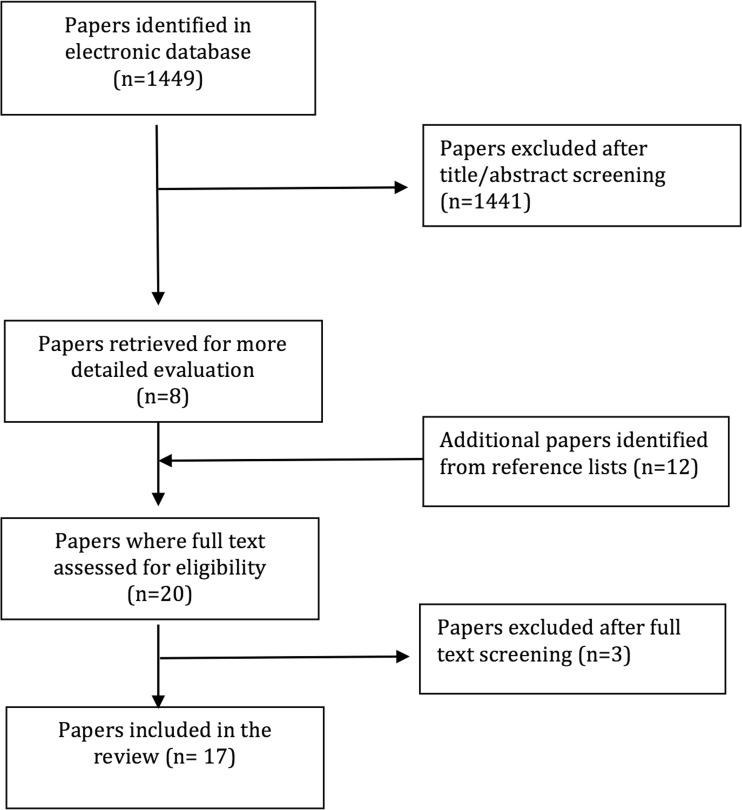

The search and screening were conducted by two independent researchers (MLR and ER). Studies were considered potentially eligible for this systematic review if aimed to assess the quality and/or the safety of care for patients admitted to clinically inappropriate units. Our search was supplemented by a hand search of references of included studies. Among them, we found some bed management policies available on hospital websites. They provide recommendations for a safe management of outliers. The search on Medline/PubMed and EMBASE using terms ((“bed management” AND “policy” OR “healthcare policy” OR “hospital utilization”)) did not produce useful results, so we decided not to include them in our review. Figure 1 shows the process and the results.

Figure 1.

Algorithm of study identification and selection.

Initially, we considered pooling some outcomes (mortality, length of stay, and readmission rates) but abstracted data yielded alarmingly high degrees of heterogeneity (I2 > 95%), so we decided to analyze our results thematically. Study characteristics were examined to explain differences in findings (Table 1). We used PRISMA guidelines to report our findings.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Included Studies

| Author, journal, and year | Country | Study setting | Sample (n) | Study design—data source | Study period | Outlier definition | Outcome/aims |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bai AD et al. BMJ Qual Saf 20184 | Canada | Tertiary hospital (440 beds), general internal medicine teaching units | 3243 (1125 outliers) | Retrospective, monocentric—administrative database | 1 Jan 2015–1 Jan 2016 | Patients bedspaced to off-service wards beds | All-cause mortality in hospital, LOS, readmissions |

| Stylianou N et al. BMJ Open 20171 | UK | District general hospital (565 beds), medical area | 71,038 patients spells (7021 outliers) | Retrospective, monocentric—administrative database | 2013/2014–2015/2016 | Hospital inpatient who was classified as a medical patient for an episode (time spent under the same consultant) within a spell and had at least one placement on a nonmedical ward within a spell | In-hospital mortality, 30-day mortality, length of stay, 30-day readmission to the same hospital |

| Novati R et al. Ann Ig 20175 | Italy | Regional hospital (490 beds) | 63,233 discharged patients before and 63,927 after | Before and after study, monocentric—administrative data | Before 2008–2011; after 2012–2015 | Not reported | Number of discharged patients, % of death, mean occupancy rate, % outlier days, ….. |

| Perimal L et al. BMC Geriatr. 20166 | Australia | Public teaching hospital (500 beds), medical area | 6367 patients with dementia (1000 outliers) | Retrospective, monocentric | 1 Jan 2007–22 Sept 2014 | Patient who spent ≥ 70% of his/her hospital stay outside home-ward | In-hospital LOS, in-hospital mortality, mortality within 48 h and 28 days, 7- or 28-day readmissions, discharge summary sent within 2 or 7 days |

| Goulding L et al. Health Expect 20152 | UK | Large NHS teaching hospital | 19 patients | Qualitative study (interviews) | Jan–April 2011 | A clinically inappropriate ward was defined | To explore patients’ perspectives about quality and safety of the care received on clinically inappropriate wards |

| Serafini F et al. Ital J Med 20157 | Italy | Public Hub Hospital (465 beds): internal medicine and geriatric units | 3828 (284 outliers) | Prospective monocentric—medical records | 2012 | Patients admitted in beds outside internal medicine and geriatrics | LOS, in-hospital mortality, and 30- and 90-day readmissions |

| Santamaria JD et al. Med J Aust 20148 | Australia | University-affiliated tertiary referral hospital (400 beds)—all areas | 11,034 outliers | Prospective, monocentric | 1 Jan 2009–30 Nov 2011 | Patients who spent time outside their home ward | The number of emergency call per hospital admission, with reference to location within the hospital |

| Perimal-Lewis L et al. Intern Med J 20139 | Australia | Public teaching hospital (500 beds)—medical area | 19,923 (2592 outliers) | Retrospective, monocentric—administrative database | 1 Jan 2003–20 Sept 2009 | Patient who spent ≥ 70% of his/her hospital stay outside home ward | In-hospital LOS, in-hospital mortality, mortality within 48 h and 28 days, 7- or 28-day readmissions, discharge summary sent within 2 or 7 days |

| Stowell A et al. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 201310 | France | University hospital | 493 (245 outliers) | Prospective, monocentric—administrative data | February–June 2010 | Inpatients that were outliers in inappropriate wards because of lack of beds | LOS, mortality at 24 h, 28 days, 3 months; 30-day readmission; rate of transfer to ICU |

| Goulding L et al. BMJ Qual Saf 20123 | UK | Large NHS teaching hospital (1100 beds) | 29 healthcare operators | Qualitative study (interviews) | Jan–July 2010 | Not reported | To explore NHS staff members’ perceptions and experiences of the contributory factors that may underpin safety in outliers |

| Creamer GL et al. ANZ Journal of Surgery 201011 | New Zealand | City Hospital—surgical ward | NA | Prospective, monocentric—data sheet fulfilled by 3 final year medical students | Not reported | Patients admitted to other wards as “overflow” | Ward round activities compared among outlying ward, acute ward, and home ward patients |

| Warne S et al. Nurs Crit Care 201012 | UK | Four acute hospitals—medical and surgical wards | 162 medical and surgical patients | Prospective, monocentric (point prevalence survey) | March 2007 | Medical patients managed on surgical wards | Impact of outlier status on medication administration |

| Alameda C et al. Eur J Intern Med 200913 | Spain | Public University Hospital (500 beds)—internal medicine (patients with diagnosis of heart failure DRG 127) | 243 (109 outliers) | Retrospective, monocentric—administrative data | 2006 | A patient admitted to a ward different from internal medicine ward | LOS, 30-day readmission with the same DRG, mortality, intra-hospital morbidity (composite endpoint) |

| Lepage B et al. Quality & Safety in Healthcare 200914 | France | Teaching hospital | Not applicable | Prospective, monocentric risk analysis | 2004–2006 | Patients hospitalized in a ward different from appropriate ward | To identify failure modes and priority ranking in outliers care process |

| Rae B et al. Aust Health Rev 200715 | New Zealand | Tertiary hospital | Not applicable |

Retrospective monocentric—administrative data Continuous quality improvement project evaluation |

1997 | Patients housed outside the contiguous home ward | To solve bed crisis |

| Gilligan S and Walters M Clinical Governance 200716 | UK | City hospital (650 beds) | Not applicable |

Prospective, monocentric— continuous quality improvement project evaluation |

2004 | Patients out from a specialty bed pool | To improve patients flow and reduce outliers |

| Ashdown DA et al. Annals of the royal College of Surgery England 200317 | UK | City General Hospital—surgical area | Not retrieved data | Audit | 2001–2002 | Not retrieved data | The number of operations canceled per specialty per day |

RESULTS

Our research retrieved 17 eligible papers, mainly studies conducted on medical patients. We divided them in six thematic categories according to the investigated outcome (details in Table 2a–g).

Table 2.

Results of eligible studies grouped in six thematic categories

| a. Mortality | |||

| Author/year | Measure | Results (outliers vs non outliers) | p |

| Bai AD et al. 20184 | Hazard ratio (HR) | ↑ 3.42 on admission decreases by 0.97 per day | p < 0.0001 |

| Stylianou N. et al. 20171 | Odds ratio (OR) | = outliers are not associated with in-hospital mortality (OR 0.983) | p = 0.773 |

| Serafini F. et al. 20157 | Hazard ratio (HR) | ↑ for outliers in surgical wards (1.8, 1.2–2.5 95% CI) | p < 0.05 |

| Santamaria JD et al. 20148 | 58.158 in-hospital mortality rate | ↑ (2.57% vs 1.12%) | p < 0.001 |

| Stowell A. et al. 2013 10 | Mortality rate at 24 h | ↓ (0.00% vs 0.84%) | p < 0.05 |

| Perimal-Lewis L et al. 20139 | In-hospital mortality rate; in-hospital mortality within 48 h | 4.5% vs 3.5% | p = 0.014 |

| 50.4% vs 22.4% | p < 0.001 | ||

| Perimal-Lewis L et al. 2016 (patients with dementia) 6 | In-hospital mortality rate; mortality rate within 48 h; odds ratio | ↑ (9.6% vs 7.9%) | p = 0.072 |

| p = 0.000 | |||

| p = 0.012 | |||

| ↑ (3.2% vs 1.16%) | |||

| ↑OR 1.973; 95% CI 1.158–3.359) | |||

| Alameda C. et al. 200913 | In-hospital mortality | ↓ (17% vs 22%) | p = 0.412 |

| b. Length of stay (LOS) | |||

| Author/year | Sample ( n ) and measure | Results (outliers vs non outliers) | p |

| Bai AD et al. 20184 | LOS in days | = (5.31 vs 5.97 days) | p = 0.1119 |

| Stylianou N et al. 20171 | LOS in days | ↑ (7 vs 3 days) | p < 0.001 |

| Serafini F. et al. 20157 | LOS in days | = (9.8 vs 10 in internal medicine wards; 13 for both in geriatric wards) | p not reported |

| Perimal-Lewis et al. 20139 | LOS in hours | ↓ (110.7 h vs 141.9 h) | p < 0.001 |

| Stowell A. et al. 201310 | LOS in days | ↑ (8 vs 7 days) | p = 0.04 |

| Alameda C. et al. 200913 | LOS in days | ↑ (11.8 vs 9.2 days) | p = 0.001 |

| c. Readmissions | |||

| Author/year | Measure | Results (outliers vs non outliers) | p |

| Stylianou et al. 20171 | Odds ratio | ↑ (odds at 30 days at univariate analysis not confirmed by multivariate) | p = 0.09 |

| Serafini F et al. 20157 | Rate at 90 days | ↑ (26.1 vs 14.2%) | p < 0.0001 |

| Perimal-Lewis et al. 20139 | Rate at 7 and 28 days | ↓ 1.2 vs 2% at 7 days | p = 0.003 |

| ↓ 2.1 vs 4.9% at 28 days | p < 0.001 | ||

| Stowell A. et al. 201310 | Rate at 28 days | ↑ (27 vs 17%) | p = 0.008 |

| Alameda et al. 200913 | Rate at 30 days | ↑ (15 vs 10%) | p = 0.234 |

| d. Other indicators | |||

| Author/year | Indicator | Results (outliers vs non outliers) | p |

| Serafini F et al. 2015 7 | Type of patients less allocated off-ward | Respiratory patients | Not applicable |

| Stowell A. et al. 201310 | VTE prophylaxis | 42 vs 52% | p = 0.03 |

| Number of blood and imaging tests (SD) | |||

| 5.13 vs 4.59 | Not reported | ||

| 1.65 vs 1.41 | |||

| Perimal-Lewis et al. 20139 | ER length of stay | 6.3 vs 5.3 h | p < 0.001 |

| Discharge summary completion within 2 days | 40.7 vs 61.2% | p < 0.001 | |

| Discharge summary completion within 7 days | 64.3% vs 78% | p < 0.001 | |

| Creamer et al. 201011 | Mean consultation time | 152″ vs 136″ | Not reported |

| 25″ vs 14″ | |||

| Mean discussion time | 18% | ||

| Time spent to traveling between wards | |||

| Alameda et al. 2009 13 | In-hospital morbidity* | 24% vs 18% | p = 0.254 |

| Ashdown et al. 200317 | Rate of canceled surgeries | 14.8% | Not applicable |

| Santamaria JD et al. 20148 | % calls to in-hospital emergency team | ↑ by 53% | p < 0.001 |

| Warne S et al. 201012 | Rate of not administered medications in surgical wards | ↑ (100% vs 74%) | p < 0.001 |

| e. Perceived quality and safety of care | |||

| Author/year | Indicator | Results (outliers vs non outliers) | p |

| Goulding L. et al. 2012–2015 (2, 3) | NA (qualitative study) | Patients and health operators reported many safety threats in outliers | Not applicable |

| f. Safety issues | |||

| Author/year | Safety issues | ||

| Rae B. et al. 200716 | Staff factors: too many consultants—large variation in clinical practice | ||

| Process factors within the control of the service: adverse events; ward rounds miss patients; patients not seen at weekends; lack of communication across disciplines; lack of a diagnosis; all diagnoses not dealt with from the start of the admission; too many patients under a single team; interrupted ward rounds by being paged for non-urgent requests. | |||

| Lepage B et al. 20095 | Emergency department care | ||

| Nurse responsible for finding beds for outlying patients not available | |||

| Inaccurate or out-of-date information about bed occupancy in the hospital | |||

| Best compromise between outlier’s pathology and outlying ward’s specialty not taken into account at disposal decision time | |||

| Outlying ward contact, called by emergency department before transfer agreement, varying from ward to ward (duty doctor, charge nurse, nurse) | |||

| Person in charge of admission agreement in outlying ward not contactable | |||

| Wrong information given to outlying wards about outlying patients | |||

| Emergency department contact for outlying patients not known by outlying wards or appropriate specialty wards | |||

| Appropriate specialty staff not informed of hospitalization of outliers who should be in their charge | |||

| Transfer from emergency department to outlying ward | |||

| Final diagnosis or final clinical assessment not made in emergency department, potentially resulting in transfer of patients in unstable condition; emergency department porters not available for patient transfer; bad communication between emergency department and outlying wards about time of transfer; bad communication between emergency department and porters regarding name of outlying ward; patient transferred to outlying ward without medical record | |||

| First day of hospital care | |||

| Final diagnosis or final clinical assessment not entered into emergency department medical record | |||

| Medical or nursing records varying from department to department | |||

| No medical record used for outlying patients | |||

| Bed not yet available at time of admission to outlying ward | |||

| Delayed admission of patients scheduled for non-urgent problems or elective procedures | |||

| Doctors in outlying wards not aware of new outliers hospitalized in their wards | |||

| No defined contact in outlying wards (nurse, charge nurse, or doctor) to call a specialist doctor in appropriate specialty ward | |||

| No traceability of calls from outlying wards to specialist doctors; in appropriate specialty wards, no identification of specialist doctors responsible for care of outlying patients falling within their sphere of competence | |||

| Specialist doctor in appropriate ward not easily contactable; lack of information or prescription from a specialist doctor in appropriate ward to nurses and doctors in outlying ward; no specialist medical and nursing care; diagnostic tests not ordered by a doctor from appropriate specialty; no specialist interpretation of diagnostic tests performed on outlying patients; no specialist information given to outlying patients and their families; no systematic meeting or information transmission between doctors in outlying wards and doctors in appropriate specialty wards; inappropriate nursing care provided to outlying patients | |||

| Care in outlying ward from the second day of hospitalization until the day before discharge | |||

| No specialist follow-up; results of diagnostic tests not systematically transmitted to a specialist doctor in appropriate ward; no specialist information given to outlying patients and their families | |||

| Day of discharge | |||

| Information about discharge and follow-up of outlying patients not given by a specialist doctor from the appropriate ward | |||

| Information in medical record and discharge documents not completed by a specialist doctor from the appropriate ward | |||

| Transport forms and prescriptions not completed by a specialist doctor from the appropriate ward | |||

| Follow-up of outlying patients not scheduled by specialist doctors from appropriate wards | |||

| g. Solutions | |||

| Author/year | Solutions | Results | p |

| Novati R. et al. 20175 | Algorithm supporting rational outward allocation of patients and difficult discharges | Outlier days fell from 6.3 to 5.4% | p = 0.000 |

| Lepage B et al. 200914 | Identification of medical doctor and nurse coordinator for outliers, use of standardized medical records | Not reported | Not applicable |

| Gilligan S et al. 200716 | “Physician of the week”, discharge facilitator, “quick and sick” ward | Reduction of Hospital-Standardized Mortality Rate (HSMR) | Not reported |

| Rae B. et al. 200715 | Discharge planning, increase of transfers from general internal medicine to geriatrics, implementation of a consultant-led ward round 7 days a week | Outlier bed crises solved | Not applicable |

*Intra-hospital infection (urinary, respiratory, bacteremia, or others beginning 48 h after admission), intra-hospital hemorrhage (digestive, urinary, or others), and intra-hospital venous thromboembolism

-

Mortality

The impact of outlier status on in-hospital mortality was reported in eight studies. Perimal-Lewis et al.9 found that being an outlier patient increases the risk-adjusted risk of in-hospital mortality by over 40% (50% of deaths happened in the first 48 h after admission). Bai et al.4 reported similar findings: the risk of in-hospital mortality was three times higher among “bed-spaced patients” in the first week just when patients need more interventions. They also suggested several possible reasons for this: less patient contact with physicians on the clinically appropriate ward; inadequate communication between physicians and host-allied health team members; different skills and experience of the allied health team on host ward. Santamaria et al.8 reported a mortality increase among outliers in general and Perimal-Lewis et al.6 among outliers affected by dementia. These data were refuted by Stowell et al.10 and by Stylianou et al.1 on large numbers (over 70,000 admissions in 3 years of observation) and by Alameda et al.13 among outliers with heart failure. Stowell et al.10 and Stylianou et al.1 examined also 30-day mortality without finding any increase; Perimal et al.6, 9 instead revealed a nonsignificant increase in outliers. Serafini et al.7 investigated 3828 consecutive patients hospitalized in medicine and geriatrics in 2012 and, after adjustment for age and sex, the risk of death was about twice as high for outlier patients admitted to surgical area versus the medical one (hazard ratio 1.8, 95% CI 1.2–2.5).

-

Length of stay (LOS)

LOS was explored in seven studies. Stowell et al.10 and Stylianou et al.1 found a longer LOS among outlier patients (8 vs 7 days and 7 vs 3 days, respectively), consistent with findings by Alameda et al.13 among outliers affected by heart failure (11.8 vs 9.2 days). Perimal-Lewis et al.9 registered a significantly shorter length of stay among outliers (110.7 h vs 141.9 h). No difference was found by Serafini et al.,7 either for medicine or geriatrics (10 vs 9.8 days and 13 days for both, respectively) or by Bai et al. (5.31 vs 5.97 days; p = 0.1119).4

-

Readmissions

Readmissions have been studied by five studies;1, 6, 7, 9, 10, 13 Perimal9 reported that readmission rates within 7 or 28 days were substantially lower in the outlier group (2.1 vs 1.2% and 2.1% vs 4.9%). Alameda13 found an insignificant increase in readmissions with the same DRG at 30 days among outliers affected by heart failure (15% vs 10%). While a univariate analysis suggested increased hospital admissions, adjustment for various patient characteristics found that outlier status did not affect readmission.1 On the other hand, two studies found increased readmission rates;7, 10 the latter found this to be true in both geriatric (29.9% vs 7.2%, p < 0.0001) and general medicine patients (23.7% vs 16.3%, p = 0.01).

-

Other indicators

Additional investigated variables include rates of VTE prophylaxis and test ordering, finding that outliers had lower rates of VTE prophylaxis,10 though no difference in blood or imaging tests.

ED stay was longer in patients eventually admitted to outlying wards;6 respiratory patients were less likely to be outliers than other diseases.7

One study11 found that the “time burden” from visiting patients on outlying wards was significant, nearly doubling the total time spent with patients, though most of this was due to travel time. In addition to taking more time, another study found that elective operations were reduced by almost 15% in presence of outliers boarding on the surgical wards. Another study13 measured a composite outcome, called “in-hospital morbidity” (intra-hospital infection (urinary, respiratory, bacteremia, or others beginning 48 h after admission), intra-hospital hemorrhages (digestive, urinary, or others), and intra-hospital venous thromboembolism). Anyway, in-hospital morbidity was found not statistically different between outliers and inliers (24% vs 18%, p = 0.254).

On the other hand, outliers were more likely to miss medications12 and resulted in increased rates of calls for in-hospital emergency teams.8

-

Perceived quality and safety of care

Goulding et al. explored quality and safety issues from two—the provider and patient—perspectives,2, 3 finding that both groups were worried. Healthcare providers were concerned about five threats to patient safety: (1) increased workload; (2) poor communication between the two wards; (3) less experience about these patients on clinically inappropriate wards; (4) unsuitable ward environment; (5) characteristics of outlying patients. In addition, patients on inappropriate wards may be perceived as less important and moving patients between wards could disorient older and cognitively impaired patients.3 Patients were worried about not belonging, possible communication deficiencies, medical staff availability, nurses’ experience, and resource availability.2

-

Safety issues and solutions

Four studies evaluated the impact of organizational changes on outliers’ risks. One study15 suggested solutions such as active discharge planning from the admission, increase of transfers from general internal medicine to geriatrics in another building, and implementation of a consultant-led ward round 7 days a week. Another study instituted a “physician of the week”16 to review outlying patients and improve continuity of care, and added a discharge facilitator and a short stay ward for patients and acutely unstable patients who required a high level of medical care. The study by Lepage et al.14 identified five domains of potential failure in the management of outliers: care in emergency department, transfer to the outlying wards, first day of hospital care, care from second day to discharge, day of discharge. They then implemented the following solutions: a doctor, in the clinically appropriate wards, who is in charge of outlying patients each day, a nurse coordinator who facilitates communication between the emergency department, specialty wards, and outlying wards and ensure that the location of outlying patients is known and their medical needs adequately coordinated, and standardized medical records in order to ease the transfer of information between departments and aid health professionals.

Novati et al.5 significantly reduced outliers (from 6.3 to 5.4%) by implementing an algorithm, supporting rational outward allocation of patients and difficult discharges.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review on outliers on medicine wards. The literature suggests a possible trend towards increased mortality and hospital readmissions among outliers, though the data was too heterogeneous to pool. The majority of the studies4, 6–9 found a significant increase of in-hospital mortality rate or risk, especially in the first 2 days when patients are medically more active. Data about 30- or 90-day mortality are sparse. Readmissions were evaluated at different intervals (from 7 to 90 days after discharge) in the collected studies. Three out of five documented a larger proportion of 28-day readmissions among outliers; the fourth study documented an increased risk of readmission, but only at univariate analysis. Data about length of stay (LOS) were too inconsistent across the studies to reach any meaningful conclusions.

In addition to being too heterogeneous for pooling, most of the study designs among the included papers were poor, mainly monocentric, retrospective, based on administrative data, and underpowered.1, 13 On the other hand, the inconsistency of results can be due also to different contexts. For example, the habit of moving stable patients outside to admit unstable ones or planning early the discharge, different availability of community facilities, health services, and social support can contribute to discordance. Nevertheless, delay between admission and medical evaluation, discontinuity of care, errors or delay in tests request/execution, inadequate communication between ward teams, less familiarity with monitoring and treatment by hosting team, and nosocomial complications can variously affect mortality, length of stay, and readmission rate. Worrisome is the literature that suggests specialized wards lead to better outcomes from some conditions, such as stroke, renal failure, burns, asthma, gastrointestinal bleeding, trauma, and cancer.18–23

Evidence about other indicators such as proportion of elective surgeries canceled,17 thrombo-prophylaxis, in-hospital infections or in-hospital bleedings, number and appropriateness of investigations, calls to intra-hospital emergency team, and missed medications is limited, but there are other possible drawbacks to being boarded. Moving patients has been shown to increase the risk of healthcare-associated infection (HCAI).24

Two studies exploring patient and provider satisfaction both suggest a perception of reduced quality and safety.2, 3 This can be due to travel time, to lack of established relationships between providers and nurses on the outlying wards, and to worry about patients that are not immediately accessible. The hosting nursing team also feels a sense of inadequacy due to less expertise in the management of outlier’s health problems. Patients feel they do not belong to any ward, feel forgotten, are worried about errors due to staff inexperience, miscommunication, or resource unavailability, and dislike transfers between wards.

All suggested solutions5, 14–16 are multi-component as the problem is complex and needs a system approach and have not been rigorously studied, yet. The “best” solutions are likely to be tailored to the specifics of the individual systems.

CONCLUSIONS

Though literature evidence is quite limited and heterogeneous, the outlier status may be associated with worse outcomes. Certainly, patients and health professionals are dissatisfied. The reported solutions are targeted to locally identified problems and have not been rigorously studied.

There is a need to reach a universally accepted definition of outlier, to adequately measure the effect of outlier status on clinical and safety outcomes, and to develop validated tools to analyze and manage a phenomenon that could negatively impact on care and organizational outcomes.

To this aim, FADOI (the Federation of the Associations of Hospital Internists) has planned a multicenter, prospective, well-sized study comparing mortality rate and adverse event rate in outliers and non-outliers, named “Safety Issues and SurvIval For medical Outliers” (SISIFO) study (NCT03651414) that will start at the end of 2018.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Stylianou N, Fackrell R, Vasilakis C. Are medical outliers associated with worse patient outcomes? A retrospective study within a regional NHS hospital using routine data. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015676. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goulding L, Adamson J, Watt I, et al. Lost in hospital: a qualitative interview study that explores the perceptions of NHS inpatients who spent time on clinically inappropriate hospital wards. Health Expect. 2015;18:982–94. doi: 10.1111/hex.12071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goulding L, Adamson J, Watt I, et al. Patient safety in patients who occupy beds on clinically inappropriate wards: a qualitative interview study with NHS staff. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:218–24. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bai AD, Srivastava S, Tomlinson GA, Smith CA, Bell CM, Gill SS. Mortality of hospitalized Internal medicine patients bedspaced to non-internal medicine inpatient units: retrospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27:11–20. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novati R, Papalia R, Peano L, Gorraz A, Artuso L, Canta MG, Del Vescovo G, Galotto C. Effectiveness of an hospital bed management model: results of four years of follow-up. Ann Ig. 2017;29(3):189–196. doi: 10.7416/ai.2017.2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perimal-Lewis L, Bradley C, Hakendorf PH, Whitehead C, Heuzenroeder L, Crotty M. The relationship between in-hospital location and outcomes of care in patients diagnosed with dementia and/or delirium diagnoses: analysis of patient journey. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):190. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0372-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serafini F, Fantin G, Brugiolo R, Lamanna O, Aprile A, Presotto F. Outlier admissions of medical patients: prognostic implications of outlying patients. The experience of the hospital of Mestre. Ital J Med. 2015;9:299–302. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santamaria JD, Tobin AE, Anstey MH, Smith RJ, Reid DA. Do outlier inpatients experience more emergency calls in hospital? An observational cohort study. Med J Aust. 2014;200:45–8. doi: 10.5694/mja12.11680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perimal-Lewis L, Li JY, Hakendorf PH, Ben-Tovim DI, Qin S, Thompson CH. Relationship between in-hospital location and outcomes of care in patients of a large general medical service. Intern Med J. 2013;43(6):712–6. doi: 10.1111/imj.12066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stowell A, Claret PG, Sebbane M, Bobba X, Boyard C, Grandpierre RG, Moreau A, de le Coussaye J-E. Hospital out-lying through lack of beds and its impact on care and patient outcome. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2013;21:17. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-21-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Creamer GL, Dahl A, Perumal D, Tan G, Koea JB. Anatomy of the ward round: the time spent in different activities. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80(12):930–932. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warne S, Endacott R, Ryan H, Chamberlain W, Hendry J, Boulanger C, Donlin N. Non-therapeutic omission of medications in acutely ill patients. Nurs Crit Care. 2010;15(3):112–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2010.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alameda C, Suárez C. Clinical outcomes in medical outliers admitted to hospital with heart failure. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20:764–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lepage B, Robert R, Lebeau M, Aubeneau C, Silvain C, Migeot V. Use of a risk analysis method to improve care management for outlying inpatients in a University hospital. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;8:441–445. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.025742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rae B, Busby W, Millard PH. Fast-tracking acute hospital care--from bed crisis to bed crisis. Aust Health Rev. 2007;31(1):50–62. doi: 10.1071/AH070050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilligan S, Walters M. Quality improvements in hospital flow may lead to a reduction in mortality. Clin Gov Int J. 2007;13(1):26–34. doi: 10.1108/14777270810850607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashdown DA, Williams D, Davenport K, Kirby RM. The impact of medical outliers on elective surgical lists. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2003;85:46–47. doi: 10.1308/14736350360507352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanderson JD, Taylor RF, Pugh S, Vicary FR. Specialized gastrointestinal units for the management of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Postgrad Med J. 1990;66:654–56. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.66.778.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bucknall CE, Robertson C, Moran F, Stevenson RD. Management of asthma in hospital: a prospective audit. Br Med J. 1988;296:1637–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6637.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayor S. Stroke patients prefer care in specialist units. Br Med J. 2005;331:130. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7509.130-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright N, Shapiro LM, Nicholson J. Treatment of renal failure in a non-specialist unit. Br Med J. 1980;281:117–118. doi: 10.1136/bmj.281.6233.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lloyd JM, Elsayed S, Majeed A, Kadambande S, Lewis D, Mothukuri R, Kulkarni R. The practice of out-lying patients is dangerous: a multicentre comparison study of nursing care provided for trauma patients. Injury. 2005;36(6):710–3. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohan S, Wilkes LM, Ogunsiji O, Walker A. Caring for patients with cancer in non-specialist wards: the nurse experience. Eur J Cancer Care. 2005;14:256–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clements A, Halton K, Graves N, Pettitt A, Morton A, Looke D, Whitby M. Overcrowding and understaff- ing in modern health-care systems: key determinants in meticillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus transmission. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:427–434. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70151-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]