Abstract

Semiconductor qubits rely on the control of charge and spin degrees of freedom of electrons or holes confined in quantum dots. They constitute a promising approach to quantum information processing, complementary to superconducting qubits. Here, we demonstrate coherent coupling between a superconducting transmon qubit and a semiconductor double quantum dot (DQD) charge qubit mediated by virtual microwave photon excitations in a tunable high-impedance SQUID array resonator acting as a quantum bus. The transmon-charge qubit coherent coupling rate (~21 MHz) exceeds the linewidth of both the transmon (~0.8 MHz) and the DQD charge qubit (~2.7 MHz). By tuning the qubits into resonance for a controlled amount of time, we observe coherent oscillations between the constituents of this hybrid quantum system. These results enable a new class of experiments exploring the use of two-qubit interactions mediated by microwave photons to create entangled states between semiconductor and superconducting qubits.

Subject terms: Quantum information, Superconducting devices, Qubits

Hybrid quantum devices combine different platforms with the prospect of exploiting the advantages of each. Scarlino et al. demonstrate strong, coherent coupling between a semiconductor qubit and a superconducting qubit by using a high-impedance superconducting resonator as a quantum bus.

Introduction

Single electron spins confined in semiconductor quantum dots (QDs) can preserve their coherence for hundreds of microseconds in 28Si1,2, and have typical relaxation times of seconds3,4. This property can be explored, for example, to build memories for quantum information processors in hybrid architectures combining superconducting qubits and spin qubits. Typically, semiconductor qubit–qubit coupling is short range, effectively limiting the interqubit distance to the spatial extent of the wavefunction of the confined particle, which is a significant constraint toward scaling to reach dense 1D or 2D arrays of QD qubits. Strategies to interconnect semiconductor qubits include the control of short-range interactions through the direct overlap of electronic wavefunctions5–7, the direct capacitive coupling between QDs8, enhanced by floating metallic gates9, shuttling of electrons between distant QDs by surface acoustic waves10,11, by time-varying gate voltages12 and by fermionic cavities13. An alternative approach which allows for long-range qubit–qubit interaction, inspired by superconducting circuit quantum electro-dynamics (QED)14, and recently explored also for semiconductor QDs15–17, is to use microwave photons confined in superconducting resonators to mediate coupling between distant qubits. In this approach, the microwave resonator not only acts as a quantum bus, but also allows for quantum nondemolition qubit readout18–20.

With the well established strong coupling of superconducting qubits to microwave resonators14 and the recently achieved strong coupling to charge states in semiconductor double dot structures21,22, it is now possible to create a microwave photon-based interface between superconducting and semiconducting qubits mediated by a joint coupling resonator. A similar strategy has been explored in hybrid structures interfacing a transmon qubit with excitations of a spin-ensemble of NV centers in diamonds23–25 and of collective spins (magnons) in ferromagnets26–28. Furthermore, direct coupling between a superconducting flux qubit and an electron spin ensemble in diamond was investigated29. In these works the strong coupling regime was achieved with ensembles, for which the coupling strength scales with the square root of the number of two-level systems interacting with the resonator mode.

Here, we explore the coupling of the charge degree of freedom of a single electron confined in a double QD (DQD) to a superconducting transmon qubit in the circuit QED architecture14. The coherent coupling between dissimilar qubits over a distance of a few hundred micrometers is mediated by virtual microwave photon excitations in a high impedance SQUID array resonator, which acts as a quantum bus. We demonstrate resonant and dispersive interaction between the two qubits mediated by real and virtual photons, respectively. We extract a coupling strength of ~36 MHz (~128 MHz) between the bus resonator and the DQD (transmon) around the frequency of ~3.7 GHz. With a frequency detuning of ~370 MHz from the resonant frequency of the bus resonator, we spectroscopically observe a qubit avoided crossing of about ~21 MHz. The strength of the virtual-photon mediated interaction is extracted from measurements of coherent qubit population oscillations. The methods and techniques presented here have the potential to be transferred to QD devices based on a range of material systems and can be beneficial for spin-based hybrid systems.

Results

Sample design and basic circuit characterization

To perform our experiments, we integrate four different quantum systems into a single device: a semiconductor DQD charge qubit, a superconducting qubit, and two superconducting resonators (see Fig. 1a). One resonator acts as a quantum bus between the superconducting and the semiconductor qubits and the other one as a readout resonator for the superconducting qubit. In this way, the functionality for qubit readout and coupling is implemented using two independent resonators at different frequencies, allowing for more flexibility in the choice of coupling parameters and reducing unwanted dephasing due to residual resonator photon population30. A simplified circuit diagram of the device is shown in Fig. 1f.

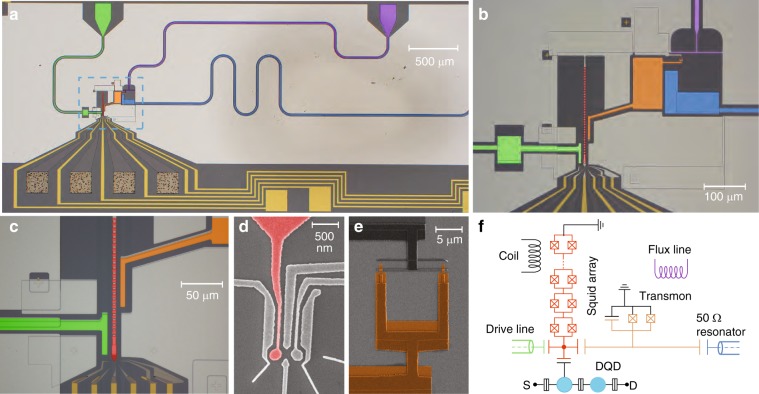

Fig. 1.

Sample and simplified circuit diagram. a False color optical micrograph of the device showing the substrate (dark gray), the Al superconducting structures forming the groud plane (light gray), the DQD Au gate leads (yellow), the SQUID array resonator (red), its microwave feedline (green), the single island transmon (orange), its readout 50 Ω coplanar waveguide resonator (blue), and the flux line (purple). b Enlarged view of the sample area enclosed by the blue dashed line in panel (a). c Enlarged view of the coupling side of the SQUID array. d Electron micrograph of the DQD showing its electrostatic top gates (Al-light gray) and the plunger gate coupled to the SQUID array (red). e Electron micrograph of the transmon SQUID. f Circuit diagram schematically displaying the DQD [with its source (S) and drain (D) contact], capacitively coupled to the SQUID array resonator, which in turn is coupled to the transmon. The transmon and the SQUID array are respectively capacitively coupled to a 50 Ω CPW resonator and microwave feedline. Their resonance frequencies can be tuned by using a flux line and a coil schematically shown in the circuit diagram. The color code is consistent with the optical micrographs

The superconducting qubit is of transmon type and consists of a single superconducting aluminum (Al) island shunted to ground via a SQUID (orange in Fig. 1). The transmon charging and Josephson energies are Ec/h ~243.0 ± 0.2 MHz and , respectively (see Supplementary Note 2 for more information). The transition frequency ωtr between its ground state |g〉 and excited state |e〉 is adjusted by using the magnetic flux generated in the transmon SQUID loop by a flux line (purple in Fig. 1). We read out the state of the transmon qubit with a 50 Ω coplanar waveguide resonator (dark blue in Fig. 1) capacitively coupled to the qubit14,31.

The DQD charge qubit (Fig. 1d), schematically indicated by the two light blue dots in Fig. 1f, is defined by standard depletion gate technology using Al top gates on a GaAs/AlGaAs heterostructure that hosts a two-dimensional electron gas (2DEG)15,21,32. The DQD is tuned to the few-electron regime and its excitation energy is given by , with the inter-dot tunnel rate tc and the DQD energy detuning δ.

We use a superconducting high-impedance resonator for mediating interactions between the transmon and the DQD21. The resonator is composed of an array of 35 SQUIDs (Fig. 1b), and is capacitively coupled to both transmon and DQD charge qubits (see Fig. 1b, f). It is grounded at one end and terminated in a small island at the other end to which a single coplanar drive line is capacitively coupled (green in Fig. 1b, c). A gate line extends from the island and forms one of the plunger gates of the DQD (in red in Fig. 1d)21,32. The high impedance of the resonator increases the strength of the vacuum fluctuations of electric field, enhancing the coupling strength of the individual qubits to the resonator (see Supplementary Note 2 for more information).

We characterize the hybrid circuit by measuring the amplitude and phase change of the reflection coefficient of a coherent tone at frequency ωp reflected from the multiplexed resonators (the microwave setup is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1). The response changes with the potentials applied to the gate electrodes forming the DQD and the magnetic flux applied to the transmon. By varying the DQD detuning δ and the transmon flux Φtr, each qubit is individually tuned into resonance with the high-impedance resonator. The coupling strengths measured between the SQUID array resonator and the DQD charge qubit and the transmon qubit are 2gDQD,Sq/2π ~66.2 ± 0.4 MHz (at ωr,Sq/2π = 4.089 GHz) and 2gtr,Sq/2π ~451.3 ± 0.3 MHz (at ωr,Sq/2π = 5.180 GHz), respectively, for more details see Supplementary Note 5 and Supplementary Fig. 3. For the same configuration, we extract the linewidth of the qubits spectroscopically21,30 and find δωDQD/2π ~2.7 ± 0.4 MHz and δωtr/2π ~0.78 ± 0.05 MHz. Both subsystems individually are in the strong coupling regime (2g > κ/2 + γ2) with a SQUID array resonator linewidth of κ/2π = (κext + κint)/2π ~(3 + 5) MHz.

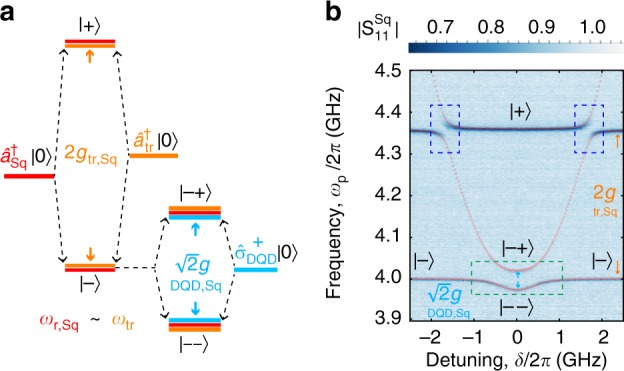

Resonant interaction

To demonstrate the coherent coupling between the transmon qubit and the DQD charge qubit, we first characterize the configuration with the three systems interacting resonantly with each other (see Fig. 2). We tune the SQUID array into resonance with the transmon and observe the vacuum Rabi modes , with the ground state of the system |0〉 = |0〉Sq ⊗ |g〉tr ⊗ |g〉DQD and the creation operators for the excitations in the SQUID array (transmon) (). The mixing angle θm is determined by tan2θm = 2gtr,Sq/|Δtr|, with and the transmon excitation frequency dressed by the interaction with the 50 Ω resonator. We then configure the DQD electrostatic gate voltages to tune its transition frequency at the charge sweet spot [ωDQD(δ = 0) = +2tc] into resonance with the lower transmon-SQUID array Rabi mode |−〉. From the hybridization between the states |−〉 and the DQD excited state , we obtain the states |−−〉 and |−+〉, leading to the avoided crossing enclosed by the green dashed box in Fig. 2b. Similarly, when the DQD excitation energy is equal to the energy of the higher transmon-SQUID array Rabi mode, |+〉, the hybrid system develops two avoided crossings at the respective detunings δ in the spectrum (see blue dashed box in Fig. 2b). The observed spectrum resulting from the hybridization of the three quantum systems is in good agreement with our calculation (see red dots in Fig. 2b and “System Hamiltonian” section in Supplementary Note 2 for more information).

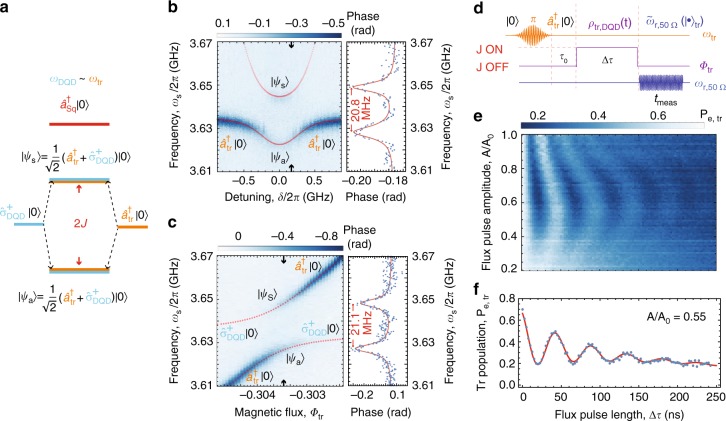

Fig. 2.

Resonant interaction between the DQD charge qubit, the SQUID array resonator and the transmon. a Energy level diagram of the DQD-SQUID array-transmon system for the bias point considered in panel (b). The energy levels are colored in accordance with the code used in Fig. 1. b Reflectance of the SQUID array resonator hybridized with the transmon and DQD as a function of the DQD detuning δ at the bias point discussed in the main text. Red dots are obtained by numerical diagonalization of the system Hamiltonian [see Eq. (1) in Supplementary Note 2], using parameters extracted from independent spectroscopy measurements

Dispersive interaction

Next, we discuss the virtual photon-mediated coherent interaction between the DQD and the transmon qubit. This is realized in the dispersive regime, where both qubit frequencies are detuned from the high-impedance resonator. In this regime, no energy is exchanged between the qubits and the resonator, and the strength of the effective coherent interaction between the two qubits is given by 2J ~gtr,SqgDQD,Sq/(1/|Δtr| + 1/|ΔDQD|)19,20. We spectroscopically explore this qubit–qubit coupling by applying a probe tone at frequency ωp/2π = 6.5064 GHz to the transmon readout resonator. The reflectance of the probe tone from the 50 Ω resonator is measured while a microwave spectroscopy tone of frequency ωs is swept across the transmon transition frequency to probe its excitation spectrum30.

To observe the coherent DQD-transmon coupling, we either tune δ to bring the DQD into resonance with the transmon (see Fig. 3b) or tune Φtr to bring the transmon into resonance with the DQD (see Fig. 3c). In either case, when the qubit frequencies are in resonance, as depicted in Fig. 3a, a clear avoided crossing of magnitude 2J/2π ~21.1 ± 0.2 MHz (Fig. 3c), larger than the combined linewidth of the coupled system (γDQD + γtr)/2π ~4.6 ± 0.5 MHz, is observed. The observed resonance frequencies are in good agreement with our simulation (red dots in Fig. 3b, c) for the explored configuration characterized by |ΔDQD| ~10gDQD,Sq and |Δtr| ~3gtr,Sq. The well-resolved DQD-transmon avoided crossing demonstrates that the high-impedance resonator mediates the coupling between the semiconductor and the superconducting qubit.

Fig. 3.

DQD-transmon interaction mediated by virtual photon exchange in the SQUID array resonator. a Energy level diagram of the DQD-transmon qubit coupling mediated via dispersive interaction with the SQUID array resonator (red line). The DQD excitation , the transmon excitation and the SQUID array resonator excitation are shown, together with their hybridized states |Ψs,a〉 and the system vacuum state |0〉 = |0〉Sq ⊗ |g〉tr ⊗ |g〉DQD. b Left: spectroscopy of the DQD qubit interacting with the transmon. Phase Δϕ = Arg[S11] of a fixed frequency measurement tone ωp/2π = 6.5064 GHz = ωr,50Ω/2π reflected off the 50 Ω CPW read-out resonator vs. transmon qubit spectroscopy frequency ωs and DQD qubit detuning δ [(c) the flux through the SQUID loop of the transmon Φtr]. Right: phase Δϕ = Arg[S11] response at the DQD detuning δ [(c) at the flux Φtr] indicated by the black arrows in left panel showing a coupling splitting of 2J ~20.8 ± 0.3 MHz [2J ~21.1 ± 0.2 MHz]. d Pulse protocol for the population transfer between the transmon and the DQD charge qubit. ρ(t) indicates the density matrix of the coupled transmon-DQD system during the interaction time Δτ and . τ0 is a finite time difference between the preparation pulse and the flux pulse. e Average transmon excited state population Pe,tr (each data point is the intergrated average over 50,000 repetitions of the experiment), as a function of the flux pulse length Δτ and normalized flux pulse amplitude A/A0. f Transmon excited state population Pe,tr vs. Δτ for a flux pulse amplitude of A/A0 = 0.55, for which the transmon is approximately in resonance with the DQD (ωtr/2π ~ωDQD/2π=3.660 GHz). ωr,Sq/2π = 4.060GHz and ωr,50Ω/2π = 6.5048 GHz. The red line is a fit to a Markovian master equation model (see Supplementary Note 6 for more details)

Time-resolved population transfer oscillations

We demonstrate virtual-photon mediated coherent population transfer between the transmon and DQD charge qubits in time-resolved measurements. We induce the exchange coupling by keeping the DQD and SQUID array cavity frequencies fixed at ωDQD(δ = 0)/2π = 3.66 GHz and ωr,Sq/2π = 4.06 GHz, respectively, and varying the transmon frequency nonadiabatically18,19 using the pulse protocol illustrated in Fig. 3d. Initially, both qubits are in their ground state and the effective coupling between them is negligible, due to the large difference between their excitation frequencies. Next, we apply a π-pulse to the transmon qubit to prepare it in its excited state . Then, a nonadiabatic current pulse, applied to the flux line, changes the flux Φtr and tunes the transmon into resonance with the DQD charge qubit for a time Δτ, which we vary between 0 and 250 ns. After the completion of the flux pulse controlling the interaction, the state of the transmon is measured (for a time tmeas) through its dispersive interaction with the 50 Ω CPW resonator. We observe coherent oscillations of the transmon excited state population as a function of the interaction time Δτ (see Fig. 3e, f).

The population oscillations during the time Δτ are caused by the exchange interaction with coupling strength J(|Δtr|, |ΔDQD|). Oscillations in both the transmon population and in the DQD occur as the excitation is transferred between the two, Fig. 3e. Due to energy relaxation and dephasing of both systems, the population oscillations are damped and the mean population decays over time. In the current experiment, we were able to only extract the transmon population. Future experiments may allow to also measure the DQD population and to explore the correlations between the two qubits to explicitly verify the entanglement of the two systems. As a result, we observe the characteristic chevron pattern in the transmon qubit population in dependence on the flux pulse amplitude and length (see Fig. 3e)18.

A trace of the population oscillation pattern at fixed pulse amplitude , approximately realizing the DQD-transmon resonance condition (), is in excellent agreement with the Markovian master equation simulation (see the red line in Fig. 3f and Supplementary Note 6 for more information). The simulations are performed within the dispersive approximation in which the qubits interact with rate 2J/2π = 21.8 ± 0.1 MHz, via an exchange interaction consistent with the spectroscopically measured energy splitting 2J/2π ~21.1 ± 0.2 MHz (Fig. 3c).

Discussion

Further improvements in device design and sample parameters could allow to increase the visibility and fidelity of the coherent population transfer protocol between the two different quantum computing platforms. By increasing the bus resonator impedance even further, e.g., by making use of a Josephson junction array (instead of a SQUID array), it will be possible to increase the coupling strength of the artificial atoms with the radiation field by about a factor of two. This will allow also to increase the frequency detuning between the qubits and the quantum bus, which will result in a reduction of the relaxation rate of the transmon, limited by Purcell decay in the current experiment. This can be also achieved by reducing the ktot of the bus resonator or realizing a Purcell filter33. Furthermore, the realization of the superconducting elements on a more suitable substrate, such as sapphire or silicon, could allow to further reduce the intrinsic loss of the transmon and of the high impedance resonator while maintaining the possibility to capacitively couple to the DQD structure, making use of flip-chip technology34. From the semiconductor qubit side, moving to silicon as host material could allow to reach a longer coherence time for both the charge and the spin degrees of freedom of the confined electron.

In this work, we realized an interface between semiconductor- and superconductor-based qubits by exchanging virtual photons between two distinct physical systems in a hybrid circuit QED architecture35,36. The coherent interaction between the qubits is witnessed both by measurements of well-resolved spectroscopic level splitting and by time-resolved population oscillations. The interaction can be enabled both electrically via the QD and magnetically via the transmon qubit. The resonator mediated coupling also provides for nonlocal coupling to the semiconductor qubit, demonstrated here over distances of more than 50 μm. We expect the approach demonstrated here for the charge degree of freedom of a semiconductor qubit to be transferable to the spin degree of freedom and also to other material systems such as Si or SiGe37–39. In this way, the coupling to electron spin or even nuclear spin qubits may provide an avenue for realizing a spin based quantum memory, which can be interfaced to other solid state qubits, including superconducting ones. In addition, the combination of short distance coupling and control in semiconductor qubits with long-distance coupling through microwave resonators provided by circuit QED may indicate a viable solution to the wiring and coupling challenge in semiconductor qubits40 and may be essential for realizing error correction in these systems, for example by using the surface code41.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Michele Collodo, Johannes Heinsoo, Philipp Kurpiers, Agustin Di Paolo, and Simon Storz for helpful discussions and for valuable contributions to the experimental setup, software, and numerical simulations. This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF) through the National Center of Competence in Research (NCCR) Quantum Science and Technology (QSIT), the project Elements for Quantum Information Processing with Semiconductor/Superconductor Hybrids (EQUIPS) and by ETH Zurich. U.C.M. and A.B. were supported by NSERC and the Canada First Research Excellence fund.

Author contributions

P.S. designed the sample with the inputs from S.G., D.J.v.W., and A.W.. P.S., D.J.v.W., J.V.K., and A.J.L. fabricated the device. D.J.v.W. and P.S. performed the experiments. P.S. and D.J.v.W. analyzed the data. U.C.M., C.K.A., and A.B. performed the theoretical simulations. C.R. and W.W. provided the heterostructure. P.S., U.C.M., and A.W. wrote the paper with the input of all authors. A.W., K.E., and T.I. coordinated the project.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this letter and corresponding Supplementary Information file are available online at the ETH Zurich repository for research data https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000347083.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: P. Scarlino, D.J. van Woerkom.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-10798-6.

References

- 1.Muhonen JT, et al. Storing quantum information for 30 s in a nanoelectronic device. Nat. Nano. 2014;9:986–991. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veldhorst M, et al. An addressable quantum dot qubit with fault-tolerant control-fidelity. Nat. Nano. 2014;9:981–985. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watson TF, et al. Atomically engineered electron spin lifetimes of 30 s in silicon. Sci. Adv. 2017;3:e1602811. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1602811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morello A, et al. Single-shot readout of an electron spin in silicon. Nature. 2010;467:687–691. doi: 10.1038/nature09392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nowack KC, et al. Single-shot correlations and two-qubit gate of solid-state spins. Science. 2011;333:1269–1272. doi: 10.1126/science.1209524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veldhorst M, et al. A two-qubit logic gate in silicon. Nature. 2015;526:410–414. doi: 10.1038/nature15263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watson TF, et al. A programmable two-qubit quantum processor in silicon. Nature. 2018;555:633–637. doi: 10.1038/nature25766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shulman MD, et al. Demonstration of entanglement of electrostatically coupled singlet-triplet qubits. Science. 2012;336:202–205. doi: 10.1126/science.1217692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trifunovic L, et al. Long-distance spin-spin coupling via floating gates. Phys. Rev. X. 2012;2:011006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNeil R, et al. On-demand single-electron transfer between distant quantum dots. Nature. 2011;477:439–442. doi: 10.1038/nature10444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hermelin S, et al. Electrons surfing on a sound wave as a platform for quantum optics with flying electrons. Nature. 2011;477:435–438. doi: 10.1038/nature10416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baart TA, Jovanovic N, Reichl C, Wegscheider W, Vandersypen LMK. Nanosecond-timescale spin transfer using individual electrons in a quadruple-quantum-dot device. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016;109:043101. doi: 10.1063/1.4959183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicol G, et al. Cavity-mediated coherent coupling between distant quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018;120:236801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.236801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallraff A, et al. Strong coupling of a single photon to a superconducting qubit using circuit quantum electrodynamics. Nature. 2004;431:162–167. doi: 10.1038/nature02851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frey T, et al. Dipole coupling of a double quantum dot to a microwave resonator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;108:046807. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.046807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petersson KD, et al. Circuit quantum electrodynamics with a spin qubit. Nature. 2012;490:380–383. doi: 10.1038/nature11559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delbecq MR, et al. Coupling a quantum dot, fermionic leads, and a microwave cavity on a chip. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011;107:256804. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.256804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blais A, et al. Quantum-information processing with circuit quantum electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. A. 2007;75:032329. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.75.032329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majer J, et al. Coupling superconducting qubits via a cavity bus. Nature. 2007;449:443–447. doi: 10.1038/nature06184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sillanpää MA, Park JI, Simmonds RW. Coherent quantum state storage and transfer between two phase qubits via a resonant cavity. Nature. 2007;449:438–442. doi: 10.1038/nature06124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stockklauser A, et al. Strong coupling cavity QED with gate-defined double quantum dots enabled by a high impedance resonator. Phys. Rev. X. 2017;7:011030. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mi X, Cady JV, Zajac DM, Deelman PW, Petta JR. Strong coupling of a single electron in silicon to a microwave photon. Science. 2017;355:156–158. doi: 10.1126/science.aal2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kubo Y, et al. Hybrid quantum circuit with a superconducting qubit coupled to a spin ensemble. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011;107:220501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.220501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kubo Y, et al. Electron spin resonance detected by a superconducting qubit. Phys. Rev. B. 2012;86:064514. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.86.064514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grezes C, et al. Multimode storage and retrieval of microwave fields in a spin ensemble. Phys. Rev. X. 2014;4:021049. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tabuchi Y, et al. Coherent coupling between a ferromagnetic magnon and a superconducting qubit. Science. 2015;349:405–408. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tabuchi Y, et al. Quantum magnonics: the magnon meets the superconducting qubit. Comptes Rendus Phys. 2016;17:729–739. doi: 10.1016/j.crhy.2016.07.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lachance-Quirion D, et al. Resolving quanta of collective spin excitations in a millimeter-sized ferromagnet. Sci. Adv. 2017;3:e1603150. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1603150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu X, et al. Coherent coupling of a superconducting flux qubit to an electron spin ensemble in diamond. Nature. 2011;478:221–224. doi: 10.1038/nature10462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuster DI, et al. AC Stark shift and dephasing of a superconducting qubit strongly coupled to a cavity field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005;94:123602. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.123602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallraff A, et al. Approaching unit visibility for control of a superconducting qubit with dispersive readout. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005;95:060501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.060501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scarlino, P. et al. All-microwave control and dispersive readout of gate-defined quantum dot qubits in circuit quantum electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 206802 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Reed MD, et al. Fast reset and suppressing spontaneous emission of a superconducting qubit. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010;96:203110. doi: 10.1063/1.3435463. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Brien, W. et al. Superconducting caps for quantum integrated circuits. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1708.02219 (2017).

- 35.Xiang Z-L, Ashhab S, You JQ, Nori F. Hybrid quantum circuits: superconducting circuits interacting with other quantum systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2013;85:623–653. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.85.623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurizki G, et al. Quantum technologies with hybrid systems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2015;112:3866–3873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419326112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mi X, et al. A coherent spin-photon interface in silicon. Nature. 2018;555:599–603. doi: 10.1038/nature25769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Landig AJ, et al. Coherent spin-photon coupling using a resonant exchange qubit. Nature. 2018;560:179–184. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0365-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samkharadze N, et al. Strong spin-photon coupling in silicon. Science. 2018;359:1123–1127. doi: 10.1126/science.aar4054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vandersypen LMK, et al. Interfacing spin qubits in quantum dots and donors—hot, dense, and coherent. npj Quantum Inf. 2017;3:34. doi: 10.1038/s41534-017-0038-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fowler AG, Mariantoni M, Martinis JM, Cleland AN. Surface codes: towards practical large-scale quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A. 2012;86:032324. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.86.032324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this letter and corresponding Supplementary Information file are available online at the ETH Zurich repository for research data https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000347083.