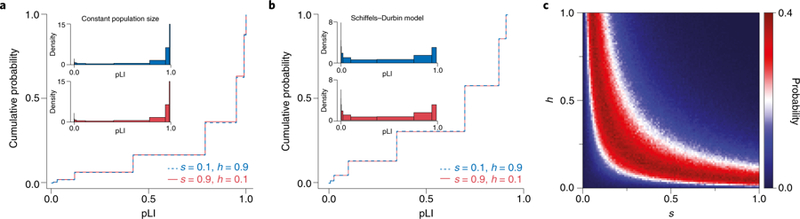

Figure 1. pLI relates to hs, but not h and s separately.

(A & B) Different combinations of h and s with the same hs value yield highly similar distributions of pLI. We considered PTVs arising in a hypothetical human gene of typical length for (A) a population of constant size and (B) a plausible model of changes in the effective population size of Europeans over time47. We modeled the distinct number of segregating PTVs in a population using forward simulations (see Supplementary Note for details). We first obtained the number of PTVs expected under neutrality by averaging over 106 simulations with s=h=0. Then, for different combinations of s and h, we calculated the pLI value for each replicate from the number of PTVs obtained. The lines show the cumulative distribution of pLI in 106 replicates for the parameter combinations of s=0.1,h=0.9 (blue, dashed) and s=0.9,h=0.1 (red, solid). The insets in each figure show the density of the distribution of pLI scores. (C) The probability of observing a specific PTV count is maximized along a ridge of fixed hs. We generated the distribution of PTV counts in a hypothetical human gene under the Schiffels-Durbin model as above for a grid of s and h values, using 106 replicates for each parameter combination. The figure depicts the likelihood of observing a PTV count of 3 (the value that by chance was obtained in the first run of s=0.10,h=0.90 and was treated as observed) for each combination of h and s.