Abstract

Objective

The aims of this paper were to identify, characterise and explain clinician factors that shape decision-making around antidepressant discontinuation in UK primary care.

Design

Four focus groups and three interviews were conducted and analysed using thematic analysis.

Participants

Twenty-one general practitioners (GPs), four GP assistants, seven nurses and six community mental health team workers and psychotherapists took part in focus groups and interviews.

Setting

Participants were recruited from seven primary care regions and two National Health Service Trusts providing community mental health services in the South of England.

Results

Participants highlighted a number of barriers and enablers to discussing discontinuation with patients. They held a range of views around responsibility, with some suggesting it was the responsibility of the health professional (HP) to broach the subject, and others suggesting responsibility rested with the patients. HPs were concerned about destabilising the current situation, discussed how continuity and knowing the patient facilitated discontinuation talks, and discussed how confidence in their professional skills and knowledge affected whether they elected to raise discontinuation in consultations.

Conclusions

Findings indicate a need to consider support for HPs in the management of antidepressant medication and discussions of discontinuation in particular. They may also benefit from support around their fears of patient relapse and awareness of when and how to initiate discussions about discontinuation with their patients.

Keywords: antidepressants, primary care, health professional

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study explored the views of primary care health professionals (HPs) in relation to antidepressant withdrawal.

Focus groups allowed participants to exchange views on the topic thereby providing topic-rich data.

Unlike previous research, this study included perspectives of non-general practitioner HPs.

The use of focus groups facilitated group discussion; however, it is possible that the group setting may reduce openness.

Introduction

Antidepressant prescriptions have risen steadily since the introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in the late 1980s. This rise is primarily due to general practitioners (GPs) continuing to prescribe for longer,1 2 with the average length of treatment now at more than 2 years.3 4 Around 10% of adults are currently taking antidepressants (predominantly for depression, but also for anxiety and chronic pain).5 Some people need long-term antidepressants to prevent relapse, but surveys suggest 30%–50% have no guideline-based indication for long-term use (eg, according to National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Depression Guideline (2009)).6–8 This may be due to many patients on long-term treatment being given repeat prescriptions and being reviewed infrequently.9 10

The side effects of antidepressants include weight gain, sexual dysfunction, sleep disturbance and gastrointestinal bleeding, which increase with longer term use.11 SSRI use for depression in older patients is associated with increased risk of falls, fractures, seizures, stroke and hyponatraemia.12 Long-term treatment may lead to emotional blunting,13 impaired self-confidence and increased dependence on health services. Antidepressants constitute a substantial proportion of the National Health Service (NHS) drug budget: 2.5% in 201014 and the costs of unnecessary treatment include appointments for medical or nursing reviews. The cost of GP consultations for depression exceeded £30 million in 2008, in addition to the cost of the 64.7 million antidepressant prescriptions of around £266 million.15–17 Attempts to discontinue in the 30%–50% of patients taking antidepressants without guidance-based indication may then result in reduced NHS costs while alleviating the side effects associated with antidepressant use.

Prompting GPs to review patients eligible for withdrawal was tested in a trial in the Netherlands and found to be ineffective, with 6% of patients discontinuing antidepressants in the intervention group and 8% in the control group.18 Similarly, an uncontrolled trial of pharmacist-prompted GP review of long-term users in Scotland resulted in only 7% of people stopping.3 Prompting alone is therefore insufficient in supporting patients to discontinue antidepressants, which indicates there are other factors preventing GPs from attempting to withdraw patients from antidepressants.

While GPs play a key role in prescribing and discontinuing antidepressants, other health professionals (HPs) also advise patients about antidepressants in primary care. Previous research with HPs looking at antidepressant discontinuation has reported that the main barrier is a lack of awareness of guidance on best practice in discontinuation.19 Other barriers include a lack of awareness of patient expectations that HPs should initiate discussions of discontinuation, the availability of alternative treatments, time constraints, and GP and patient fear of destabilising a currently well patient.19 20 Further to this, patients may experience withdrawal symptoms or relapse and require further treatment from their practitioner.21 A qualitative metasynthesis of patient and practitioner’s perspectives on antidepressant discontinuation highlighted a lack of consistent support and guidance for GPs and the impact of time constraints on discontinuation.22 However, there is only limited evidence on the HP’s perspective of antidepressant discontinuation (in particular practice nurses and community mental health workers), and previous studies were completed outside of the UK, and one within a nursing home. Insights into UK primary care HP’s perspectives are therefore needed to determine barriers and facilitators to supporting patients in discontinuing antidepressants in the UK.

The REviewing long term anti-Depressant Use by Careful monitoring in Everyday practice (REDUCE) programme aims to identify ways of helping patients taking long-term antidepressants withdraw from treatment when appropriate.23 Normalisation Process Theory (NPT) identifies, characterises and explains key mechanisms that motivate and shape implementation processes.24 It focuses attention on the work that participants in these processes do when they seek to routinely incorporate components of complex interventions in their everyday lives. This paper reports the findings from the HP focus groups as part of the REDUCE programme. Our aims were to identify, characterise and explain clinician factors that shape decision-making around antidepressant discontinuation in UK primary care.

Methods

Participants

HPs including GPs, GP assistants, nurses, community mental health team workers and psychotherapists were recruited from seven primary care regions and two NHS Trusts providing community mental health services in the South of England between January and May 2017. GP practices and individuals were recruited via email and were invited to return a reply slip. HPs who expressed an interest were invited to take part in one of four focus groups taking place in the South of England between March and May 2017. Twenty-one sites returned a reply slip, with 38 participants taking part in either a focus group or interview (22 females, 12 males, and four participants for whom demographic information was not provided). The reported range of years since qualified was 8–34. Focus groups were chosen over individual interviews to allow participants to exchange views on the topic thereby providing topic rich data as well as an insight into group and individual views, including important areas of consensus and disagreement. Individual interviews were offered to psychotherapists as this group was under-represented in the focus group sample (n=2) and to one GP in order to pilot the topic guide. Every participant was taken through the informed consent process and given the opportunity to read the information leaflet and ask questions prior to data collection. Each focus group had between 7 and 10 participants, and the length of each ranged between 43 and 59 min.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public members of the REDUCE team were involved in discussions about the design and recruitment for this study, and were invited to comment on initial drafts of the topic guide.

Focus groups

A topic guide was developed based on the main aims of the study (online supplement 1). This guide was developed based on a review of existing literature and discussion within a team of academics, GPs, psychiatrists and patient contributors. Topics explored long-term antidepressant use and knowing when discontinuation may be appropriate, negotiating the decision to discontinue antidepressants with patients, HP roles in supporting and negotiating appropriateness of discontinuation, optimising discussions about possible discontinuation and optimising implementation of a discontinuation intervention in routine practice. NPT24 informed the topic guide so that the questions addressed the processes involved in antidepressant discontinuation with regard to the four NPT constructs (coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring). For example, to address cognitive participation (ie, who does the work), participants were asked ‘What do you see as your role in negotiating medication discontinuation’. The topic guide was not limited to discussing depressive disorders and therefore was open to discussion about antidepressant use in other conditions (eg, anxiety and chronic pain).

bmjopen-2018-027837supp001.pdf (218.4KB, pdf)

The focus groups were conducted face-to-face and were organised pragmatically across different geographical locations (in GP practices and a community-based health centre) in the South of England. Two groups were held with mixed primary care HPs and two groups with GPs only (see table 1). To acknowledge potential ‘group’ effects (ie, participants being unaware of the degree to which other group members’ views represent their own experience), free participation was encouraged by the facilitators by avoiding censorship and conformity.25 Focus groups were facilitated by two experienced female qualitative researchers (SJW and WOB) and were audio recorded. A debriefing was conducted by the two facilitators following each focus group to identify issues that may affect analysis (eg, domineering or quiet members) and suggest possible modifications to the topic guide. No repeat interviews or focus groups were conducted.

Table 1.

Number of health professionals attending each focus group or interview

| Focus group 1 | Focus group 2 | Focus group 3 | Focus group 4 | Interview | Total (n female) | |

| GP | 7 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 21 (10) |

| GPA | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (3) |

| NP | 0 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 7 (6) |

| CMHW or PT | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 6 (3) |

| Total | 7 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 3 | 38 |

CMHW, community mental health team worker; GP, general practitioner; GPA, general practitioner assistant; NP, nurse practitioner; PT, psychological therapist.

Interviews

Three semistructured face-to-face qualitative interviews were conducted with two psychotherapists and a GP. The same topic guide that had been developed for the focus groups was used in the interviews to ensure consistency. As with the focus groups, the interviewer explored additional topics when brought up by the interviewee. Interviews were carried out by an experienced qualitative researcher (SJW) and were audio recorded.

Analysis

All focus groups and interviews were transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were read and re-read by SJW both during and after the data collection period. While the focus groups and interviews were taking place, the REDUCE Study team met regularly to discuss topics raised by participants, and the topic guide was refined as the focus groups and interviews progressed through debriefing with the two facilitators and through meetings with the wider research team. These discussions resulted in only minor changes regarding the order and wording of questions.

A thematic analysis approach was used to analyse data drawing on methods of constant comparison.26–29 SJW independently coded the seven transcripts using NVivo, and a secondary analysis team (SJW, AWAG, HMB, GL and TK) met to agree a preliminary coding frame, which was then agreed by the whole team. HMB independently coded two transcripts using the coding frame; discrepancies were minor and changes were made following discussion with the team. Codes were grouped into themes by SJW and HMB, where both within and between-participant variation was considered. Theme labelling and interpretation were continually discussed in regular team meetings. Data were assessed for saturation by SJW individually and across-group.30 Data saturation was determined when no new codes were emerging.

Results

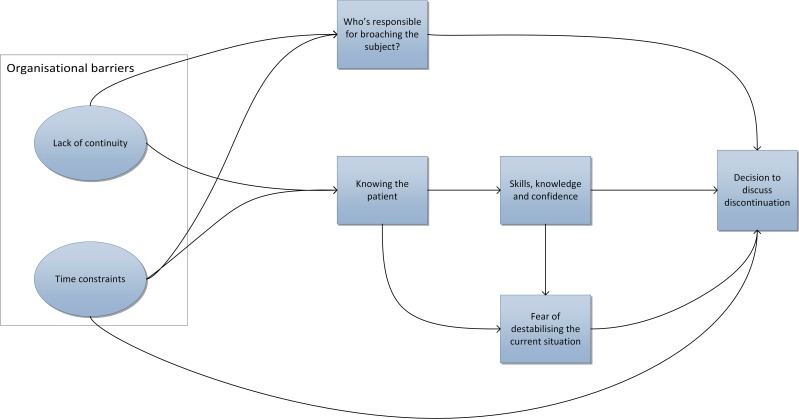

Five themes were identified from the data analysis regarding barriers and facilitators to discussing antidepressant discontinuation with patients (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram of the relationships between themes.

Theme 1: who is responsible for broaching the subject of discontinuation?

There were differing views about who is responsible for raising the topic of discontinuation in a consultation. A small number of HPs suggested it was the patient’s responsibility to broach the subject and that this expectation should be set when antidepressants are first prescribed.

I tend to say to people, ’Look, when you start it, I’d like you to continue for at least six months after you’ve felt well', and then right at the outset, I put the responsibility over to them and say, ’Look, one of the things about depression is that you lose control and the worst thing is to come to see the doctor and the doctor takes over control. So, as far as I’m concerned, you’re in control of these tablets and it’s your choice as to when you want to stop it but usually the recommendation is six months after you’ve been well'. I think most people—I haven’t audited it—at that stage, do come back round about six months-ish and are keen to stop and usually that works okay. (GP/09/0002)

One GP argued in favour of telling the patient at the initial prescription that they have the responsibility to initiate stopping and the choice to discontinue is up to them. By setting this expectation, it opens up the possibility of them taking control by broaching the subject with their GP when they are ready.

However, HPs highlighted there are problems with relying on the patient to broach the issue. Two nurses and a psychotherapist acknowledged that many patients may not instigate these conversations. One psychotherapist explained that patients may be reluctant to broach the subject due to expectations of how the doctor may respond, or perceiving the doctor to be more knowledgeable about the situation.

Even if they do get an appointment, I’ve met a lot of people who are really hesitant about asking about changes in medication, because of the response from the doctor perhaps or their perceived response… I think there’s often a worry, you know, the kind of, ’Doctor knows best, and they put me on this medication. So I don’t want to offend or I don’t want to question’. (PT/14/0002)

One GP suggested that when patients do not raise the idea of discontinuation, practitioners may assume that the patient wants to continue treatment. This mutual assumption that the HP wants the patient to continue, and that the patient him/herself wants to continue, may result in a form of collusion to maintain the status quo.

HPs appeared to be aware that relying on the patient to initiate discussion may be problematic, as evidenced through the way some HPs discussed the problem. It may therefore follow that the responsibility to initiate discussions about discontinuation should lie with the GP.

I think I’m guilty of this, it’s very easy just to keep kicking the can down the road and the patient keeps taking the medication because they feel they should and you keep prescribing it because you assume they still want it and there’s this kind of collusion that unless you actively intervene and say, ’Come and talk to me', or whatever. (GP/11/0001)

Some participants (including GPs) thought that it was the GP’s responsibility to broach the subject with patients; arguing that the person who prescribes the medication should be the person to initiate discussion of discontinuation. This was especially the case if a patient has been on the medication long term and may not have considered stopping. However, taking a proactive approach was not always considered feasible in practice; continuity may facilitate discussions of antidepressant withdrawal, although it is not always possible in primary care.

Some of the HPs referred to the discussion of discontinuation as a shared decision process. They talked about the need to assess the patient’s capacity in making decisions about withdrawal and negotiating with the patient to come to a shared decision about whether to discontinue. One GP also suggested it must be a shared decision as GPs are currently unable to manage the amount of work involved due to organisational factors which make having these conversations more challenging.

We’d say that because these patients are working and living in the community and are not sectioned and have capacity, that there is definitely a shared responsibility with the patient because it is their medicine and their mental health that we’re looking after. So I’m quite happy to say it’s a shared responsibility but it definitely can’t be just a primary care clinician’s because we’ll not manage to cope. (GP/19/0002)

The role of other HPs was also discussed with regard to conversations around discontinuing antidepressants. Although nurses have been considered to play a role in these discussions, there is acknowledgement that there are limitations regarding their authority and experience in managing medications, and often patients are signposted to their GP by their nurse. Social workers, pharmacists, care coordinators and psychiatrists were also mentioned as potential sources of additional support in stopping antidepressants, in some cases.

Theme 2: risk of destabilising current situation

Some HPs described it being easier to continue prescribing rather than raising discontinuation with patients and acknowledged a need to initiate more discussions about discontinuation with patients who may be eligible. There were concerns about instigating discussions with patients who are currently well as they did not want to risk destabilising the current situation. It was considered less risky to continue prescribing.

I think about—not just to patients but also to healthcare professionals or GPs—to reduce the medication is the concern that they might be working and reducing might destabilise a current stable situation, especially if the patient has been very, very difficult to control in the past and hasn’t got the support network perhaps. (GP/12/0001)

There was an assumption that patients also do not want to risk upsetting the current situation if they are feeling well.

I think for a lot that are on them, there is a massive fear factor about stopping, because they remember how awful they felt. They don’t want to feel like that. They feel well again and they just think, well, you know, I’d rather just keep the status quo. (GP/03/0004)

Theme 3: continuity and knowing the patient makes it easier to discuss discontinuation

Involvement in the initial prescription was perceived to place responsibility on the prescriber to prompt discontinuation later, and an opportunity to discuss and set patient expectations around withdrawal. Explaining to a patient at the initial prescription that discontinuation will be discussed at a later date was seen to be a facilitator in broaching the subject of discontinuation.

The very first consultation if you’re actually selling the idea of some medication being helpful, that it’s for a specific time period, expecting someone to be able to be able to come off it at about six months, so suggest your timescale of appointments and then say, ‘Oh, see you in about five months from the initiation of treatment. At that point, we can actually make a plan for withdrawal and I would be planning to withdraw it slowly if everything was going well in your life’. (GP/11/0004)

There were a number of facilitators to discussing discontinuation with patients. These included knowledge of the patient’s experience with antidepressants, their triggers for depression, why they started their medication and how things have changed since the initial prescription. This again suggests that continuity is beneficial, especially in terms of reducing risk.

Theme 4: a HP’s confidence in their skills and knowledge

Some of the HPs reported a lack of confidence, knowledge and skill with regards to antidepressant discontinuation which could act as a barrier to broaching the subject of stopping with patients. There was an awareness that discussing discontinuation with patients is something that could be improved on.

As a GP, I think for GPs, I think we’re very good at starting patients on it. We are good at titrating the dose up. Pretty good at picking the right medications suitable for the patients, because they have different side effects over spectrums. But what we’re probably not good enough, at the moment, is sort of the long-term managing and the coming-off part. (GP/12/0001)

HPs discussed a need for more support and information for themselves as well as for patients. They spoke about NICE guidance on antidepressant discontinuation, with many being unfamiliar with the guidance or not using them. They described being dissatisfied and, in one case, irritated by the current guidance. They highlighted that it is unclear (especially regarding tapering regimes), limited, not accessible and at times not applicable to real patients.

I don’t think there’s a lot of resources out there to kind of what to say and how to do it. I’m sure I’ve looked at the guidelines before and I thought a bit pants. (NP/12/0001)

Theme 5: organisational barriers and enablers to discussing discontinuation

The above processes are shaped by the context surrounding them, with environmental work contributing to decision-making around discontinuation. Some aspects of the healthcare system were described as further barriers to antidepressant discontinuation. A lack of continuity was reported with patients seeing different practitioners each time, and these practitioners were at times providing inconsistent recommendations. This may act as a barrier to discussing discontinuation due to the perceived need to be familiar with a patient to discuss withdrawal, and the idea that the responsibility for raising the topic of discontinuation lies with the HP who initially prescribed the antidepressant.

HPs repeatedly noted the challenge of time constraints in practice and how this is often a barrier to both initiating and managing discontinuation due to ten minute consultations not being long enough, and not having the time for review appointments.

Things are ticking along relatively okay, you know it’s not going to be necessarily a straightforward consultation and it might be time consuming, it might delay you and you haven’t got enough appointments anyway and da, da, da, da, you can see how that, as a clinician, restrains you from perhaps rocking the boat. (GP/11/0002)

HPs also mentioned the role of computer systems, explaining that patients can get lost in the system and that systems which adequately prompt medication reviews would be useful in broaching discontinuation with patients.

Discussion

In this paper we explored HP’s perspectives on discontinuing long-term antidepressants in primary care. Five themes were identified and covered who is responsible for broaching the subject of discontinuation, how fear of relapse can dissuade HPs from discontinuing, familiarity with the patient as enabling conversations around withdrawal, the lack of information and support for HPs, and organisational barriers and enablers. With regard to NPT,24 there is relational work that goes into negotiating responsibility and shared decision-making about antidepressant discontinuation. This relational work is founded on familiarity with the patient and knowledge of their experiences with depression and antidepressants. There is process work that goes into intervening, managing the consequences of withdrawal and avoiding destabilisation of a patient during and following discontinuation. This is founded on enacting generalisable clinical knowledge and practice with confidence. These processes are then shaped by contextual mechanisms and there is environmental work that goes into negotiating the decision to discontinue antidepressants.

An important theme identified in the current paper is contention in terms of who is responsible for broaching the topic of discontinuation. While the majority of HPs acknowledged that the responsibility may lie with the GP or be a shared decision with patients, they indicated that they currently do not initiate these conversations as much as they feel they ought to. There is limited evidence of this in previous research with one study reporting that some GPs expect patients to contact their practitioner when they wish to make changes to or discontinue their antidepressant.19

The shift in recent decades in primary care towards expert patients and self-care relies on an expectation of agency on behalf of the patient.31 However, depression and the long-term use of antidepressants are associated with reduced agency.32 HPs appear to be aware that there are barriers for patients in initiating conversations about withdrawal. The logical implication of this would be that GPs take the responsibility for initiating these conversations. However, despite GPs’ awareness of the need to improve on the current situation, these conversations about discontinuation are often not routinely being initiated.

GPs in the current study discussed a tension between being more proactive in their role and their full workload, which limits opportunities to demarcate time for focused discussion about discontinuation. Among the factors enabling discussion about discontinuation were knowing the patient and continuity of care. However, in current UK primary care, patients do not always see the same GP and GPs therefore may be unable to build the desired relationship with or acquire the desired knowledge of a patient before broaching the subject of stopping antidepressants. The way primary care often operates therefore does not lend itself to the desired context for discussing withdrawal, which results in a bias towards inaction. One implication is that familiarisation with the patient’s situation should be achieved through medical notes and discussion with the patient. However, time constraints may mean that consultations are not long enough to gather the desired information before discussing withdrawal. If it were agreed that initial discussions should be triggered by the GP, this would bring clarity to the currently uncertain system. With a more clearly articulated plan, GPs may be better able to arrange appointments (perhaps double appointments where necessary) to discuss discontinuation.

HPs reported fear of destabilising currently well patients by discontinuing antidepressants; a fear which has been evidenced in patients and GPs.19 20 33 This emphasis on avoiding negative outcomes over focusing on the longer term benefits of discontinuation may result in a preference for deferring discussions of withdrawal. However, when comparing antidepressant maintenance treatment to tapering with psychological support, long-term relapse rates for depression are comparable34–36 or in some cases lower for patients receiving psychological therapy.37 38 It may therefore be useful to reassure HPs that the risk of relapse may be minimised if discontinuation is accompanied by appropriate psychological support (although there is still a need for further work on providing support for patients who are discontinuing antidepressants).34 38 39

HPs report dissatisfaction with the current guidelines and acknowledge gaps in their own knowledge regarding antidepressant withdrawal. One other study has highlighted that GPs feel guidelines could provide more specific information about antidepressant treatment and discontinuation.19 This suggests a need to provide improved guidance and enhanced accessibility to and awareness of guidance on discontinuation, including specific guidance on reducing the doses of different antidepressants. This may increase HP confidence in their ability to support patients through discontinuation. This increased confidence in the HP ability to manage discontinuation may then also help to lessen the HP’s fears around destabilisation and relapse.

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first to explore HP’s perspectives of antidepressant discontinuation in UK primary care, with its larger sample consisting of a range of HP roles (including GPs, GP assistants, nurses, community mental health team workers and psychotherapists) which were lacking in previous research,20 21 33 40 41 and data reached saturation. GPs were the largest group among our interviewees, compared with the other professionals, which aligns with the current prescribing activity with the large majority of long-term antidepressants prescribed and monitored by GPs. This fits with our finding that GPs are often considered responsible for initiating conversations around withdrawal. However, we also identified that there are a number of professionals who may be involved in discontinuation (eg, pharmacists, social workers and care coordinators) and further research may be needed to explore these perspectives. For example, none of the practices in the current study managed discontinuation using practice pharmacists, who may play an important role in antidepressant withdrawal. In particular, it may be of interest to explore differences between professions.

The use of focus groups facilitated discussion and provided candid responses from participants. However, it is possible for discussions to become polarised or influenced by dominant members of the group. For example, in a focus group of nine GPs, there were two more dominant members and two members who spoke less frequently. As such, some participants’ views may be less well represented in a group setting. Giving participants an opportunity to provide feedback on the study’s findings might have helped provide greater representation.

Conclusion

Previous research has highlighted time constraints and fear of relapse as barriers to GPs discontinuing antidepressants and one previous study found that some GPs expected patients to initiate discussions of discontinuation. The current study has explored these barriers in detail in UK primary care health professionals and highlighted additional factors influencing decisions around discontinuation such as organisational barriers, a need for clearer guidance and a desire to know the patient well. Our findings highlight a need to support HPs in antidepressant discontinuation in terms of providing specific information and guidance on how to discontinue antidepressants. They also suggest HPs would benefit from support and guidance around fears of patient relapse and awareness of the need to initiate discussions about discontinuation. These findings have informed intervention development within the REDUCE programme. Future research is needed to explore ways in which HPs can be supported in managing antidepressant discontinuation in primary care and in a way that is acceptable and effective for patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to take this opportunity to thank all contributors, collaborators and team members of the REDUCE programme, including our Patient and Public Involvement representatives, Bryan Palmer, Susan Collins and Margaret Bell.

Footnotes

Contributors: HMB is a research fellow working on the REDUCE programme and contributed towards analysis and second coding of data, and the writing of this paper. SJW is the qualitative researcher currently working on the REDUCE programme and led the research, data collection, analysis and contributed to the writing of this paper. AWAG and GL are co-applicants on the REDUCE programme and contributed towards the analysis. WOB is the programme manager on the REDUCE programme, had oversight of the research and data collection. TK is the chief investigator of the research thereby leading on the programme and contributed towards analysis and interpretation of data. All coauthors (HMB, SJW, AWAG, GL, CRM, EM, WOB and TK) have substantially contributed to the writing of this article, provided critical revision and gave final approval of the published version. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This report is independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (Programme Grants for Applied Research, REDUCE RP-PG-1214-20004).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval to conduct the study was granted by the South Central Berkshire BResearch Ethics Committee and the Health Research Authority (Reference Number 16/SC/0472).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: This is a qualitative study and therefore the data are not suitable for sharing beyond what is contained within the report. Further information can be requested from the corresponding author.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Kendrick T, Stuart B, Newell C, et al. . Did NICE guidelines and the Quality Outcomes Framework change GP antidepressant prescribing in England? Observational study with time trend analyses 2003-2013. J Affect Disord 2015;186:171–7. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.06.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moore M, Yuen HM, Dunn N, et al. . Explaining the rise in antidepressant prescribing: a descriptive study using the general practice research database. BMJ 2009;339:b3999 10.1136/bmj.b3999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnson CF, Macdonald HJ, Atkinson P, et al. . Reviewing long-term antidepressants can reduce drug burden: a prospective observational cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2012;62:e773–e779. 10.3399/bjgp12X658304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Petty DR, House A, Knapp P, et al. . Prevalence, duration and indications for prescribing of antidepressants in primary care. Age Ageing 2006;35:523–6. 10.1093/ageing/afl023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Scholes S, Faulding S, Mindell J. Use of prescribed medicines, 2014:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ambresin G, Palmer V, Densley K, et al. . What factors influence long-term antidepressant use in primary care? Findings from the Australian diamond cohort study. J Affect Disord 2015;176:125–32. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cruickshank G, Macgillivray S, Bruce D, et al. . Cross-sectional survey of patients in receipt of long-term repeat prescriptions for antidepressant drugs in primary care. Ment Health Fam Med 2008;5:105–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Piek E, Kollen BJ, van der Meer K, et al. . Maintenance use of antidepressants in Dutch general practice: non-guideline concordant. PLoS One 2014;9:e97463 10.1371/journal.pone.0097463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Middleton DJ, Cameron IM, Reid IC. Continuity and monitoring of antidepressant therapy in a primary care setting. Qual Prim Care 2011;19:109–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sinclair JE, Aucott LS, Lawton K, et al. . The monitoring of longer term prescriptions of antidepressants: observational study in a primary care setting. Fam Pract 2014;31:419–26. 10.1093/fampra/cmu019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferguson JM. SSRI antidepressant medications: adverse effects and tolerability. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2001;3:22–7. 10.4088/pcc.v03n0105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Coupland C, Dhiman P, Morriss R, et al. . Antidepressant use and risk of adverse outcomes in older people: population based cohort study. BMJ 2011;343:d4551 10.1136/bmj.d4551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goodwin GM, Price J, De Bodinat C, et al. . Emotional blunting with antidepressant treatments: A survey among depressed patients. J Affect Disord 2017;221:31–5. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ilyas S, Moncrieff J. Trends in prescriptions and costs of drugs for mental disorders in England, 1998-2010. Br J Psychiatry 2012;200:393–8. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.104257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Health and Social Care Information Centre. Improving Access to Psychological Therapies Report, April 2015 Final and Quarter 4 2014/15. 2015. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB17880

- 16. Health and Social Care Information Centre. Prescriptions Dispensed in the Community - Statistics for England, 2006-2016 - NHS Digital. 2017. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/prescriptions-dispensed-in-the-community/prescriptions-dispensed-in-the-community-statistics-for-england-2006-2016-pas (accessed 2 Jul 2018).

- 17. Independent Research Service of the House of Commons Library. No Title. 2008. http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/%0AJohnson%0A

- 18. Eveleigh R, Grutters J, Muskens E, et al. . Cost-utility analysis of a treatment advice to discontinue inappropriate long-term antidepressant use in primary care. Fam Pract 2014;31:578–84. 10.1093/fampra/cmu043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bosman RC, Huijbregts KM, Verhaak PF, et al. . Long-term antidepressant use: a qualitative study on perspectives of patients and GPs in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:e708–e719. 10.3399/bjgp16X686641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Johnson CF, Williams B, MacGillivray SA, et al. . ‘Doing the right thing’: factors influencing GP prescribing of antidepressants and prescribed doses. BMC Fam Pract 2017;18:1–13. 10.1186/s12875-017-0643-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Davies J, Read J. A systematic review into the incidence, severity and duration of antidepressant withdrawal effects: Are guidelines evidence-based? Addict Behav 2018;S0306-4603:30834–7. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maund E, Dewar-Haggart R, Williams S, et al. . Barriers and facilitators to discontinuing antidepressant use: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. J Affect Disord 2019;245 10.1016/j.jad.2018.10.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. REDUCE (REviewing long term anti-Depressant Use by Careful monitoring in Everyday practice). 2016. https://www.southampton.ac.uk/medicine/academic_units/projects/reduce.page (accessed 29 Jun 2018).

- 24. May C, Finch T. Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: an outline of normalization process theory. Sociology 2009;43:535–54. 10.1177/0038038509103208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Asbury J-E. Overview of focus group research. Qual Health Res 1995;5:414–20. 10.1177/104973239500500402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Glaser BG. Theoretical sensitivity. Mill Valley CA: Sociology Press, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Glaser BG. Discovery of grounded theory. Chicago: Aldine, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Onwuegbuzie AJ, Dickinson WB, Leech NL, et al. . A Qualitative Framework for Collecting and Analyzing Data in Focus Group Research. Int J Qual Methods 2009;8:1–21 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/160940690900800301 10.1177/160940690900800301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Department of Health. The Expert Patient: A New Approach to Chronic Disease Management for the 21st Century. 2001. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20120511062115/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4018578.pdf (accessed 29 Jun 2018).

- 32. Cartwright C, Gibson K, Read J. Personal agency in women’s recovery from depression: the impact of antidepressants and women’s personal efforts. Clin Psychol 2018;22:72–82. 10.1111/cp.12093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dickinson R, Knapp P, House AO, et al. . Long-term prescribing of antidepressants in the older population: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2010;60:e144–e155. 10.3399/bjgp10X483913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kuyken W, Hayes R, Barrett B, et al. . Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment in the prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (PREVENT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;386:63–73. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62222-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kuyken W, Byford S, Taylor RS, Watkins E, et al. . Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy to prevent relapse in recurrent depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008;76:966–78. 10.1037/a0013786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bockting CLH, ten Doesschate MC, Spijker J, et al. . Continuation and maintenance use of antidepressants in recurrent depression. Psychother Psychosom 2008;77:17–26. 10.1159/000110056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fava GA, Grandi S, Zielezny M, et al. . Cognitive behavioral treatment of residual symptoms in primary major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:1295–9. 10.1176/ajp.151.9.1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fava GA, Rafanelli C, Grandi S, et al. . Prevention of recurrent depression with cognitive behavioral therapy: preliminary findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:816–20. 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Huijbers MJ, Spijker J, Donders AR, et al. . Preventing relapse in recurrent depression using mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, antidepressant medication or the combination: trial design and protocol of the MOMENT study. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:125 10.1186/1471-244X-12-125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Iden KR, Hjørleifsson S, Ruths S. Treatment decisions on antidepressants in nursing homes: a qualitative study. Scand J Prim Health Care 2011;29:252–6. 10.3109/02813432.2011.628240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pollock K, Grime J. Primary care practice consultations for depression : qualitative study. Prim Care 2002;325:687–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-027837supp001.pdf (218.4KB, pdf)