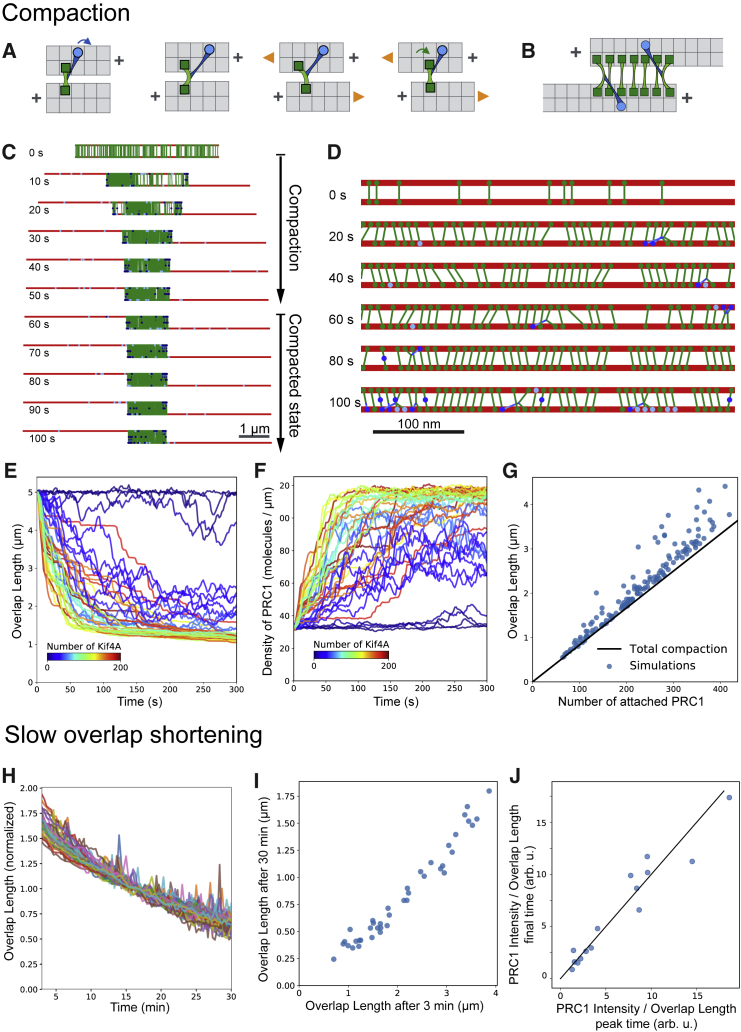

Figure 6.

Model of Overlap Formation

(A) Sliding mechanism. KIF4A pulls a PRC1 molecule that is linking two microtubules, inducing strain on both PRC1 heads. The top PRC1 head releases the strain by biased diffusion toward the plus end. The bottom PRC1 head releases the strain by biased diffusion or microtubule sliding.

(B) PRC1 compaction stalls microtubule sliding.

(C) Representative simulation with 2 microtubules (length 5 μm), 200 PRC1 and 132 KIF4A (Table S1, set 1). See Video S5.

(D) Magnified view of the simulation shown in (C). See Video S6.

(E) Dynamics of overlap length in simulations (mircotubule length 5 μm; 200 PRC1; Table S1, set 1). Lines stand for individual simulations where the number of KIF4A varies from 0 to 200 (see color scale).

(F) PRC1 density for the same simulations as in (E).

(G) Scatterplot showing the correlation between the length of the overlap and the number of PRC1 molecules attached in the overlap after 300 s. Each dot represents one simulation (Table S1, set 1) but with randomized numbers of KIF4A (30–200) and PRC1 (100–600) and microtubule length (3–7 μm). The diagonal black line represents full compaction (i.e., one molecule per 8 nm).

(H) Shortening of overlaps in different simulations containing 100 KIF4A and between 100 and 600 PRC1 (Table S1, set 1). In these simulations, compaction is reached earlier than 3 min after KIF4A addition (E), and this plot focuses on later times.

(I) Overlap at 3 min (when total compaction reached) versus overlap at 30 min for data shown in (H).

(J) Comparison between the experimental ratio between PRC1 intensity and overlap length, at the time of maximal overlap (x axis) and at final time (y axis). Dots represent individual overlaps from the data shown in Figure 3B. The diagonal indicates perfect conservation of this quantity.

See also Figure S5.