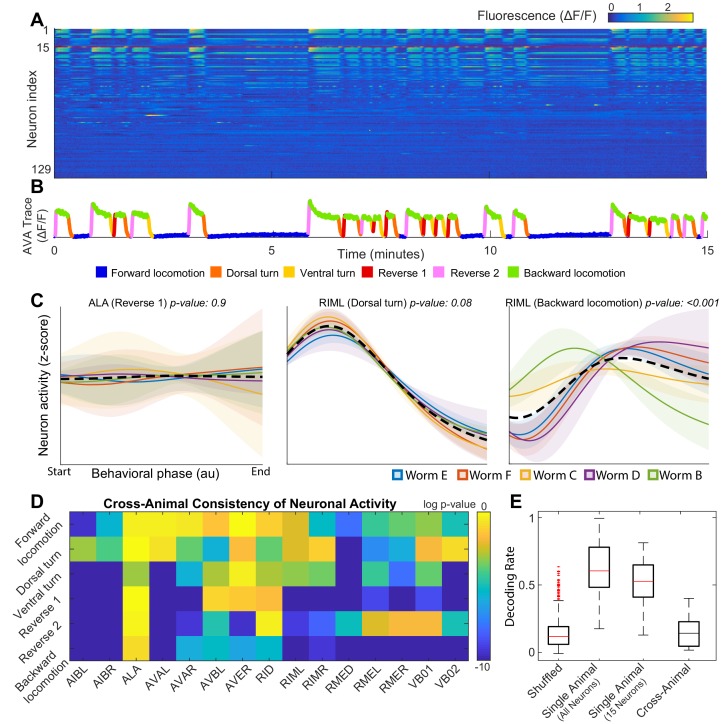

Figure 1. Neuronal activity is consistently different in different individuals.

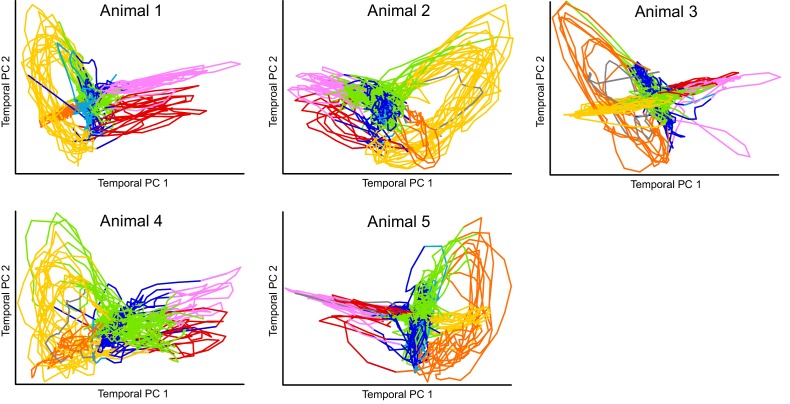

(A) Calcium signals () recorded in one animal for ∼15 min by Kato et al. (2015). Each row represents a single neuron. The top 15 rows (above the red line) correspond to neurons unambiguously identified in all animals (shared neurons). (B) Trace of the AVA neuron colored by behavioral state as defined by Kato et al. (2015). (C) Neuronal activity of representative neurons plotted as a function of behavioral phase (Materials and methods) in a single behavior grouped by animal. Colored solid lines show mean activity for each animal. Shaded regions show 95% confidence intervals. Mean and confidence intervals are computed across multiple cycles of the same behavior in each animal. The dashed black line shows the mean across all cycles of the behavior in all animals. The cross-animal mean for ALA and RIML (Dorsal turn) is a good approximation of activity in each animal individually. In contrast, the cross-animal mean of RIML (Backward locomotion) does not represent any individual. Thus, activity of RIML is consistently different among individuals during backward locomotion. (D) Probabilities that neuronal activity from different individuals was drawn from the same distribution (Materials and methods) computed for each neuron in each locomotor behavior. Activity of most neurons differs consistently among individuals in at least one locomotor behavior. (E) Attempts to decode the onset of backwards locomotion are successful within each animal individually using either all neurons or the 15 shared neurons. This confirms that neuronal activation is stereotyped in each animal. Yet decoding fails across animals. Probability of decoding onset of backwards locomotion in one animal on the basis of neuronal activity averaged across other four animals is indistinguishable from chance. Thus, averaging neuronal activity across individuals disrupts behaviorally relevant information. Box plots show distribution of decoding rates bootstrapped across animals and bi-partitions of the data into training and validation datasets (Materials and methods).