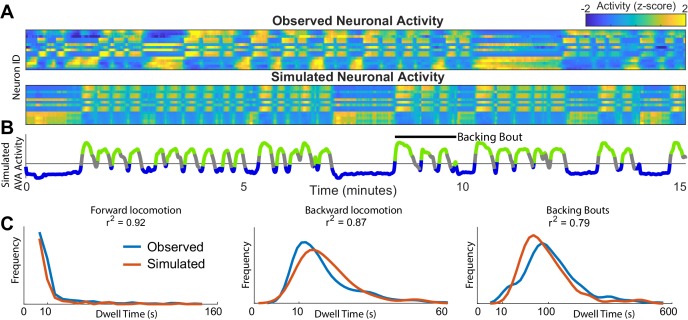

Figure 2. Simulations of the dynamics faithfully reproduce neuronal activity and behavioral statistics.

(A) Experimentally observed (top) and simulated (bottom) activity of 15 shared neurons plotted as in Figure 1A. (B) Trace of the simulated AVA neuron colored according to the inferred behavioral state. In contrast to Figure 1, color here expresses neuronal activity as z-score computed for each neuron individually. Behavioral states are assigned based on experimentally observed distribution of behaviors for each point in phase space (blue forward locomotion; green backward locomotion) (Materials and methods). Both A and B are plotted on the same time-axes. Because of under-sampling, transitions between forward and backward locomotions are left unassigned (gray). (C) Dwell time distributions for forward locomotion, backward locomotion and backing bouts (blue experimentally observed; orange simulated). Backing bouts were defined as repeated episodes of backing behavior separated by short forward locomotion states lasting at most 30 frames ( 10 s) (e.g. black line in B). Although the manifold is constructed on the basis of transition probabilities between states separated by <1 s., the manifold successfully predicts statistics of behaviors over 100 s.