Abstract

Aims

To provide a model‐based prediction of individual urinary glucose excretion (UGE) effect of ipragliflozin, we constructed a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) model and a population PK model using pooled data of clinical studies.

Methods

A PK/PD model for the change from baseline in UGE for 24 hours (ΔUGE24h) with area under the concentration–time curve from time of dosing to 24 h after administration (AUC24h) of ipragliflozin was described by a maximum effect model. A population PK model was also constructed using rich PK sampling data obtained from 2 clinical pharmacology studies and sparse data from 4 late‐phase studies by the NONMEM $PRIOR subroutine. Finally, we simulated how the PK/PD of ipragliflozin changes in response to dose regime as well as patients' renal function using the developed model.

Results

The estimated individual maximum effect were dependent on fasting plasma glucose and renal function, except in patients who had significant UGE before treatment. The PK of ipragliflozin in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients was accurately described by a 2‐compartment model with first order absorption. The population mean oral clearance was 9.47 L/h and was increased in patients with higher glomerular filtration rates and body surface area. Simulation suggested that medians (95% prediction intervals) of AUC24h and ΔUGE24h were 5417 (3229–8775) ng·h/mL and 85 (51–145) g, respectively. The simulation also suggested a 1.17‐fold increase in AUC24h of ipragliflozin and a 0.76‐fold in ΔUGE24h in T2DM patients with moderate renal impairment compared to those with normal renal function.

Conclusions

The developed models described the clinical data well, and the simulation suggested mechanism‐based weaker antidiabetic effect in T2DM patients with renal impairment.

Keywords: ipragliflozin, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, Suglat, type 2 diabetes mellitus

What is already known about this subject

Primary results of all clinical trials used in the article have been reported.

Pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) results of ipragliflozin in phase I and clinical pharmacology studies have been reported in the individual clinical study reports.

A mechanistic PK/PD model based on the European clinical data of ipragliflozin in healthy subjects and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients has been reported (AAPS J 12(S2): R6400, 2010).

What this study adds

We have developed an integrated PK/PD model of ipragliflozin in Japanese healthy subjects and patients with T2DM to predict UGE by the exposure of ipragliflozin.

We have constructed a population PK model for ipragliflozin in Japanese patients with T2DM to estimate ipragliflozin exposure.

The developed PK/PD and population PK models enable individual predictions of UGE, which will help develop a subsequent exposure–response model for the long‐term antidiabetic effects of ipragliflozin.

1. INTRODUCTION

Sodium‐dependent glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are a novel class of drug that inhibit the reabsorption of glucose from the kidneys and stimulate urinary glucose excretion, thereby lowering blood glucose levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1 Ipragliflozin (Suglat) is a SGLT2‐selective inhibitor2 codeveloped by Astellas Pharma Inc. and Kotobuki Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. for the treatment of T2DM, and has been approved in Japan and Korea. In Japan, use as monotherapy or in combination with antihyperglycaemic agents (metformin, pioglitazone, sulfonylureas, α‐glucosidase inhibitors, dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors, meglitinides, glucagon‐like peptide‐1 agonists or insulin) at a 50‐mg dose once daily before or after breakfast have been approved. The dosage can be increased to 100 mg once daily if the efficacy of the 50 mg dose is insufficient. In Korea, use as monotherapy or in combination with metformin, pioglitazone or add on treatment with combination of metformin and sitagliptin have been approved, and the recommended oral dosage is 50 mg once daily before or after breakfast.

In phase I and clinical pharmacology studies in Japanese healthy subjects and patients with T2DM, ipragliflozin was consistently well tolerated, and exposure and urinary glucose excretion (UGE) were found to increase dose‐dependently.3, 4, 5 In a 12‐week phase II study, dose‐dependent decreases in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels were observed when ipragliflozin was given by once daily administration at 12.5, 25, 50 and 100 mg.6 In a phase III study in Japanese patients with T2DM (BRIGHTEN Study), ipragliflozin was well tolerated on once daily administration at 50 mg for 16 weeks.7 Ipragliflozin was superior to a placebo in decreasing FPG and HbA1c levels, with lowering body weight and blood pressure.7 The long‐term safety and efficacy of ipragliflozin have been established in phase III studies in T2DM patients.8, 9 By contrast, in T2DM patients with moderate renal impairment, a weaker antidiabetic effect was reported.9

The pharmacokinetics (PK) of ipragliflozin is characterized by high oral bioavailability (>90%),10 high protein binding ex vivo (~96%),11 a major metabolic pathway of glucuronidation by multiple UDP‐glucuronosyltransferases12, 13 and a very low urinary excretion ratio of unchanged ipragliflozin (approximately 1%).3, 4, 5

The aim of this study was to provide a model‐based prediction method for the PK/pharmacodynamics (PD) of ipragliflozin and to determine factors that influence the pharmacological effect on UGE in Japanese patients with T2DM.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

The exposure of ipragliflozin and urine glucose excretion data from the phase I study in healthy subjects (Study A) and the clinical pharmacology studies in T2DM patients (Studies B and C) were used to establish the PK/PD model of ipragliflozin. The PK data from 6 clinical studies (Studies B–G) in T2DM patients were used to develop a population PK (PopPK) model of ipragliflozin. All studies were conducted in accordance with ethical principles based on the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice, and International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and were approved by an institutional review board. All subjects provided written informed consent. The brief summaries of the clinical studies are as follows;

Study A (CL‐0101, NCT01121198, phase I) 3 was a single‐centre, placebo‐controlled, single‐blind, randomized, sequential‐group, dose‐escalation study which consisted of 2 parts: single oral dosing in the fasting state and multiple oral administration following food intake (breakfast). In the single‐dosing arm, ipragliflozin at a dose of 1, 3, 10, 30, 100 or 300 mg or matching placebo was administered to healthy subjects in the fasting state (n = 48). Blood samples for measurement of plasma ipragliflozin concentration were collected at predose, and at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24, 36, 48 and 72 hours after administration. Urine samples were collected for 24 hours before drug administration and 0–2, 2–4, 4–6, 6–8, 8–10, 10–12, 12–24, 24–36, 36–48 and 48–72 hours after administration, and UGE for 24 hours (UGE24h) was calculated at and after administration. In the multiple‐dosing arm, ipragliflozin at 20, 50 or 100 mg or placebo was administrated on Day 1, and after Day 3, subjects received single daily oral doses of ipragliflozin or placebo for 7 days after a standardized meal (n = 36). Blood samples for measurement of plasma ipragliflozin concentration were collected at predose and at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24, 36 and 48 hours after administration on Days 1 and 9. Urinary samples were collected for 24 hours before drug administration and 0–2, 2–4, 4–6, 6–8, 8–10, 10–12, 12–24, 24–36, and 36–48 hours after administration on Days 1 and 9, and 48–72 and 72–96 hours after administration on Day 9. From day 3 to day 8, urine collections were conducted every 24 hours. UGE24h was calculated at predose and at every dosing interval.

Study B (CL‐0070, NCT01023945, Phase I) 4 was a 2‐week, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel group, multiple‐dose study that assessed the daily profile of PK and PD in T2DM patients. Subjects were randomized into 3 treatment groups (placebo or ipragliflozin 50 or 100 mg, once daily of oral dose). Blood samples for measurement of plasma ipragliflozin concentration were collected predose and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 10, 12 and 24 hours after administration on Day 14. Urine samples were collected for 24 hours before drug administration and 0–4, 4–10, and 10–24 hours after administration on Day 14, and UGE24h was calculated predose and after administration on Day 14.

Study C (CL‐0073, NCT01097681, Clinical pharmacology study) 5 was an open‐label, single‐dose study which assessed the effect of renal function on PK, PD and safety. Ipragliflozin was administered as a single oral dose of 50 mg to T2DM patients with normal renal function (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2), mild renal impairment (eGFR 60–90 mL/min/1.73 m2), and moderate renal impairment (eGFR 30–60 mL/min/1.73 m2). Blood samples for measurement of plasma ipragliflozin concentration were collected at predose and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 36, 48 and 72 hours after administration on Day 1. Urine samples were collected for 24 hours before drug administration and 0–4, 4–10, 10–24, 24–36, 36–48, and 48–72 hours after administration on Day 1, and UGE24h was calculated at predose and after administration on Day 1.

Study D (CL‐0103, NCT00621868, Phase II) 6 was a 12‐week, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multiple dose study which assessed the dose–response of ipragliflozin. Subjects were randomized into 1 of 5 treatment groups (placebo or ipragliflozin 12.5, 25, 50 and 100 mg at once daily of oral dose). Blood samples for measurement of predose plasma ipragliflozin concentration were collected at 0, 2, 4, 8 and 12 weeks.

Study E (CL‐0105, NCT01057628, Phase III) 7 was a 16‐week, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled monotherapy study to assess the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ipragliflozin. Subjects were randomized into 1 of 2 treatment groups (placebo or ipragliflozin 50 mg at once daily of oral dose). Blood samples for measurement of predose plasma ipragliflozin concentration were collected at 4, 8, 12 and 16 weeks.

Study F (CL‐0121, NCT01054092, Long‐term study) 8 was a 52‐week, open‐label, uncontrolled monotherapy study to assess long‐term safety, tolerability and efficacy of ipragliflozin. Ipragliflozin was given by once daily oral administration at 50 mg, which was increased to 100 mg in subjects who met the dose‐escalation criteria at 20 weeks after the start of ipragliflozin treatment. Blood samples for measurement of predose plasma ipragliflozin concentration were collected every 4 weeks from 4 to 52‐week assessment visits.

Study G (CL‐0072, NCT01316094, Long‐term study with renal impairment patients) 9 was a 52‐week study to assess the long‐term safety and efficacy of ipragliflozin. T2DM patients with mild or moderate renal impairment who were currently on diet/exercise therapy alone or in combination with an α‐glucosidase inhibitor, a sulfonylurea, or pioglitazone in a constant dosing were randomized in the study. Ipragliflozin was given by once daily oral administration at 50 mg or placebo for 24 weeks under double‐blind conditions. At 24 weeks, subjects who are willing to continue participation in the study receive study drug for another 28 weeks in an open label condition. Dose escalation to 100 mg is acceptable if subjects met the dose‐escalation criteria at 20 weeks. The data for 24 weeks (before dose escalation) were included in this analysis. Blood samples for measurement of predose plasma ipragliflozin concentration were collected at 8, 16, 24, 32, 40 and 52 weeks.

2.2. Assay for plasma levels of ipragliflozin

The concentrations of unchanged ipragliflozin in plasma were measured by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. The lower limit of quantification was 1 ng/mL when 0.2 mL plasma was used.14

2.3. Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were calculated, including mean, standard deviation and range for continuous variables. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical data. Simulation results were summarized by median and the prediction interval. All statistical data processing and summarization were performed using SAS version 9.1 and R version 2.13.1 (or subsequent versions). Area under the concentration–time curve (AUC) of ipragliflozin was calculated by noncompartment analysis by Phoenix WinNonlin ver. 6.2. All NONMEM analysis was performed by the first‐order conditional estimation method with interaction using NONMEM version 7.1.0.

2.4. PK/PD model

AUC of ipragliflozin from time of dosing to 24 h after administration (AUC24h) was used as an independent exposure variable to establish the PK/PD relationship of ipragliflozin. Individual AUC24h of ipragliflozin in Studies A, B and C were calculated by noncompartment analysis. UGE24h at predose and after dose were calculated for the same time interval of AUCs. The relationship between AUC24h of ipragliflozin and change in UGE24h from baseline (ΔUGE24h) was described by a maximum effect (Emax) model by NONMEM. The model was parameterized by Emax and exposure (AUC24h) producing 50% of Emax (EC50) as follow:

| (1) |

Interindividual variability (η) in Emax or EC50 was not modelled because only 1 or 2 ΔUGE24h data per subject were available. For the residual error, a combination of additive (εabs) and proportional errors (εprop) was selected based on the objective function values (OFV).

The potential of the following factors at baseline to influence Emax and EC50 were then explored: disease state (healthy/T2DM), dosage effect (single/multiple), food effect (fasted/fed), history of 1 or more oral antidiabetics treatment, disease duration, sex, age, body weight, body mass index, body surface area (BSA), renal function classification, urea nitrogen, urinary creatinine, urinary albumin corrected by creatinine, and urinary protein. Addition of covariate candidates was assessed based on exploratory plots and a decrease in OFV in a step‐wise manner, with a statistical significance of P < .05 and backward deletion applied at P < .001.

2.5. Population PK model

To obtain individual AUC of ipragliflozin from plasma trough concentration, a PopPK model was constructed using nonlinear mixed effect modelling by NONMEM. The base model for the PK of ipragliflozin was developed using the sequential concentration–time data from 2 clinical pharmacology studies in T2DM patients (studies B and C). A 2‐compartment model with first order absorption, implemented in ADVAN4, the built‐in subroutines in NONMEM, was used as the base model. The model was parameterized by first order absorption rate constant (Ka), oral clearance (CL/F), apparent intercompartment clearance (Q/F), and apparent volumes of distribution in the central (Vc/F) and peripheral (Vp/F) compartments (TRANS4). Interindividual variability (η) for all the PK parameters and the residual random error (ε) were assumed to be log‐normal and proportional, respectively.

This base model was then utilized as a prior for the analyses of trough concentration data from the 4 late‐phase studies (studies D–G) using NONMEM $PRIOR subroutine. The degree of freedom (ν) of omega (Ω) prior (the degree of informativeness about Ω) was set to N – λ, where N is the number of patients utilized to establish the prior model and λ is the number of parameters.15 Covariates were explored for CL/F regarding the following variables: age, sex, body weight, body mass index, BSA at baseline, aspartate amino transferase, alanine amino transferase, alkaline phosphatase, serum albumin, total protein (TPRO), total bilirubin (TBIL), GFR, and food effect at each assessment visit and treatment visit. Addition of covariate candidates was assessed by a stepwise manner, with statistical significance of P < .05 and backward deletion applied at P < .001.

2.6. Model evaluation

Models were evaluated by assessing goodness‐of‐fit (GOF) plots. Predictive performance of the final PopPK model was evaluated by visual prediction check (VPC) with using individual demographic data from 887 T2DM patients in the analysis dataset. Robustness of the final PK/PD and PopPK models was assessed by nonparametric bootstrap.

2.7. Simulation

The steady‐state PK/PD profiles of ipragliflozin at once daily administration of 12.5, 25, 50 and 100 mg were simulated for 887 Japanese patients with T2DM enrolled in the 6 clinical studies (Studies B–G). AUC24h was calculated using individual post‐hoc CL/F from the final PopPK model and UGE24h was simulated by the final PK/PD model. The effect of renal function on the exposure of plasma ipragliflozin was also investigated.

2.8. Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY,27 and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18.28

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographics and laboratory variables

A summary of demographic and clinical laboratory variables for subjects administrated placebo or ipragliflozin is presented in Table 1. Estimated GFR (mL/min/1.73m2) was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation modified for Japanese patients with chronic kidney disease,16 and GFR (mL/min) corrected by individual BSA was used for modelling. BSA was calculated by the Du Bois equation.17

Table 1.

Summary of demographics and laboratory variables for healthy and T2DM patients

| Study | Study A | Study B and C | Study D, E, F, and G† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I | Clinical pharmacology | Phase II, III | ||

| Subjects | Healthy volunteers | T2DM patients | T2DM | Total in T2DM |

| Number (active/placebo) | n = 84 (60/24) | n = 53 (43/10) | n = 834 (652/182) | n = 887 (695/192) |

| PK/PD variables | AUC24h, UGE24h, FPG | AUC24h, UGE24h, FPG | Ctrough, FPG, HbA1c | |

| Sex n (%) | ||||

| Male | 84 (100.0%) | 37 (69.8%) | 569 (68.2%) | 606 (68.3%) |

| Female | 0 (0.0%) | 16 (30.2%) | 265 (31.8%) | 281 (31.7%) |

| Age category n (%) | ||||

| <65 y | 84 (100.0%) | 34 (64.2%) | 563 (67.5%) | 597 (67.3%) |

| ≥65 y | 0 (0.0%) | 19 (35.8%) | 271 (32.5%) | 290 (32.7%) |

| Renal function n (%)† | ||||

| Normal (eGFR≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 58 (69.0%) | 22 (41.5%) | 296 (35.5%) | 318 (35.9%) |

| Mild (eGFR 60 to <90 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 26 (31.0%) | 21 (39.6%) | 445 (53.4%) | 466 (52.5%) |

| Moderate (eGFR 30 to <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (18.9%) | 93 (11.2%) | 103 (11.6%) |

| Severe (eGFR<30 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Age (y) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 25.4 (5.2) | 59.3 (10.4) | 58.7 (10.1) | 58.7 (10.1) |

| Range | (20–41) | (34–75) | (26–86) | (26–86) |

| Body weight (kg) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 64.08 (5.26) | 69.06 (11.89) | 68.14 (12.13) | 68.19 (12.11) |

| Range | (51.4–80.1) | (45.6–100.8) | (41.5–128.0) | (41.5–128.0) |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 21.59 (1.55) | 25.78 (3.14) | 25.60 (3.62) | 25.62 (3.59) |

| Range | (18.5–25.8) | (20.0–33.9) | (19.1–40.6) | (19.1–40.6) |

| BSA (m 2 ) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.758 (0.086) | 1.744 (0.183) | 1.731 (0.178) | 1.732 (0.178) |

| Range | (1.56–2.03) | (1.35–2.14) | (1.28–2.47) | (1.28–2.47) |

| GFR (mL/min) †, ‡ | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 101.28 (15.68) | 84.28 (29.29) | 84.50 (23.49) | 84.46 (23.91) |

| Range | (72.2–153.0) | (29.8–169.8) | (24.1–175.4) | (24.1–181.5) |

| Total protein (g/dL) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.73 (0.31) | 7.19 (0.47) | 7.28 (0.40) | 7.27 (0.40) |

| Range | (5.8–7.5) | (6.1–8.3) | (5.8–9.1) | (5.8–9.1) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.76 (0.23) | 0.81 (0.33) | 0.81 (0.31) | 0.81 (0.31) |

| Range | (0.4–1.3) | (0.4–2.7) | (0.2–3.6) | (0.2–3.6) |

| FPG (mg/dL) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 92.6 (5.1) | 156.0 (40.2) | 169.1 (37.7) | 168.3 (37.9) |

| Range | (83–110) | (84–255) | (73–342) | (73–342) |

| HbA1c (NGSP) (%) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.11 (0.19) | 8.05 (1.45) | 8.08 (0.82) | 8.08 (0.87) |

| Range | (4.8–5.6) | (5.8–14.0) | (6.3–11.4) | (5.8–14.0) |

In study G, eGFR during placebo run‐in period were summarized as the baseline values

eGFR corrected by individual BSA were summarized

AUC24h, area under the concentration–time curve from time of dosing to 24 h after administration; BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; Ctrough, plasma trough concentration; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin; PK/PD, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic; SD, standard deviation; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; UGE24h, change in urinary glucose excretion for 24 hours

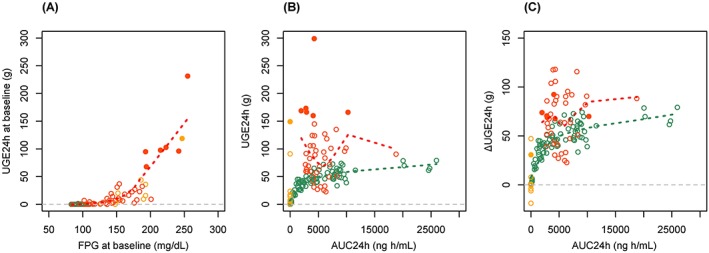

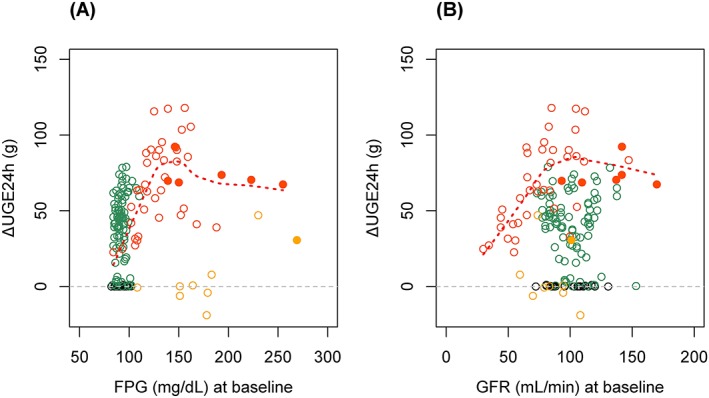

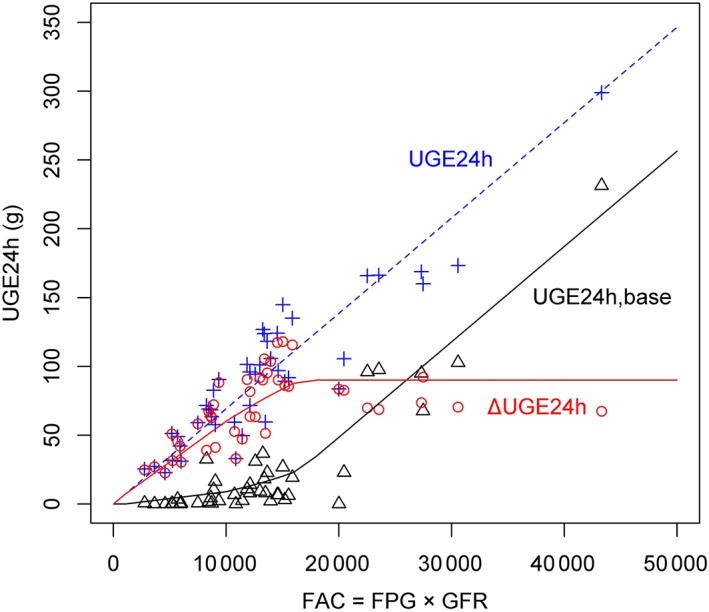

3.2. Exploratory assessment of PD

A total of 686 UGE24h data from 137 subjects (84 healthy subjects and 53 T2DM patients) were collected at predose, after the first dose, during multiple doses and after the last dose. A dose‐dependent increase in UGE was observed after single and multiple doses both in healthy subjects and T2DM patients. UGE24h was generally higher in patients with T2DM than in healthy subjects and dependent on renal function.3, 4, 5 Scatter plots of (A) UGE24h at baseline (UGE24h, base) vs FPG at baseline, (B) absolute UGE24h after dose vs AUC24h, (C) ΔUGE24h vs AUC24h and are presented in Figure 1. In the exploratory plots, a total of 177 measurements after first and last doses that have corresponding exposure values (AUC24h) were plotted. T2DM patients with high FPG levels (>~180 mg/dL) had significant UGE before ipragliflozin treatment. UGE is known to be determined by plasma glucose levels and renal function,18, 19 which could explain the correlations among ΔUGE24h, FPG and GFR observed in the studies (Figure 2). ΔUGE24h in T2DM patients was generally dependent on both FPG and GFR except for some patients with very high baseline UGE24h (UGE24h, base) who appeared not to follow the trend. As ΔUGE24h depends on both FPG and GFR, a hybrid parameter, FAC, which is a product of FPG and GFR, was calculated and used as a predictor of UGE24h,base, UGE24h, and ΔUGE (Figure 3). The plots clearly suggested that ΔUGE24h of patients with zero or minimal UGE24h, base depends strongly on FAC, whereas ΔUGE24h of patients with significant UGE24h, base was roughly constant regardless of FAC. The apparent threshold of FAC for UGE24h, base was about 16 000 to 18 000, which is consistent with the threshold at which glucose appears in urine being at a plasma glucose level of 160–180 mg/dL18, 19 when subjects have normal GFR of around 100 mL/min. Based on the exploratory plots, 18 000 was used as the threshold for FAC in further modelling.

Figure 1.

Scatter plots of A, baseline change in urinary glucose excretion for 24 hours (ΔUGE24h) vs fasting plasma glucose (FPG), B, absolute UGE24h vs area under the concentration–time curve from time of dosing to 24 h after administration (AUC24h) and C, ΔUGE24h vs area under the concentration–time curve from time of dosing to 24 h after administration AUC24h. Green circles: healthy subjects (ipragliflozin), black circles: healthy subjects (placebo), red circles: type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients (ipragliflozin), yellow circles: T2DM patients (placebo), filled circles: patients with significantly high baseline UGE24h (>50 g), green dotted line: locally weighted scatterplot smoothing line in healthy subjects (ipragliflozin), red dotted line: locally weighted scatterplot smoothing line in T2DM patients (ipragliflozin).

Figure 2.

Relationship between change in urinary glucose excretion for 24 hours (ΔUGE24h) and A, fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and B, glomerular filtration rate (GFR) at baseline. Green circles: healthy subjects (ipragliflozin), black circles: healthy subjects (placebo), red circles: type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients (ipragliflozin), yellow circles: T2DM patients (placebo), filled circles: patients with significantly high baseline UGE24h (>50 g), red dotted line: locally weighted scatterplot smoothing line in T2DM patients (ipragliflozin)

Figure 3.

Relationship between urinary glucose excretion for 24 hours (UGE24h) and a hybrid parameter FAC (= fasting plasma glucose [FPG] × glomerular filtration rate [GFR]) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus administered ipragliflozin. Observed UGE24h data and schematic lines are plotted. Blue plus and dashed line: UGE24h after dose (UGE24h). Black triangle and dashed line: UGE24h at baseline (UGE24h, base). Red circles and bold line: change in UGE24h from baseline (ΔUGE24h)

3.3. PK/PD model

A total of 155 ΔUGE24h data points from 111 subjects (65 healthy subjects and 46 T2DM patients) were included in the analysis. UGE24h values that have no corresponding AUC24h as the same collection interval were excluded from the analysis. Additionally, data for low doses (1 and 3 mg) were also excluded from analysis because no significant effects on UGE were observed throughout the evaluation period.

A PK/PD model for ΔUGE24h with AUC24h of ipragliflozin was described by an Emax model. The parameter estimates in the final model are shown in Table 2. Based on the exploratory assessment, FPG and GFR were preset as covariates of Emax as products of power functions (Equation 2). The covariate exploration for Emax and EC50 elucidated that only a threshold for FAC was significant as an additional covariate for Emax (Equation 3). Other laboratory variables and background demographic factors had no significant impact on Emax or EC50.

| (2) |

| (3) |

Emax was 72.3 g/24 h for subjects with the reference FPG of 100 mg/dL and the reference GFR of 90 mL/min. The fixed effect model indicates Emax depends on FPG and GFR up to a threshold value (18‚000) of FAC (Equation 2), and then Emax becomes constant at 107 g/24 h (Equation 3). EC50 for glucose excretion effect was 1590 ng·h/mL. The residual error of ΔUGE24h was ±352 mg and 19.8% (when Emax = 72 g/24 h, it is approximately ±14 g) for additive and proportional errors, respectively. The residual error of the final model was comparable to the interindividual variability (IIV) of ΔUGE24h assessed in placebo patients (±20 g).

Table 2.

Parameter estimates in the final pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | RSE (%)† | Lower 95%CI‡ | Upper 95%CI‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population mean | |||||

| EC50 (ng·h/mL) | 1590 | 220 | 13.8% | 1160 | 2020 |

| Emax (g/24 h): FAC ≤ 18 000 | 72.3 | 3.05 | 4.22% | 66.3 | 78.3 |

| Emax (g/24 h): FAC > 18 000 | 107 | 7.23 | 6.76% | 92.8 | 121 |

| FPG effect on Emax | 1.37 | 0.120 | 8.76% | 1.13 | 1.61 |

| GFR effect on Emax | 0.623 | 0.0863 | 13.9% | 0.454 | 0.792 |

| Residual error | |||||

| Additive error | 352 | 75.3 | 21.4% | 204 | 500 |

| Proportional error | 0.198 | 0.0140 | 7.07% | 0.171 | 0.255 |

RSE (%) = SE/Estimate×100

Wald 95% confidence interval

EC50, exposure producing 50% of Emax; Emax, maximum effect; FAC, product of FPG and GFR; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; RSE, relative standard error; SE, standard error

3.4. PopPK model

First, a total of 534 plasma ipragliflozin concentrations from 43 patients in studies B and C were adopted to develop the prior model of the PopPK model. The structural PK model of ipragliflozin was a 2‐compartment model with first‐order absorption, and IIV of PK parameters were assumed to CL, Vp, and F considering change in OFV and η correlation between parameters.

Next, a total of 3714 trough concentration measurements from 630 patients in studies D, E, F and G were utilized with the developed prior model. In the late phase studies, only trough plasma concentration data were available, therefore, for IIV of PK parameters in the base model, only that of CL/F was assumed because it was unable to appropriately evaluate all η in the prior model. The covariate exploration based on the step‐wise (P < .05) and the backward deletion (P < .001) revealed that GFR, TPRO, TBIL and BSA were significant covariates on CL/F. The fixed effect model for the covariates suggests that CL/F increases with increasing GFR and BSA, and decreases with increasing TPRO and TBIL, as described in Equation 4.

| (4) |

The parameter estimates for the final PopPK model are presented in Table 3. Estimated population means of Ka, CL/F, Vc/F, Q/F and Vp/F were 6.38 h−1, 9.47 L/h, 39.4 L, 6.63 L/h and 68.1 L, respectively. The change in OFV from the base model was −252.044, and the IIV of CL/F decreased from 26.8 to 23.4%, and the shrinkage for η CL/F in the final model was 2%. The residual error in plasma ipragliflozin concentration was 24.8%.

Table 3.

Parameter estimates in the final population pharmacokinetic model

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | RSE (%)† | Lower 95%CI† | Upper 95%CI‡ | CV (%)§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population mean | ||||||

| CL (L/h) | 9.47 | 0.192 | 2.03% | 9.09 | 9.85 | ‐ |

| Vc (L) | 39.4 | 1.41 | 3.58% | 36.6 | 42.2 | ‐ |

| Q/F (L/h) | 6.63 | 0.409 | 6.17% | 5.83 | 7.43 | ‐ |

| Vp (L) | 68.1 | 3.24 | 4.76% | 61.7 | 74.5 | ‐ |

| Ka (h−1) | 6.38 | 0.969 | 15.2% | 4.48 | 8.28 | ‐ |

| GFR effect on CL | 0.233 | 0.0250 | 10.7% | 0.184 | 0.282 | ‐ |

| TPRO effect on CL | −0.417 | 0.0589 | 14.1% | −0.532 | −0.302 | ‐ |

| TBIL effect on CL | −0.0681 | 0.0101 | 14.8% | −0.0879 | −0.0483 | ‐ |

| BSA effect on CL | 0.610 | 0.0950 | 15.6% | 0.424 | 0.796 | |

| Interindividual variability | ||||||

| ω2: CL | 0.0533 | 0.00321 | 6.02% | 0.0470 | 0.0596 | 23.4% |

| Residual error | ||||||

| σ2 | 0.0596 | 0.00161 | 2.70% | 0.0564 | 0.0628 | 24.8% |

RSE (%) = SE/estimate×100

Wald 95% confidence interval

CV (%) = ×100

BSA, body surface area; CL, clearance; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; Ka, first order absorption rate constant; Q/F, apparent intercompartment clearance; RSE, relative standard error; SE, standard error; TBIL, total bilirubin; TPRO, total protein; Vc, apparent volume of distribution in the central compartment; Vp, apparent volume of distribution in the peripheral compartment

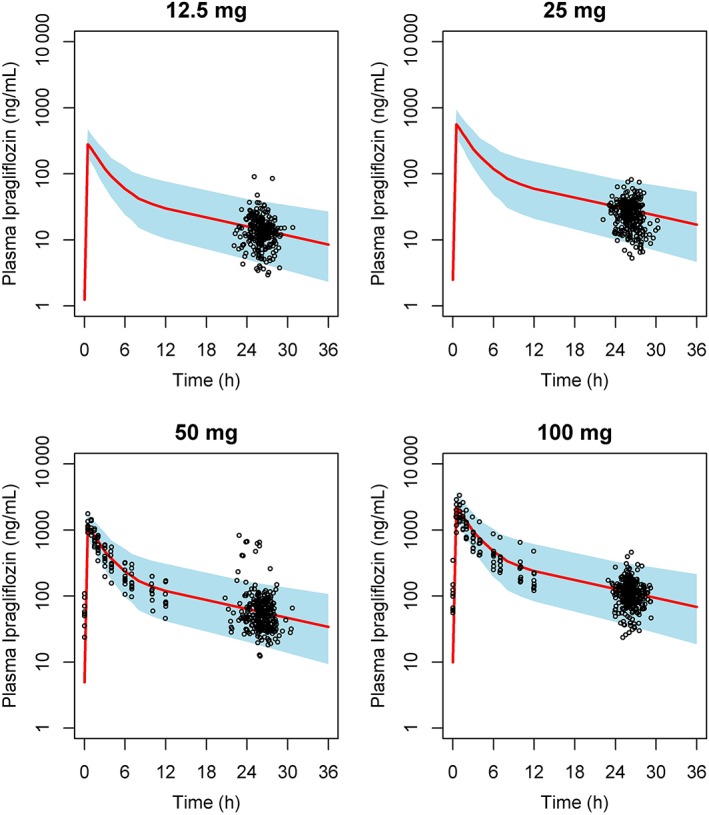

3.5. Model evaluation

In the final PK/PD model, GOF plots suggest acceptable model fittings (Figure S1). The predicted mean and the 95% confidence interval in VPC plot shows that Emax curve is reproducible (Figure S2). In the final PopPK model, GOF plots also suggest acceptable model fittings. The conditional weighted residuals showed no trend against time, visit or dose (Figure S3). And, the model enables to predict individual AUC24h reliably (Figure S4). VPC plots demonstrated that the final PopPK model well reproduced the observed data regardless of dose (Figure 4). The success rate of bootstrap runs was 100% of 300 runs for both the PK/PD model and PopPK models. The summary statistics of the bootstrap estimates were consistent with the parameter estimates of the final model, suggesting the robustness of the estimates.

Figure 4.

Visual prediction checks at steady state in each treatment. Black circles: observations in studies B, C and D. Red line: median of prediction. Blue zone: 95% prediction interval (2.5th – 97.5th percentile)

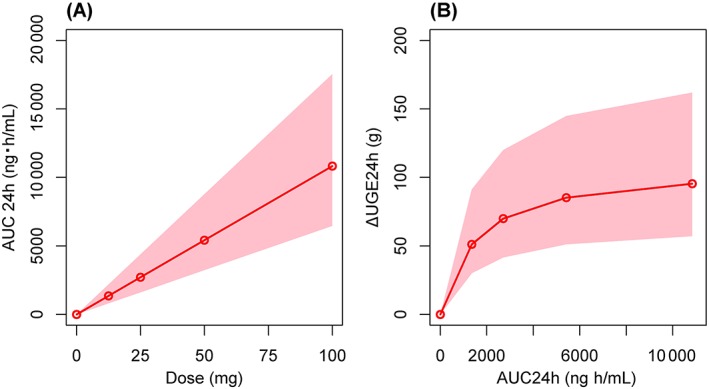

3.6. Simulation

Simulated median and the 95% prediction interval (2.5th–97.5th percentiles) of AUC24h and ΔUGE24h at steady state for each treatment are summarized in Table 4 and Figure 5. The effect of renal function on the exposure of plasma ipragliflozin at steady state was also investigated with once daily administration at 50 mg (Table 5). The simulation suggested a 1.17‐fold increase in AUC24h of ipragliflozin and a 0.76‐fold change in ΔUGE24h in T2DM patients with moderate renal impairment (eGFR: 30 to <60 mL/min/1.73m2) compared to those with normal renal function.

Table 4.

Simulated area under the concentration–time curve from time of dosing to 24 h after administration (AUC24h) of ipragliflozin and change in urinary glucose excretion for 24 hours (ΔUGE24h) at steady‐state in each treatment

| Treatment | AUC24h (ng·h/mL) | ΔUGE24h (g) |

|---|---|---|

| 12.5 mg daily | 1354 (807–2194) | 51 (30–91) |

| 25 mg daily | 2709 (1615–4387) | 70 (42–120) |

| 50 mg daily | 5417 (3229–8775) | 85 (51–145) |

| 100 mg daily | 10834 (6458–17550) | 95 (57–162) |

Median (2.5th–97.5th percentile) are presented for simulated n = 887 data for each treatment

Figure 5.

Simulation of pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics. A, Relationship between area under the concentration–time curve from time of dosing to 24 h after administration (AUC24h) at steady state and ipragliflozin dose. B, Relationship between change in urinary glucose excretion for 24 hours (ΔUGE24h) at steady state and AUC24h. Red line: median of prediction. Pink zone: 95% prediction interval (2.5th–97.5th percentile).

Table 5.

Simulated area under the concentration–time curve from time of dosing to 24 h after administration (AUC24h) of ipragliflozin and change in urinary glucose excretion for 24 hours (ΔUGE24h) at steady‐state after 50 mg daily dose by renal function classification

| Renal function | n | AUC24h (ng h/mL) | ΔUGE24h (g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (eGFR ≥90) | 318 | 5083 (3010–8022) | 86 (66–136) |

| Mild impairment (eGFR 60 to <90) | 466 | 5474 (3318–8835) | 89 (54–154) |

| Moderate impairment (eGFR 30 to <60) | 103 | 5969 (3872–9358) | 65 (29–120) |

Median (2.5th–97.5th percentile) are presented by renal function classification.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate

4. DISCUSSION

The developed PK/PD model described the relationship between the individual plasma ipragliflozin exposure (AUC24h) and ΔUGE24h as a pharmacological effect of ipragliflozin. The PopPK model was developed in order to assess the individual AUC24h in patients with T2DM from sparse PK samples. In a previous publication, we described increase in UGE using an Emax model predicted by AUC24h and the initial excretion level (E0).20 In the model, however, the impact of renal function on UGE was not considered, thus the Emax need to be estimated separately for healthy subjects and patients with T2DM. The new model established in this article provides the mechanism‐based pharmacological effect of SGLT2 inhibitor both healthy subjects and patients with T2DM in 1 model by taking into consideration the individual FPG and GFR.

In healthy individuals, about 180 g of glucose (calculated as the primitive urine production of 180 L/24 h times the normal FPG level of 100 mg/dL) is filtered daily at the renal glomeruli and nearly 100% of filtered glucose is reabsorbed at the renal tubules.19 In other words, both FPG and GFR are determinative factors of UGE. SGLT2 is expressed at the renal proximal tubules and accounts for over 90% of renal glucose reabsorption.21 When the blood glucose level is higher than the maximum capacity of reabsorption (approximately 180 mg/dL), glucose is then excreted into urine. Beyond the threshold, urinary glucose increases in a linear fashion with increasing plasma glucose level.18, 19 SGLT2 inhibitors lower the maximum capacity of glucose reabsorption.

The relationship between FPG, GFR and UGE are clearly indicated by the observed clinical data taken from patients with ipragliflozin in studies A, B and C, which are schematically presented in Figure 3. The figure shows that the threshold value for reabsorption at baseline used in the PK/PD modelling (FPG × GFR = 18 000 or 180 g/24 h) is physiologically adequate if considering the pharmacological effect of SGLT2 inhibitors. As obvious based on the mechanism, the maximum effect on UGE of SGLT2 (ΔUGE24h) never exceeds filtered glucose. Therefore, Emax of ΔUGE24h was parameterized by product of FPG and GFR in this article.

In the PK/PD analysis, the estimated Emax was 140 g/24 h in Japanese T2DM patients with the reference FPG (160 mg/dL) and GFR (90 mL/min). A comparable Emax for empagliflozin (120 g/24 h) was reported in T2DM patients with a mean FPG of 8–9 mmol/L (144–162 mg/dL).22 The Emax of these SGLT2 inhibitors are estimated to be about 40–50% compared to total amount of filtered glucose (288 g: FPG 160 mg/dL × primitive urine production: 180 L/24 h). The absence of complete inhibition of urinary glucose reabsorption was also found even under the condition with almost no SGLT2 activity expected to be remained in empagliflozin and dapagliflozin studies.22, 23 The incomplete inhibition mainly attributes to contribution of reabsorption by SGLT1 expressed in the luminal membrane of the late proximal tubule.24, 25

The final PopPK model indicates fixed effects of BSA, GFR, TPRO and TBIL as statistically significant covariates on ipragliflozin exposure. GFR is thought to be a dominant factor to affect ipragliflozin exposure, whereas the other covariates will cause only 10% or less change in the exposure. Despite the negligible urinary excretion of unchanged ipragliflozin,3, 5 renal function significantly influences ipragliflozin exposure. Both the descriptive comparison of assessed AUC as well as simulation by the final PopPK model indicate about 20% higher exposure in moderate renal impairment patients with T2DM.5 Although GFR has been recognized as a dominant factor affecting ipragliflozin exposure, there is some uncertainty for the application of the model to the T2DM patients with severely impaired renal function who have not been studied in the clinical studies.

By contrast, the PK/PD model suggests that glucose excretion effect almost reaches the maximum level at above 50 mg daily dose of iplagliflozin. Based on the established PK/PD model, it is suggested that any excessive drug effect cannot be expected in renal impairment patients due to the higher exposure caused by renal impairment. In addition, lower GFR in renal impairment patients results in lower urinary filtrated glucose; therefore, the drug effect (ΔUGE24h) by ipragliflozin is lower. Our model well described the result of the lower UGE in renal impairment patients with T2DM found in study C.5 Furthermore, the lower decrease in FPG and HbA1c by ipragliflozin was confirmed in the long‐term study in renal impairment patients (study G).9 Recently, de Winter et al. reported a dynamic PK/PD model for HbA1c decreasing effect of canagliflozin.26 In this report, GFR was a significant covariate of Emax and the outcome was simulated by normalized HbA1c level at baseline. The results are consistent with our findings, and it also supports our assumption that UGE effect by SGLT2 inhibitor must link directly to the clinical outcome.

The developed PK/PD and PopPK models enables to provide individual response of increase in UGE by ipragliflozin. The relationship between the pharmacological effect (ΔUGE) and the long‐term clinical outcomes, i.e. FPG or HbA1c, will be further modelled in future articles.

COMPETING INTERESTS

All authors are employees of Astellas Pharma Inc., Tokyo, Japan.

CONTRIBUTORS

All authors were involved with drafting and revising this article. M.S., A.K. and T.K. planned this analysis, and M.S. conducted the analysis. J.T. contributed data verification and the creation of tables and figures. S.Y. was a lead statistician who was responsible for data handling of each study. K.K. was a study leader for ipragliflozin and contributed to the planning and conduct of the clinical studies. E.U. was a project manager of ipragliflozin and contributed to mapping of the development strategy.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Goodness‐of‐fit plots in the final pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model. Black solid line: the reference line (y = x or y = 0). Red solid line: the locally weighted scatterplot smoothing line.

Figure S2. Visual prediction check in the final pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model. Simulations were performed using the parameter estimates of the final model to generate 1000 datasets. Red solid curve: the median of observed data. Red dashed curves: 95% prediction interval of observed data. Shaded area: 95% confidence intervals for the median and 95% prediction interval by each binning interval.

Figure S3. Goodness‐of‐fit plots in the final population pharmacokinetic model. Black solid line: the reference line (y = x or y = 0). Red solid line: the locally weighted scatterplot smoothing line.

Figure S4. Correlation of area under the concentration–time curves between noncompartment analysis estimations and model predictions. Black solid line: the reference line (y = x or y = 0). Red dash line: the locally weighted scatterplot smoothing line.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Ipragliflozin (Suglat) was co‐developed by Astellas Pharma Inc. and Kotobuki Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. All studies and analyses were funded by Astellas Pharma Inc. The authors thank all of the investigators involved in each trial. Medical writing and editorial support was funded by Astellas and provided by Guy Harris D.O. of DMC Corp. (www.dmed.co.jp) and Mitani K. of EMC KK.

Saito M, Kaibara A, Kadokura T, et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modelling for renal function dependent urinary glucose excretion effect of ipragliflozin, a selective sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, both in healthy subjects and patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85:1808–1819. 10.1111/bcp.13972

REFERENCES

- 1. Jabbour SA, Goldstein BJ. Sodium glucose co‐transporter 2 inhibitors: blocking renal tubular reabsorption of glucose to improve glycaemic control in patients with diabetes. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62(8):1279–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tahara A, Kurosaki E, Yokono M, et al. Pharmacological profile of ipragliflozin (ASP1941), a novel selective SGLT2 inhibitor, in vitro and in vivo. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2012;385(4):423–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kadokura T, Saito M, Utsuno A, et al. Ipragliflozin (ASP1941), a selective sodium‐dependent glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, safely stimulates urinary glucose excretion without inducing hypoglycemia in healthy Japanese subjects. Diabetol Int. 2011;2(4):172–182. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kadokura T, Akiyama N, Kashiwagi A, et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of ipragliflozin in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;106(1):50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ferrannini E, Veltkamp SA, Smulders RA, Kadokura T. Renal glucose handling: impact of chronic kidney disease and sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(5):1260–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kashiwagi A, Kazuta K, Yoshida S, Nagase I. Randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind glycemic control trial of novel sodium‐dependent glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor ipragliflozin in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig. 2014;5(4):382–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kashiwagi A, Kazuta K, Takinami Y, Yoshida S, Utsuno A, Nagase I. Ipragliflozin improves glycaemic control in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: the BRIGHTEN study. Diabetol Int. 2015;6(1):8–18. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kashiwagi A, Kawano H, Kazuta K, et al. Long‐term safety, tolerability and efficacy of ipragliflozin in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus ‐ IGNITE study. Jpn Pharmacol Ther. 2015;43(1):85–100. http://www.lifescience.co.jp/yk/yk15/jan/ab8.html [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kashiwagi A, Takahashi H, Ishikawa H, et al. A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study on long‐term efficacy and safety of ipragliflozin treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and renal impairment: results of the long‐term ASP1941 safety evaluation in patients with type 2 diabetes with renal impairment (LANTERN) study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(2):152–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Data on file, 1941‐CL‐0057, NCT01611428: Absolute bioavailability study. Astellas Pharma Europe BV, 2011.

- 11. Zhang W, Krauwinkel WJ, Keirns J, et al. The effect of moderate hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics of ipragliflozin, a novel sodium glucose co‐transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33(7):489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fujita E, Ushigome F, Suzuki K, et al. Characterization and identification of in vivo and in vitro metabolites of ipragliflozin. Poster W4408 presented at 25th AAPS Annual Meeting. 2011.

- 13. Ushigome F, Kasai Y, Uehara S, et al. Identification of UDP‐glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) isozymes involved in ipragliflozin metabolism in human liver. Poster W4421 presented at 25th AAPS Annual Meeting. 2011.

- 14. Data on file, 1941‐ME‐0009. Validation of a LC‐MS/MS method for the determination of ASP1941 in human plasma. Astellas Pharma Europe B.V., 2007.

- 15. Gisleskog PO, Karlsson MO, Beal SL. Use of prior information to stabilize a population data analysis. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2002;29(5–6):473–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Imai E, Horio M, Nitta K, et al. Estimation of glomerular filtration rate by the MDRD study equation modified for Japanese patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2007;11(1):41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Du Bois D, Du Bois EF. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. Nutrition. 1989;5(5):303–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nair S, Wilding JP. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors as a new treatment for diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(1):34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chao EC, Henry RR. SGLT2 inhibition—a novel strategy for diabetes treatment. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9(7):551–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Freijer J, Krauwinkel WJ, Kadokura T, et al. PK/PD model for ASP1941, a novel SGLT2 inhibitor, characterizes exposure‐urinary glucose excretion relationship in healthy subjects and type2 diabetes mellitus patients. Annual meeting and exposition of AAPS 2010, 12(S2): R6400. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kanai Y, Lee WS, You G, Brown D, Hediger MA. The human kidney low affinity Na+/glucose cotransporter SGLT2. Delineation of the major renal reabsorptive mechanism for D‐glucose. J Clin Invest. 1994;93(1):397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Riggs MM, Seman LJ, Staab A, et al. Exposure‐response modelling for empagliflozin, a sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, in patients with type 2 diabetes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(6):1407–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Komoroski B, Vachharajani N, Feng Y, Li L, Kornhauser D, Pfister M. Dapagliflozin, a novel, selective SGLT2 inhibitor, improved glycemic control over 2 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;85(5):513–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vallon V. The mechanisms and therapeutic potential of SGLT2 inhibitors in diabetes mellitus. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66(1):255–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rieg T, Masuda T, Gerasimova M, et al. Increase in SGLT1‐mediated transport explains renal glucose reabsorption during genetic and pharmacological SGLT2 inhibition in euglycemia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014;306(2):F188–F193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. de Winter W, Dunne A, de Trixhe XW, et al. Dynamic population pharmacokinetic‐pharmacodynamic modelling and simulation supports similar efficacy in glycosylated haemoglobin response with once or twice‐daily dosing of canagliflozin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(5):1072–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harding SD, Sharman JL, Faccenda E, et al. The IUPHAR/BPS guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2018: updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D1091–D1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Alexander SPH, Kelly E, Marrion NV, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: Transporters. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174(Suppl 1):S360–S446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Goodness‐of‐fit plots in the final pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model. Black solid line: the reference line (y = x or y = 0). Red solid line: the locally weighted scatterplot smoothing line.

Figure S2. Visual prediction check in the final pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model. Simulations were performed using the parameter estimates of the final model to generate 1000 datasets. Red solid curve: the median of observed data. Red dashed curves: 95% prediction interval of observed data. Shaded area: 95% confidence intervals for the median and 95% prediction interval by each binning interval.

Figure S3. Goodness‐of‐fit plots in the final population pharmacokinetic model. Black solid line: the reference line (y = x or y = 0). Red solid line: the locally weighted scatterplot smoothing line.

Figure S4. Correlation of area under the concentration–time curves between noncompartment analysis estimations and model predictions. Black solid line: the reference line (y = x or y = 0). Red dash line: the locally weighted scatterplot smoothing line.