Abstract

Background

Oestrosis, caused by the larvae of Oestrus ovis, commonly known as sheep nose bot, is an obligatory cavitary myiasis of sheep and goats. Oestrus ovis is a widespread parasite, but little is known about the prevalence of oestrosis at the global and broad geographical levels. The present study aimed to explore the epidemiology of oestrosis at the global and regional level to estimate prevalences and their associated factors using a systematic approach. This is, to the author’s knowledge, the first meta-analysis of oestrosis in sheep and goats.

Methods

Published articles were obtained from nine electronic databases (PubMed, CAB Abstracts, Web of Science, Scopus, UCB library, Medline, Biosis Citation Index, Indian journals and Google Scholar) reporting the prevalence of O. ovis in sheep and goats from 1970 to 2018. Pooled prevalences were estimated using a random effect meta-analysis model.

Results

Sixty-six studies were eligible, and data from 40,870 sheep and 18,216 goats were used for quantitative analysis. The random effect estimated prevalence of oestrosis at the global level in sheep was 51.15% (95% CI: 42.80–59.51%) and in goats was 42.19% (95% CI: 33.43–50.95%). The pooled prevalence estimates for Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas were 47.85% (95% CI: 36.04–59.66%), 44.48% (95% CI: 33.09–55.87%), 56.83% (95% CI: 48.92–64.74%) and 34.46% (95% CI: 19.90–49.01%), respectively. Heterogeneity (I2 > 80%) was detected in most pooled estimates.

Conclusions

Oestrosis is highly prevalent in many geographical regions of the world, especially in Europe and Africa. Factors that contribute to the pooled prevalence estimate of oestrosis need to be emphasised in any survey to estimate the true prevalence of oestrosis. Furthermore, there is a need for immunisation or implementation of other preventive measures to reduce the burden of oestrosis in sheep and goats and to improve the health and welfare status.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13071-019-3597-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Prevalence, Sheep bot fly, Nasal myiasis, Meta-analysis

Background

Oestrosis is a nasal myiasis, caused by the infestation of larvae of flies belonging to the genus Oestrus (Diptera: Oestridae) and is considered a severe parasitosis in sheep and goats and occasionally in other species of animals [1]. The adult female fly (Oestrus ovis) is commonly known as the sheep nasal bot fly which swarms around the heads of animals. The females are viviparous, and deposit previously hatched larvae (~ 500) directly to the nostril of host animals [2]. These larvae are obligatory parasites of nasal cavities and sinuses. The newly deposited first-stage larvae actively migrate to the nasal passage and attach to the mucous membranes [3]. Later they grow and undergo two moults to become third-stage larvae. During their migration and development, the larvae cause irritation and mechanical damage to the host nasal sinuses. The damaging effect to nasal sinuses can implicate acute clinical problems such as breathing difficulties, profuse nasal discharge and restlessness, which severely impairs the health of the affected animal [4]. Moreover, biomolecules secreted and excreted by larvae induce a local and systemic immune reaction that can exacerbate the situation [5, 6]. Mild infestation is typically asymptomatic but may induce signs of generalised disease including emaciation, which may lead to impaired animal production and consequently economic losses [7]. The infestation period is generally 25–30 days, but it can be longer (up to 10 months) depending on climatic conditions and other variables [3, 8]. The third-stage larvae are later expelled by the host sneezing onto the ground where they pupate and turn into adult flies. However, in some cases, the third-stage larvae fail to eject from the nasal sinuses and die. This may lead to septic sinusitis resulting in the death of animal [9]. The host response to oestrosis and larval burden are related to several factors such as susceptibility of host species, chronobiology of O. ovis at a particular geographical region and routine animal management practices [10]. Adult flies cause disturbances in flocks and substantial losses in animal production are particularly associated with the larval development of the parasite [11]. Adding to these issues, this parasite is difficult to control in the environment and there is a significant disparity in the therapeutic response of sheep and goats [12].

Oestrosis is primarily a myiasis of sheep and goats; however, there have been widespread reports of human infestation [13–15]. It is the most common cause of human ophthalmomyiasis and is typically occurs in shepherds and farmers [16]. Although it has also been reported in patients who have no association with animal husbandry and are far from any farming zone, the number of cases is limited [17, 18]. A high prevalence of oestrosis in sheep and goats in a geographical region may potentially increase the risk of zoonosis and may influence the occurrences of human infection.

Understanding the distribution of oestrosis and associated risk factors is essential to improving animal health. The disease is distributed worldwide and widespread in many regions of the world. An almost full-scale of prevalence estimates ranging between 5.88–100% of oestrosis in sheep and goats has been reported worldwide [19–23]. This inconsistent estimate in various geographical locations is plausible due to an aggregated distribution of the parasite in particular geographical areas and climatic conditions, methods for identifying the disease, the origin of the sample and sampling strategy, study duration and studied species of animal. An overview of knowledge on the geographical distribution and burden of oestrosis in sheep and goats will offer a better understanding of its impacts on animal production and prevent the spread of disease to humans. Therefore, this study aimed to estimate the global prevalence of oestrosis in sheep and goats and to assess the potential factors that contribute to the variability in the prevalence and distribution of the disease using a systematic approach.

Methods

The study was conducted according to the guidelines provided by PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) for systemic review and meta-analysis. The PRISMA 2009 checklist (Additional file 1: Table S1) was followed to ensure the inclusion of relevant information and maintain study standard.

Literature search

A systemic search strategy was used to identify all published articles reporting the prevalence of O. ovis in sheep and goats. Published works of literature were searched in nine electronic databases: PubMed, CAB Abstracts, Web of Science, Scopus, UCB library, Medline, Biosis Citation Index, Indian journals and Google Scholar, published between January 1970 and March 2018. Searches of the first seven listed databases were undertaken on 30th of March 2018, and the last two on 31st of March 2018. The search terms were categorised into descriptive, population and outcome as described before by Islam et al. [24]. The modified search terms are presented in Table 1. Search field option was selected as “All Fields”. The “descriptive term”, “population term” and “outcome term” were combined using the Boolean operator “AND”. Search terms were adjusted as per specification and minor differences in syntax rules of individual databases.

Table 1.

Algorithm for electronic database search to find published reports on the prevalence of oestrosis in sheep and goats

| Search term | Boolean keywords |

|---|---|

| Descriptive term | Prevalence OR incidence OR frequency OR occurrence OR detection OR identification OR isolation OR characterisation OR investigation OR survey OR rate |

| Population term | Oestrus ovis OR O. ovis OR sheep nasal bot OR sheep botfly OR bot fly larva OR nasal myiasis OR oestrosis OR estrosis OR oestrus myiasis OR O. ovis myiasis OR botfly encephalitis |

| Outcome term | Goat OR doe OR buck OR caprine OR ovine OR sheep OR ram OR ewe OR small ruminant |

The search optimisation was performed for articles published in the English language. The reference list of all retrieved items was searched manually in triplicate to identify all eligible studies and to ensure that databases searches have missed no reports.

Selection of studies

Articles were considered eligible for meta-analysis based on the following criteria: published between January 1970 and March 2018; full-text article; English language; any country of the world; reported as animal level prevalence data; studied population is sheep or goat or both; cross-sectional, case-control, longitudinal and cohort studies. Articles were excluded if prevalence data were not reported, species other than sheep or goat, case study, experimental trial and materials other than the English language.

Quality of the studies

Selected studies were evaluated for quality of reporting and selection for bias using a quality appraisal checklist [25, 26] (Additional file 2: Text S1, Figure S1).

Data extraction

The following data were extracted on a spreadsheet where possible from each eligible article: author, year of publication, country, region/province, continent, study duration, host, breed, origin of sample, method of detection/diagnosis, population, positive, prevalence, season when the prevalence was highest, ambient temperature during the peak prevalence season, specific risk (sex, age, coat colour), mean larval burden and the highest number of larvae per head. Overall, data from 59,086 animals (sheep and goats) of various geographical locations were analysed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of 66 studies included in this meta-analysis to investigate the pooled prevalence of oestrosis in sheep and goats

| Reference | Year | Country | Study duration (months) | Host | Sample origin | Detection method | No. of samples | Positive n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benakhla et al. [20] | 2004 | Algeria | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 313 | 211 (67.41) |

| Attindehou et al. [21] | 2012 | Benin | 6 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 256 | 90 (35.16) |

| Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 224 | 43 (19.20) | ||||

| Amin et al. [22] | 1997 | Egypt | na | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 1200 | 104 (8.67) |

| Osman [29] | 2010 | Egypt | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 623 | 217 (34.83) |

| Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 357 | 83 (23.25) | ||||

| Ramadan et al. [43] | 2013 | Egypt | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 3132 | 360 (11.49) |

| Alem et al. [30] | 2010 | Ethiopia | 5 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 369 | 349 (94.58) |

| Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 431 | 381 (88.40) | ||||

| Bekele et al. [44] | 1995 | Ethiopia | 16 | Sheep | Farm | Necropsy | 376 | 23 (6.12) |

| Gebremedhin [31] | 2011 | Ethiopia | 6 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 311 | 217 (69.77) |

| Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 243 | 115 (47.33) | ||||

| Yilma & Genet [32] | 2000 | Ethiopia | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 248 | 192 (77.42) |

| Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 258 | 188 (72.87) | ||||

| Gabaj et al. [33] | 1993 | Libya | 5 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 1489 | 336 (22.57) |

| Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 320 | 59 (18.44) | ||||

| Negm-Eldin [34] | 2015 | Libya | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 180 | 93 (51.67) |

| Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 120 | 34 (28.33) | ||||

| Pandey & Ouhelli [45] | 1984 | Morocco | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 120 | 83 (69.17) |

| Oniye [46] | 2006 | Nigeria | 6 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 116 | 72 (62.07) |

| Horak [47] | 1977 | South Africa | 24 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 542 | 398 (73.43) |

| Horak [1] | 2005 | South Africa | 12 | Sheep | Farm | Necropsy | 193 | 103 (53.37) |

| Goat | Farm | Necropsy | 96 | 58 (60.42) | ||||

| Pandey [48] | 1989 | Zimbabwe | 13 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 507 | 111 (21.89) |

| Biu & Nwosu [79] | 1999 | Nigeria | 12 | Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 4000 | 2150 (53.75) |

| Horak & Butt [80] | 1977 | South Africa | 13 | Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 130 | 96 (73.85) |

| Saleem et al. [49] | 2017 | India | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 120 | 119 (99.17) |

| Sharma et al. [50] | 2012 | India | na | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 128 | 25 (19.53) |

| Dhishonin et al. [51] | 2017 | India | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 143 | 9 (6.29) |

| Jagannath et al. [35] | 1989 | India | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 520 | 464 (89.23) |

| Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 263 | 219 (83.27) | ||||

| Pathak [36] | 1992 | India | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 384 | 312 (81.25) |

| Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 466 | 249 (53.43) | ||||

| Dehghani et al. [37] | 2012 | Iran | 6 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 5934 | 1347 (22.70) |

| Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 1802 | 409 (22.70) | ||||

| Shoorijeh et al. [38] | 2010 | Iran | 13 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 2002 | 994 (49.65) |

| Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 1998 | 261 (13.06) | ||||

| Shoorijeh et al. [52] | 2009 | Iran | 13 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 2002 | 995 (49.70) |

| Tavassoli et al. [53] | 2012 | Iran | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 402 | 122 (30.35) |

| AL-Ubeidi et al. [54] | 2017 | Iraq | 3 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 133 | 72 (54.14) |

| Abo-Shehada et al. [55] | 2000 | Jordan | 17 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 417 | 242 (58.03) |

| Othman [56] | 2009 | Palestine | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 335 | 181 (54.03) |

| Alahmed [19] | 2000 | Saudi Arabia | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 544 | 32 (5.88) |

| Alikhan et al. [57] | 2018 | Saudi Arabia | na | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 1334 | 400 (29.99) |

| Hanan [58] | 2013 | Saudi Arabia | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 480 | 257 (53.54) |

| Arslan et al. [59] | 2009 | Turkey | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 387 | 156 (40.31) |

| Ipek & Altan [39] | 2017 | Turkey | 2 | Sheep | Abattoir | Semi-nested PCR | 158 | 133 (84.18) |

| Goat | Abattoir | 26 | 10 (38.46) | |||||

| Sheep | Abattoir | Rhinoscopy | 158 | 104 (65.82) | ||||

| Goat | Abattoir | 26 | 10 (38.46) | |||||

| Karatepe et al. [60] | 2014 | Turkey | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 364 | 82 (22.53) |

| Özdal et al. [61] | 2016 | Turkey | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 328 | 127 (38.72) |

| Uslu & Dik [62] | 2006 | Turkey | 13 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 624 | 368 (58.97) |

| Rahman & Karim [81] | 1989 | Bangladesh | 12 | Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 705 | 175 (24.82) |

| Huq [82] | 1983 | Bangladesh | 15 | Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 600 | 114 (19.00) |

| Jumde & Dixit [83] | 2012 | India | na | Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 247 | 194 (78.54) |

| Shoorijeh et al. [84] | 2011 | Iran | 13 | Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 1998 | 261 (13.06) |

| Abo-Shehada et al. [85] | 2003 | Jordan | 13 | Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 520 | 126 (24.23) |

| Dorchies et al. [40] | 2000 | France | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 631 | 274 (43.42) |

| Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 672 | 191 (28.42) | ||||

| Yilma & Dorchies [63] | 1991 | France | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 555 | 361 (65.05) |

| Bauer et al. [64] | 2002 | Germany | 24 | Sheep | Farm | ELISA | 1497 | 753 (50.30) |

| Papadopoulos et al. [7] | 2006 | Greece | na | Sheep | Mixed flock | ELISA | 397 | 193 (48.61) |

| Goat | Mixed flock | ELISA | 335 | 58 (17.31) | ||||

| Papadopoulos et al. [23] | 2001 | Greece | 12 | Sheep | Mixed flock | ELISA | 300 | 300 (100) |

| Goat | Mixed flock | ELISA | 500 | 212 (42.40) | ||||

| Papadopoulos et al. [41] | 2010 | Greece | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 292 | 126 (43.15) |

| Goat | Abattoir | Necropsy | 158 | 120 (75.95) | ||||

| Caracappa et al. [65] | 2000 | Italy | 24 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 841 | 469 (55.77) |

| Scala et al. [66] | 2001 | Italy | 12 | Sheep | Free-ranging flocks | Necropsy | 566 | 514 (90.81) |

| Scala et al. [3] | 2002 | Italy | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | ELISA and necropsy | 443 | 327 (73.81) |

| Cozma et al. [67] | 2010 | Romania | 6 | Sheep | Farm | Necropsy and skin sensitivity test | 280 | 140 (50.00) |

| Daniela [42] | 2008 | Romania | 9 | Sheep | Mixed flock | Necropsy | 84 | 57 (67.86) |

| Goat | Mixed flock | Necropsy | 51 | 22 (43.14) | ||||

| Alcaide et al. [68] | 2005 | Spain | 9 | Sheep | Farm | ELISA and necropsy | 276 | 218 (78.99) |

| Alcaide et al. [69] | 2005 | Spain | 23 | Sheep | Farm | ELISA | 5878 | 4070 (69.24) |

| Gracia et al. [70] | 2010 | Spain | 12 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 120 | 101 (84.17) |

| Gracia et al. [71] | 2006 | Spain | na | Sheep | Pasture and indoor | Necropsy | 20 | 14 (70.00) |

| Paredes-Esquivel et al. [72] | 2009 | Spain | 2 | Sheep | Free ranging flocks | Necropsy | 206 | 173 (83.98) |

| Paredes-Esquivel et al. [73] | 2012 | Spain | 13 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 554 | 255 (46.03) |

| Alcaide et al. [86] | 2005 | Spain | 23 | Goat | Farm | ELISA | 1590 | 717 (45.09) |

| 9 | Goat | Farm | Necropsy | 80 | 28 (35) | |||

| Carvalho et al. [74] | 2015 | Brazil | 80 | Sheep | Farm | Necropsy | 71 | 12 (16.90) |

| Silva et al. [75] | 2013 | Brazil | 8 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 139 | 19 (13.67) |

| Silva et al. [76] | 2012 | Brazil | 36 | Sheep | Farm | Necropsy | 72 | 36 (50.00) |

| Hidalgo et al. [77] | 2015 | Chile | 4 | Sheep | Abattoir | Necropsy | 87 | 53 (60.92) |

| Murguía et al. [78] | 2000 | Mexico | na | Sheep | Farm | Thin layer immune assay test | 689 | 229 (33.24) |

Abbreviations: ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; na, not mentioned

Data analysis

All obtained data were entered and sorted in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Prevalence was estimated by the number of positive animals divided by the total number of animals. Only the crude estimate of prevalence was used and their 95% confidence interval (CI). The CI was calculated using the standard formula for a proportion (p): , where n is the studied population size [24]. In circumstances where the higher limit of CI exceeded 100, the value was settled to 100 to avoid > 100% prevalence. Data were analysed using STATA v.11.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The meta-analysis was performed using the STATA command “metan”. The percentage of heterogeneity across studies that is due to variation rather than chance was estimated by interpreting the I2 statistic value and Cochran’s Q (represented as χ2 and P-values) [27]. The I2 values of 25, 50 and 75% were considered as low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively [27]. Due to a high degree of heterogeneity between studies the random effect model was selected for summary statistics. Furthermore, the potential sources of heterogeneity were investigated by subgroup analysis. Five potential sources of heterogeneity were examined: continent, country, species, origin of the sample and the method of detection. For constructing a forest plot, data of each continent were analysed separately with the stratified command “by” for the variables. The results are presented as prevalence percentage with 95% CI. Assessment of small study effects was determined using two funnel plots, and the sources of funnel plots asymmetry were also tested to identify the publication bias by Egger’s test [28].

Additionally, analysis of climatic data was performed by extracting the ambient temperature data during the peak prevalence season directly from the prospective articles or, where the peak prevalence season was reported but temperature was not mentioned, from the national weather databases. Only the crude estimate of average temperature was used and their minimum temperature (Tmin) and maximum temperature (Tmax). Average ambient temperature was calculated using the formula: (Tmax + Tmin)/2. Similar to other variables, due to a high degree of heterogeneity the random effect model was selected for summary statistics. In circumstances where the average ambient temperature value was a proportion, the value was rounded to the nearest number using the ceiling and floor functions of Microsoft Excel 2016. Three potential sources of heterogeneity were examined: continent, country and temperature range. For constricting the forest plot, data of continent, country and temperature sub-group were analysed separately. The results are presented as degree Celsius (°C) with 95% CI of the mean.

Results

Search results and eligible studies

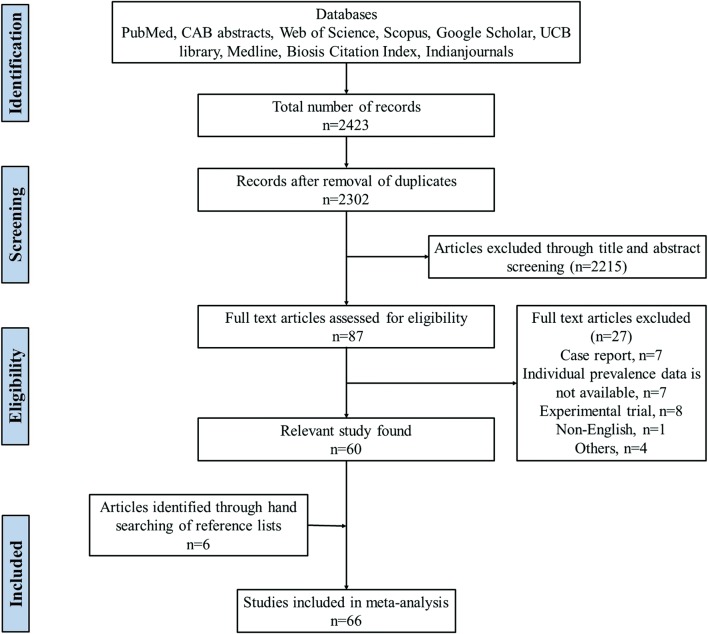

Figure 1 shows the search results. In the initial search on selected databases, 2423 potential articles were identified. After screening, a total of 87 eligible articles were found of which 27 articles were excluded due to following reasons: case report (n = 7); individual prevalence data not available (n = 7); experimental trial (n = 8); article other than the English language (n = 1); and others (n = 4). The list of excluded articles along with reasons for their exclusion is provided in Additional file 3: Text S2. A total of 66 eligible articles were used for meta-analysis (Additional file 4: Text S3). Among the selected articles, 18 articles reported the prevalence of oestrosis in both sheep and goats [1, 7, 21, 23, 29–42], 40 articles in sheep [3, 19, 20, 22, 43–78] and 8 articles reported only in goats [79–86]. Based on the origin of samples, 50 studies were from abattoirs [3, 19–22, 29–41, 43, 45–63, 65, 70, 73, 75, 77, 79–85], 10 from farms [1, 44, 64, 67–69, 74, 76, 78, 86], 3 from free ranging flocks [66, 71, 72] and 3 from mixed flocks [7, 23, 42]. Based on the method of diagnosis, 56 studies used necropsy [1, 19–22, 29–38, 40–63, 65, 66, 70–77, 79–85], 4 used ELISA [7, 23, 64, 69] and 6 used combined or other methods [3, 39, 67, 68, 78, 86]. A description of the characteristics of each included study is shown in Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the selection of eligible studies for inclusion in the meta-analysis

Continents and countries

All included studies on sheep and goats represent data from 5 continents, covering 26 countries of the world. The highest number of articles (n = 25) were from Asia covering 8 countries: India (n = 6), Iran (n = 5), Turkey (n = 5), Saudi Arabia (n = 3), Bangladesh (n = 2), Jordan (n = 2), Iraq (n = 1) and Palestine (n = 1). The second highest was from both Africa and Europe, with the same number of articles from each continent (n = 18). Countries within Africa contributed as follows: Ethiopia (n = 4), Egypt (n = 3), South Africa (n = 3), Libya (n = 2), Nigeria (n = 2), Algeria (n = 1), Benin (n = 1), Morocco (n = 1) and Zimbabwe (n = 1). European countries reported as follows: Spain (n = 7), Greece (n = 3), Italy (n = 3), France (n = 2), Romania (n = 2) and Germany (n = 1). Four articles were from South America: Brazil (n = 3) and Chile (n = 1). One article was from North America: Mexico (n = 1).

Prevalence estimates

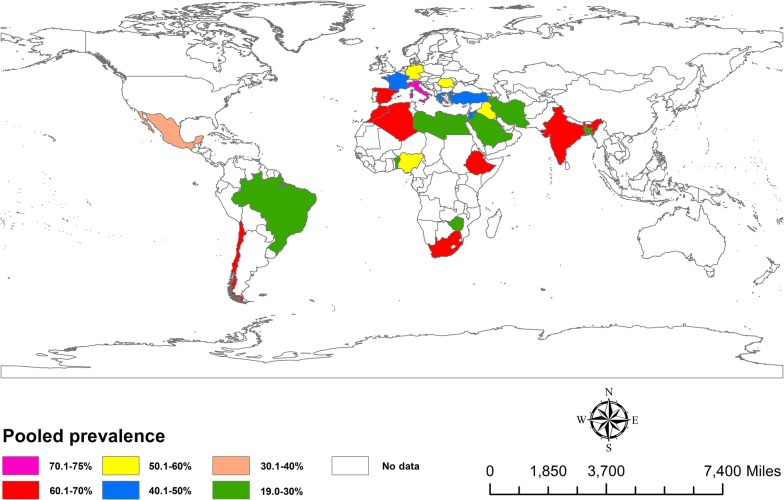

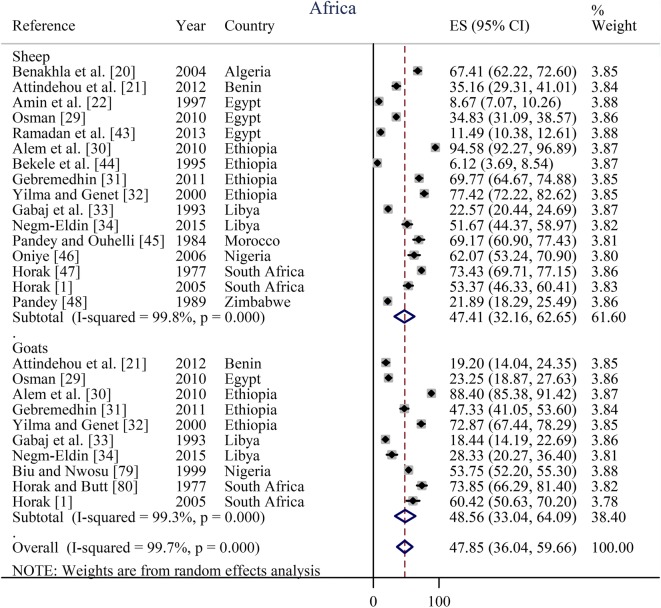

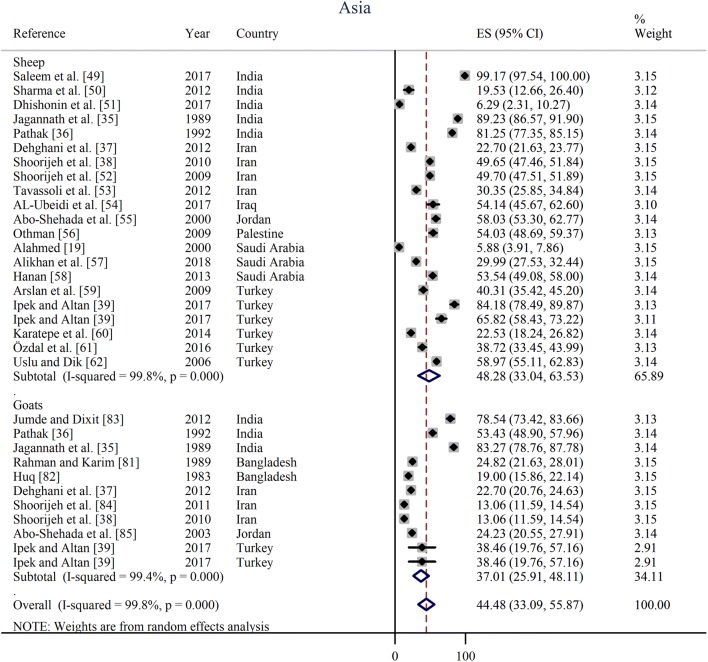

On the basis of the global burden of oestrosis in sheep, the estimated prevalence ranged from 34.45% (95% CI: 19.90–49.01%) to 63.69% (95% CI: 56.08–71.30%) with considerable heterogeneity (I2= 96.7%, P < 0.0001). The random effect estimated global prevalence in sheep was 51.15% (95% CI: 42.80–59.51%) (Table 3). Likewise, the estimated prevalence of oestrosis in goats ranged from 37.01% (95% CI: 25.91–48.11%) to 48.56% (95% CI: 33.04–64.09%) with high heterogeneity (I2= 99.4%, P < 0.0001). The random effect estimated global prevalence in goats was 42.19% (95% CI: 33.43–50.95%) (Table 4). Overall, the global pooled estimated prevalence of oestrosis in sheep and goats was 48.25% (95% CI: 41.82–54.67%) with substantial heterogeneity (I2= 99.7%, P < 0.0001) (Table 5). The global estimated pooled prevalence of oestrosis in sheep and goats by country are shown in Fig. 2.

Table 3.

Estimated pooled prevalence of oestrosis in sheep by world region

| World region | No. of studies | No. of sheep sampled | No. of positive sheep | Pooled estimate % | 95% CI | Heterogeneity (χ2) | I2 (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global estimate | 58 | 40,870 | 18,194 | 51.15 | 42.80–59.51 | 26,703.21 | 99.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Africa | 16 | 9975 | 2959 | 47.41 | 32.16–62.65 | 6591.58 | 99.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Asia | 20 | 16,897 | 6541 | 48.28 | 33.04–63.53 | 12,879.06 | 99.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Europe | 17 | 12,940 | 8345 | 63.69 | 56.08–71.30 | 1108.77 | 98.6 | < 0.0001 |

| North and South America | 5 | 1058 | 349 | 34.45 | 19.90–49.01 | 76.80 | 94.8 | < 0.0001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; χ2, Cochran’s Q Chi square; I2, inverse variance index

Table 4.

Estimated pooled prevalence of oestrosis in goats by world region

| World region | No. of studies | No. of goats sampled | No. of positive goats | Pooled estimate % | 95% CI | Heterogeneity (χ2) | I2 (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global estimate | 26 | 18,216 | 6583 | 42.19 | 33.43–50.95 | 5277.62 | 99.5 | < 0.0001 |

| Africa | 10 | 6179 | 3207 | 48.56 | 33.04–64.09 | 1247.18 | 99.3 | < 0.0001 |

| Asia | 10 | 8651 | 2028 | 37.01 | 25.91–48.11 | 1656.08 | 99.4 | < 0.0001 |

| Europe | 6 | 3386 | 1348 | 40.93 | 28.93–52.92 | 291.83 | 97.9 | < 0.0001 |

| North and South Americaa | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

aNo records of goat oestrosis from North or South America

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; χ2, Cochran’s Q Chi square; I2, inverse variance index

Table 5.

Pooled prevalences and estimated sources of heterogeneity in the prevalence of oestrosis in sheep and goats

| Variable | Population | Pooled estimate prevalence (%) | 95% CI | Heterogeneity (χ2) | I2 (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| World region | ||||||

| Global estimate | 59,086 | 48.25 | 41.82–54.67 | 33,292.86 | 99.7 | < 0.0001 |

| Africa | 16,154 | 47.85 | 36.04–59.66 | 9371.58 | 99.7 | < 0.0001 |

| Asia | 25,548 | 44.48 | 33.09–55.87 | 17,688.62 | 99.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Europe | 16,326 | 56.83 | 48.92–64.74 | 2380.45 | 99.1 | < 0.0001 |

| North and South America | 1058 | 34.46 | 19.90–49.01 | 89.80 | 95.5 | < 0.0001 |

| Age | ||||||

| Young (≤ 1 year) | 18,188 | 38.30 | 27.21–49.38 | 8266.67 | 99.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Adult (> 1 year) | 18,188 | 49.53 | 38.02–61.03 | 7006.91 | 99.7 | < 0.0001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 12,533 | 39.55 | 27.73–51.36 | 2288.98 | 99.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Female | 12,533 | 48.74 | 31.16–66.33 | 6151.18 | 99.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Origin of sample | ||||||

| Abattoir | 49,124 | 47.72 | 40.53–44.90 | 29,650.45 | 99.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Farm | 9962 | 50.78 | 36.49–65.07 | 2658.55 | 99.5 | < 0.0001 |

| Method of detection | ||||||

| Necropsy | 46,398 | 47.16 | 39.81–54.51 | 29,999.03 | 99.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Serology | 11,075 | 50.87 | 39.09–62.65 | 995.73 | 99.2 | < 0.0001 |

| Other | 1613 | 56.18 | 37.80–74.57 | 360.69 | 98.3 | < 0.0001 |

| Study duration (months) | ||||||

| ≤ 6 | 12,200 | 49.19 | 37.73–60.64 | 3046.99 | 99.4 | < 0.0001 |

| > 6 to ≤ 12 | 19,908 | 52.23 | 40.57–63.89 | 18,701.79 | 99.8 | < 0.0001 |

| > 12 | 22,219 | 41.78 | 30.37–53.19 | 6898.52 | 99.7 | < 0.0001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; χ2, Cochran’s Q Chi square; I2, inverse variance index

Fig. 2.

Estimated prevalence of oestrosis caused by Oestrus ovis in sheep and goats in different countries of the world from 1970 to 2018. The prevalence estimate is based on a meta-analysis of 66 studies comprising 59,086 sheep and goats. The map was produced using ArcGIS v.10.3.1 (Esri, Redlands, CA, USA)

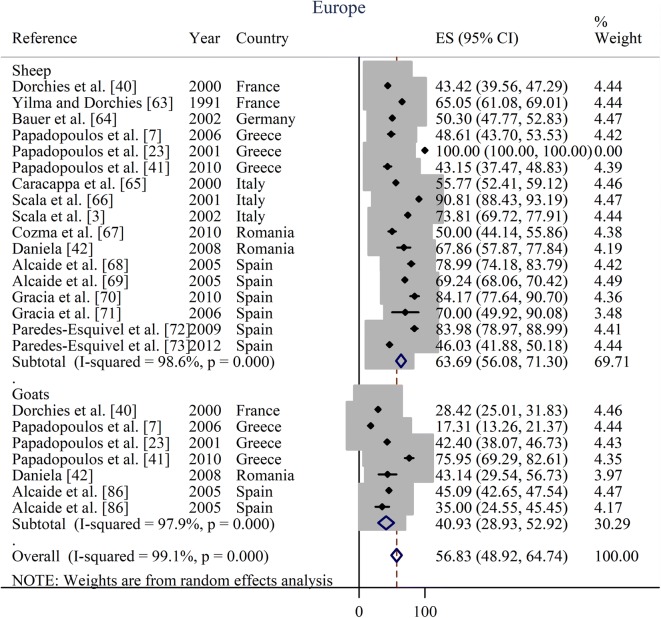

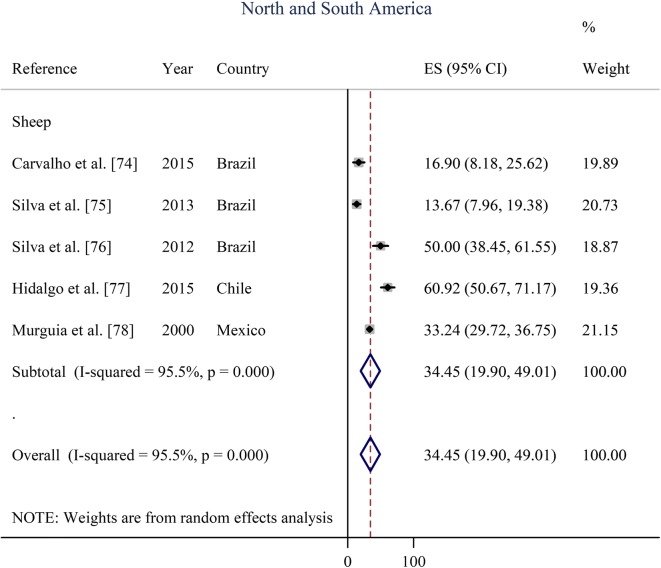

Prevalence estimates from individual contributing studies according to world region are outlined in Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6 and Table 2. The lowest individual prevalence of oestrosis in sheep was reported as 5.88% (95% CI: 3.91–7.86%) in Saudi Arabia [19] and the highest individual prevalence was reported as 100% (95% CI: 100–100%) in Greece [23]. In goats, the lowest individual prevalence was reported as 13.06% (95% CI: 11.59–14.54%) in Iran [84] and the highest individual prevalence was reported as 88.40% (95% CI: 85.38–91.42%) in Ethiopia [30]. The longest study duration was 80 months [74] while the shortest study duration was 2 months [39].

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of the prevalence estimates of oestrosis caused by Oestrus ovis in sheep and goats amongst studies conducted in Africa

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of the prevalence estimates of oestrosis caused by Oestrus ovis in sheep and goats amongst studies conducted in Asia

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of the prevalence estimates of oestrosis caused by Oestrus ovis in sheep and goats amongst studies conducted in Europe

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of the prevalence estimates of oestrosis caused by Oestrus ovis in sheep amongst studies conducted in North and South America. Note that there are no data on oestrus in goats between 1970 and 2018 in both North and South America

Age and sex-related prevalence are summarised in Table 5. For determining the age effect, two age groups were selected. The estimated pooled prevalence of oestrosis was 49.53% (95% CI: 38.02–61.03%) in adult animals and 38.30% (95% CI: 27.21–49.38%) in young animals. The overall estimated pooled prevalence of oestrosis was 48.74% (95% CI: 31.16–66.33%) in female animals and 39.55% (95% CI: 27.73–51.36%) in male animals.

Pooled prevalence based on the origin of samples, methods of detection and study duration are shown in Table 5. The overall estimated pooled prevalence of oestrosis in sheep and goats slaughtered in abattoirs was 47.72% (95% CI: 40.53–44.90%) while the prevalence in farmed animals was 50.78% (95% CI: 36.49–65.07%). Prevalence was 47.16% (95% CI: 39.81–54.51%), 50.87% (95% CI: 39.09–62.65%) and 56.18% (95% CI: 37.80–74.57%) by necropsy, serology and others methods of diagnosis, respectively, to detect oestrosis in sheep and goats. Studies conducted for > 6 to ≤ 12 months had higher prevalence 52.23% (95% CI: 40.57–63.89%) than the study conducted for ≤ 6 months [49.19% (95% CI: 37.73–60.64%)] and > 12 months [41.78% (95% CI: 30.37–53.19%)].

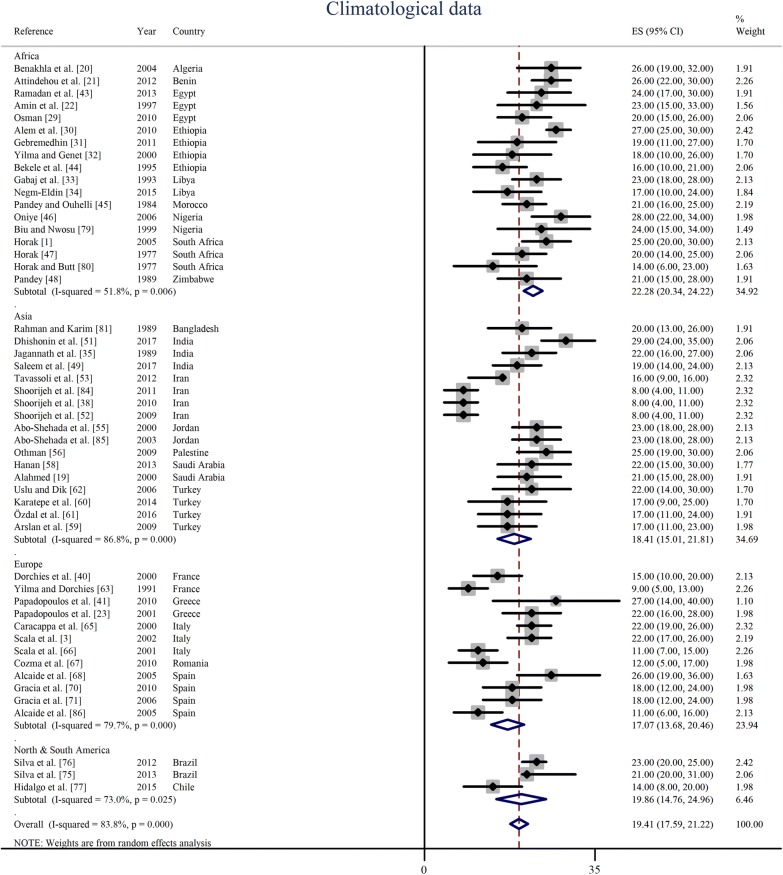

Effect of ambient temperature

Peak prevalence season of oestrosis in sheep and goats and ambient environmental temperature during that particular period of the year was obtained from 50 articles representing 23 countries of the world. The average ambient temperature during the peak infestation period was 22 °C (95% CI: 20–24 °C) in Africa, 18 °C (95% CI: 15–22 °C) in Asia, 17 °C (95% CI: 14–20 °C) in Europe and 20 °C (95% CI: 15–25 °C) in South America. Overall, the random effect estimated pooled global ambient temperature was 19 °C (95% CI: 18–21 °C) with significant heterogeneity (I2= 83.8%, P < 0.0001). The lowest temperature at which the peak prevalence of oestrosis observed was 10 °C (95% CI: 6–14 °C) in Iran while the highest temperature at which the peak prevalence found was 27 °C (95% CI: 22–32 °C) in Nigeria. The ambient temperature at which the peak prevalence was observed are shown in Fig. 7 and country-wise results in Table 6. Results of sub-group analysis of peak prevalence estimates based on ambient temperature are shown in Additional file 5: Figure S2.

Fig. 7.

Ambient environmental temperature at which the peak prevalence of oestrosis found in sheep and goats at different continents and countries of the world

Table 6.

Estimated pooled temperature at which the peak prevalence of oestrosis reported in sheep and goats in different world regions

| Country | T (°C) | 95% CI | Heterogeneity (χ2) | I2 (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | 26 | 19–32 | 0 | – | – |

| Bangladesh | 20 | 13–26 | 0 | – | – |

| Benin | 26 | 22–30 | 0 | – | – |

| Brazil | 22 | 20–25 | 0.42 | 0.0 | 0.516 |

| Chile | 14 | 7–20 | 0 | – | – |

| Egypt | 22 | 18–26 | 0.92 | 0.0 | 0.632 |

| Ethiopia | 20 | 14–27 | 17.29 | 82.6 | 0.001 |

| France | 12 | 6–18 | 3.37 | 70.4 | 0.066 |

| Greece | 23 | 17–28 | 0.47 | 0.0 | 0.494 |

| India | 23 | 17–29 | 7.16 | 72.1 | 0.028 |

| Iran | 10 | 6–14 | 15.05 | 80.1 | 0.002 |

| Italy | 18 | 11–26 | 19.67 | 89.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Jordan | 23 | 19–27 | 0 | 0.0 | 1.000 |

| Libya | 20 | 15–26 | 1.87 | 46.5 | 0.172 |

| Morocco | 21 | 16–25 | 0 | – | – |

| Nigeria | 27 | 22–32 | 0.49 | 0.0 | 0.485 |

| Palestine | 25 | 19–30 | 0 | – | – |

| Romania | 12 | 6–18 | 0 | – | – |

| Saudi Arabia | 22 | 17–27 | 0.04 | 0.0 | 0.843 |

| South Africa | 20 | 14–26 | 5.15 | 61.2 | 0.076 |

| Spain | 18 | 12–23 | 9.93 | 69.8 | 0.019 |

| Turkey | 18 | 15–21 | 1.22 | 0.0 | 0.749 |

| Zimbabwe | 21 | 15–28 | 0 | – | – |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; χ2, Cochran’s Q Chi square; I2, inverse variance index; –, no interaction due to having single study; T, pooled average temperature

Source of heterogeneity

Six sources of heterogeneity in prevalence of oestrosis in sheep and goats were observed. These were: world region (P < 0.0001); age (P < 0.0001); sex (P < 0.0001); origin of the sample (P < 0.0001); method of detection (P < 0.0001); and study duration (P < 0.0001) (Table 5).

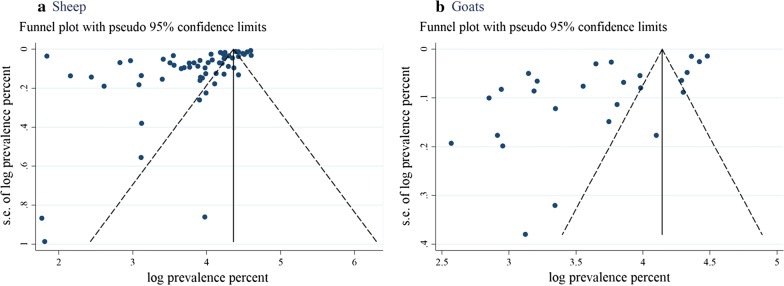

Overall, there was a high level of heterogeneity in most pooled prevalence estimates (I2 > 80%). The expanse of publication bias in the selected studies was measured separately for sheep (Fig. 8a) and goats (Fig. 8b). Both funnel plots appeared with the asymmetrical appearance with a gap in the right bottom side of the graph and many points fall outside of the funnels in the left side, indicating publication bias. The estimated bias co-efficient in sheep was 4.56 (95% CI: 4.45–4.67) with a standard error 0.055 providing a P-value of < 0.0001 while the estimated bias coefficient in goats was 4.34 (95% CI: 4.07–4.61) with a standard error 0.129 and a P-value of < 0.0001. Bias assessment checklist and scores of individual studies are shown in Additional file 2: Table S2.

Fig. 8.

Funnel plot for examination of publication bias of the prevalence estimates of oestrosis in sheep (a) and goat (b). Abbreviation: s.e., standard error

Discussion

This study summarises the prevalence of oestrosis in sheep and goats in global and regional levels based on a large population (n = 59,086; sheep: 40,870 and goats: 18,216) derived from 26 countries of five continents of the world that enabled the assessment of reliable prevalence estimates according to the study objectives. To the best of author’s knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis of the global prevalence of oestrosis in sheep and goats.

The global prevalence of oestrosis in sheep and goats is high with an estimated pooled prevalence of 48.25% (95% CI: 41.82–54.67%) across 66 published reports. Around the globe, Europe had the highest disease burden 56.83% (95% CI: 48.92–64.74%) and North and South America had the lowest disease burden at 34.46% (95% CI: 19.90–49.01%). Mexico was the only country of North America that reported oestrosis in sheep; therefore, data for Mexico were compiled with the data from South American countries to estimate the pooled prevalence for meaningful analysis. There could be several reasons for the high prevalence of oestrosis in sheep and goats such as a pasture-based farming system, the presence of favourable climatic conditions for flies and a limited level of flock/herd monitoring as farmers usually provide less attention to individual sheep and goats as they do for other farm animals. Moreover, many studies were conducted in slaughterhouses in different countries which quickly revealed the infestation of O. ovis larvae from the nasal sinuses of sheep and goats [20–22].

The reported ambient environmental temperature at which the peak prevalence of oestrosis observed in sheep and goats varied dramatically across regions and countries [51, 52]. This variation could be due to a variable life-cycle of O. ovis, which may differ from a couple of weeks to several months in different geographical regions based on climatic and environmental conditions. An earlier study reported that flies became active when the environmental temperatures were above 12–18 °C and larvae showed quick movement and dynamic foraging behaviour at 19–22 °C [87]; this is in agreement with the finding of this meta-analysis. On the other hand, Cepeda-Palacios et al. [87] also reported that larvae underwent hypobiosis when the temperature was around 5 °C, and in this meta-analysis, no peak prevalence was observed under a temperature of 8 °C [38, 52]. However, it is known that O. ovis larvae are capable of adjusting their biology according to ambient environmental conditions and that range is quite large [88].

The estimated pooled prevalence indicates that oestrosis is more prevalent in sheep than in goats. These results are in agreement with other studies that reported a higher prevalence of oestrosis in sheep than in goats [40, 42, 51]. The higher prevalence in sheep could be due to more host specificity of O. ovis to sheep. Another speculation could be the moistness of muzzle. It is known that goats consume less water than sheep; therefore, their noses are usually less humid than in sheep. This higher humidity may help the larvae to survive more easily in sheep [89]. Additionally, sheep and goats also differ in respect to immune response and may have different responsiveness to an adult fly strike. The host-related odour difference between sheep and goats may also play a significant role in oestrosis prevalence [90].

The estimated pooled prevalence of oestrosis was higher in adults than in young animals. This finding agrees with the results of many studies [21, 29, 34, 54, 79], but not with several others [30, 59, 60]. A possible reason for the high prevalence in adult animals may be that adult animals are more attractive to the female flies and the surface area in the nasal orifice of adult animals are much broader than of young animals. Furthermore, the respiration rates of adult animals are slower than of young that may offer assistance the female fly to oviposit and to larvae to crawl into the nasal sinuses. Moreover, a young animal may have maternally derived antibodies against oestrosis [91]. Conversely, several reports observed that age of the animal (> 13 weeks) positively influenced the immune response (humoral or cellular) development against O. ovis in sheep, which tends to vary with infestation load and other factors [92–94]. Likewise, another study reported that lamb could have a higher infestation and larval burden and are significantly responsible for maintaining oestrosis due to less developed immune competency [95].

Oestrosis was higher in female animals than in male animals based on estimated pooled prevalence. This is plausibly due to an increased density of females to males in flocks or to the physiological differences between males and females or a particular habit of female animals which facilitates their infestation by O. ovis larvae [34]. Conversely, the effect of sex on the prevalence of oestrosis was not significant in one study [31], and a higher prevalence in males was observed in another study [34].

The difference in prevalence considering the origin of the sample, the method of detection and the duration of the study was also significant. Prevalence was higher in farm-based studies compared to abattoirs; this may be due to the method of detection, as farm-based studies mostly rely upon serology [7] and there is a high chance that the fly can attack many animals of a flock in a particular farm in an endemic area. On the other hand, animals slaughtered in an abattoir usually come from different regions and different farms; therefore, the pooled prevalence can be lower. However, year-round surveillance can give an actual prevalence estimate.

Funnel plot asymmetry reveals strong evidence of the presence of publications bias. However, there are many other reasons for funnel plot asymmetry like true heterogeneity, location, data irregularity and artefacts, or even by chance [28].

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, no report on oestrosis of sheep and goats was found in the continent of Australia within the range of this meta-analysis. Thus a reflection of the prevalence from these regions could not be obtained. Moreover, only four studies from South America and one study from North America were obtained, and all five articles reported the prevalence of sheep oestrosis, so the prevalence of goat oestrosis could not be estimated. Secondly, most of the studies were conducted in head samples obtained directly from abattoirs, so in some cases it could be difficult to determine the actual age and sex of the animals and exact prevalence estimation. Thirdly, non-English articles, unpublished articles, case reports and results of experimental trials were not included in this meta-analysis. Fourthly, due to unavailability of data regarding age, sex and peak prevalence season in every article, all articles could not be covered for pooled prevalence estimations. Finally, the data displayed a significant heterogeneity between studies even within a particular region.

Conclusions

Results of the global meta-analysis show a very high burden of oestrosis reported in many regions, especially in northern Africa and southern Europe. The results also indicate that the disease is more prevalent in sheep than in goats. The main implication of these results is that screening tests for O. ovis and treatment should be routinely carried out in sheep and goat flocks in high disease burden regions to improve animal productivity and minimise the potential zoonotic risk to humans. Measures should also be implemented to take adequate preventive measures against O. ovis infestation. As oestrosis is found more prevalently in adult animals, vaccine development and immunisation at the young stage of life may prevent the disease. Moreover, reports on the prevalence of oestrosis in sheep and goats are still not available from many regions; therefore, epidemiological surveillance is needed for estimating the disease burden and for controlling the disease. Additionally, factors that contribute to the prevalence estimate should be handled appropriately in any survey to estimate the true prevalence of oestrosis.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1. PRISMA 2009 checklist.

Additional file 2: Text S1. Quality assessment checklist of individual studies. Table S2. Quality score of studies included in the meta-analysis. Figure S1. Frequency distribution of eligible studies characteristics.

Additional file 3: Text S2. List of the articles excluded in the present meta-analysis with justification.

Additional file 4: Text S3. List of the articles included in the present meta-analysis.

Additional file 5: Figure S2. Sub-group analysis of ambient environmental temperature at which the peak prevalence of oestrosis was found in sheep and goats in different continents and countries of the world.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Drs Maurice Zeegers (Maastricht University) for his courses on meta-analysis. The author would like to acknowledge the Dixson Library of the University of New England, Australia which enabled access to literature databases.

Authors’ contributions

MA conceived the idea, designed, analysed, wrote and revised the manuscript. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Important datasets that support the conclusions of this article are included within the article and in additional files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Horak I. Parasites of domestic and wild animals in South Africa. XLVI. Oestrid fly larvae of sheep, goats, springbok and black wildebeest in the Eastern Cape Province. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2005;72:315–320. doi: 10.4102/ojvr.v72i4.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Francesconi F, Lupi O. Myiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:79–105. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00010-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scala A, Paz-Silva A, Suárez J, López C, Díaz P, Diez-Banos P, et al. Chronobiology of Oestrus ovis (Diptera: Oestridae) in Sardinia, Italy: guidelines to chemoprophylaxis. J Med Entomol. 2002;39:652–657. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-39.4.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dorchies P, Duranton C, Jacquiet P. Pathophysiology of Oestrus ovis infection in sheep and goats: a review. Vet Rec. 1998;142:487–489. doi: 10.1136/vr.142.18.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacquiet P, Ngoc TTT, Nouvel X, Prevot F, Grisez C, Yacob HT, et al. Regulation of Oestrus ovis (Diptera: Oestridae) populations in previously exposed and naïve sheep. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2005;105:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2004.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angulo-Valadez C, Ascencio F, Jacquiet P, Dorchies P, Cepeda-Palacios R. Sheep and goat immune responses to nose bot infestation: a review. Med Vet Entomol. 2011;25:117–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2010.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papadopoulos E, Prevot F, Diakou A, Dorchies P. Comparison of infection rates of Oestrus ovis between sheep and goats kept in mixed flocks. Vet Parasitol. 2006;138:382–385. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maxie G. Jubb, Kennedy & Palmerʼs pathology of domestic animals-E-book. Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahaduzzaman M, Islam M, Akter S, Uddin M, Sharif S, Mannan A. Asphyxial death by Oestrus ovis in a pneumonic goat. J Adv Parasitol. 2015;2:48–51. doi: 10.14737/journal.jap/2015/2.3.48.51. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sotiraki S, Hall MJ. A review of comparative aspects of myiasis in goats and sheep in Europe. Small Ruminant Res. 2012;103:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2011.10.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacquiet P, Dorchies P. Towards a lower prevalence of Oestrus ovis infections in sheep in a temperate climate (south west France) Vet Res. 2002;33:449–453. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2002031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorchies P, Alzieu J, Cadiergues M. Comparative curative and preventive efficacies of ivermectin and closantel on Oestrus ovis (Linné 1758) in naturally infected sheep. Vet Parasitol. 1997;72:179–184. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(97)00052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao S, Radhakrishnasetty N, Chadalavada H, Hiremath C. External ophthalmomyiasis by Oestrus ovis: a case report from Davangere. J Lab Phys. 2018;10:116. doi: 10.4103/JLP.JLP_18_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basmaciyan L, Gabrielle P-H, Valot S, Sautour M, Buisson J-C, Creuzot-Garcher C, et al. Oestrus ovis external ophtalmomyiasis: a case report in Burgundy France. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018;18:335. doi: 10.1186/s12886-018-1003-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernhardt V, Finkelmeier F, Verhoff MA, Amendt J. Myiasis in humans—a global case report evaluation and literature analysis. Parasitol Res. 2019;118:389–397. doi: 10.1007/s00436-018-6145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunbar J, Cooper B, Hodgetts T, Yskandar H, van Thiel P, Whelan S, et al. An outbreak of human external ophthalmomyiasis due to Oestrus ovis in southern Afghanistan. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:e124–e126. doi: 10.1086/588046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzzoni-Blatger J, Villeneuve L, Morassin B, Chevallier J. A case of external human ophthalmomyiasis by Oestrus ovis in Toulouse (France) J Fr Opthalmol. 2000;23:1020–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gregory AR, Schatz S, Laubach H. Ophthalmomyiasis caused by the sheep bot fly Oestrus ovis in northern Iraq. Optom Vis Sci. 2004;81:586–590. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000141793.10845.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alahmed A. Seasonal infestation of Oestrus ovis larvae in sheep heads in central region of Saudi Arabia. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2000;30:895–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benakhla A, Sedraoui S, Benouareth D, Cabaret J, Boulard C. Epidemiology of sheep infection by Oestrus ovis in Algeria. Parasite. 2004;11:235–238. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2004112235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Attindehou S, Salifou S, Gbangboche A, Abiola F. Prevalence of the small ruminant’s oestrosis in Benin. J Anim Vet Adv. 2012;11:1647–1650. doi: 10.3923/javaa.2012.1647.1650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amin A, Morsy T, Shoukry A, Mazyad S. Oestrid head maggots in slaughtered sheep in Cairo abattoir. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1997;27:855–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papadopoulos E, Prevot F, Jacquiet P, Duranton C, Bergeaud J, Kalaitzakis E, et al. Seasonal variation of Oestrus ovis-specific antibodies in sheep and goats mixed flocks in Greece. Vet Parasitol. 2001;95:73–77. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(00)00414-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Islam MZ, Musekiwa A, Islam K, Ahmed S, Chowdhury S, Ahad A, et al. Regional variation in the prevalence of E. coli O157 in cattle: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chidumayo NN. Epidemiology of canine gastrointestinal helminths in sub-Saharan Africa. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:100. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-2688-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:934–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osman M: Epidemiological studies on Oestrus ovis infection, in sheep and goats in Shalatin area, Red Sea Governorate, Egypt. In: Proceedings of the 3rd scientific conference of animal wealth research in the Middle East and North Africa, Foreign agricultural relations (FAR), Egypt, 29 November-1 December 2010: Massive conferences and trade fairs; 25–40.

- 30.Alem F, Kumsa B, Degefu H. Oestrus ovis larval myiasis among sheep and goats in Central Oromia, Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2010;42:697–703. doi: 10.1007/s11250-009-9477-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gebremedhin EZ. Prevalence of ovine and caprine oestrosis in Ambo, Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2011;43:265–270. doi: 10.1007/s11250-010-9687-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yilma J, Genet A. Epidemiology of the sheep nasal bot, Oestrus ovis (Diptera: Oestridae), in Central Ethiopia. Rev Med Vet. 2000;151:143–150. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gabaj M, Beesley W, Awan M. Oestrus ovis myiasis in Libyan sheep and goats. Trop Anim Health Prod. 1993;25:65–68. doi: 10.1007/BF02236505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Negm-Eldin MM, Elmadawy RS, Hanan GM. Oestrus ovis larval infestation among sheep and goats of Green Mountain areas in Libya. J Adv Vet Anim Res. 2015;2:382–387. doi: 10.5455/javar.2015.b105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jagannath M, Cozab N, Rahman SA, Honnappa T. Serodiagnosis of Oestrus ovis infestation in sheep and goats. Indian J Anim Sci. 1989;59:1220–1224. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pathak K. Incidence of Oestrus ovis in sheep and goats in Rajasthan state of India. Indian J Anim Sci. 1992;62:50–53. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dehghani R, Sedaghat MM, Esmaeli N, Ghasemi A. Myiasis among slaughtered animals in Kashan, Iran: descriptive a veterinary entomological problem in the tropics. Iran J Vet Sci Technol. 2012;4:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shoorijeh JS, Tamadon A, Negahban S, Behzadi M, Biglari S. Seasonal infection rates of Oestrus ovis. Online J Vet Res. 2010;14:302–310. [Google Scholar]

- 39.İpek DNS, Altan S. Use of semi-nested PCR and rhinoscopy for the diagnosis of oestrosis. Small Ruminant Res. 2017;150:76–79. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2017.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dorchies P, Bergeaud J, Tabouret G, Duranton C, Prevot F, Jacquiet P. Prevalence and larval burden of Oestrus ovis (Linne 1761) in sheep and goats in northern Mediterranean region of France. Vet Parasitol. 2000;88:269–273. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(99)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Papadopoulos E, Chaligiannis I, Morgan ER. Epidemiology of Oestrus ovis L. (Diptera: Oestridae) larvae in sheep and goats in Greece. Small Ruminant Res. 2010;89:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2009.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daniela M. The prevalence of wormy sinusitis in goats from the west side of our country. Sci Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2008;41:762–764. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramadan MY, Khater HF, Omer SF, Rahman AA. Epidemiology of Oestrus ovis infesting Egyptian sheep. In: XX International congress of Mediterranean federation of health and production of ruminants, Egypt, 19–22 February; 2013.

- 44.Bekele T, Mukasa-Mugerwa E. Oestrus ovis infection in Ethiopian highland sheep. Vet Res Commun. 1994;18:439–442. doi: 10.1007/BF01839420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pandey V, Ouhelli H. Epidemiology of Oestrus ovis infection of sheep in Morocco. Trop Anim Health Prod. 1984;16:246–252. doi: 10.1007/BF02265332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oniye S, Adebote D, Ahunanya C. Observations on Oestrus ovis L. (Diptera: Oestridae) myiasis in the nasal cavities and sinuses of the domestic sheep (Ovis aries) in Zaria, Northern Nigeria. Int J Zool Res. 2006;2:178–185. doi: 10.3923/ijzr.2006.178.185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Horak IG. Parasites of domestic and wild animals in South Africa. I. Oestrus ovis in sheep. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1977;44:55–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pandey V. Epidemiology of Oestrus ovis infection of sheep in the highveld of Zimbabwe. Vet Parasitol. 1989;31:275–280. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(89)90077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saleem T, Katoch R, Yadav A, Mir IA, Godara R, Ahamed I. Prevalence of ovine oestrosis in plain and kandi areas of Jammu, North India. Int J Sci Environ Technol. 2017;6:1117–1122. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharma MGA, Mahajan C, Ingle S. Incidence of Oestrus ovis in sheep in Udaipur region of Rajasthan. Vet Pract. 2012;13:260–261. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dhishonin S, Babu RN, Ramani R, Porteen K, Rao VA, Abraham RJ. A survey of disease conditions in sheep and goats slaughtered at Coimbatore District slaughter house, Tamil Nadu, India. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2017;6:3692–3699. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2017.610.433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shoorijeh SJ, Negahban S, Tamadon A, Behzadi MA. Prevalence and intensity of Oestrus ovis in sheep of Shiraz, southern Iran. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2009;41:1259–1262. doi: 10.1007/s11250-009-9309-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tavassoli M, Tajik H, Malekifard F, Soleimanzadeh A, Mardani K. Seasonal infestation of Oestrus ovis larvae in slaughtered sheep in Urmia, Iran. Iran Vet J. 2012;7:98–104. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Al-Ubeidi N, ALani AJ, Al-kennany E. Detection of nasal bot fly larvae in slaughtered sheep of Ninevah governorate, Iraq. Basra J Vet Res. 2017;16:240–247. doi: 10.33762/bvetr.2017.143547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abo-Shehada MN, Arab B, Mekbel R, Williams D, Torgerson P. Age and seasonal variations in the prevalence of Oestrus ovis larvae among sheep in northern Jordan. Prev Vet Med. 2000;47:205–212. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5877(00)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Othman RA. Seasonal prevalence of Oestrus ovis in Awassi sheep of north of West Bank (Palestine) IUG J Nat Stud. 2015;17:83–88. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alikhan M, Al-Ghamdi K, Al-Zahrani FS, Khater EI, Allam AM. Prevalence and salient morphological features of myiasis causing Dipteran flies in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Biosci Biotechnol Res Asia. 2018;15:101–109. doi: 10.13005/bbra/2612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hanan BA. Seasonal prevalence of Oestrus ovis L. (Diptera: Oestridae) larvae in infested sheep in Jazan Region, Saudi Arabia. J Parasitol Vector Biol. 2013;5:66–71. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arslan M, Kara M, Gicik Y. Epidemiology of Oestrus ovis infestations in sheep in Kars province of north-eastern Turkey. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2009;41:299. doi: 10.1007/s11250-008-9190-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karatepe B, Karatepe M, Güler S. Epidemiology of Oestrus ovis L. infestation in sheep in Nigde province, Turkey. Revue Med Vet. 2014;165:225–230. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Özdal N, Tanritanir P, Ilhan F, Değer S. The prevalence of ovine oestrosis (Oestrus ovis Linnaeus, 1761, Diptera: Oestridae) and risk factors in eastern Turkey. Veterinarski Arhiv. 2016;86:323–333. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uslu U, Dik B. Prevalence and intensity of Oestrus ovis in Akkaraman sheep in the Konya region of Turkey. Med Vet Entomol. 2006;20:347–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2006.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yilma J, Dorchies P. Epidemiology of Oestrus ovis in southwest France. Vet Parasitol. 1991;40:315–323. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(91)90111-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bauer C, Steng G, Prevot F, Dorchies P. Seroprevalence of Oestrus ovis infection in sheep in southwestern Germany. Vet Parasitol. 2002;110:137–143. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(02)00317-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Caracappa S, Rilli S, Zanghi P, Di Marco V, Dorchies P. Epidemiology of ovine oestrosis (Oestrus ovis Linne 1761, Diptera: oestridae) in Sicily. Vet Parasitol. 2000;92:233–237. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(00)00317-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Scala A, Solinas G, Citterio C, Kramer L, Genchi C. Sheep oestrosis (Oestrus ovis Linné 1761, Diptera: Oestridae) in Sardinia, Italy. Vet Parasitol. 2001;102:133–141. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(01)00515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cozma V, Cernea C, Achelăriţei D, Losson B. The pathology of Oestrus ovis and an investigation on the use of a skin hypersensitivity test for the diagnosis of sheep oestrosis. Sci Parasitol. 2010;11:35e7. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alcaide M, Reina D, Frontera E, Navarrete I. Analysis of larval antigens of Oestrus ovis for the diagnosis of oestrosis by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Med Vet Entomol. 2005;19:151–157. doi: 10.1111/j.0269-283X.2005.00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Alcaide M, Reina D, Sánchez-López J, Frontera E, Navarrete I. Seroprevalence of Oestrus ovis (Diptera, Oestridae) infestation and associated risk factors in ovine livestock from southwestern Spain. J Med Entomol. 2005;42:327–331. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2005)042[0327:SOOODO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gracia MJ, Lucientes J, Peribáñez MA, Castillo JA, Calvete C, Ferrer LM. Epidemiology of Oestrus ovis infection of sheep in northeast Spain (mid-Ebro Valley) Trop Anim Health Prod. 2010;42:811–813. doi: 10.1007/s11250-009-9503-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gracia M, Lucientes J, Peribáñez M, Calvete C, Ferrer L, Castillo J. Kinetics of Oestrus ovis infection and activity of adult flies. Parasite. 2006;13:311–313. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2006134311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Paredes-Esquivel C, Monerris M, Martķ T, Borrąs D, Miranda M. High prevalence of myiasis by Oestrus ovis in the Balearic Islands. Parasite. 2009;16:323–324. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2009164323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paredes-Esquivel C, del Rio R, Monerris M, Borràs D, Laglera LM, Miranda MÁ. The influence of sheep age group on the seasonal prevalence of oestrosis in the island of Majorca. Vet Parasitol. 2012;186:538–541. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Carvalho RS, Ruivo MA, Colli MHA, Pereira V, Martinez AC, Mazzucatto BC, et al. Occurrences of Oestrus ovis parasitism in necropsied sheep in the Umuarama microregion, Paraná, Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2015;24:370–374. doi: 10.1590/S1984-29612015044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Silva BF, Machado GP, Izidoro TB, Amarante AF. Prevalence of Oestrus ovis (Diptera: Oestridae) in sheep from the São Paulo Central region, Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2013;22:18–21. doi: 10.1590/S1984-29612013005000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Silva BF, Bassetto CC, Amarante AFT. Epidemiology of Oestrus ovis (Diptera: Oestridae) in sheep in Botucatu, State of São Paulo. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2012;21:386–390. doi: 10.1590/S1984-29612012000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hidalgo A, Palma H, Oberg C, Fonseca-Salamanca F. Oestrus ovis infection of grazing sheep during summer in southern Chile. Pesqui Vet Bras. 2015;35:497–500. doi: 10.1590/S0100-736X2015000600002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Murguía M, Rodrıguez J, Torres F, Segura J. Detection of Oestrus ovis and associated risk factors in sheep from the central region of Yucatan, Mexico. Vet Parasitol. 2000;88:73–78. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(99)00204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Biu AA, Nwosu CO. Incidence of Oestrus ovis infestation in Borno-White Sahel goats in the semi-arid zone of Nigeria. Vet Res. 1999;30:109–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Horak IG, Butt M. Parasites of domestic and wild animals in South Africa II Oestrus ovis in goats. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1977;44:55–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rahman M, Karim M. Incidence of Oestrus ovis in sheep and goats. Indian J Anim Sci. 1989;59:1216–1219. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Huq M. Incidence of sheep nasal bot (Oestrus ovis linn. Diptera: Oestridae) in Black Bengal goats of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Vet J. 1983;5:34–36. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jumde P, Dixit M. Survey of Oesrtus ovis infestation in goats: an abatoir study. Indian J Field Vet. 2012;7:44–46. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shoorijeh JS, Tamadon A, Negahban S, Behzadi M. Prevalence of Oestrus ovis in goats of Shiraz, southern Iran. Veterinarski Arhiv. 2011;81:43–49. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Abo-Shehada MN, Batainah T, Abuharfeil N, Torgerson P. Oestrus ovis larval myiasis among goats in northern Jordan. Prev Vet Med. 2003;59:13–19. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5877(03)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Alcaide M, Reina D, Frontera E, Navarrete I. Epidemiology of Oestrus ovis (Linnaeus, 1761) infestation in goats in Spain. Vet Parasitol. 2005;130:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cepeda-Palacios R, Angulo Valadez C, Scholl J, Ramírez-Orduña R, Jacquiet P, Dorchies P. Ecobiology of the sheep nose bot fly (Oestrus ovis L.): a review. Rev Méd Vét. 2011;162:503–507. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cobbett N, Mitchell W. Further Observations on the life cycle and incidence of the sheep bot, Oestrus ovis, in New Mexico and Texas. Am J Vet Res. 1941;2:358–361. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cepeda-Palacios R, Scholl P. Factors affecting the larvipositional activity of Oestrus ovis gravid females (Diptera: Oestridae) Vet Parasitol. 2000;91:93–105. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(00)00265-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Poddighe S, Dekker T, Scala A, Angioy AM. Olfaction in the female sheep botfly. Naturwissenschaften. 2010;97:827–835. doi: 10.1007/s00114-010-0700-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Silva BF, Bassetto C, Amarante AF. Immune responses in sheep naturally infected with Oestrus ovis (Diptera: Oestridae) and gastrointestinal nematodes. Vet Parasitol. 2012;190:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Suárez J, Scala A, Romero J, Paz-Silva A, Pedreira J, Arias M, et al. Analysis of the humoral immune response to Oestrus ovis in ovine. Vet Parasitol. 2005;134:153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Angulo-Valadez C, Scala A, Grisez C, Prevot F, Bergeaud J-P, Carta A, et al. Specific IgG antibody responses in Oestrus ovis L. (Diptera: Oestridae) infected sheep: associations with intensity of infection and larval development. Vet Parasitol. 2008;155:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Silva BFD, Bassetto CC, Amarante AFTD. Immune humoral response of young lambs naturally infested by Oestrus ovis (Diptera: Oestridae) Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2018;27:295–300. doi: 10.1590/S1984-296120180045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rogers C, Knapp F. Bionomics of the sheep bot fly, Oestrus ovis. Environ Entomol. 1973;2:11–23. doi: 10.1093/ee/2.1.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. PRISMA 2009 checklist.

Additional file 2: Text S1. Quality assessment checklist of individual studies. Table S2. Quality score of studies included in the meta-analysis. Figure S1. Frequency distribution of eligible studies characteristics.

Additional file 3: Text S2. List of the articles excluded in the present meta-analysis with justification.

Additional file 4: Text S3. List of the articles included in the present meta-analysis.

Additional file 5: Figure S2. Sub-group analysis of ambient environmental temperature at which the peak prevalence of oestrosis was found in sheep and goats in different continents and countries of the world.

Data Availability Statement

Important datasets that support the conclusions of this article are included within the article and in additional files.