The issue of accessible veterinary care has been growing in the veterinary professional discourse. Currently, there is considerable interest in addressing the barriers to accessible veterinary care. Broad categories of barriers to accessible veterinary care include socioeconomic, geographic, and knowledge-based barriers. These are not mutually exclusive of one another and contribute to the complexity of accessible veterinary care. The financial or socioeconomic barriers to care often create the most tension in daily veterinary practice and within the broader profession, while geographic barriers pose both logistical and sociocultural challenges. Barriers to accessible care impact not only animal welfare, but also the experiences of those who care for the animals, animal owners and veterinarians alike. It should be noted that the veterinary profession, animal welfare agencies, and animal health industries have been highly successful in reducing knowledge-based barriers to care through active public engagement, communication, and education on issues such as preventive medicine, population control (spay/neuter), and care for cats. The purpose of this paper is not to provide an exhaustive examination of this challenging issue, but rather to engage with veterinary professionals in an open dialogue on multi-level barriers to care in order to further our understanding.

Research on the issues of accessible veterinary care is being conducted by several groups including the Access to Veterinary Care Coalition (AVCC) at The University of Tennessee Knoxville (1), Shelter and Community Medicine at Tufts University (2,3), the Access to Care Initiative of the American Veterinary Medical Association (4), and the Strategy and Research Department of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (5). In terms of barriers to accessible care, the recent AVCC report identified challenges to providing care from perspectives of both veterinarians and animal owners. Among veterinarians, factors impacting the provision of accessible care include personal finances (e.g., student debt), concerns about standard of care, workplace policies, and devaluing professional services. This report also identified how veterinarians’ attitudes on pet ownership may impact the provision of accessible care: “the majority of respondents do not think everyone is entitled to own a pet…However, veterinarians in urban areas were more likely to believe that everyone is entitled to a pet and that society bears some responsibility to help care for all pets” (1). Among pet owners, socioeconomic and financial factors are not surprisingly, significant barriers to accessing veterinary care along with transportation challenges, not having appropriate equipment (e.g., carrier), geographic barriers, and not knowing where to get care (1).

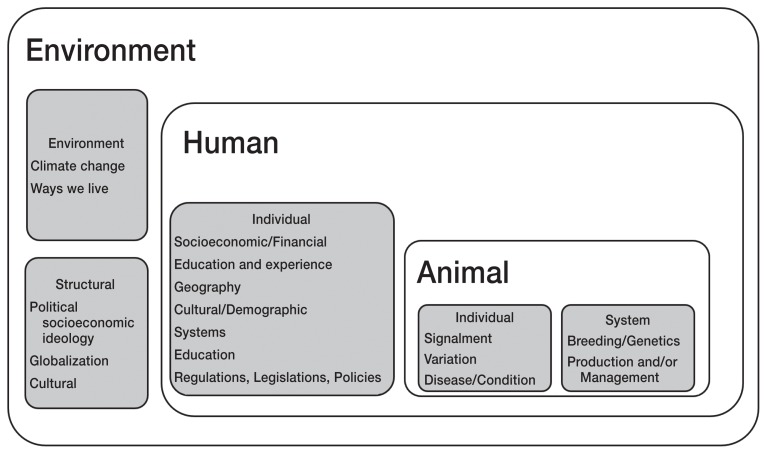

As noted earlier, the issue of accessible veterinary care is complex. Therefore, in order to examine this issue in a structured approach, a One Health framework will be used. Adopting a One Health model ensures that other sectors and stakeholders are considered, as well as the interactions between sectors. Additionally, it supports the examination of complex issues from multiple levels, including individual, institutional and systemic, and structural levels. For the purposes of this paper in exploring the barriers to accessible care, the human sector of the One Health model will include both individual and institutional or systemic barriers, whereas structural barriers and influences will be considered within the broader environment sector. A nested One Health model was developed by the author in order to frame the rest of the discussion (Figure 1). Similar to social determinants of health frameworks (6), a nested model appropriately describes how larger structures influence both systems and individual experiences in the context of accessible care.

Figure 1.

Nested One Health model to explore barriers to accessible veterinary care.

Naturally, the sector that has been most explored in terms of accessible care is the human sector. As mentioned previously, the stakeholders providing individual care include both animal owners and veterinarians. Socioeconomic and/or financial factors are obvious barriers for animal owners to access veterinary care in terms of available disposable income and affordability. However, financial factors may also be barriers for veterinarians in providing care. For example, financial factors for veterinarians including operational costs and remuneration models based on production may influence provision of care. Education level influences access to care for animal owners both directly through an awareness of the health needs of animals and indirectly through the effect of education level on employability, socioeconomic, and financial status. Similarly, for veterinarians, the cost of education creates significant debt load and when remuneration is tied to production may create further financial barriers. Geographical factors for animal owners may be tied to socioeconomic status for those living in impoverished areas, but also for rural or remote areas which may be “care deserts” where there are few to no veterinary services available. Such geographical issues impact care provision for veterinarians as well, creating logistical, operational, and financial challenges in serving large geographical areas with smaller populations, as well as challenges in attracting veterinarians to rural and remote areas. The issue of serving rural and remote populations is not unique to veterinary medicine and is tied to several larger systems and structures.

The role of demographics and culture on barriers to care further adds to the complexity of this issue. Among animal owners, cultural roles of animals, expectations of care, and individual experiences contribute to accessing veterinary care. For example, self-sufficiency, stoicism, and trust are cultural issues that have been identified as barriers to accessing care among rural Canadian farmers (7). Among veterinarians, similar factors of roles of animals, expectation of care, and individual experience impact where, how, when, and to whom care is provided. As mentioned, attitudes and perceptions on the right to pet ownership, the value of veterinary care, as well as risk and liability, and appropriate standards of care contribute to the provision of care.

Systems within the human sector include human health systems, education, and regulations, legislations, and policies. The human health system is relevant to the discussion on accessible veterinary care, as there are still considerable barriers to accessible and equitable human health care even within a Canadian universal health care system. Therefore, it may be unreasonable to expect that equitable animal health care access is achieved before human health care access. In the One Health model, human health is tied to animal health, and therefore by extension it could be argued that where there is inequitable access to human health care there will be inequitable access to animal health care. Education is also identified as a system within the human sector as veterinary education influences our approaches to the practice of medicine including standards of care. Veterinary regulations and legislations that influence standards of practice and therefore liability, as well as workplace rules and policies further impact the provision of care.

In this One Health model the animal sector is nested within the human sector as humans are ultimately responsible for their care and management. With respect to accessible care, animal-based factors influence the amount and kind of care required, including species, breed, age, and reproductive status. Individual variation within any given population further impacts care, as well as the condition of the animal and/or disease process. Systems within the animal sector include the human manipulation of genetics through breeding, as the impacts of the systematic selection (and public demand) for unhealthy traits in animals on accessible veterinary care cannot be ignored (8). Furthermore, human-derived intensive animal (food) management and production systems influence all three One Health sectors (9).

Lastly, we will discuss the larger and broader environmental and structural factors that influence accessibility of veterinary care. Throughout the previous discussions, the web of interconnections between both factors and sectors has been explored; however, large structural factors are often ignored in discussions on accessible care. Much like the social determinants of human health, broad socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental conditions in which we live and work have a powerful influence on both human and animal health (10). Environmental conditions including climate change, urbanization, and globalization impact the daily lives and experiences of individuals, families, communities, and the animals with which we live and work. For example, the effects of climate change disproportionately affect the poor and vulnerable, humans and animals alike. Environmental inequalities and injustices include speciesism via wildlife extinction and endangerment but are also experienced in urban populations. One well-known example is hurricane Katrina, in which environmental injustice and human (and animal) neglect were shown to be tied to race, education, and class (11) and further prompted the 2006 US Pet Evacuation and Transport Standards (PETS) Act (12). This environmental disaster highlighted the impacts of structural inequalities on both humans and animals.

It is in this way that political socioeconomic factors are important to consider when discussing the issues of accessible veterinary care, as these large factors are also tied to deeper issues of race, class, and gender inequalities. As veterinary care is fee-for-service, to exclude discussion of these issues would be to ignore the reality of people’s lived experiences in current political socioeconomic times. As previously stated, the issue of accessible care is complex, and while exploring these barriers through lenses of One Health and structural influences may uncomfortably increase its complexity, our social discourse and actions must include ways to acknowledge and address these multi-level barriers to accessible care.

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Access to Veterinary Care [page on the Internet] The University of Tennessee; Knoxville: 2018. [Last accessed June 18, 2019]. Available from: http://avcc.utk.edu/avcc-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavallee E, Mueller MK, McCobb E. A systematic review of the literature addressing veterinary care for underserved communities. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2017;20:381–394. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2017.1337515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benka VA, McCobb E. Characteristics of cats sterilized through a subsidized, reduced-cost spay-neuter program in Massachusetts and of owners who had cats sterilized through this program. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2016;249:490–498. doi: 10.2460/javma.249.5.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Houlihan K. Access to Care Initiative of the American Veterinary Medical Association. Apr 11, 2019. E-mail to Michelle Lem (michell.lem@vetoutreach.org) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slater M. Strategy and Research Department of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Apr 9, 2019. E-mail to Michelle Lem (michell.lem@vetoutreach.org) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mikkonen J, Raphael D. Social determinants of health: The Canadian facts. York University, School of Health Policy and Management; 2010. [Last accessed June 18, 2019]. Available from: http://thecanadianfacts.org/The_Canadian_Facts.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wasson E, Wieman A. Mental health during environmental crisis and mass incident disasters. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2018;34:375–388. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valliant S, Fagan JM. Healthcare Costs Associated with Specific Dog Breeds. Rutgers University; 2014. [Last accessed June 18, 2019]. Available from: https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/48043/PDF/1/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMichael AJ, Powles JW, Butler CD, Uauy R. Food, livestock production, energy, climate change, and health. Lancet. 2007;370:1253–1263. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Card C, Epp T, Lem M. Exploring the social determinants of animal health. J Vet Med Ed. 2018;4:1–11. doi: 10.3138/jvme.0317-047r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adeola FO, Picou JS. Hurricane Katrina-linked environmental injustice: Race, class, and place differentials in attitudes. Disasters. 2017;41:228–257. doi: 10.1111/disa.12204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.PETS Act (FAQ) [page on the Internet] The American Veterinary Medical Association; c2019. [Last accessed June 18, 2019]. Available from: https://www.avma.org/KB/Resources/Reference/disaster/Pages/PETS-Act-FAQ.aspx. [Google Scholar]