Wayne Gretzky once explained how he became a hockey player of genius: “I skate to where the puck is going to be, not where it has been.” Since the Affordable Care Act (ACA) enacted the hospital readmissions reduction program, hospitals have been ever more focused on playing to the puck to avoid financial penalties for high rates of early readmission. This Viewpoint examines the early readmission reduction program as an example of similar initiatives by CMS and discusses the pros and cons of the increasing use of financial penalties for changing the behavior of hospitals.

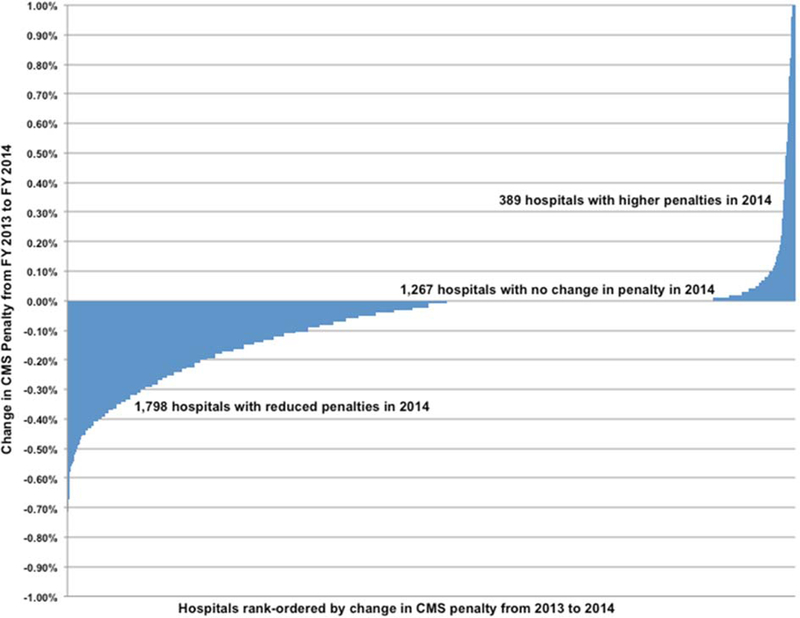

Using financial incentives to change practice is a tried-and-true CMS strategy. The agency promulgated the diagnosis-related group (DRG) system to encourage hospitals to reduce hospital bed-days, and hospital length of stay plummeted. More recently CMS reduced payments for care for hospital-acquired infections. The state of Maryland responded aggressively and reduced its hospital-acquired infection rate by 15%.1 In October 2012, the ACA has enacted a first wave of penalties for high rates of early readmission to the hospital, imposing penalties on 61 percent of hospitals with payment reductions averaging 0.24% and ranging up to 1 percent of all CMS-based DRG reimbursements (Figure).2 A new round of more severe Medicare reimbursement penalties rolled out on October 1, 2013; the maximum penalty is 2 percent of DRG reimbursements for 2014. Recent CMS projections for 2014 show lower penalties for 52% of the hospitals.3 However, only 81 hospitals are likely to avoid penalties altogether.

Figure. Change in Payment Penalty from 2013 to 2014 by US Hospital.

Data are provided by the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program ‐ Supplemental Data (FY 2013 and 2014 IPPS Proposed Rule).3 The change in penalty is calculated by the difference between fiscal years 2013 and 2014. A negative value representing a reduction in the percent of CMS reimbursement penalty. No change, a value of 0.00 percent represents hospitals without a change in penalty from 2013 to 2014. A positive change represents a more severe penalty or first‐time penalty such as a hospital the maximum penalty in 2013 of 1.00 percent to 2.00 percent in 2014.

The penalties worked. More than half of US hospitals reduced their early readmission rate in less than one year.3 Apparently, many hospitals have allocated resources toward preventing readmissions, including dedicating staff to manage transitional care and follow-up, increasing at-home monitoring, and employing health care coaches to empower patients to take responsibility for their own care.

While this response shows that hospitals can improve the rate of early readmissions, the focus on this outcome may have unintended consequences. Reallocating resources to avoid a specific penalty may compromise quality of care, safety, and patient satisfaction for other clinical problems. Moreover, hospitals may neglect the more important goal of improved population health and high value health care, which both CMS and accountable care organizations are trying to promote.. Hospitals must ask whether the penalty targets are important enough to justify diverting resources from broadly-based programs that could improve quality and safety for more patients.

Are early readmissions the phenomenon that needs remediation, or is it an epiphenomenon of a root cause - health care that is in excess of and not well matched to patients’ needs? Causes of early readmission include: 1) errors in hospital and transition care; and 2) a low threshold for admission and readmission; and 3) premature discharge because of pressure to vacate hospital beds to meet demand created by hospitals, physicians, and patients. All of these causes are important to address. Some hospitals are trying to provide safe and effective care while addressing excessive use of healthcare resources. Using the example of early readmission penalties, we offer three suggestions.

First, CMS should use its power to encourage hospitals to invest in broader goals and should reward success. A small step in this direction would be to broaden the focus of the readmissions program to include admissions. Many of the behaviors that lead to unnecessary admissions also lead to readmissions. When a Medicare Quality Improvement Organization intervened in fourteen communities to improve care transitions and reduce readmissions, the per capita rate of both admissions and readmissions declined more than in comparison communities, while the rate of all cause readmissions as a proportion of hospital discharges did not change.4 The interventions were the product of hospital networks working with community representatives to improve the coordination of primary care. This unexpected result--a positive variation on the law of unintended consequences--teaches an important lesson: targeting the performance of one medical care service can change a behavior that can affect the performance of other services.

Second, hospitals should stay alert for unintended consequences from targeted interventions. Administrators should ensure that quality improvement efforts in other areas of patient care are not neglected as hospitals target interventions on the small subset of hospital services that are subject to penalties. CMS should study possible adverse consequences of lost revenue from penalties or averted readmissions. How did utilization of health care resources change? Was the net effect on quality metrics and community health status positive or negative?

Much to its credit, CMS is trying to assess one potential unintended consequence of penalizing high 30-day readmission rates: increased mortality. The agency is now measuring both utilization of healthcare resources and survival for three clinical conditions (acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia) and plans to add more conditions in 2014 and 2015. Starting in fiscal year 2014, CMS will hold a hospital accountable if its 30-day mortality rate increases while its 30-day readmission rate declines. While linking these two measures increases the pressure to make good clinical decisions, it also represents an increasingly complex, micromanaged approach that has the potential to deflect hospitals from more important goals. If CMS adds more penalties and increasingly complex measures of their effects, hospitals may be unable to target outcomes tied to CMS penalties and still work towards overall quality and safety for the population of patients they serve.

Third, CMS should begin to move beyond penalties for specific outcomes to creating broader incentives to improve overall hospital performance. CMS should focus on processes of care that drive population health, including continuity of care, care transitions, access to primary care, and, ultimately, improved population health itself. The agency has made a good start in this direction by establishing 33 measures to evaluate the performance of accountable care organizations. These measures include preventive health, care coordination and patient safety, patient and care giver experience, and high risk patient populations.5

Keeping the goal in mind

As hospitals struggle to avoid penalties, the public should reflect about the CMS strategy of penalizing failure to meet quality standards. Because hospitals respond to the threat of penalties, CMS may be tempted to expand the program of quality-linked penalties. Imagine the alarming image of a hockey rink with ten equally important pucks on the ice and players in hot pursuit of each one. Should hospitals be in constant motion, zig-zagging back and forth as they try to avoid dozens of CMS quality-linked penalties? Alternatively, CMS could use its power to direct hospitals towards the end goal of improved population health. The broad-based 33 measures of ACO performance is a good start. Holding hospitals accountable to these measures would move the puck towards the goal of healthy populations. To reach that goal, a national strategy to further motivate hospitals to do their part is needed. Financial incentives do work, an important lesson. The challenge to CMS and to hospitals is to use that knowledge wisely.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Goodman received grant support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and personal fees from Intermountain Healthcare, Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, and the Massachusetts Health Data Consortium.

References

- 1.Calikoglu S, Murray R, Feeney D. Hospital pay-for-performance programs in Maryland produced strong results, including reduced hospital-acquired conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). December 2012;31(12):2649–2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (U.S.). Report to the Congress: Medicare and the health care delivery system. Washington, D.C.: MedPAC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Section 3025, The Patient Protection and Affordability Care Act. 2009; http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcutelnpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed May 31, 2013.

- 4.Brock J, Mitchell J, Irby K, et al. Association between quality improvement for care transitions in communities and rehospitalizations among Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. January 23 2013;309(4):381–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyu H, Wick EC, Housman M, Freischlag JA, Makary MA. Patient satisfaction as a possible indicator of quality surgical care. JAMA surgery. April 2013;148(4):362–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]